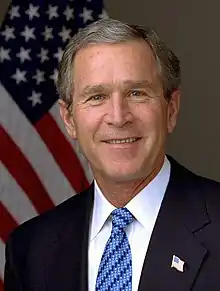

The Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act is an Act of the United States Congress introduced by John Lewis (GA-5) that allows the reopening of cold cases of suspected violent crimes committed against African Americans before 1970. The U.S. House of Representatives passed the legislation on June 20, 2007, by a vote of 422 to 2.[1] The U.S. Senate passed the legislation on September 24, 2008, by unanimous consent, and President George W. Bush signed the bill into law on October 7.[2]

Background

Background to legislation

During the Jim Crow era, the U.S. experienced a rise in violent crime against Black Americans.[3] A 2015 study found that almost four thousand lynchings, mostly of Black men, took place in Southern America between 1877 and 1950. This report compiled an increased number of such documented killings, most of which occurred in the decades around the turn of the 20th century.[4] Racially-based crimes followed accusations of criminal activity or behavior considered unacceptable for their racial group.[5]

Origin of the name of the act

Emmett Till was a fourteen-year-old Black boy from Chicago. In the summer of 1955, visiting family in Mississippi, Till was accused of whistling at, or flirting with, a young, married White woman in a grocery store. He then was abducted, beaten, mutilated, and shot in the head before his body was weighted down in a nearby river.[6] Till's murderers were tried but were acquitted by an all-white jury. The two men later confessed to killing Till in an interview with Life magazine. They were never retried or convicted for his murder.

The Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act, passed in 2008, authorized the federal government to reopen racially-based cold cases, especially from the civil rights era, for further investigation and prosecution.[3] The legislation was named for Till because his case is a famous example of a racial killing for which no one was successful tried. The bill works towards gathering more information on unsolved cases to uncover answers for family members, and solve cases using new information.[7]

Legislation

The Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act was first proposed in 2007 and was passed by Congress and signed by the president in 2008. In the House of Representatives, the original sponsors of the bill were Rep. John Lewis (D-Georgia), Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner, and Rep. John Conyers (D-Michigan). In the Senate, the effort was led by Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Missouri), Sen. Richard Burr (R-North Carolina), and Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vermont).[3]

The bill creates increased collaboration between local or state law enforcement, the FBI, and other elements of the Department of Justice. Overall, its primary purpose is to authorize investigation and prosecution of cold cases that appear related to civil rights violations. As of its authorization in 2008, the bill could apply to any case of a crime committed before December 31, 1969.

In addition, the bill provides for assisting the families of victims of civil rights crimes.[8]

Success

As a result of new investigations of cold cases from the Civil Rights era, several cases have been closed. As several suspects and witnesses have died in the intervening decades, there has been minimal prosecutions of perpetrators.[7]

As of 2015, only one case had made it to court and resulted in a successful prosecution.[9] The U.S. Department of Justice reopened the case of Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was fatally shot in Alabama in 1964 by James Fowler, a state police officer. He pleaded guilty to manslaughter and served six months in prison in 2010, leading to the closing of the case.[10]

Certain legal protections prevent prosecution in various cases. For example, the Fifth Amendment protects Americans from being tried twice on charges for which they have already been found not guilty.[9] Ex post facto clauses in the U.S. Constitution prevent individuals from being tried for crimes that were legal when committed, even if they are illegal now.[11] Given the length of time since the events, involved parties can be difficult to locate, or may have passed away, and evidence can be missing or destroyed.[9]

2016 Reauthorization

The Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act was reauthorized on December 16, 2016.[12] The Reauthorization Act contained a number of new provisions intended to increase success of the government's actions.[3] It aimed to connect the FBI, the Department of Justice, and law enforcement officers to organizations, such as universities or advocacy groups, that had also been investigating cold cases from the Civil Rights era. Other modifications to the bill included changing the time period to which the bill applied, including all cases before December 31, 1979, clarifying the purpose of the bill, urging the Department of Justice to review specific cases, and eliminating the sunset provision of the original bill, which stated that the bill expired at the end of the 2017 fiscal year.[3][8]

Related

References

- ↑ "H.R. 923 (110th): Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007".

- ↑ "H.R. 923 (110th): Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007".

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Reauthorization Act Passed by Congress". Congressman John Lewis. 2016-12-12. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ "History of Lynchings in the South Documents Nearly 4,000 Names". Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ "History of Lynching in America | NAACP". naacp.org. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Emmett Till". Biography. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- 1 2 "Civil Rights Division | Cold Case Initiative". www.justice.gov. 2015-08-06. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- 1 2 "Text of H.R. 923 (110th): Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007 (Introduced version) - GovTrack.us". GovTrack.us. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- 1 2 3 "Inside the Effort to Solve Civil Rights Crimes Before It's Too Late". Time. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ "Civil Rights Division | Jimmie Lee Jackson - Notice to Close File | United States Department of Justice". www.justice.gov. 2017-03-20. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "ex post facto". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Congressional Record, Vol. 162". www.govinfo.gov. December 16, 2016. Retrieved 2023-10-27.