| Lake Coeur d'Alene | |

|---|---|

| |

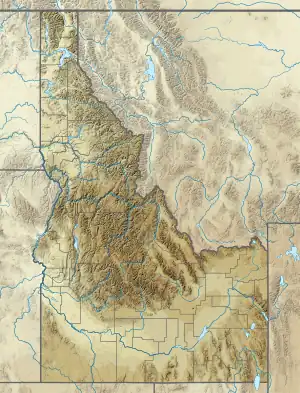

Lake Coeur d'Alene Location in Idaho  Lake Coeur d'Alene Location in the United States | |

| Location | Kootenai / Benewah counties, Idaho, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 47°30′54″N 116°49′57″W / 47.51500°N 116.83250°W |

| Type | glacial, reservoir |

| Primary inflows | Coeur d'Alene River, Saint Joe River |

| Primary outflows | Spokane River |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 25 mi (40 km) |

| Max. width | 3 mi (4.8 km) |

| Surface area | 49.8 sq mi (129 km2) |

| Average depth | 120 ft (37 m) |

| Max. depth | 220 ft (67 m) |

| Water volume | 2,260,000 acre⋅ft (2.79 km3) |

| Residence time | 0.5 years |

| Surface elevation | 2,128 ft (649 m) |

Lake Coeur d'Alene, officially Coeur d'Alene Lake ( /ˌkɔːr dəˈleɪn/ KOR də-LAYN), is a natural dam-controlled lake in North Idaho, located in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. At its northern end is the city of Coeur d'Alene. It spans 25 miles (40 km) in length and ranges from 1 to 3 miles (5 km) wide with over 109 miles (175 km) of shoreline.

The lake was named after the Coeur d'Alene people.[1]

Background

Coeur d’Alene Lake was created from floods at the end of the last Ice Age. It is a major landmark in northern Idaho and the Pacific Northwest. It is an important recreational resource for people of the community and is used for fishing, boating and swimming.[2] It is the site of the popular Coeur d'Alene Resort, and an important resource for the Schitsu’umsh (Coeur d'Alene people). Water quality of the lake is important for ensuring safe recreational use an maintaining this essential economic and ecological resource.

Geology and geography

Lake Coeur d'Alene, like other lakes surrounding the Spokane Valley and Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer, was formed by the Missoula Floods, most recently 12,000 to 15,000 years ago. The Purcell Lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet flowed south from Canada, carving the basin of present-day Lake Pend Oreille and damming the Clark Fork river. The impounded river repeatedly filled to form Glacial Lake Missoula and broke through the ice dam, resulting in massive floods that filled the Rathdrum Prairie area with sand, gravel, and boulders.[3] Large eddy bars formed downstream from bedrock obstructions, thereby damming tributary valleys and creating lakes. Lake Coeur d'Alene is fed primarily by two rivers, the Coeur d'Alene and the Saint Joe. The outflow is via the Spokane River.

The lake's elevation varies from 2,128 feet (649 m) above sea level in the summer to up to 7 feet (2.1 m) lower in the winter, controlled by the Post Falls Dam 9 miles (14 km) below the lake on the Spokane River.[4]

The lake's average summer surface temperature (June through August) is 67.5 °F (19.7 °C) .[5]

History

Lake Coeur d'Alene was long a center of culture for the Schitsu’umsh people, meaning “The Discovered People” also known as the Coeur d’Alene Tribe. The Schitsu’umsh lived in the region around the lake in Idaho as well as all the way to Western Montana and Eastern Washington. Lake Coeur d'Alene was an important source of large trout, salmon, whitefish, and water potato. The tribe has maintained its stewardship of this resource including ongoing water quality and fisheries management.[6] The Schitsu’umsh tribe has filed multiple lawsuits (1991, 2008, and 2011) to protect the quality of the water and provide funds for hazardous waste clean-up.[7]

The first-recorded European to see the area was explorer David Thompson in 1807.

Flooding as a result of the construction and operation of the Post Falls Dam significantly changed the shape and size of the lake, expanding it to combine several smaller lakes into one.[8]

The lake has been used for transporting lumber by water in Kootenai County since the timber industry started in the region. Prior to a fire in 1917, Harrison was planned as the county seat of Kootenai County, as the swiftly growing lumber town was at an opportune junction of the St. Joe and Coeur d' Alene rivers. After the fire, the mills were moved mostly to the city of Coeur d'Alene, which developed more and was designated as the county seat.

A number of Ford Model T automobiles sitting on the bottom of the lake are the result of people in the early 1900s choosing to drive in winter across the frozen lake. But they did not always judge how thick the ice was, and went through. Also, steamboats on the bottom resulted from being burned and sunk as wrecks when they were no longer of use to ferry people around the lake. Since the late 20th century, divers frequently visit these ruins on the bottom as part of their recreation. Captain Sorensen of the Amelia Wheaton, operating the Wheaton, named most of the bays and features of Lake Coeur d’Alene.

The Coeur d'Alene Tribe owns the southern third of Lake Coeur d'Alene and its submerged lands as part of its reservation, in addition to miles of the Saint Joe River and its submerged lands, all of which the United States holds in trust for the tribe. Its rights to the lake and river were established in the first executive order founding its reservation, which originally included all of the lake. In United States v. Idaho (2001),[9] the United States Supreme Court held that an 1873 executive order issued by President Ulysses S. Grant formalized ownership by the tribe.

While the court holding has not affected usage and access to Lake Coeur d'Alene, the Environmental Protection Agency has ruled that the tribe may set its own water-quality standards on its portion of Lake Coeur d'Alene.[10]

On July 5, 2020, a mid air collision between two small planes occurred over the lake. Eight people were killed in the accident.[11]

Pollution and Water Quality

Lake Coeur d'Alene has been significantly impacted by sediments containing toxic trace metals (or heavy metals, particularly lead, zinc, arsenic, and cadmium) as a result of mining and smelting activity in the Coeur d'Alene basin between the 1880s and 1960s.[12] Metal-contaminated sediments first reached the lake around 1900, and continue to be carried downstream and deposited in the lake today.[13] The Coeur d'Alene Basin, including the Coeur d'Alene River, Lake Coeur d'Alene, and portions of the Spokane River, was designated as a Superfund site in 1983 that spans 1,500 square miles (3,880 km2) and 166 miles (267 km) of the Coeur d'Alene River.[14] Most of the lake bed is covered with over 75 million metric tons of metal-contaminated sediment.[13] Most of the metals in lake are contained within the lake bed. Lake water has elevated levels of zinc, lead, and cadmium,[13] but is generally considered safe for swimming.[2] Although the lake is part of the Superfund site, it was not included in specific remediation plans. Instead, a Lake Management Plan was developed, to be implemented by the State of Idaho and the Coeur d'Alene (Schitsu’umsh) Tribe.[12][13][7]

The potential for eutrophication is an ongoing water quality concern for Lake Coeur d'Alene.[12][15] Eutrophication occurs when excess nutrients allow excess growth of algae. Eutrophication could alter chemical conditions in the lake bottom (particularly pH and oxygen concentration) so that toxic metals would be released into the lake water, potentially making the lake unsafe for current recreational use.[15] Growth of algae in the lake is limited by phosphorus, which can enter the lake through erosion and from agricultural runoff, sewage effluent and other sources.[13] High human population growth in the region has raised concerns that phosphorus inputs to the lake will increase as well.[15][13] Ironically, high zinc concentrations in the water may be reducing algae growth. As concentrations of zinc in the lake water decrease due to pollution remediation efforts in the Silver Valley, eutrophication may become more likely.[15] A recent report by the prestigious National Academy of Science did not find evidence the lake was likely to become dangerously eutrophic soon.[13] However, warmer lake water temperatures due to climate change could make eutrophication more likely, and a better understanding of sources of phosphorus in the watershed is needed.[13] The State of Idaho has recently allocated $33 million for infrastructure improvements to reduce phosphorus inputs to the lake, including improved sewage treatment facilities.[2]

Fish

Fish from Lake Coeur d'Alene were historically an important food resource for local people, and fishing is an important recreational activity on the lake. Kokanee, chinook[16] (landlocked), northern pike, largemouth and smallmouth bass are popular sportfish caught in the lake[17] These fish species were not historically native to the lake, but were introduced to improve fishing.[18] Bull trout, westslope cutthroat, and whitefish were all native to the lake, but their populations have declined and in some cases they are found only in the tributaries.[18] Kokanee, chinook, and rainbow trout were stocked by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.[7] Other fish in the lake include: black bullhead catfish, black crappie, green sunfish, largescale sucker, northern pikeminnow, pumpkinseed, tench, and yellow perch.[17] Of these species, only the largescale sucker and pikeminnow historically occurred in the lake.[19] There are Fish Consumption Advisories for the lake that recommend eating a limited number of fish from the lake per month.[17]

Recreation

.jpg.webp)

Lake Coeur d'Alene is a popular tourist site for many people during the summer, offering great beaches and scenic views. A popular seasonal activity is viewing the bald eagles as they feed on the kokanee in the lake, mainly from the Wolf Lodge Bay.[20] The North Idaho Centennial Trail, popular among cyclists, walkers, and joggers, follows along the lake's north and northeastern shore. The Trail of the Coeur d'Alenes also runs along the southern shores.

Coeur d'Alene Triathlon has been held at the lake annually since 1984, and the swimming portion of the race takes place within the lake.[21]

For a decade, the lake hosted unlimited hydroplane races for the Diamond Cup (1958–1966, 1968).[22][23][24][25][26]

Idaho State Parks and public facilities

See also

References

- ↑ Rees, John E. (1918). Idaho Chronology, Nomenclature, Bibliography. W.B. Conkey Company. p. 65.

- 1 2 3 Maldonado, Mia (June 15, 2023). "Historic mining practices continue to impact health of North Idaho's Coeur d'Alene Lake". Idaho Capital Sun. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ Breckenridge, Roy M. (May 1993). Glacial Lake Missoula and the Spokane Floods (PDF) (Report). GeoNotes. Vol. 26. Idaho Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ↑ "Post Falls Hydroelectric Development". Avista Utilities. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey. "USGS Water Data for the Nation". Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ Coeur d'Alene Tribe. "Lake Management". Coeur d'Alene Tribe. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Lake Coeur d'Alene". Spokane Riverkeeper. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- ↑ Eberlein, Jake A., Wilderness Cathedral: The Story of Idaho’s Oldest Building, Mediatrix Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0692897652

- ↑ FindLaw for Legal Professionals - Case Law, Federal and State Resources, Forms, and Code

- ↑ "EPA says Coeur d'Alene Tribe can develop water quality standards" Archived 2007-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, US Water News

- ↑ Silverman, Hollie. "Eight people are believed to be dead after two planes collided over Idaho's Coeur d'Alene Lake". CNN. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Idaho, Access. "Coeur d'Alene Lake Management". Idaho Department of Environmental Quality. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (2022). The Future of Water Quality in Coeur d'Alene Lake. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/26620. ISBN 978-0-309-69041-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Superfund Site: Bunker Hill Mining & Metallurgical Complex". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Benson, Emily (June 24, 2019). "A dangerous cocktail threatens the gem of North Idaho". High Country News. 11 (51). Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ↑ Roskelley, Fenton (June 8, 1984). "Big-time fishing at Cd'A Lake". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). p. 26.

- 1 2 3 "Coeur d'Alene Lake | Idaho Fishing Planner".

- 1 2 Plue, Erin (December 18, 2022). "OUR GEM: A brief Lake Cd'A fishtory". Coeur d'Alene/Post Falls Press. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ Wallace, Richard, L.; Zaroban, Donald, W. (2013). Native Fishes of Idaho. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Fisheries Society. ISBN 978-1-934874-35-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Turner, Dave; Hall, Mathew (December 19, 2007). "Big Bird Watching". Inlander. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ↑ "About the Coeur d'Alene Triathlon". CDA Triathlon. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ Boni, Bill (June 30, 1958). "Big Idaho race seen by 30,000". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). p. 1.

- ↑ "Hydroplane races draw many fans". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). (editorial). August 14, 1966. p. 4.

- ↑ "Diamond Cup go slated on Aug.11". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). February 15, 1968. p. 25.

- ↑ "Coeur d'Alene announces Diamond Cup cancellation". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). April 29, 1969. p. 10.

- ↑ Johnson, Bob (February 12, 1972). "Diamond Cup race may be revived". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). p. 10.

- ↑ "Mineral Ridge Scenic Area and National Recreation Trail". Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved October 30, 2020.