Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India (Portuguese: Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas e Coisas Medicinais da Índia)[lower-alpha 1] is a work of great originality published in Goa on 10 April 1563 by Garcia de Orta, a Portuguese Jewish physician and naturalist, a pioneer of tropical medicine.

Outline of the Colóquios

Garcia de Orta's work is in dialogue format. It consists of a series of 57 conversations between Garcia de Orta and an imaginary colleague, Ruano, who is visiting India and wishes to know more about its drugs, spices and other natural products. Occasional participants in the dialogue are apparently real people:

- Antonia, a slave, Garcia de Orta's research assistant

- Several unnamed slaves

- D. Jeronimo, brother of a cholera sufferer

- Dimas Bosque, a colleague who also contributes a preface to the book

- Malupa, an Indian physician

In general the drugs are considered in alphabetical order, but with exceptions. Each of the substances that comes up for discussion is dealt with fairly systematically: its identification and names in earlier texts, its source, its presence in trade, its medical and other uses. Many case histories are mentioned. The discussion of Asiatic cholera is so complete and circumstantial that it constitutes a classic of clinical description.[1]

Digressions, more or less relevant, deal with Indian politics, the significance of China, the rivalries between Portugal and Spain in the Spice Islands. There are anecdotes about elephants, cobras, and mongoose.

Contents of the Colóquios

This listing of contents gives the foliation of the first edition, which generally corresponds with that of the 1872 reprint.[2]

- Preamble. Introducing Garcia de Orta and his fictional visitor, Doctor Ruano: 1r

- Do aloes, Aloe: 2r (The juice of Aloe Socotrina, Lam.; A. vulgaris, Lam. etc.)

- Do ambre, Ambergris: 10v - Here he reports seeing pieces as big as a man, 90 palms in circumference and 18 long and one weighing 30 quintals (3000kg) near Cape Comorin. He specifically ruled out any fish or whale origins.[3]

- Do amomo, Amomum: 14v

- Do anacardo, Cashew: 16v

- Da árvore triste, Night jasmine (Nyctanthes arbortristis): 17v

- Do altiht, anjuden, assafetida e doce e odorata, anil, Asafoetida, Licorice, Storax, Indigo: 19r

- Do bangue, Cannabis: 26r

- Do benjuy, Gum benzoin: 28r

- Do ber... e dos brindões..., Bael: 32v

- Do cálamo aromático e das caceras, Sweet flag: 37v

- De duas maneiras de canfora e das carambolas, Camphor, Carambola: 41r

- De duas maneiras de cardamomo e carandas, Cardamom, Melegueta pepper, Karanda: 47r

- Da cassia fistula, Senna: 54r

- Da canella, e da cassia lignea e do cinamomo, Cinnamon, Cassia: 56v

- Do coco commum, e do das Maldivas, Coconut: 66r

- Do costo e da collerica passio, Costus, Asiatic cholera: 71v

- Da crisocola e croco indiaco ... e das curcas, Borax and Curcuma longa: 78r

- Das cubebas, Cubebs: 80r

- Da datura e dos doriões, Datura, Durian: 83r

- Do ebur o marfim e do elefante, Ivory, Elephant: 85r

- Do faufel e dos figos da India, Areca, Banana: 91r

- Do folio índico o folha da India, Malabathrum: 95r

- De duas maneiras de galanga, Galanga: 98v

- Do cravo, Cloves: 100v

- Do gengivre, Ginger: 105v

- De duas maneiras de hervas contra as camaras ... e de uma herva que não se leixa tocar sem se fazer murcha: 107v

- Da jaca, e dos jambolòes, e dos jambos e das jamgomas, Jackfruit, Jambolan, Rose apple: 111r

- Do lacre, Lac: 112v

- De linhaloes, Aloeswood: 118v

- Do pao chamado 'cate' do vulgo: 125r

- Da maça e noz, Apple, Nutmeg: 129r

- Da manná purgativa: 131v

- Das mangas, Mango: 133v

- Da margarita ou aljofar, e do chanco, donde se faz o que chamamos madreperola, Pearl, Conch, Mother of pearl: 138v

- Do mungo, melão da India, Watermelon, Urad bean: 141v

- Dos mirabolanos, Beleric, Emblic, Chebulic myrobalan: 148r

- Dos mangostões, Mangosteen: 151r

- Do negundo o sambali, Vitex negundo: 151v

- Do nimbo, Melia azedarach: 153r

- Do amfião, Opium: 153v

- Do pao da cobra: 155v

- Da pedra diamão, Diamond: 159r

- Das pedras preciosas, precious stones: 165r

- Da pedra bazar, Bezoar: 169r

- Da pimenta preta, branca e longa, e canarim, e dos pecegos, Black and white pepper, Long pepper, Peach: 171v

- Da raiz da China, China root: 177r

- Do ruibarbo, Rhubarb: 184r

- De tres maneiras de sandalo, Sandalwood, Red sanders: 185v

- Do spiquenardo, Spikenard: 189v

- Do spodio, minerals: 193r

- Do squinanto, Cymbopogon: 197r

- Dos tamarindos, Tamarind: 200r

- Do turbit, Turpeth: 203v

- Do thure... e da mirra, Frankincense, Myrrh: 213v

- Da tutia, Tutty: 215v

- Da zedoaria e do zerumbete, Zedoary, Zerumbet: 216v

- Miscellaneous observations: 219v

Appendix part 1. Do betre…, Betel (pages 37a to 37k in 1872 reprint)

Appendix part 2, with corrections to the text (pages 227r to 230r in 1872 reprint)

Authorities cited

"Don't try and frighten me with Diocorides or Galen," Garcia de Orta says to Ruano, "because I am only going to say what I know to be true."[4] Though unusually ready to differ from earlier authorities on the basis of his own observations, Garcia was well read in the classics of medicine. As a sample, the following authors (listed here in the spellings preferred by Garcia) are regularly cited in the first 80 folia of the Colóquios:

- Greek: Hipocrate, Teofrasto, Dioscoride, Galeno

- Classical Latin: Celso, Plinio

- Arabic: Rasis, Avicena, Mesue, Serapion

- Medieval Latin: Gerardo Cremonensis, Matheus Silvatico

- Later Latin: Andreas Belunensis, Andrés Laguna (aka Tordelaguna), Menardo, Mattioli (aka Matheolo Senense), Antonio Musa, Ruelio and Garcia's younger contemporary Amato Lusitano

Garcia also occasionally quotes Aristotele, Averroe, Plutarco, Valerio Probo, Sepulveda, Francisco de Tamara, Vartamano, Vesalio; also Autuario, a medieval Greek author known to him through a Latin translation by Ruelio.

Garcia felt able to differ from these authorities, as he very frequently does, because he was a long way from Europe. "If I was in Spain [the term "Spain", derived from Hispania, was in his time the geographical designation for the entirety of the Iberian Peninsula that includes Portugal] I wouldn't dare to say anything against Galen and the Greeks;" this remark has been seen as the real key to the Colóquios.[5]

The original edition of the Colóquios

Goa was by no means a major publishing centre, although the first printing press in India was introduced there in 1556; in the words of historian Charles Ralph Boxer, the original edition of the Colóquios "probably contains more typographical errors than any other book ever issued from a printing-press". The errata consisted of twenty pages and noted that it was probably incomplete.[6] Garcia's printer is thought to have been João de Endem who began his career with Joao Quinquenio de Campania.[7]

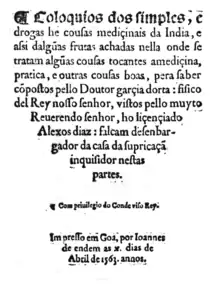

The original publication states very carefully the extent of its official backing. The title page carries the approval of the Viceroy and of the local Inquisitor "Alexos Diaz Falcam". The book opens with several commendatory letters and prefaces. Among these preliminaries, the one that is of most interest now is a poem, the first published verses by Garcia's friend Luís de Camões, now recognised as Portugal's national poet.

Many of the printing errors and authorial oversights are silently corrected in the 1872 reprint, which, although it follows the original page-for-page, is not a facsimile.

Reception of the Colóquios

Garcia de Orta was the first European to catalogue Indian medicinal herbs in their native habitat. His book was rapidly acknowledged as indispensable by scientists across Europe. Translations in Latin (then the scientific lingua franca) and other languages were made. The Latin translation, a slight abridgement dropping the dialogue format, but adding woodcut illustrations and editorial commentary, was by Charles de l'Écluse (Carolus Clusius). Clusius acquired his copy of the Colóquios at Lisbon on 28 December 1564,[8] and evidently continued to work on it all his life. In its final (fifth) edition, his translation forms a part of his great collaborative work, Exoticorum libri decem (1605).

Unluckily for the fame of Garcia da Orta's book, large parts of it were included with minimal acknowledgement in a similar work published in Spanish in 1578 by Cristóbal Acosta, Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de las Indias orientales ("Treatise of the drugs and medicines of the East Indies"). Da Costa's work was widely translated into vernacular languages and eventually lessened the fame of Garcia de Orta except among the few who were aware of the latter's originality.

There is an English translation of the Colóquios by Sir Clements Markham (1913) which included an introductory biography.

Editions of the Colóquios

- Colóquios dos simples e drogas he cousas medicinais da India e assi dalgũas frutas achadas nella onde se tratam algũas cousas ... boas pera saber. Goa: Ioannes de Endem, 1563

- Colloquios dos simples e drogas e cousas medicinaes da India e assi de algumas fructas achadas nella. Page-for-page reprint with introduction by F. Ad. de Varnhagen. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1872

- Colóquios, edited with commentary by the Count of Ficalho. 2 vols. Lisboa, 1891–1895

Translations of the Colóquios

- Aromatum et simplicium aliquot medicamentorum apud Indios nascentium historia: Latin translation by Carolus Clusius. Antwerp: Plantin, 1567

- Dell'historia dei semplici aromati et altre cose che vengono portate dall'Indie Orientali pertinenti all'uso della medicina ... di Don Garzia dall'Horto. Italian translation by Annibale Briganti, based on Clusius's Latin. Venice: Francesco Ziletti, 1589

- 5th edition of Clusius's Latin translation, forming part of his Exoticorum libri decem. Leiden, 1605

- Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India by Garcia da Orta. English translation by Sir Clements Markham. London, 1913

References

- ↑ Dialogue 17 (Roddis 1931, p. 203).

- ↑ Ball, Valentine (1891). "A Commentary on the Colloquies of Garcia de Orta, on the Simples, Drugs, and Medicinal Substances of India: Part I". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 1: 381–415. JSTOR 20503854.

- ↑ Dannenfeldt, Karl H. (1982). "Ambergris: The Search for Its Origin". Isis. 73 (3): 382–397. doi:10.1086/353040. PMID 6757176. S2CID 30323379.

- ↑ Dialogue 9 (Boxer 1963, p. 14).

- ↑ Dialogue 32 (Ficalho 1886, p. 309).

- ↑ Boxer 1963, p. 13.

- ↑ Primrose, J.B. (1939). "The first press in India and its printers". Library. 20 (3): 241–265. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XX.3.241.

- ↑ Boxer 1963, plate 2.

Notes

- ↑ The full title, in the original 1563 outdated spelling, is Colóquios dos simples, e drogas he cousas mediçinais da Índia, e assi dalgũas frutas achadas nella onde se tratam algũas cousas tocantes amediçina, pratica, e outras cousas boas, pera saber, literally, "Colloquies on the simples, drugs and materia medica of India, and also on some of the fruits found there, and wherein matters are dealt with concerning practical medicine and other goodly things to know".

References

- Boxer, C. R. (1963), Two pioneers of tropical medicine: Garcia d'Orta and Nicolás Monardes, London: Wellcome Historical Medical Library

- Carvalho, Augusto da Silva, Garcia de Orta. Lisboa, 1934.

- Ficalho, Francisco M., Conde de (1886), Garcia de Orta e o seu tempo, Lisbon

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (Reprinted: Lisboa: Casa da Moeda, 1983) - Roddis, Louis (1931), "Garcia da Orta, the first European writer on tropical medicine and a pioneer in pharmacognosy", Annals of Medical History, 1 (n. s.) (2): 198–207

External links

- a Costa, Christophori (1582). Aromatum et medicamentorum in Orientali India (in Latin). ex officina Christophori Plantini., Internet Archive

- Colloquies on the simples and drugs of India (English translation by Clements Markham 1913)

- 1563 edition (Portuguese)

- 1891 edition (Portuguese)

- Aromatum, et simplicium (1574) (Latin) Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine