John Eager Howard | |

|---|---|

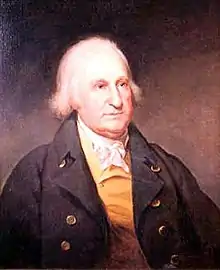

Oil painting of John Eager Howard by Charles Willson Peale (1823) | |

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate | |

| In office November 21, 1800 – November 27, 1800 | |

| Preceded by | Uriah Tracy |

| Succeeded by | James Hillhouse |

| United States Senator from Maryland | |

| In office November 21, 1796 – March 3, 1803 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Potts |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Smith |

| 5th Governor of Maryland | |

| In office November 24, 1788 – November 14, 1791 | |

| Preceded by | William Smallwood |

| Succeeded by | George Plater |

| Member of the Maryland Senate | |

| In office 1791–1795 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Eager Howard June 4, 1752 Baltimore County, Maryland, British America |

| Died | October 12, 1827 (aged 75) Baltimore County, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place | Old Saint Paul's Cemetery, (of Old St. Paul's Episcopal Church, cemetery at West Lombard Street and modern Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 9, including George, Benjamin, and William |

| Signature | |

John Eager Howard (June 4, 1752 – October 12, 1827) was an American soldier and politician from Maryland. He was elected as governor of the state in 1788, and served three one-year terms. He also was elected to the Continental Congress, the Congress of the United States and the U.S. Senate.[1] In the 1816 presidential election, Howard received 22 electoral votes for vice president on the Federalist Party ticket with Rufus King. The ticket lost in a landslide.

Howard County, Maryland, is named for him,[2] along with John Street, Eager Street and Howard Street in Baltimore. For seven days in November 1800, Howard was the President pro tempore of the United States Senate.

Early life and education

He was the son of Cornelius Howard and Ruth (Eager) Howard, of the Maryland planter elite and was born at their plantation "The Forest."[3] Howard grew up in an Anglican slaveholding family. Anglicanism was the established church of the Chesapeake Bay colonies.

Howard joined a Baltimore lodge of Freemasons.[2]

Military career

Commissioned a captain at the beginning of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), Howard rose in 1777 to the rank of colonel in the Maryland Line of the Continental Army,[1] fighting in the Battle of White Plains in New York State in 1776 and in the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey in 1778. He was awarded a silver medal by the Confederation Congress for his leadership at the 1781 Battle of Cowpens in South Carolina,[1] during which he commanded the 2nd Maryland Regiment, Continental Army.[4] In September 1781, he was wounded in a bayonet charge at the Battle of Eutaw Springs in South Carolina.[5] Southern Army commander Maj.Gen. Nathanael Greene wrote that Howard was "as good an officer as the world affords. He has great ability and the best disposition to promote the service....He deserves a statue of gold."[6]

At the conclusion of the war, Colonel Howard was admitted as an original member of The Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland when it was established in 1783.[7] He went on to serve as the vice president (1795–1804) and president of the Maryland Society (1804–1827), serving in the latter capacity until his death.[8]

Political life

Following his army service, Howard held several electoral political positions: elected to the Confederation Congress in 1788; fifth Governor of Maryland for three one-year terms (under first constitution of 1776), from 1788 through 1791; later as State Senator from 1791 through 1795; and Presidential Elector in the new 1787 Constitutional Electoral College set up in the presidential election of 1792. He declined the offer from first President George Washington in 1795 to be the second Secretary of War. He joined the newly organized Federalist Party and was elected to the 4th U.S. Congress from November 21, 1796, through 1797, by the General Assembly of Maryland (state legislature) to the upper chamber as United States Senator for the remainder of the term of Richard Potts, who had resigned. He was elected by the Legislature in Annapolis for a Senate term of his own in 1797, which included the 5th Congress, the 6th Congress of 1799–1801 during which he was President pro tempore, and the 7th Congress, serving until March 3, 1803.[1] While in Congress, he was the sole Federalist to vote against the Sedition Act.

Although Howard was offered an appointment as the Secretary of War in the administration of President George Washington, he declined it. Similarly, he also later declined a 1798 commission as Brigadier General in the newly organized United States Army during the preparations for the coming naval Quasi-War (1798–1800) with the new revolutionary French Republic (France).[1]

After 1803, Howard returned to Baltimore, where he avoided elected office but continued in public service and philanthropy as a leading citizen.[9] He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1815.[10] In the 1816 presidential election, he received 22 electoral votes for Vice President[2] as the running mate of Federalist Rufus King, losing to the Democratic-Republican candidates of James Monroe and Governor Daniel Tompkins. No formal Federalist nomination had been made, and it is not clear whether Howard himself, who was one of several Federalists who received electoral votes for vice president, actually wanted to run as a candidate for the office.

Howard developed property in the city of Baltimore and was active in city planning. His house was constructed near the city, where he owned slaves.[11]

Marriage and family

_and_Her_Son%252C_John_Eager_Howard_II.jpg.webp)

John Eager Howard married Margaret ("Peggy") Chew (1760–1824), daughter of the Pennsylvania justice Benjamin Chew, in 1787.[2]

- John Eager Howard Jr. (1788–1822) m.1820 Cornelia Read (daughter of US Senator Jacob Read, SC) Maryland State Senator. Died in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, October 1822.

- George Howard,[2] (1789–1846) m.1811 Prudence Ridgely (dau. of Gov. Charles Carnan Ridgely). George was born while Col. Howard was governor in Jennings House and became governor in 1831. His home "Waverly" at Marriottsville, Maryland still exists.

- Benjamin Chew Howard (1791–1872) m.1818 Jane Gilmor. He was elected for four terms in the U.S. Congress[2] and was the Reporter of Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States 1843–1861.

- Dr. William Howard (1793–1834) m.1828 Rebecca Key (dau. of Philip Barton Key, uncle of Francis Scott Key). He became a civil engineer for the War Department on canals and railroad routes.

- Juliana Howard McHenry (1796–1821) m.1819 John McHenry (died in Mercersburg, PA, Oct 1822; son of Dr. James McHenry, Secretary of War).

- James Howard (1797–1870) m.1820 Sophia Ridgely (dau. of Gov. Charles Carnan Ridgely) and 2d m.1832 Catherine Ross.

- Sophia Howard Read (1800–1880) m.1825 William George Read (son of US Sen. Jacob Read, SC)

- Charles Howard (1802–1869) m.1825 Elizabeth Key (dau. of Francis Scott Key). Charles and his son, Francis Key Howard, were imprisoned in Fort McHenry at the start of the American Civil War.[12]

- Mary (February–May 1806)

Death and legacy

John Eager Howard died in 1827. He is buried at the Old Saint Paul's Cemetery, located between West Lombard Street and present-day Martin Luther King Boulevard in Baltimore.[1]

- Howard County, Maryland, formed out of western Anne Arundel County and southeastern Frederick County in 1839 as the Howard District and officially as Howard County in 1851, was named for him.[2][13]

- In 1904, the city of Baltimore commissioned an equestrian statue of Howard by the eminent French sculptor Emmanuel Frémiet and installed it at Washington Place facing north from the north park up North Charles Street.[2]

- Howard is one of several notable men of Maryland mentioned in the state song "Maryland, My Maryland" written in 1861 by James Ryder Randall; the phrase "Howard's war-like thrust" refers to him.[14]

- Three streets in Baltimore share his name: the diagonal-running John Street in the Bolton Hill area; the east–west running Eager Street; and the north–south running Howard Street.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 United States Congress. "John Eager Howard (id: H000841)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Index to Politicians: Howard". The Political Graveyard. Lawrence Kestenbaum. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- ↑ "John Eager Howard (1752–1827)". Archives of Maryland. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ↑ "John Eager Howard (1752–1827)". Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series). Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ Nancy Capace. Encyclopedia of Maryland. p. 81.

- ↑ Quoted in Lawrence E. Babits, A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 26.

- ↑ Metcalf, Bryce (1938). Original Members and Other Officers Eligible to the Society of the Cincinnati, 1783–1938: With the Institution, Rules of Admission, and Lists of the Officers of the General and State Societies Strasburg, VA: Shenandoah Publishing House, Inc., p. 168.

- ↑ Metcalf, p. 22.

- ↑ American National Biography, John Eager Howard; online version consulted

- ↑ "American Antiquarian Society Members Directory". American Antiquarian Society. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ↑ Papenfuse, Edward C. (April 24, 2018). "Remembering John Eager Howard and His Vision for Baltimore". Remembering Baltimore. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

According to the 1820 census there were ... five slaves and seven free blacks.

- ↑ "The Provost-Marshal and the Citizen (in the American Civil War)". Home of the American Civil War. February 15, 2002. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 162.

- ↑ Hughes, William (December 2009). "'Cool Deliberate Courage: John Eager Howard in the American Revolution' Book Review". Media Monitors Network. Retrieved November 14, 2019 – via thepeoplesvoice.org.

- ↑ maxjpollock (February 2, 2015). "Why "Eager" Street?". Baltimore Brick By Brick. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

Further reading

- Jim Piecuch and John Beakes. Cool Deliberate Courage: John Eager Howard in the American Revolution (2009)

- Tony J. Lopez. "Courage at the Cowpens: The Colonel John Eager Howard Medal", The Numismatist, Vol. 122 No. 7 (July 2009): 40–47