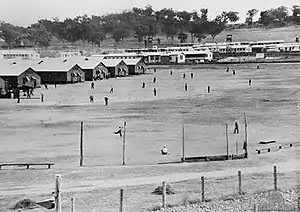

Cowra POW Camp, 1 July 1944. Japanese POWs practising baseball near their quarters, several weeks before the Cowra breakout. The photograph was taken for the Allied Far Eastern Liaison Office, with the intention of using it in propaganda leaflets, to be dropped over Japanese held islands and Japan itself. | |

| Date | 5 August 1944 |

|---|---|

| Location | Near Cowra, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°48′41″S 148°42′14″E / 33.81139°S 148.70389°E |

| Outcome | ~359 Japanese POWs escape |

| Deaths | 235 |

The Cowra breakout occurred on 5 August 1944, when 1,104 Japanese prisoners of war attempted to escape from a prisoner of war camp near Cowra, in New South Wales, Australia. It was the largest prison escape of World War II, as well as one of the bloodiest. During the escape and ensuing manhunt, four Australian soldiers were killed and 231 Japanese soldiers were killed or committed suicide. The remaining escapees were re-captured and imprisoned.

Location and background

Situated some 314 km (195 mi) due west of Sydney, Cowra was the town nearest to No. 12 Prisoner of War Compound, a major POW camp where 4,000 Axis military personnel and civilians were detained throughout World War II. The prisoners at Cowra also included 2,000 Italians, Koreans and Taiwanese (who had served in the Japanese military) as well as Indonesian civilians, detained at the request of the Dutch East Indies government.[1]

By August 1944, there were 2,223 Japanese POWs in Australia, including 544 merchant seamen. There were also 14,720 Italian prisoners, the majority of whom had been captured in the North African Campaign, as well as 1,585 Germans, most of whom were captured naval or merchant seamen.

Although the POWs were treated in accordance with the 1929 Geneva Convention, relations between the Japanese POWs and the guards were poor, due largely to significant cultural differences.[2] A riot by Japanese POWs at Featherston prisoner of war camp in New Zealand, in February 1943, led to security being tightened at Cowra.

Eventually the camp authorities installed several Vickers and Lewis machine guns to augment the rifles carried by the members of the Australian Militia's 22nd Garrison Battalion, which was composed mostly of old or disabled veterans or young men considered physically unfit for front-line service.

Breakout

In the first week of August 1944, a tip-off from an informer (recorded in some sources to be a Korean informant using the name Matsumoto)[3] at Cowra led authorities to plan to move all Japanese POWs at Cowra, except officers and NCOs, to another camp at Hay, New South Wales, some 400 km (250 mi) to the west. The Japanese were notified of the move on 4 August.

In the words of historian Gavin Long, the following night:

At about 2 a.m. a Japanese inmate ran to the camp gates and shouted what seemed to be a warning to the sentries. Then a Japanese bugle sounded. A sentry fired a warning shot. More sentries fired as three mobs of prisoners, shouting "Banzai", began breaking through the wire, one mob on the northern side, one on the western and one on the southern. They flung themselves across the wire with the help of blankets. They were armed with knives, baseball bats, clubs studded with nails and hooks, wire stilettos and garotting cords.[4]

The bugler, Hajime Toyoshima, had been Australia's first Japanese prisoner of the war.[5] Soon afterwards, prisoners set most of the buildings in the Japanese compound on fire.

Within minutes of the start of the breakout attempt, Privates Benjamin Gower Hardy and Ralph Jones manned the No. 2 Vickers machine-gun and began firing into the first wave of escapees. They were soon overwhelmed by a wave of Japanese prisoners who had breached the lines of barbed wire fences. Before dying, Private Hardy managed to remove and throw away the gun's bolt, rendering the gun useless. This prevented the prisoners from turning the machine gun against the guards.

Some 359 POWs escaped, while some others attempted or committed suicide, or were killed by their countrymen. Some of those who did escape also committed suicide to avoid recapture. All the survivors were recaptured within 10 days of their breakout.[6]

Aftermath

During the escape and subsequent round-up of POWs, four Australian soldiers and 231 Japanese soldiers were killed and 108 prisoners were wounded. The leaders of the breakout ordered the escapees not to attack Australian civilians, and none were killed or injured.

The government conducted an official inquiry into the events. Its conclusions were read to the Australian House of Representatives by Prime Minister John Curtin on 8 September 1944. Among the findings were:

- Conditions at the camp were in accordance with the Geneva Conventions;

- No complaints regarding treatment had been made by or on behalf of the Japanese before the incident, which appeared to have been the result of a premeditated and concerted plan;

- The actions of the Australian garrison in resisting the attack averted a greater loss of life, and firing ceased as soon as they regained control;

- Many of the dead had committed suicide or been killed by other prisoners, and many of the Japanese wounded had suffered self-inflicted wounds.

Privates Hardy and Jones were posthumously awarded the George Cross as a result of their actions.

A fifth Australian, Thomas Roy Hancock of C Company 26 Battalion V.D.C. was accidentally shot by another volunteer while dismounting from a vehicle, in the process of deploying to protect railways and bridges from the escapees. Hancock later died of sepsis.

Australia continued to operate No. 12 Camp until the last Japanese and Italian prisoners were repatriated in 1947.

Cowra maintains a significant Japanese war cemetery, the only such cemetery in Australia. In addition, the nearby Cowra Japanese Garden and Cultural Centre, a commemorative Japanese garden, was later built on Bellevue Hill to memorialize these events. The garden was designed by Ken Nakajima in the style of the Edo period.[7]

The last survivor of the breakout attempt, Teruo Murakami, died in Japan on September 14 2023.[8]

Depictions in film and literature

- Dead Men Rising, (1951), Angus & Robertson, (ISBN 0-207-12654-2): a novel by Seaforth Mackenzie, who was stationed at Cowra during the breakout.[9]

- The Night of a Thousand Suicides, (1970), Angus & Robertson, (ISBN 0-207-12741-7): a novel by Teruhiko Asada, translated by Ray Cowan.

- Die like the Carp: The Story of the Greatest Prison Escape Ever, (1978), Corgi Books, ISBN 0-7269-3243-4): a non-fiction book by Harry Gordon.[10]

- The Cowra Breakout (1984): a critically acclaimed 4½-hour television miniseries, written by Margaret Kelly and Chris Noonan, and directed by Noonan and Phillip Noyce.[11][12]

- Voyage from Shame: The Cowra Breakout and Afterwards, (1994), University of Queensland Press, (ISBN 0-7022-2628-9): a non-fiction book by Harry Gordon.[13]

- Lost Officer (2005) ロスト・オフィサー, Spice, (ISBN 4-902835-06-1): a non-fiction book by Dr. Mami Yamada focusing on Japanese officer POWs held in the D compound of the Cowra camp and their involvement in the breakout.

- On That Day, Our Lives Were Lighter Than Toilet Paper: The Great Cowra Breakout (English translation) あの日、僕らの命はトイレットペーパーよりも軽かった -カウラ捕虜収容所からの大脱走 (2008): a 2-hour TV-movie produced by Nippon Television as a 55th-anniversary special.

- Broken Sun (2008): an Australian film directed by Brad Haynes.

- Shame and the Captives (2013), Sceptre, (ISBN 978-1-444-78127-4): a novel by Thomas Keneally.

- Reconsidering the Cowra Breakout of 1944: From the Viewpoints of Survived Japanese Prisoners of War and Their 'Everyday Lives' in the Camp (2014): a doctoral thesis (Japanese language) by Dr. Mami Yamada.

- Barbed Wire and Cherry Blossoms (2016), Simon & Schuster Australia, (ISBN 9781925184846): an historical fiction by Dr Anita Heiss based on an escapee who hid in the nearby Aboriginal mission until the end of the war.

- The Cowra Breakout, (2022), Hachette Australia, (ISBN 9780733647628): a non-fiction book by Mat McLachlan.

See also

References

- ↑ "The Story of Italians at the POW Camp". Cowra Council. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "They had to remember they were soldiers, albeit female | Australian War Memorial". www.awm.gov.au. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ Ota Y. https://mro.massey.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10179/4778/02_whole.pdf - Shooting and Friendship over Japanese Prisoners of War

- ↑ Long, Gavin (1963). "Appendix 5 – The Prison Break at Cowra, August 1944" (PDF). The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Vol. 7. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 623–624. OCLC 1297619.

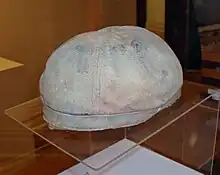

- ↑ S Thompson. Exhibit - Objects through Time: COWRA bugle, c1930s Archived 5 August 2012 at archive.today, Migration Heritage Centre, New South Wales, 2006

- ↑ Wendy Lewis, Simon Balderstone and John Bowan (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. pp. 175–179. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

- ↑ Tam, Tracy, "Australian town commemorates 1944 POW camp breakout", The Japan Times, (Kyodo News), 19 August 2014

- ↑ "Vale Teruo Murakami, the last survivor of the Cowra Breakout". www.cowracouncil.com.au. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ↑ Dead men rising / [by] Kenneth Seaforth Mackenzie. A & R paperback. National Library of Australia. 1973. ISBN 9780207126543.

- ↑ Die like the carp : the story of the greatest prison escape ever / Harry Gordon. National Library of Australia. 1978. ISBN 9780726932434.

- ↑ "The Cowra Breakout - Curator's notes + clips & credits". National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA). Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "The Cowra Breakout (TV mini-series 1984)". IMDb. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ Voyage from shame / [by] Harry Gordon. University of Queensland. National Library of Australia. 1994. ISBN 0702226289.

External links

- "The Cowra Breakout" David Hobson in World War II 1939–45 (Published by) the ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee (Qld) Incorporated. (1998)

- "Official Cowra Japanese Garden Home Page"

- Gavin Long, "The prison breakout at Cowra, August 1944", in Australia in the War of 1939–1945, (Published by) the Australian War Memorial. (1963)

- Wal McKenzie, "Memories of the Cowra Breakout" (no date)

- "Uprisings remembered" S. Muthiah, in The Hindu (Indian national newspaper). (13 February 2005)

- "Fact Sheet 198: Cowra outbreak, 1944" National Archives of Australia. (2000)

- Japan Times, "Ghosts of Cowra breakout haunt Japan to this day"