In psychology, the Asch conformity experiments or the Asch paradigm were a series of studies directed by Solomon Asch studying if and how individuals yielded to or defied a majority group and the effect of such influences on beliefs and opinions.[1][2][3][4]

Developed in the 1950s, the methodology remains in use by many researchers. Uses include the study of conformity effects of task importance,[5] age,[6] sex,[7][8][9][10] and culture.[5][10]

Initial conformity experiment

Rationale

Many early studies in social psychology were adaptations of earlier work on "suggestibility" whereby researchers such as Edward L. Thorndyke were able to shift the preferences of adult subjects towards majority or expert opinion.[3] Still the question remained as to whether subject opinions were actually able to be changed, or if such experiments were simply documenting a Hawthorne effect in which participants simply gave researchers the answers they wanted to hear. Solomon Asch's experiments on group conformity mark a departure from these earlier studies by removing investigator influence from experimental conditions.

In 1951, Asch conducted his first conformity laboratory experiments at Swarthmore College, laying the foundation for his remaining conformity studies. The experiment was published on two occasions.[1][11]

Method

Groups of eight male college students participated in a simple "perceptual" task. In reality, all but one of the participants were actors, and the true focus of the study was about how the remaining participant would react to the actors' behavior.

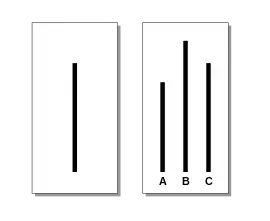

The actors knew the true aim of the experiment, but were introduced to the subject as other participants. Each student viewed a card with a line on it, followed by another with three lines labeled A, B, and C (see accompanying figure). One of these lines was identical in length to that on the first card, and the other two lines were clearly longer or shorter (i.e., a near-100% rate of correct responding was expected). Each participant was then asked to say aloud which line matched the length of that on the first card. Before the experiment, all actors were given detailed instructions on how they should respond to each trial (card presentation). They would always unanimously nominate one comparator, but on certain trials they would give the correct response and on others, an incorrect response. The group was seated such that the real participant always responded last.

Subjects completed 18 trials. On the first two trials, both the subject and the actors gave the obvious, correct answer. On the third trial, the actors would all give the same wrong answer. This wrong-responding recurred on 11 of the remaining 15 trials. It was subjects' behavior on these 12 "critical trials" (the 3rd trial + the 11 trials where the actors gave the same wrong answer) that formed the aim of the study: to test how many subjects would change their answer to conform to those of the 7 actors, despite it being wrong. Subjects were interviewed after the study including being debriefed about the true purpose of the study. These post-test interviews shed valuable light on the study—both because they revealed subjects often were "just going along", and because they revealed considerable individual differences to Asch. Additional trials with slightly altered conditions were also run,[1] including having a single actor also give the correct answer.

Asch's experiment also had a condition in which participants were tested alone with only the experimenter in the room. In total, there were 50 subjects in the experimental condition and 37 in the control condition.

Results

In the control group, with no pressure to conform to actors, the error rate on the critical stimuli was less than 0.7%.[1]

In the actor condition also, the majority of participants' responses remained correct (64.3%), but a sizable minority of responses conformed to the actors' (incorrect) answer (35.7%). The responses revealed strong individual differences: 12% of participants followed the group in nearly all of the tests. 26% of the sample consistently defied majority opinion, with the rest conforming on some trials. An examination of all critical trials in the experimental group revealed that one-third of all responses were incorrect. These incorrect responses often matched the incorrect response of the majority group (i.e., actors). Overall, 74% of participants gave at least one incorrect answer out of the 12 critical trials.[1] Regarding the study results, Asch stated: "That intelligent, well-meaning young people are willing to call white black is a matter of concern."

Interview responses

Participants' interview responses revealed a complex mixture of individual differences in subjects' reaction to the experimental situation, with distinct reactions linked to factors such as confidence, self-doubt, the desire to be normative, and resolving perceived confusion over the nature of the task.

Asch's report included interviews of a subject that remained "independent" and another that "yielded". Each provided a descriptive account following disclosure of the true nature of the experiment. The "independent" subject said that he felt happy and relieved and added, "I do not deny that at times I had the feeling: 'to go with it [...] I'll go along with the rest.'"[12]: 182 At the other end of the spectrum, one "yielding" subject (who conformed in 11 of 12 critical trials) said, "I suspected about the middle—but tried to push it out of my mind."[12]: 182 Asch points out that although the "yielding" subject was suspicious, he was not sufficiently confident to go against the majority.

Attitudes of independent responders

Subjects who did not conform to the majority reacted either with "confidence": they experienced conflict between their idea of the obvious answer and the group's incorrect answer, but stuck with their own answer, or were "withdrawn". These latter subjects stuck with their perception but did not experience conflict in doing so. Some participants also exhibited "doubt", responding in accordance with their perception, but questioning their own judgment while nonetheless sticking to their (correct) response, expressing this as needing to behave as they had been asked to do in the task.

Attitudes of responders conforming on one or more trials

Participants who conformed to the majority on at least 50% of trials reported reacting with what Asch called a "distortion of perception". These participants, who made up a distinct minority (only 12 subjects), expressed the belief that the actors' answers were correct, and were apparently unaware that the majority were giving incorrect answers.

Among the other participants who yielded on some trials, most expressed what Asch termed "distortion of judgment". These participants concluded after a number of trials that they must be wrongly interpreting the stimuli and that the majority must be right, leading them to answer with the majority. These individuals were characterized by low levels of confidence. The final group of participants who yielded on at least some trials exhibited a "distortion of action". These subjects reported that they knew what the correct answer was, but conformed with the majority group simply because they didn't want to seem out of step by not going along with the rest.[12] All conforming respondents underestimated the frequency with which they conformed to the majority.[3]

Variations on the original paradigm

In subsequent research experiments, Asch explored several variations on the paradigm from his 1951 study.[2]

In 1955 he reported on work with 123 male students from three different universities.[3] A second paper in 1956 also consisted of 123 male college students from three different universities,:[4] Asch did not state if this was in fact the same sample as reported in his 1955 paper: The principal difference is that the 1956 paper includes an elaborate account of his interviews with participants. Across all these papers, Asch found the same results: participants conformed to the majority group in about one-third of all critical trials.

- Presence of a true partner

- Asch found that the presence of a "true partner" (a "real" participant or another actor told to give the correct response to each question) decreased conformity.[1][3] In studies that had one actor give correct responses to the questions, only 5% of the participants continued to answer with the majority.[13] In subsequent interviews, subjects claimed a degree of "warmth" and "closeness" towards the partner, and attributed an increase in confidence to their presence. Still, subjects rejected the notion that it was the partner who allowed them to answer independently.

Partner dissent and accuracy

- Experiments were also designed to determine if the partner effect on subject conformity was due to the partner's dissent from the majority or their accuracy in answering questions.[3][4] In one experiment, Asch identified two classes of dissenter: "extremist" (under this condition, dissenters always chose the worst of the comparison lines and the majority chose the line closest to the standard in length) and "compromising" (dissenter: closest to standard; majority: worst comparison line). In compromising dissenter trials, subject conformity decreased overall and when they did conform, they conformed to the dissenter, not the majority. Compromising dissenters were seen to control the "choice of errors". In trials with an extremist dissenter, subject conformity decreased dramatically with only 9% of respondents continuing to answer with the majority. Therefore, partner dissent was found to increase independence, moderating errors (conformity).

- Withdrawal of a partner

- Asch also examined whether the removal of a true partner partway through the experiment influenced participants' level of conformity.[1][3] He found low levels of conformity during the first half of the experiment. However, halfway through the experiment the partner rejoined the majority, answering in lockstep with the group. When their partner switched, the subject conformity rose to levels consistent to if they had never had a partner at all. Asch classified this finding as a "desertion" effect. In a variant of this study, the partner left the experiment halfway-through altogether (an excuse was provided for their departure). Under these conditions, the partner's influence lingered through the second half of the experiment; the subject's conformity to the group increased after the partner's departure, but not as drastically if the partner was perceived as having switched sides.[3]

- Majority size

- Asch also examined whether decreasing or increasing the majority size had an influence on participants' level of conformity.[1][2][3] When paired with a single individual who opposed their answers, the subject retained high levels of independence in their answers. Increasing the opposing group to two or three persons increased conformity substantially. Increases beyond three persons (e.g., four, five, six, etc.) did not further-increase conformity.

- Written responses

- Asch also varied the method of participants' responding in studies where actors verbalized their responses aloud but the "real" participant responded in writing at the end of each trial. Conformity significantly decreased when shifting from public to written responses.[4]

Degree of wrongness

- Another research question examined by Asch was whether varying the magnitude of majority "wrongness" affected subject conformity to group norms.[3] To answer this question, the difference between the reference line and three comparison lines was systematically increased to determine if there was a point where the extremity of the majority's error affected subject conformity. The authors failed to find a point at which subject conformity to the majority was completely eliminated, even when the disparity between lines was increased to 7 inches.

Interpretations

Normative influence vs. referent informational influence

The Asch conformity experiments are often interpreted as evidence for the power of conformity and normative social influence,[14][15][16] where normative influence is the willingness to conform publicly to attain social reward and avoid social punishment.[17] From this perspective, the results are viewed as a striking example of people publicly endorsing the group response despite knowing full well that they were endorsing an incorrect response.[18][19]

Similarly, Jerry M. Burger admits the normative influence effect of the experiment in Chapter 21 of Noba online book.[20] He mentioned that people follow the crowd to avoid potential criticism. During Asch's experiment, participants choose the wrong answer to keep the association with the group. The demonstration in this experiment broadens people's understanding of the large application of normative influence. To stay consistent with other group members, people may follow a trend that is apparently wrong. Moreover, the behavior of normative conformity may reduce when the individual response is not accessible to other people.[21] This phenomenon further stresses the social role in normative influence.

In contrast, John Turner and colleagues argue that the interpretation of the Asch conformity experiments as normative influence is inconsistent with the data.[14][15][16] They point out that post-experiment interviews revealed that participants experienced uncertainty about their judgement during the experiments. Although the correct answer appeared obvious to the researchers, this was not necessarily the experience of participants. Subsequent research has demonstrated similar patterns of conformity where participants were anonymous and thus not subject to social punishment or reward on the basis of their responses.[22] From this perspective, the Asch conformity experiments are viewed as evidence for the self-categorization theory account of social influence (otherwise known as the theory of referent informational influence).[14][15][16][23][24][25] Here, the observed conformity is an example of depersonalization processes, whereby people expect to hold the same opinions as others in their ingroup and will often adopt those opinions.

Social comparison theory

The conformity demonstrated in Asch experiments may contradict aspects of social comparison theory.[14][15][26] Social comparison theory suggests that, when seeking to validate opinions and abilities, people will first turn to direct observation. If direct observation is ineffective or not available, people will then turn to comparable others for validation.[27] In other words, social comparison theory predicts that social reality testing will arise when physical reality testing yields uncertainty. The Asch conformity experiments demonstrate that uncertainty can arise as an outcome of social reality testing. More broadly, this inconsistency has been used to support the position that the theoretical distinction between social reality testing and physical reality testing is untenable.[15][16][28][29]

Selective representation in textbooks and the media

Asch's 1956 report emphasized the predominance of independence over yielding saying "the facts that were being judged were, under the circumstances, the most decisive."[4] However, a 1990 survey of US social psychology textbooks found that most ignored independence, instead reported a misleading summary of the results as reflecting complete power of the situation to produce conformity of behavior and belief.[30]

A 2015 survey found no change, with just 1 of 20 major texts reporting that most participant-responses defied majority opinion. No text mentioned that 95% of subjects defied the majority at least once. Nineteen of the 20 books made no mention of Asch's interview data in which many participants said they were certain all along that the actors were wrong.[31] This portrayal of the Asch studies was suggested to fit with social psychology narratives of situationism, obedience and conformity, to the neglect of recognition of disobedience of immoral commands (e.g., disobedience shown by participants in Milgram Studies), desire for fair treatment (e.g., resistance to tyranny shown by many participants in the Stanford prison studies) and self-determination.[31]

See also

- Bandwagon effect – Societal phenomenon

- Collective responsibility – Responsibility of organizations, groups and societies

- Communal reinforcement – Social phenomenon

- Conformity – Matching opinions and behaviors to group norms

- Crutchfield situation – Experimental procedure and apparatus to study conformity.

- Confirmation bias – Bias confirming existing attitudes

- Groupthink – Psychological phenomenon that occurs within a group of people

- Information cascade – Behavioral phenomenon

- Milgram experiment – Series of social psychology experiments

- Muzafer Sherif – Turkish-American psychologist (1906–1988)

- Normative social influence – Type of social influence

- Overton window – Range of ideas tolerated in public discourse

- Peer pressure – Influencing peers to conform

- Social influence – Alteration of attitudes and behaviors based on outside influences

- Spiral of silence – Political science and mass communication theory

- Stanford prison experiment – Controversial 1971 psychological experiment

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Asch, Solomon (1951). "Effects of group pressure on the modification and distortion of judgments". Groups, Leadership and Men: Research in Human Relations. Carnegie Press. pp. 177–190. ISBN 978-0-608-11271-8.

- 1 2 3 Asch, S.E. (1952b). "Social psychology". Englewood Cliffs, NJ:Prentice Hall.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Asch, S.E. (1955). "Opinions and social pressure". Scientific American. 193 (5): 31–35. Bibcode:1955SciAm.193e..31A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1155-31. S2CID 4172915.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Asch, S.E. (1956). "Studies of independence and conformity. A minority of one against a unanimous majority". Psychological Monographs. 70 (9): 1–70. doi:10.1037/h0093718.

- 1 2 Milgram, S (1961). "Nationality and conformity". Scientific American. 205 (6): 6. Bibcode:1961SciAm.205f..45M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1261-45.

- ↑ Pasupathi, M (1999). "Age differed in response to conformity pressure for emotional and nonemotional material". Psychology and Aging. 14 (1): 170–74. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.14.1.170. PMID 10224640.

- ↑ Cooper, H.M. (1979). "Statistically combined independent studies: A meta-analysis of sex differences in conformity research". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37: 131–146. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.1.131.

- ↑ Eagly, A.H. (1978). "Sex differences in influenceability". Psychological Bulletin. 85: 86–116. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.85.1.86.

- ↑ Eagly, A.H.; Carli, L. (1981). "Sex of researchers and sex-typed communications as determinants of sex differed in influenceability: A meta-analysis of social influence studies". Psychological Bulletin. 90 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.90.1.1.

- 1 2 Bond, R.; Smith, P.B. (1996). "Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch's (1952b, 1956) line judgement task" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 119 (1): 111–137. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.111. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- ↑ Asch, S. E. (1952a). Effects of group pressure on the modification and distortion of judgments. In G. E. Swanson, T. M. Newcomb & E. L. Hartley (Eds.), Readings in social psychology (2nd ed., pp. 2–11). New York: Holt.

- 1 2 3 Asch, S.E. (1951). Effects of group pressure on the modification and distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups, leadership and men (pp. 177–190). Pittsburgh, PA:Carnegie Press.

- ↑ Morris; Miller (1975). "The effects of consensus-breaking and consensus-preempting partners on reduction in conformity". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 11 (3): 215–223. doi:10.1016/s0022-1031(75)80023-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Turner, J.C. (1985). Lawler, E. J (ed.). "Social categorization and the self-concept: A social cognitive theory of group behavior". Advances in Group Processes: Theory and Research. Greenwich, CT. 2: 77–122.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D. & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford: Blackwell

- 1 2 3 4 Turner, J. C. (1991). Social influence. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- ↑ Deutsch, M.; Harold, G. (1955). "A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgement". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 51 (3): 629–636. doi:10.1037/h0046408. PMID 13286010.

- ↑ Aronson, T. D.; Wilson, R. M.; Akert, E. (2010). Social Psychology (7 ed.). Pearson.

- ↑ Anderson, C.A. (2010). Social Psychology. Wiley.

- ↑ Rhodes, Marjorie. "NYU: Introduction to Psychology Spring 2019". Noba. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ↑ Bond, R., & Smith, P. B. (1996). Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch’s (1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 111–137.

- ↑ Hogg, M. A.; Turner, J. C. (1987). Doise, W.; Moscivici, S. (eds.). "Social identity and conformity: A theory of referent informational influence". Current Issues in European Social Psychology. Cambridge. 2: 139–182.

- ↑ Turner, J.C. (1982). Tajfel, H. (ed.). "Toward a cognitive redefinition of the social group". Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. Cambridge, UK: 15–40.

- ↑ Haslam, A. S. (2001). Psychology in Organizations. London, SAGE Publications.

- ↑ Haslam, S. Alexander; Reicher, Stephen D.; Platow, Michael J. (2011). The new psychology of leadership: Identity, influence and power. New York, NY: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-84169-610-2.

- ↑ Turner, John; Oakes, Penny (1986). "The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence". British Journal of Social Psychology. 25 (3): 237–252. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1986.tb00732.x.

- ↑ Festinger, L (1954). "A theory of social comparison processes". Human Relations. 7 (2): 117–140. doi:10.1177/001872675400700202. S2CID 18918768.

- ↑ Turner, J. C.; Oakes, P. J. (1997). McGarty, C.; Haslam, S. A. (eds.). "The socially structured mind". The Message of Social Psychology. Cambridge, MA: 355–373.

- ↑ Turner, J. C. (2005). "Explaining the nature of power: A three-process theory". European Journal of Social Psychology. 35: 1–22. doi:10.1002/ejsp.244.

- ↑ Friend, R.; Rafferty, Y.; Bramel, D. (1990). "A puzzling misinterpretation of the Asch 'conformity' study". European Journal of Social Psychology. 20: 29–44. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420200104.

- 1 2 Griggs, R. A. (2015). "The Disappearance of Independence in Textbook Coverage of Asch's Social Pressure Experiments". Teaching of Psychology. 42 (2): 137–142. doi:10.1177/0098628315569939. S2CID 146908363.

Bibliography

- Asch, S. E. (1940). "Studies in the principles of judgments and attitudes: II. Determination of judgments by group and by ego-standards". Journal of Social Psychology. 12 (2): 433–465. doi:10.1080/00224545.1940.9921487.

- Asch, S. E. (1948). "The doctrine of suggestion, prestige and imitation in social psychology". Psychological Review. 55 (5): 250–276. doi:10.1037/h0057270. PMID 18887584.

- Coffin, E. E. (1941). "Some conditions of suggestion and suggestibility: A study of certain attitudinal and situational factors influencing the process of suggestion". Psychological Monographs. 53 (4): i-125. doi:10.1037/h0093490.

- Lewis, H.B. (1941). "Studies in the principles of judgements and attitudes: IV. The operation of prestige suggestion". Journal of Social Psychology. 14: 229–256. doi:10.1080/00224545.1941.9921508.

- Lorge, I (1936). "Prestige, suggestion, and attitudes". Journal of Social Psychology. 7 (4): 386–402. doi:10.1080/00224545.1936.9919891.

- Miller, N.E. & Dollard, J. (1941). Social learning and imitation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Moore, H.T. (1921). "The comparative influence of majority and expert opinion". American Journal of Psychology. 32 (1): 16–20. doi:10.2307/1413472. JSTOR 1413472.

- Sherif, M.A. (1935). "A study of some social factors in perception". Archives of Psychology. 27: 1–60.

- Thorndike, E. L. The psychology of wants, interests, and attitudes. New York, NY: D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc.

- The Asch Experiment:Youtube video. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.