The landed gentry, or the gentry, is a largely historical British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. While distinct from, and socially below, the British peerage, their economic base in land was often similar, and some of the landed gentry were wealthier than some peers. Many gentry were close relatives of peers, and it was not uncommon for gentry to marry into peerage. It is the British element of the wider European class of gentry. With or without noble title, owning rural land estates often brought with it the legal rights of lord of the manor, and the less formal name or title of squire, in Scotland laird.

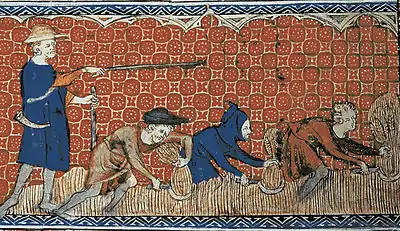

Generally lands passed by primogeniture, while the inheritances of daughters and younger sons were in cash or stocks, and relatively small. Typically the gentry farmed some of their land, but leased most of it to tenant farmers. They also exploited timber and minerals (such as coal), and owned mills and other sources of income. Many heads of families also had careers in politics or the military, and the younger sons of the gentry provided a high proportion of the clergy, military officers, and lawyers.

The decline of the gentry largely began with the 1870s agricultural depression; however, there are still many hereditary gentry in the UK.

The designation landed gentry originally referred exclusively to members of the upper class who were both landlords and commoners (in the British sense)-—that is, they did not hold peerages. But by the late 19th century, the term was also applied to peers, such as the Duke of Westminster, who lived on landed estates.

Successful burghers often used their accumulated wealth to buy country estates, with the aim of establishing themselves as landed gentry.

The book series Burke's Landed Gentry records the names of members of this class.

Origin of the term

The term landed gentry, originally referred to all members of the nobility; beginning around 1540 in England, it came to refer only to the lesser nobility. Later, the two terms came to have more distinct meanings. Not all landed gentry were members of the nobility, and not all members of the nobility owned landed estates. The historical term gentry by itself, so Peter Coss argues, has been used rather loosely by historians to refer to rather different classes of people in different societies.[2][3] But the phrase landed gentry has been used specifically to refer to the members of the landowning upper class who do not have noble titles. The most stable and respected form of wealth has historically been land, and great prestige and political qualifications were (and to a lesser extent still are) attached to land ownership.

Definitions

The term gentry, some of whom were landed, included four separate groups in England:[4]

- Baronets: a hereditary title, originally created in the 14th century and revived by King James in 1611, giving the holder the right to be addressed as Sir.

- Knights: originally a military rank, this status was increasingly awarded to civilians as a reward for service to the Crown. Holders have the right to be addressed as Sir, as are baronets, but unlike baronet, the title of knight is not hereditary (with the exception of the Knight of Kerry, the Knight of Glin, and the White Knight).

- Esquires: originally men aspiring to knighthood, they were the principal attendants on a knight. After the Middle Ages the title of Esquire (Esq.) became an honour that could be conferred by the Crown, and by custom the holders of certain offices (such as barristers, lord mayor/mayor, justices of the peace, and higher officer ranks in the armed services) were deemed to be Esquires.[5]

- Gentlemen: possessors of a social status recognised as a separate title by the Statute of Additions of 1413.[6] Generally men of high birth or rank, good social standing and wealth, and who did not need to work for a living, were considered gentlemen.

All of the first group, and very many of the last three, were armigerous, having obtained the right to display a coat of arms. In many Continental societies, this was exclusively the right of the nobility, and at least the upper clergy. In France this was originally true but many of the landed gentry, burghers (sometimes known as burgesses) and wealthy merchants were also allowed to register coats of arms and become "armigerous".

Development

The primary meaning of landed gentry encompasses those members of the land-owning classes who are not members of the peerage. It was an informal designation: one belonged to the landed gentry if other members of that class accepted one as such. A newly rich man who wished his family to join the gentry (and they nearly all did so wish), was expected not only to buy a country house and estate, but often also to sever financial ties with the business which had made him wealthy in order to cleanse his family of the "taint of trade", depending somewhat on what that business was. However, during the 18th and 19th centuries, as the new rich of the Industrial Revolution became more and more numerous and politically powerful, this expectation was gradually relaxed. From the late 16th-century, the gentry emerged as the class most closely involved in politics, the military and law. It provided the bulk of Members of Parliament, with many gentry families maintaining political control in a certain locality over several generations (see List of political families in the United Kingdom). Owning land was a prerequisite for suffrage (the civil right to vote) in county constituencies until the Reform Act 1832; until then, Parliament was largely in the hands of the landowning class.

Members of the landed gentry were upper class (not middle class); this was a highly prestigious status. Particular prestige was attached to those who inherited landed estates over a number of generations. These are often described as being from "old" families. Titles are often considered central to the upper class, but this is certainly not universally the case. For example, both Captain Mark Phillips and Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence, the first and second husbands of the Princess Anne, lacked any rank of peerage, yet could scarcely be considered anything other than upper class.

The agricultural sector's middle class, on the other hand, comprise the larger tenant farmers, who rent land from the landowners, and yeoman farmers, who were defined as "a person qualified by possessing free land of forty shillings annual [feudal] value, and who can serve on juries and vote for a Knight of the Shire. He is sometimes described as a small landowner, a farmer of the middle classes."[7] Anthony Richard Wagner, Richmond Herald wrote that "a Yeoman would not normally have less than 100 acres" (40 hectares) and in social status is one step down from the gentry, but above, say, a husbandman.[8] So while yeoman farmers owned enough land to support a comfortable lifestyle, they nevertheless farmed it themselves and were excluded from the "landed gentry" because they worked for a living, and were thus "in trade" as it was termed. Apart from a few "honourable" professions connected with the governing elite (the clergy of the established church, the officer corps of the British Armed Forces, the diplomatic and civil services, the bar or the judiciary), such occupation was considered demeaning by the upper classes, particularly by the 19th century, when the earlier mercantile endeavours of younger sons were increasingly discontinued. Younger sons, who could not expect to inherit the family estate, were instead urged into professions of state service. It became a pattern in many families that while the eldest son would inherit the estate and enter politics, the second son would join the army, the third son go into law, and the fourth son join the church.[9]

Landed gentry and nobility

Persons who are closely related to peers are also more correctly described as gentry than as nobility, since the latter term, in the modern British Isles, is synonymous with peer. However, this popular usage of nobility omits the distinction between titled and untitled nobility. The titled nobility in Britain are the peers of the realm, whereas the untitled nobility comprise those here described as gentry.[10][11]

David Cannadine wrote that the gentry's lack of titles "did not matter, for it was obvious to contemporaries that the landed gentry were all for practical purposes the equivalent of continental nobles, with their hereditary estates, their leisured lifestyle, their social pre-eminence, and their armorial bearings".[12] British armigerous families who hold no title of nobility are represented, together with those who hold titles through the College of Arms, by the Commission and Association for Armigerous Families of Great Britain at CILANE. Through grants of arms, new families are admitted into the untitled nobility regularly, thus making the gentry a class that remains open both legally and practically.[13]

Burke's Landed Gentry and Burke's Peerage

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the names and families of those with titles (specifically peers and baronets, less often including those with the non-hereditary title of knight) were often listed in books or manuals known as "Peerages", "Baronetages", or combinations of these categories, such as the "Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage, and Companionage". As well as listing genealogical information, these books often also included details of the right of a given family to a coat of arms. They were comparable to the Almanach de Gotha in continental Europe.[14] Novelist Jane Austen, whose family were not quite members of the landed gentry class,[15] summarised the appeal of these works, particularly for those included in them:

Sir Walter Elliot, of Kellynch Hall, in Somersetshire, was a man who, for his own amusement, never took up any book but the Baronetage; there he found occupation for an idle hour, and consolation in a distressed one; there his faculties were roused into admiration and respect, by contemplating the limited remnant of the earliest patents; there any unwelcome sensations, arising from domestic affairs changed naturally into pity and contempt as he turned over the almost endless creations of the last century; and there, if every other leaf were powerless, he could read his own history with an interest which never failed.

— Jane Austen, Persuasion, chapter 1, page 1

Equally wryly, Oscar Wilde referred to the Peerage as "the best thing in fiction the English have ever done".[16]

In the 1830s, one peerage publisher, John Burke, expanded his market and his readership by publishing a similar volume for people without titles, which was called A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, enjoying territorial possessions or high official rank, popularly known as Burke's Commoners. Burke's Commoners was published in four volumes from 1833 to 1838.[17][18]

Subsequent editions were re-titled A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry; or, Commons of Great Britain and Ireland or Burke's Landed Gentry.[18]

Burke's Landed Gentry continued to appear at regular intervals throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, driven, in the 19th century, principally by the energy and readable style of the founder's son and successor as editor, Sir John Bernard Burke (who generally favoured the romantic and picturesque in genealogy over the mundane, or strictly correct).

A review of the 1952 edition in Time noted:

Landed Gentry used to limit itself to owners of domains that could properly be called "stately" (i.e. more than 500 acres or 200 hectares). Now it has lowered the property qualification to 200 acres (0.81 km2) for all British families whose pedigrees have been "notable" for three generations. Even so, almost half of the 5,000 families listed in the new volume are in there because their forefathers were: they themselves have no land left. Their estates are mere street addresses, like that of the Molineux-Montgomeries, formerly of Garboldisham Old Hall, now of No. 14 Malton Avenue, Haworth.[19]

The last three-volume edition of Burke's Landed Gentry was published between 1965 and 1972. A new series, under new owners, was begun in 2001 on a regional plan, starting with Burke's Landed Gentry; The Kingdom in Scotland. However, these volumes no longer limit themselves to people with any connection, ancestral or otherwise, with land, and they contain much less information, particularly on family history, than the 19th and 20th century editions.

The popularity of Burke's Landed Gentry gave currency to the expression Landed Gentry as a description of the untitled upper classes in England (although the book also included families in Wales, Scotland and Ireland, where, however, social structures were rather different).

Families were arranged in alphabetical order by surname, and each family article was headed with the surname and the name of their landed property, e.g. "Capron of Southwick Hall". There was then a paragraph on the owner of the property, with his coat of arms illustrated, and all his children and remoter male-line descendants also listed, each with full names and details of birth, marriage, death, and any matters tending to enhance their social prestige, such as school and university education, military rank and regiment, Church of England cures held, and other honours and socially approved involvements. Cross references were included to other families in Burke's Landed Gentry or in Burke's Peerage and Baronetage: thus encouraging browsing through connections. Professional details were not usually mentioned unless they conferred some social status, such as those of civil service and colonial officials, judges and barristers.

After the section dealing with the current owner of the property, there usually appeared a section entitled Lineage which listed, not only ancestors of the owner, but (so far as known) every male-line descendant of those ancestors.

Contemporary status

The Great Depression of British Agriculture at the end of the 19th century, together with the introduction in the 20th century of increasingly heavy levels of taxation on inherited wealth, put an end to agricultural land as the primary source of wealth for the upper classes. Many estates were sold or broken up, and this trend was accelerated by the introduction of protection for agricultural tenancies, encouraging outright sales, from the mid-20th century.[20][21][22]

So devastating was this for the ranks formerly identified as being of the landed gentry that Burke's Landed Gentry began, in the 20th century, to include families historically in this category who had ceased to own their ancestral lands. The focus of those who remained in this class shifted from the lands or estates themselves, to the stately home or "family seat" which was in many cases retained without the surrounding lands. Many of these buildings were purchased for the nation and preserved as monuments to the lifestyles of their former owners (who sometimes remained in part of the house as lessees or tenants) by the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. The National Trust, which had originally concentrated on open landscapes rather than buildings, accelerated its country house acquisition programme during and after the Second World War, partly because of the widespread destruction of country houses in the 20th century by owners who could no longer afford to maintain them. Those who retained their property usually had to supplement their incomes from sources other than the land, sometimes by opening their properties to the public.

In the 21st century, the term "landed gentry" is still used, as the landowning class still exists, but it increasingly refers more to historic than to current landed wealth or property in a family. Moreover, the deference which was once automatically given to members of this class by most British people has almost completely dissipated as its wealth, political power and social influence have declined, and other social figures such as celebrities have grown to take their place in the public's interest.

See also

References

- ↑ "Gainsborough by James Hamilton review – the painter's secret sauciness". The Guardian. 17 August 2017.

- ↑ "The Origins of the English Gentry | Reviews in History". www.history.ac.uk.

- ↑ "Cambridge University Press 0521021006 - The Origins of the English Gentry Peter Coss" (PDF).

- ↑ Canon, John, The Oxford Companion to British History, p. 405 under the heading "Gentry" (Oxford University Press, 1997)

- ↑ Heal, Felicity (1994). The Gentry in England and Wales, 1500-1700. Stanford University Press. p. 230. ISBN 9780804724487.

(By the late 17th century)....a number of local squires were added to the governing bodies, even appointed as mayors...

- ↑ Cross, Peter (2003). "The formation of the English gentry" (PDF). The Origins of the English Gentry. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780521826730.

- ↑ See The Concise Oxford Dictionary, edited by H.W. & F.G.Fowler, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1972 reprint, p. 1516; note the definition does not apply to 1972, but to an earlier time.

- ↑ English Genealogy, Oxford, 1965, pps: 125–30.

- ↑ Patrick Wallis and Cliff Webb, The education and training of gentry sons in early modern England http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/27958/1/WP128.pdf

- ↑ "Esquire", Penny cyclopedia, vol. 9–10, Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, 1837, p. 13, retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ Larence, Sir James Henry (1827) [1824]. The nobility of the British Gentry or the political ranks and dignities of the British Empire compared with those on the continent (2nd ed.). London: T.Hookham -- Simpkin and Marshall.

- ↑ Cannadine, David (1999). The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy. Vintage Books.

- ↑ C.i.l.a.n.e. United Kingdom: Ediciones Hidalguia. 1989. p. 5. ISBN 978-84-89851-20-7.

- ↑ de Diesbach, Ghislain (1967). Secrets of the Gotha. Meredith Press. ISBN 978-1-5661908-6-2.

- ↑ Copeland, Edward; McMaster, Juliet (2011). The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521763080.

- ↑ A Woman of No Importance, Lord Illingworth to his son Gerald Arbuthnot

- ↑ Ormerod, George (1907). Index to the Pedigree in Burke's Commoners: Originally Prepared by George Ormerod in 1840. Provost of Queen's College.

- 1 2 "Burke's Peerage and Landed Gentry Database Search". ukga.org. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ "Foreign News: Twentieth Century Squires". Time. 10 December 1951. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ↑ Fletcher, T. W. (1973). "The Great Depression of English Agriculture 1873–1896". In Perry, P. J. (ed.). British Agriculture 1875–1914. London: Methuen. p. 54. ISBN 0-416-75940-8.

- ↑ Howkins, Alun (1991). Reshaping Rural England. A Social History 1850–1925. London: HarperCollins Academic. p. 138. ISBN 0-04-445706-5.

- ↑ Cannadine, David (1992). The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy. London: Pan. p. 92. ISBN 0-330-32188-9.

Further reading

- Acheson, Eric. A gentry community: Leicestershire in the fifteenth century, c. 1422-c. 1485 (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Butler, Joan. Landed Gentry (1954)

- Coss, Peter R. The origins of the English gentry (2005) online

- Heal, Felicity. The gentry in England and Wales, 1500-1700 (1994) online.

- Mingay, Gordon E. The Gentry: The Rise and Fall of a Ruling Class (1976) online

- O'Hart, John. The Irish And Anglo-Irish Landed Gentry, When Cromwell Came to Ireland: or, a Supplement to Irish Pedigrees (2 vols) (reprinted 2007)

- Sayer, M. J. English Nobility: The Gentry, the Heralds and the Continental Context (Norwich, 1979)

- Wallis, Patrick, and Cliff Webb. "The education and training of gentry sons in early modern England." Social History 36.1 (2011): 36–53. online

External links

- European Landowners' Organization Archived 25 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine