| United States | |

|---|---|

| Crime rates* (2020) | |

| Violent crimes | |

| Homicide | 6.5 |

| Rape | 38.4 |

| Robbery | 73.9 |

| Aggravated assault | 279.7 |

| Total violent crime | 398.5 |

| Property crimes | |

| Burglary | 314.2 |

| Larceny-theft | 1,398 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 246 |

| Total property crime | 1,958.2 |

Notes *Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. Estimated total population: 329,500,000. In 2013 the FBI modified the definition of rape. Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer | |

Crime has been recorded in the United States since its founding and has fluctuated significantly over time, with a sharp rise after 1900 and reaching a broad bulging peak between the 1970s and early 1990s. After 1992, crime rates have generally trended downwards each year, with the exceptions of a slight increase in property crimes in 2001 and increases in violent crimes in 2005-2006, 2014-2016 and 2020-2021.[1] While official federal crime data beginning in 2021 has a wide margin of error due to the incomplete adoption of the National Incident-Based Reporting System by government agencies, federal data for 2020-2021 and limited data from select U.S. cities collected by the nonpartisan Council on Criminal Justice showed significantly elevated rates of homicide and motor vehicle theft in 2020-2022.[1][2][3] Although overall crime rates have fallen far below the peak of crime seen in the United States during the late 1980s and early 1990s,[4][5] the homicide rate in the U.S. has remained high, relative to other "high income"/developed nations, with eight major U.S. cities ranked among the 50 cities with the highest homicide rate in the world in 2022. The aggregate cost of crime in the United States is significant, with an estimated value of $4.9 trillion reported in 2021.[6] Data from the first half of 2023, from government and private sector sources show that the murder rate has dropped, as much as 12% in as many as 90 cities across the United States.[7] The drop in homicide rates is not uniform across the country however, with some cities such as Memphis, TN, showing an uptick in murder rates.[7]

Statistics on specific crimes are indexed in the annual Uniform Crime Reports by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and by annual National Crime Victimization Surveys by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In addition to the primary Uniform Crime Report known as Crime in the United States, the FBI publishes annual reports on the status of law enforcement in the United States. The report's definitions of specific crimes are considered standard by many American law enforcement agencies. According to the FBI, index crime in the United States includes violent crime and property crime. Violent crime consists of five criminal offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, and gang violence; property crime consists of burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft, and arson.

The basic aspect of a crime considers the offender, the victim, type of crime, severity and level, and location. These are the basic questions asked by law enforcement when first investigating any situation. This information is formatted into a government record by a police arrest report, also known as an incident report. These forms lay out all the information needed to put the crime in the system and it provides a strong outline for further law enforcement agents to review. Society has a strong misconception about crime rates due to media aspects heightening their fear factor.[8] The system's crime data fluctuates by crime depending on certain influencing social factors such as economics, the dark figure of crime, population, and geography.[8]

Crime over time

In the long term, violent crime in the United States has been in decline since colonial times. The homicide rate has been estimated to be over 30 per 100,000 people in 1700, dropping to under 20 by 1800, and to under 10 by 1900.[9]

After World War II, crime rates increased in the United States, peaking from the 1970s to the early-1990s. Violent crime nearly quadrupled between 1960 and its peak in 1991. Property crime more than doubled over the same period. Since the 1990s, however, contrary to common misconception,[10] crime in the United States has declined steadily, and has significantly declined by the late 1990s and also in the early 2000s. Several theories have been proposed to explain this decline:

- The lead–crime hypothesis suggests reduced lead exposure as the cause; Scholar Mark A.R. Kleiman writes: "Given the decrease in lead exposure among children since the 1980s and the estimated effects of lead on crime, reduced lead exposure could easily explain a very large proportion—certainly more than half—of the crime decrease of the 1994–2004 period. A careful statistical study relating local changes in lead exposure to local crime rates estimates the fraction of the crime decline due to lead reduction as greater than 90 percent.[11]

- The number of police officers hired and employed to various police forces increased considerably in the 1990s.[12]

- On September 16, 1994, President Bill Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act into law. Under the act, over $30 billion in federal aid was spent over a six-year period to improve state and local law enforcement, prisons and crime prevention programs. Proponents of the law, including the President, touted it as a lead contributor to the sharp drop in crime which occurred throughout the 1990s, while critics have dismissed it as an unprecedented federal boondoggle.[13]

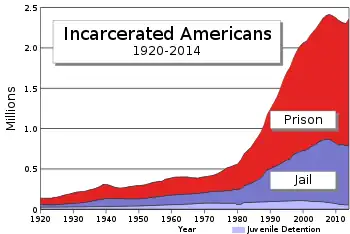

Total incarceration in the United States by year

Total incarceration in the United States by year - The prison population has rapidly increased since the mid-1970s.[12]

- Starting in the mid-1980s, the crack-cocaine market grew rapidly before declining again a decade later. Some authors have pointed towards the link between violent crimes and crack use.[12]

- Legalized abortion reduced the number of children born to mothers in difficult circumstances, and a difficult childhood makes children more likely to become criminals.[14]

- The changing demographics of an aging population has been cited for the drop in overall crime.[15]

- Rising income[16]

- The introduction of the data-driven policing practice CompStat significantly reduced crimes in cities that adopted it.[16]

- The quality and extent of use of security technology both increased around the time of the crime decline, after which the rate of car theft declined; this may have caused rates of other crimes to decline as well.[17]

- Increased rates of immigration to the United States[18][19]

Violent crime rates (per 100,000) in the United States (1960-2018):[20][21]

| Year | Violent crime | Murder and non-negligent manslaughter | Rape | Robbery | Aggravated assault |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 160.9 | 5.1 | 9.6 | 60.1 | 86.1 |

| 1961 | 158.1 | 4.8 | 9.4 | 58.3 | 85.7 |

| 1962 | 162.3 | 4.6 | 9.4 | 59.7 | 88.6 |

| 1963 | 168.2 | 4.6 | 9.4 | 61.8 | 92.4 |

| 1964 | 190.6 | 4.9 | 11.2 | 68.2 | 106.2 |

| 1965 | 200.2 | 5.1 | 12.1 | 71.7 | 111.3 |

| 1966 | 220.0 | 5.6 | 13.2 | 80.8 | 120.3 |

| 1967 | 253.2 | 6.2 | 14.0 | 102.8 | 130.2 |

| 1968 | 298.4 | 6.9 | 15.9 | 131.8 | 143.8 |

| 1969 | 328.7 | 7.3 | 18.5 | 148.4 | 154.5 |

| 1970 | 363.5 | 7.9 | 18.7 | 172.1 | 164.8 |

| 1971 | 396.0 | 8.6 | 20.5 | 188.0 | 178.8 |

| 1972 | 401.0 | 9.0 | 22.5 | 180.7 | 188.8 |

| 1973 | 417.4 | 9.4 | 24.5 | 183.1 | 200.5 |

| 1974 | 461.1 | 9.8 | 26.2 | 209.3 | 215.8 |

| 1975 | 487.8 | 9.6 | 26.3 | 220.8 | 231.1 |

| 1976 | 467.8 | 8.7 | 26.6 | 199.3 | 233.2 |

| 1977 | 475.9 | 8.8 | 29.4 | 190.7 | 247.0 |

| 1978 | 497.8 | 9.0 | 31.0 | 195.8 | 262.1 |

| 1979 | 548.9 | 9.8 | 34.7 | 218.4 | 286.0 |

| 1980 | 596.6 | 10.2 | 36.8 | 251.1 | 298.5 |

| 1981 | 594.3 | 9.8 | 36.0 | 258.4 | 289.3 |

| 1982 | 570.8 | 9.1 | 34.0 | 238.8 | 289.0 |

| 1983 | 537.7 | 8.3 | 33.8 | 216.7 | 279.4 |

| 1984 | 539.9 | 7.9 | 35.7 | 205.7 | 290.6 |

| 1985 | 556.6 | 8.0 | 36.8 | 209.3 | 304.0 |

| 1986 | 620.1 | 8.6 | 38.1 | 226.0 | 347.4 |

| 1987 | 612.5 | 8.3 | 37.6 | 213.7 | 352.9 |

| 1988 | 640.6 | 8.5 | 37.8 | 222.1 | 372.2 |

| 1989 | 666.9 | 8.7 | 38.3 | 234.3 | 385.6 |

| 1990 | 729.6 | 9.4 | 41.1 | 256.3 | 422.9 |

| 1991 | 758.2 | 9.8 | 42.3 | 272.7 | 433.4 |

| 1992 | 757.7 | 9.3 | 42.8 | 263.7 | 441.9 |

| 1993 | 747.1 | 9.5 | 41.1 | 256.0 | 440.5 |

| 1994 | 713.6 | 9.0 | 39.3 | 237.8 | 427.6 |

| 1995 | 684.5 | 8.2 | 37.1 | 220.9 | 418.3 |

| 1996 | 636.6 | 7.4 | 36.3 | 201.9 | 391.0 |

| 1997 | 611.0 | 6.8 | 35.9 | 186.2 | 382.1 |

| 1998 | 567.6 | 6.3 | 34.5 | 165.5 | 361.4 |

| 1999 | 523.0 | 5.7 | 32.8 | 150.1 | 334.3 |

| 2000 | 506.5 | 5.5 | 32.0 | 145.0 | 324.0 |

| 2001 | 504.5 | 5.6 | 31.8 | 148.5 | 318.6 |

| 2002 | 494.4 | 5.6 | 33.1 | 146.1 | 309.5 |

| 2003 | 475.8 | 5.7 | 32.3 | 142.5 | 295.4 |

| 2004 | 463.2 | 5.5 | 32.4 | 136.7 | 288.6 |

| 2005 | 469.0 | 5.6 | 31.8 | 140.8 | 290.8 |

| 2006 | 473.6 | 5.8 | 31.6 | 150.0 | 292.0 |

| 2007 | 471.8 | 5.7 | 30.6 | 148.3 | 287.2 |

| 2008 | 458.6 | 5.4 | 29.8 | 145.9 | 277.5 |

| 2009 | 431.9 | 5.0 | 29.1 | 133.1 | 264.7 |

| 2010 | 404.5 | 4.8 | 27.7 | 119.3 | 252.8 |

| 2011 | 387.1 | 4.7 | 27.0 | 113.9 | 241.5 |

| 2012 | 387.8 | 4.7 | 27.1 | 113.1 | 242.8 |

| 2013 | 369.1 | 4.5 | 25.9 | 109.0 | 229.6 |

| 2014 | 361.6 | 4.4 | 26.6 | 101.3 | 229.2 |

| 2015 | 373.7 | 4.9 | 28.4 | 102.2 | 238.1 |

| 2016 | 386.6 | 5.4 | 30.0 | 102.9 | 248.3 |

| 2017 | 383.8 | 5.3 | 30.7 | 98.6 | 249.2 |

| 2018 | 368.9 | 5.0 | 30.9 | 86.2 | 246.8 |

Property crime rates (per 100,000) in the United States (1960–2018):[20][21]

| Year | Property crime | Burglary | Larceny | Motor vehicle theft |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 1,726.3 | |||

| 1961 | 1,747.9 | |||

| 1963 | 2,012 | |||

| 1965 | 2,249 | |||

| 1967 | 2,736 | |||

| 1969 | 3,351 | |||

| 1971 | 3,769 | |||

| 1973 | 3,737 | |||

| 1975 | 4,811 | |||

| 1977 | 4,602 | |||

| 1979 | 5,017 | |||

| 1981 | 5,264 | |||

| 1983 | 4,637 | |||

| 1985 | 4,650 | |||

| 1987 | 4,940 | |||

| 1989 | 5,078 | |||

| 1991 | 5,140 | |||

| 1992 | 4,903.7 | 1,168.4 | 3,103.6 | 631.6 |

| 1993 | 4,740.0 | 1,099.7 | 3,033.9 | 606.3 |

| 1994 | 4,660.2 | 1,042.1 | 3,026.9 | 591.3 |

| 1995 | 4,590.5 | 987.0 | 3,043.2 | 560.3 |

| 1996 | 4,451.0 | 945.0 | 2,980.3 | 525.7 |

| 1997 | 4,316.3 | 918.8 | 2,891.8 | 505.7 |

| 1998 | 4,052.5 | 863.2 | 2,729.5 | 459.9 |

| 1999 | 3,743.6 | 770.4 | 2,550.7 | 422.5 |

| 2000 | 3,618.3 | 728.8 | 2,477.3 | 412.2 |

| 2001 | 3,658.1 | 741.8 | 2,485.7 | 430.5 |

| 2002 | 3,630.6 | 747.0 | 2,450.7 | 432.9 |

| 2003 | 3,591.2 | 741.0 | 2,416.5 | 433.7 |

| 2004 | 3,514.1 | 730.3 | 2,362.3 | 421.5 |

| 2005 | 3,431.5 | 726.9 | 2,287.8 | 416.8 |

| 2006 | 3,346.6 | 733.1 | 2,213.2 | 400.2 |

| 2007 | 3,276.4 | 726.1 | 2,185.4 | 364.9 |

| 2008 | 3,214.6 | 733.0 | 2,166.1 | 315.4 |

| 2009 | 3,041.3 | 717.7 | 2,064.5 | 259.2 |

| 2010 | 2,945.9 | 701.0 | 2,005.8 | 239.1 |

| 2011 | 2,905.4 | 701.3 | 1,974.1 | 230.0 |

| 2012 | 2,868.0 | 672.2 | 1,965.4 | 230.4 |

| 2013 | 2,733.6 | 610.5 | 1,901.9 | 221.3 |

| 2014 | 2,574.1 | 537.2 | 1,821.5 | 215.4 |

| 2015 | 2,500.5 | 494.7 | 1,783.6 | 222.2 |

| 2016 | 2,451.6 | 468.9 | 1,745.4 | 237.3 |

| 2017 | 2,362.9 | 429.7 | 1,695.5 | 237.7 |

| 2018 | 2,199.5 | 376.0 | 1,594.6 | 228.9 |

Arrests

Each state has a set of statutes enforceable within its own borders. A state has no jurisdiction outside of its borders, even though still in the United States. It must request extradition from the state in which the suspect has fled. In 2014, there were 186,873 misdemeanor suspects outside specific states jurisdiction against whom no extradition would be sought. Philadelphia has about 20,000 of these since it is near a border with four other states. Extradition is estimated to cost a few hundred dollars per case.[22]

Analysis of arrest data from California indicates that the most common causes of felony arrest are for violent offenses such as robbery and assault, property offenses such as burglary and auto theft, and drug offenses. For misdemeanors, the most common causes of arrest were traffic offenses, most notably impaired driving, drug offenses, and failure to appear in court. Other common causes of misdemeanor arrest included assault and battery and minor property offenses such as petty theft.[23]

Arrests by gender

According to the Office Of Justice Programs, crimes like burglary and vandalism have gone down during the past few years for men, and crimes like murder and robbery have gone down for women. For both genders, most of the crimes committed are done by people ages 25 and above.

| Murder | Assault | Robbery | Arson | Burglary | Vandalism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 10,900 | 293,230 | 57,590 | 7,720 | 120,740 | 133,260 |

| 2019 | 9,600 | 295,040 | 62,930 | 7,100 | 136,420 | 138,620 |

| 2018 | 10,520 | 302,600 | 74,650 | 7,280 | 143,570 | 138,120 |

| 2017 | 10,670 | 298,250 | 80,250 | 7,280 | 161,790 | 145,920 |

| 2016 | 10,370 | 294,850 | 82,140 | 7,680 | 168,880 | 152,900 |

| Murder | Assault | Robbery | Arson | Burglary | Vandalism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 1,540 | 87,960 | 10,310 | 2,060 | 28,610 | 40,510 |

| 2019 | 1,460 | 90,230 | 11,620 | 1,960 | 35,170 | 41,880 |

| 2018 | 1,450 | 93,200 | 13,480 | 2,110 | 35,040 | 41,710 |

| 2017 | 1,530 | 90,670 | 13,800 | 1,830 | 37,480 | 42,430 |

| 2016 | 1,420 | 89,120 | 13,620 | 2,130 | 38,440 | 43,050 |

Arrests by age

In 2020, out of the 7,632,470 crimes documented that year, 5,721,190 of them were committed by someone who was at least 25 years of age.[24] 4,225,140 of them being committed by men and 1,496,050 being committed by women.

| 0-17 | 18-20 | 21-24 | 25 and Older | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 424,300 | 592,260 | 894,730 | 5,721,190 |

| 2019 | 684,230 | 804,720 | 1,199,730 | 7,396,530 |

| 2018 | 721,630 | 896,240 | 1,314,940 | 7,378,150 |

| 2017 | 801,310 | 1,015,420 | 1,433,060 | 7,305,200 |

| 2016 | 855,460 | 1,080,580 | 1,546,400 | 7,179,810 |

Influences on crime

Childhood exposure to violence

A 1997 report form the US Department of Justice states that "Most violent behavior is learned behavior. Early exposure to violence in the family may involve witnessing either violence or physical abuse.", with exposure to this violence in childhood linked to an increase in violent behaviour as an adolescent by as much as 40%.[25] Gangs and illegal markets provide high levels of exposure to violence, and violent role models and positive rewards for criminal and violent activity, such as drug distribution. Gangs are more likely to be active in poor, minority and disorganized neighborhoods; which have further effects on violent crime; as in those communities there are usually fewer or limited opportunities for employment and evidence suggests these neighbourhoods inhibit the normal progression of adolescent development.

According to the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting statistics in 2019, juveniles (0-17 years) represented 7.13% of arrests (adults: 92.87%); this is down from 12.65% in 2010, with the total number of arrests of juveniles down by 55.5%; this is explained by the drop in arrests of all ages by 21.0%.[26] When controlled for age1, the rate of juveniles arrests in 2010 was 1,296 per 100,000, and in 2019 was 586 per 100,000. Data shows that total arrests increase ten fold from ages 12-14 and then double roughly every 3 years in age from age 14 reaching a peak by age 19 that remains relatively constant until 35.[27]

Crime type and severity

People are more likely to fear and be less sympathetic toward offenders with a history of violent or sexual crime.[28] Violent criminal history is defined by the FBI as any offense, of a violent felony, including rape, homicide, aggravated assault, and robbery.[29] People tend to express more negative attitude towards violent offenders in comparison to those with a history of non-violent crime, misdemeanors, and no sexual crimes.[28]

NOTES

1. Using Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) statistics, juvenile population in 2010 was 74,122,633, and in 2019 was 73,088,675[30]

Crime victimology

In 2011, surveys indicated more than 5.8 million violent victimizations and 17.1 million property victimizations took place in the United States; according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, each property victimization corresponded to one household, while violent victimizations is the number of victims of a violent crime.[34]

Patterns are found within the victimology of crime in the United States. Overall, people with lower incomes, those younger than 25, and non-whites were more likely to report being the victim of crime.[34] Income, gender, and age had the most dramatic effect on the chances of a person being victimized by crime, while the characteristic of race depended upon the crime being committed.[34]

In terms of gender, the BJS National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) published in 2019 that "the percentage of violent victimizations reported to police was higher for females (46%) than for males (36%)". This difference can largely be attributed to the reporting of simple assaults, as the percentages of violent victimizations reported to police, excluding simple assault, were similar for females (47%) and males (46%). The victim-to-population ratio of 1.0 for both males and females shows that the percentage of violent incidents involving male (49%) or female (51%) victims was equal to males' (49%) or females' (51%) share of the population.[35]

In regards to rape, the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) indicates females are disproportionately more affected than males. According to the data collected from 2010 to 2020, women make 89% of victims of rape, while men make 11%. Perpetrators are 93% men.[36]

Concerning age, those younger than twenty-five were more likely to fall victim to crime, especially violent crime.[37] The chances of being victimized by violent crime decreased far more substantially with age than the chances of becoming the victim of property crime.[37] For example, 3.03% of crimes committed against a young person were theft, while 20% of crimes committed against an elderly person were theft.[37]

Bias motivation reports showed that of the 7,254 hate crimes reported in 2011, 47.7% (3,465) were motivated by race, with 72% (2,494) of race-motivated incidents being anti-black.[38] In addition, 20.8% (1,508) of hate crimes were motivated by sexual orientation, with 57.8% (871) of orientation-motivated incidents being anti-male homosexual.[38]

The third largest motivation factor for hate crime was religion, representing 18.2% (1,318) incidents, with 62.2% (820) of religion-motivated incidents being anti-Jewish.[38]

As of 2007, violent crime against homeless people is increasing.[39]

The likelihood of falling victim to crime relates to both demographic and geographic characteristics.[40]

In 2010, according to the UNODC, 67.5% of all homicides in the United States were perpetrated using a firearm.[41] The costliest crime in terms of total financial impact on all of its victims, and the most underreported crime is rape, in the United States.[42][43]

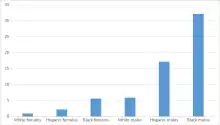

Incarceration

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world (which includes pre-trial detainees and sentenced prisoners).[44] As of 2009, 2.3 million people were incarcerated in the United States, including federal and state prisons and local jails, creating an incarceration rate of 793 persons per 100,000 of national population.[44] During 2011, 1.6 million people were incarcerated under the jurisdiction of federal and state authorities.[45] At the end of 2011, 492 persons per 100,000 U.S. residents were incarcerated in federal and state prisons.[45] Of the 1.6 million state and federal prisoners, nearly 1.4 million people were under state jurisdiction, while 215,000 were under federal jurisdiction.[45] Demographically, nearly 1.5 million prisoners were male, and 115,000 were female, while 581,000 prisoners were black, 516,000 were white, and 350,000 were Hispanic.[45]

Among the 1.35 million sentenced state prisoners in 2011, 725,000 people were incarcerated for violent crimes, 250,000 were incarcerated for property crimes, 237,000 people were incarcerated for drug crimes, and 150,000 were incarcerated for other offenses.[45] Of the 200,000 sentenced federal prisoners in 2011, 95,000 were incarcerated for drug crimes, 69,000 were incarcerated for public order offenses, 15,000 were incarcerated for violent crimes, and 11,000 were incarcerated for property crimes.[45]

International comparison

The manner in which the United States' crime rate compares to other countries of similar wealth and development depends on the nature of the crime used in the comparison.[46] Overall crime statistic comparisons are difficult to conduct, as the definition and categorization of crimes varies across countries. Thus an agency in a foreign country may include crimes in its annual reports which the U.S. omits, and vice versa.

However, some countries such as Canada have similar definitions of what constitutes a violent crime, and nearly all countries had the same definition of the characteristics that constitutes a homicide. Overall the total crime rate of the United States is higher than developed countries, specifically Europe and East Asia, with South American countries and Russia being the exceptions.[47] Some types of reported property crime in the U.S. survey as lower than in Germany or Canada, yet the homicide rate in the United States is substantially higher as is the prison population.

The difference in homicide rate between the U.S. and other high income countries has widened in recent years especially since the 30% rise in 2020 was not replicated elsewhere, and is also above many developing countries such as China, India and Turkey.[48] In the European Union, homicides fell 32% between 2008-2019 to 3,875[49] while rising by 4,901 in the U.S. in 2020 alone,[50] leaving the U.S. with a homicide rate 7x higher. In reputable estimates of crime across the globe, the U.S. generally ranks slightly below the middle, roughly 70th lowest or 100th highest.[51][52]

Violent crime

The reported U.S. violent crime rate includes murder, rape and sexual assault, robbery, and assault,[53] whereas the Canadian violent crime rate includes all categories of assault, including Assault level 1 (i.e., assault not using a weapon and not resulting in serious bodily harm).[54][55] A Canadian government study concluded that direct comparison of the two countries' violent crime totals or rates was "inappropriate".[56]

France does not count minor violence such as punching or slapping as assault, whereas Austria, Germany, Finland and the United Kingdom do count such occurrences.[57]

The United Kingdom similarly has different definitions of what constitutes violent crime compared to the United States, making a direct comparison of the overall figure flawed. The FBI's Uniform Crime Reports defines a "violent crime" as one of four specific offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. The British Home Office, by contrast, has a different definition of violent crime, including all "crimes against the person", including simple assaults, all robberies, and all "sexual offenses", as opposed to the FBI, which only counts aggravated assaults and "forcible rapes".[58]

Crime rates are necessarily altered by averaging neighborhood higher or lower local rates over a larger population which includes the entire city. Having small pockets of dense crime may increase a city's average crime rate. It is estimated that violent crime accounts for as much as $2.2 trillion by the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, accounting for about 85% of the total cost of crime in the United States.[59]

| Country | Homicide | Rape | Sexual assault | Robbery | Assault |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 1.0 (0.8) 2022 * | — † | 123.7 2022 [61]† | 36.75 2022 | 1017.6# 2022 |

| Germany | 0.8 | 9.4 2010 | 56.9 2010 | 60 | 630 |

| England/Wales | 1.1 | 28.8 2010 | 82.1 2010 | 137 | 730 |

| Scotland | 1.6 | 17.0 2009 | 124.6 2009 | 48 | 1487 |

| United States | 5.0 | 44.4 2018 UCR[64] | 270.0 2018 NCVS[65]^ | 133 | 241 |

| Sweden | 1.0 | 63.5 2010 | 183.0 2010 | 103 | 927 |

*Australian homicide statistics include murder, and manslaughter (attempted murder is excluded). Murder rate in brackets.

†Australian statistics record only sexual assault, and do not have separate statistics for rape only. Sexual assault is defined to include rape, attempted rape, aggravated sexual assault (assault with a weapon), indecent assault, penetration by objects, forced sexual activity that did not end in penetration and attempts to force a person into sexual activity; but excludes unwanted sexual touching. [66]

#Australian assault statistics calculated using per state/territory statistics, excluding Victoria as assault data is not collected.[61]

^UCR rape statistics do NOT include sexual assault, while the NCVS does, furthermore NCVS define sexual assault to include as well sexual touching with/without force, and verbal threats of rape or sexual assault, as well as rape, attempted rape, and sexual assault that isn't rape.[62][63]

Homicide

According to a 2013 report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), between 2005 and 2012, the average homicide rate in the U.S. was 4.9 per 100,000 inhabitants compared to the average rate globally, which was 6.2. However, the U.S. had much higher murder rates compared to four other selected "developed countries", which all had average homicide rates of 0.8 per 100,000.[47] In 2004, there were 5.5 homicides for every 100,000 persons, roughly three times as high as Canada (1.9) and six times as high as Germany and Italy (0.9).[68][54]

In 2018, the US murder rate was 5.0 per 100,000, for a total of 15,498 murders.[69]

| Country | Singapore | Iceland | Armenia | United States | Moldova | South Sudan | Panama |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homicide rate (per hundred thousand) (international methodology)[47] | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 12 | 53.1 |

In the United States, the number of homicides where the victim and offender relationship was undetermined has been increasing since 1999 but has not reached the levels experienced in the early 1990s. In 14% of all murders, the victim and the offender were strangers. Spouses and family members made up about 15% of all victims, about one-third of the victims were acquaintances of the assailant, and the victim and offender relationship was undetermined in over one-third of homicides. Gun involvement in homicides were gang-related homicides which increased after 1980, homicides that occurred during the commission of a felony which increased from 55% in 1985 to 77% in 2005, homicides resulting from arguments which declined to the lowest levels recorded recently, and homicides resulting from other circumstances which remained relatively constant. Because gang killing has become a normal part of inner cities, many including police hold preconceptions about the causes of death in inner cities. When a death is labeled gang-related it lowers the chances that it will be investigated and increases the chances that the perpetrator will remain at large. In addition, victims of gang killings often determine the priority a case will be given by police. Jenkins (1988) argues that many serial murder cases remain unknown to police and that cases involving Black offenders and victims are especially likely to escape official attention.[70]

According to the FBI, "When the race of the offender was known, 53.0 percent were black, 44.7 percent were white, and 2.3 percent were of other races. The race was unknown for 4,132 offenders. (Based on Expanded Homicide Data Table 3). Of the offenders for whom gender was known, 88.2 percent were male."[71] According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, from 1980 to 2008, 84 percent of white homicide victims were killed by white offenders and 93 percent of black homicide victims were killed by black offenders.[32]

Gun violence

The United States has the highest rate of civilian gun ownership per capita.[72][73][74] According to the CDC, between 1999 and 2014 there were 185,718 homicides from use of a firearm and 291,571 suicides using a firearm.[75] The U.S. gun homicide rate in 2019 was 18 times the average rate in other developed countries.[76] Despite a significant increase in the sales of firearms since 1994, the US has seen a drop in the annual rate of homicides using a firearm from 7.0 per 100,000 population in 1993 to 3.6 per 100,000 in 2013.[77] In the ten years between 2000 and 2009, the ATF reported 37,372,713 clearances for purchase, however, in the four years between 2010 and 2013, the ATF reported 31,421,528 clearances.[78]

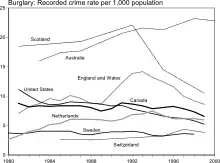

Property crime

According to a 2004 study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, looking at the period from 1981 to 1999, the United States had a lower surveyed residential burglary rate in 1998 than Scotland, England, Canada, the Netherlands, and Australia. The other two countries included in the study, Sweden and Switzerland, had only slightly lower burglary rates. For the first nine years of the study period the same surveys of the public showed only Australia with rates higher than the United States. The authors noted various problems in doing the comparisons including infrequent data points. (The United States performed five surveys from 1995 to 1999 when its rate dipped below Canada's, while Canada ran a single telephone survey during that period for comparison.)[46]

Crimes against children

Violence against children from birth to adolescence is considered a "global phenomenon that takes many forms (physical, sexual, emotional), and occurs in many settings, including the home, school, community, care, and justice systems, and over the Internet."[79]

According to a 2001 report from UNICEF, the United States has the highest rate of deaths from child abuse and neglect of any industrialized nation, at 2.4 per 100,000 children; France has 1.4, Japan 1, UK 0.9 and Germany 0.8. According to the US Department of Health, the state of Texas has the highest death rate, at 4.1 per 100,000 children, New York has 2.5, Oregon 1.5 and New Hampshire 0.4. [80] A 2018 report from the Congressional Research Service stated, at the national level, violent crime and homicide rates have increased each year from 2014 to 2016.[81]

In 2016, data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) revealed that approximately 1,750 children died from either abuse or neglect; further, this is a continuing trend with an increasing 7.4% of crimes against children from 2012 to 2016 and these statistics can be compared to a rate of 2.36 children per 100,000 children in the United States general population.[82] In addition, 44.2% of these 2016 statistics are specific to physical abuse towards a child.[82]

A 2016 report from the Child Welfare Information Gateway also showed that parents account for 78% of violence against children in the United States.[83]

Human trafficking

Human trafficking is categorized into the following three groups: (1) sex trafficking; (2) sex and labor trafficking; and (3) labor trafficking; In addition, the rate of domestic minor sex trafficking has exponentially increased over the years. Sex trafficking of children also referred to as commercial sexual exploitation of children, is categorized by the following forms: pornography, prostitution, child sex tourism, and child marriage. Profiles of traffickers and types of trafficking differ in the way victims are abducted, how they are treated, and the reason for the abduction.

According to a 2017 report from the National Human Trafficking Hotline (NHTH), out of 10,615 reported survivors of sex trafficking, 2,762 of those survivors were minors.[84]

The U.S. Department of Justice defines Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children (CSEC) as a range of crimes and activities involving the sexual abuse or exploitation of a child for the financial benefit of any person or in exchange for anything of value (including monetary and non-monetary benefits) given or received by any person. These crimes against children, which may occur at any time or place, rob them of their childhood and are extremely detrimental to their emotional and psychological development.[85]

Types of human sex trafficking

In pimp-controlled trafficking, the pimp typically is the only trafficker involved who has full physical, psychological and emotional control over the victim. In gang-controlled trafficking, a large group of people has power over the victim, forcing the victim to take part in illegal or violent tasks for the purpose of obtaining drugs. Another form is called Familial trafficking, which differs the most from the two mentioned above because the victim is typically not abducted. Instead, the victim is forced into being sexually exploited by family members in exchange for something of monetary value, whether that's paying back debt, or obtaining drugs or money. This type of sexual exploitation tends to be the most difficult to detect, yet remains as the most prevalent form of human sex trafficking within the United States.[85]

In 2009, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention reported that the average age when children first fall victim to CSEC is between ages 12 and 14. However, this age has become increasingly younger due to exploiters' fear of contracting HIV or AIDS from older victims.[85]

In 2018, the Office of Public Affairs within the Department of Justice released a report from operation "Broken Heart" conducted by Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) task forces, stating that more than 2,300 suspected online child sex offenders were arrested on the following allegations:[86]

- produce, distribute, receive and possess child pornography

- engage in online enticement of children for sexual purposes

- engage in the sex trafficking of children

- travel across state lines or to foreign countries and sexually abuse children

In addition, a 2011 report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics described the characteristics of suspected human trafficking incidents, identifying roughly 95% of victims as female and over half as 17 years old or younger.

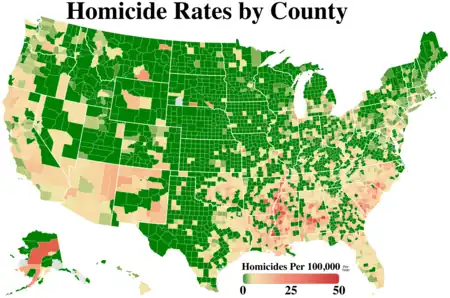

Geography of crime

Crime rates vary in the United States depending on the type of community.[87] Within metropolitan statistical areas, both violent and property crime rates are higher than the national average; in cities located outside metropolitan areas, violent crime was lower than the national average, while property crime was higher.[87] For rural areas, both property and violent crime rates were lower than the national average.[87]

Regions

For regional comparisons, the FBI divides the United States into four regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West.[88] For 2019, the region with the lowest violent crime rate was the Northeast, with a rate of 292.4 per 100,000 residents, while the region with the highest violent crime rate was the West, with a rate of 413.5 per 100,000.[88] For 2019, the region with the lowest property crime rate was the Northeast, with a rate of 1,350.4 per 100,000 residents, while the region with the highest property crime rate was the West, with a rate of 2,411.7 per 100,000.[88]

States

Crime rates vary among U.S. states.[89] In 2019, the state with the lowest violent crime rate was Maine, with a rate of 115.2 per 100,000 residents, while the state with the highest violent crime rate was Alaska, with a rate of 867.1 per 100,000.[89] However, the District of Columbia, the U.S. capital district, had a violent crime rate of 1,049.0 per 100,000 in 2019.[89] In 2019, the state with the highest property crime rate was Louisiana, with a rate of 3,162.0 per 100,000, while the state with the lowest property crime rate was Massachusetts, with a rate of 1,179.8 per 100,000.[89] However, Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States, had a property crime rate of 702.7 per 100,000 in 2011.[89] According to 2022 FBI Uniform Crime Report, Louisiana's murder rate of 16.1 per 100,000 residents was the highest in the nation (states) for the 34th straight year.[90]

Metropolitan areas

Crime in metropolitan statistical areas tends to be above the national average; however, wide variance exists among and within metropolitan areas.[91] Some responding jurisdictions report very low crime rates, while others have considerably higher rates; these variations are due to many factors beyond population.[91] FBI crime statistics publications strongly caution against comparison rankings of cities, counties, metropolitan statistical areas, and other reporting units without considering factors other than simply population.[91] For 2017, the metropolitan statistical area with the highest violent crime rate was the Memphis, Tennessee, metropolitan area, with a rate of 1168.3 per 100,000 residents, while the metropolitan statistical area with the lowest violent crime rate was Bangor, Maine, metropolitan area, with a rate of 65.8.[92]

According to Jeffrey Ross, isolated, underserved urban communities tend to perpetuate criminality and gang violence. In the United States, it is common for crime to be concentrated in a small number of economically disadvantaged areas, which may remain persistently afflicted by crime no matter which ethnic group is living there.[93]

| Metropolitan statistical area | Violent crime rate (per 100,000) | Property crime rate (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA MSA | 367.6 | 2,865.7 |

| Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA-NH MSA | 305.3 | 1,308.5 |

| Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI MSA | —[lower-alpha 1] | 2,024.6 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX MSA | 369.3 | —[lower-alpha 2] |

| Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land, TX MSA | 593.1 | —[lower-alpha 3] |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA MSA | 496.7 | 2,350.3 |

| Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach, FL MSA | 458.2 | 3,076.4 |

| New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA MSA | 332.9 | 1,335.6 |

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD MSA | 428.7 | 2,055.6 |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV MSA | 273.4 | 1,745.4 |

Number and growth of criminal laws

There are conflicting opinions on the number of federal crimes,[94][95] but many have argued that there has been explosive growth and it has become overwhelming.[96][97][98] In 1982, the U.S. Justice Department could not come up with a number, but estimated 3,000 crimes in the United States Code.[94][95][99] In 1998, the American Bar Association (ABA) said that it was likely much higher than 3,000, but didn't give a specific estimate.[94][95] In 2008, the Heritage Foundation published a report that put the number at a minimum of 4,450.[95] When staff for a task force of the U.S. House Judiciary Committee asked the Congressional Research Service (CRS) to update its 2008 calculation of criminal offenses in the United States Code in 2013, the CRS responded that they lack the staffing and resources to accomplish the task.[100]

See also

- Corruption in the United States

- Gangs in the United States

- Illegal drug trade in the United States

- Incarceration in the United States

- Mass shootings in the United States

- Race and crime in the United States

- National Crime Information Center Interstate Identification Index

- United States cities by crime rate

- List of U.S. states and territories by violent crime rate

- List of U.S. states and territories by intentional homicide rate

- Strict liability (criminal) § United States

- Contempt of court § United States

- List of criminal enterprises, gangs and syndicates § United States

- Illegal immigration to the United States and crime

- Terrorism in the United States

Notes

- ↑ "The FBI determined that the agency's data were overreported for some parts of the metro area."[92] And some agency(s) "submitted rape data classified according to the legacy UCR definition."[92]

- ↑ "The FBI determined that the agency's data were overreported for some parts of the metro area."[92]

- ↑ "The FBI determined that the agency's data were underreported for some parts of the metro area."[92]

References

- 1 2 "Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer". FBI. 26 September 2022. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- ↑ "Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in U.S. Cities Year-End 2021 Update". Council on Criminal Justice. 24 January 2022. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- ↑ "Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in U.S. Cities Year-End 2022 Update" (PDF). Council on Criminal Justice. 25 January 2023.

- ↑ Beckett, Beckett; Clayton, Abené (June 30, 2021). "How bad is the rise in US homicides? Factchecking the 'crime wave' narrative police are pushing". The Guardian. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ↑ Graham, David A. (September 29, 2021). "America Is Having a Violence Wave, Not a Crime Wave". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ↑ Anderson, David A. (November 2021). "The Aggregate Cost of Crime in the United States". Journal of Law and Economics. 64 (4): 857–885. doi:10.1086/715713. S2CID 246635242. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- 1 2 "The Murder Rate is Suddenly Falling". The Atlantic. 5 June 2023.

- 1 2 "The measurement and prevalence of violent crime in the United States: persons, places, and times".

- ↑ Fischer, Claude (16 June 2010). "A crime puzzle: Violent crime declines in America". UC Regents. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ↑ "5 facts about crime in the U.S." Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ↑ When Brute Force Fails: How to Have Less Crime and Less Punishment, Princeton University Press 2009 p. 133 citing Richard Nevin, "How Lead Exposure Relates to Temoral Changes in IQ, Violent Crime and Unwed Pregnancy". Environmental Research 83, 1 (2000): 1–22.

- 1 2 3 Levitt, Steven D. (2004). "Understanding Why Crime Fell in the 1990s: Four Factors that Explain the Decline and Six that Do Not" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 18 (1): 163–190. doi:10.1257/089533004773563485. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 12, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ↑ Lehman, Jeffrey; Phelps, Shirelle (2005). West's Encyclopedia of American Law, Volume 10 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson/Gale. ISBN 0787663794.

- ↑ Donohue, John; Levitt, Steven (March 1, 2000). "The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime". Berkeley Program in Law & Economics, Working Paper Series. 2000 (2): 69. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- ↑ Von Drehle, David (February 22, 2010). "What's Behind America's Falling Crime Rate". Time. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- 1 2 Roeder, Oliver K.; et al. (February 12, 2015). "What Caused the Crime Decline?". Brennan Center for Justice. SSRN 2566965. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ↑ Farrell, G.; Tseloni, A.; Mailley, J.; Tilley, N. (February 22, 2011). "The Crime Drop and the Security Hypothesis" (PDF). Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 48 (2): 147–175. doi:10.1177/0022427810391539. S2CID 145747130. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ↑ Wadsworth, Tim (June 2010). "Is Immigration Responsible for the Crime Drop? An Assessment of the Influence of Immigration on Changes in Violent Crime Between 1990 and 2000". Social Science Quarterly. 91 (2): 531–553. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00706.x.

- ↑ Sampson, Robert J. (February 2008). "Rethinking crime and immigration". Contexts. 7 (1): 28–33. doi:10.1525/ctx.2008.7.1.28.

- 1 2 "Crime in the US, 1960-2004, Bureau of Justice Statistics". Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- 1 2 "Table 1". FBI. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ↑ Heath, Brad (March 13, 2014). "A license to commit crimes". USA Today. pp. 1B, 4B. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ↑ Lofstrom, Magnus; Martin, Brandon; Goss, Justin; Hayes, Joseph; Raphael, Steven (December 2018). "New Insights into California Arrests" (PDF). Public Policy Institute of California. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ↑ "Arrests by offense, age, and gender". www.ojjdp.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

- ↑ "Environmental Factors Contribute to Juvenile Crime and Violence (From Juvenile Crime: Opposing Viewpoints, P 83-89, 1997, A E Sadler, ed. -- See NCJ-167319) | Office of Justice Programs". www.ojp.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

- ↑ "FBI UCR | Table 32 - Ten-Year Arrest Trends; Totals, 2010–2019". Federal Bureau of Investigation | Uniform Crime Reporting. Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2019. Archived from the original on 2023-08-18. Retrieved 2023-10-15.

- ↑ "FBI UCR | Table 38; Arrests by Age, 2019". Federal Bureau of Investigation | Uniform Crime Reporting. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 2023-10-15.

- 1 2 "Predicting support for community corrections: Crime type and severity, and offender, observer, and victim characteristics".

- ↑ "Table 1". FBI. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ↑ Justice, National Center for Juvenile. "Easy Access to Juvenile Populations: Population Profiles : Table Age and Date 2010, 2019". www.ojjdp.gov. Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- ↑ Lopez, German (December 15, 2022). "Gun Violence and Children / A portrait of an American tragedy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 15, 2022. Data source attribution: "U.S. data is from 2020; data for other countries from 2019. Sources: C.D.C.; IMHE; United Nations." Source's bar chart: original and archive.

- 1 2 Cooper, Alexia D.; Smith, Erica L. (November 16, 2011). Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980–2008 (Report). Bureau of Justice Statistics. p. 11. NCJ 236018. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018.

- ↑ ● Data through 2016: "Guns / Firearm-related deaths". NSC.org copy of U.S. Government (CDC) data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018. (archive of actual data).

● 2017 data: Howard, Jacqueline (December 13, 2018). "Gun deaths in US reach highest level in nearly 40 years, CDC data reveal". CNN. Archived from the original on December 13, 2018. (2017 CDC data)

● 2018 data: "New CDC Data Show 39,740 People Died by Gun Violence in 2018". efsgv.org. January 31, 2020. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. (2018 CDC data)

● 2019-2023 data: "Past Summary Ledgers". Gun Violence Archive. January 2024. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024. - 1 2 3 Bureau of Justice Statistics (October 2012). "Criminal Victimization, 2011" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 19, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Criminal Victimization, 2019". Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- ↑ "Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- 1 2 3 Bureau of Justice Statistics. "Criminal Victimization, 2005". U.S. Department of Justice. Archived from the original on September 26, 2006.

- 1 2 3 "Hate Crime Statistics, Offenders". FBI. 2011. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Lewan, Todd, "Unprovoked Beatings of Homeless Soaring", Associated Press, April 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Criminal Victimization Survey" (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 17, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ Homicides by firearms Archived August 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine UNODC. Retrieved: July 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Statistics". Arkansas Coalition Against Sexual Assault. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ↑ "Rape and Sexual Assault". Medical University of South Carolina. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- 1 2 R. Walmsley (May 2011). "World Prison Population List" (PDF). International Centre for Prison Studies.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bureau of Justice Statistics (December 2012). "Prisoners in 2011" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- 1 2 "National Crime Rates Compared". Archived from the original on November 15, 2006. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- 1 2 3 UNODC (2014). Global Study on Homicide 2013 (PDF). United Nations. ISBN 978-92-1-054205-0. Sales No. 14.IV.1. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ↑ "List of countries by international homicide rate". Wikipedia. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ↑ "Crime statistics". Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ↑ "FBI Data Shows an Unprecedented Spike in Murders Nationwide in 2020". NPR. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ↑ "Vision of Humanity". 24 July 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ↑ "The Legatum Prosperity Index 2021". Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ↑ "Violent Crime". United States Bureau of Justice Statistics. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- 1 2 "BKA, German federal crime statistics 2004 (German)" (PDF). BKA. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ↑ "Crime in Canada, Canada Statistics". Archived from the original on August 6, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ↑ Feasibility Study on Crime Comparisons Between Canada and the United States Archived July 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Maire Gannon, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada, Cat. no. 85F0035XIE, Accessed June 28, 2009

- ↑ European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics Archived September 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine 2010, Fourth edition, English.wodc.nl

- ↑ "By the Numbers: Is the UK really 5 times more violent than the US?". The Skeptical Libertarian. January 12, 2013. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ↑ Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (February 18, 2021). "Yearly Cost of Crime in U.S. $2.6 Trillion: First Estimate in 25 Years". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ↑ "Comparisons of Crime in OECD Countries" (PDF). Civitas. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Recorded Crime - Victims, 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2023-10-06.

- 1 2 "Crime in the US 2018 Table 16". Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- 1 2 Morgan, Rachel; Oudekerk, Barbara. "2018 National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) Criminal Victimization, 2018" (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ↑ "Crime in the US 2018 Table 16". Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ↑ Morgan, Rachel; Oudekerk, Barbara. "2018 National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) Criminal Victimization, 2018" (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ↑ "Personal Safety, Australia, 2012". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 11 December 2013. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ↑ "Table 1". FBI. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ↑ "Crime in Canada, Canada Statistics". Archived from the original on August 28, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ↑ "Table 12". FBI. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ↑ Jenkins, P. (1988). "Myth and murder: the serial killer panic of 1983–1985", Criminal Justice Research Bulletin. 3(11) 1–7.

- ↑ "FBI – Expanded Homicide Data – 2014 Archived May 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

- 1 2 Keith Krause; Eric G. Berman, eds. (August 2007). "Small Arms Survey 2007 – Chapter 2. Completing the Count: Civilian Firearms". Geneva, Switzerland: Small Arms Survey. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ↑ Vladeta Ajdacic-Gross; Martin Killias; Urs Hepp; Erika Gadola; Matthias Bopp; Christoph Lauber; Ulrich Schnyder; Felix Gutzwiller; Wulf Rössler (October 2006). "Firearm suicides and the availability of firearms: analysis of longitudinal international data". Am J Public Health. Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, US. 96 (10): 1752–55. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.075812. PMC 1586136. PMID 16946021.

- ↑ Killias, Martin (August 1993). "Gun Ownership, Suicide and Homicide: An International Perspective" (PDF). Understanding Crime Experiences of Crime and Crime Control. Acts of the International Conference, Rome, November 18–20, 1992. Vol. Publication No. 49. United Nations Publication, Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI). pp. 289–302. Sales No. E.93.III.N.2; NCJ 146360. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ↑ "CDC WISQARS Fatal Injury Reports, National and Regional, 1999–2014". Atlanta, GA: US Centers for Disease Control. Archived from the original on October 4, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ↑ Fox, Kara; Shveda, Krystina; Croker, Natalie; Chacon, Marco (November 26, 2021). "How US gun culture stacks up with the world". CNN. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021.

CNN's attribution: Developed countries are defined based on the UN classification, which includes 36 countries. Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global Burden of Disease 2019), Small Arms Survey (Civilian Firearm Holdings 2017)

- ↑ Max Ehrenfreund (December 3, 2015). "We've had a massive decline in gun violence in the United States. Here's why". Washington Post. Washington, DC. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Firearms Commerce in the United States: Annual Statistical Update 2015". Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. March 15, 2016. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ↑ "UNICEF Annual Report 2017". UNICEF. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ↑ BBC – America's child death shame Archived November 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, October 17, 2011

- ↑ James, Nathan (2015-10-29). "Is Violent Crime in the United States Increasing?". Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-18 – via Digital Library.

- 1 2 "Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities 2016: Statistics and Interventions". Child Welfare Information Gateway. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ↑ Patterns of intergenerational child protective services involvement

- ↑ "2017 Hotline Statistics". Polaris Project. 2018-03-12. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- 1 2 3 "Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children". Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ↑ "More Than 2,300 Suspected Online Child Sex Offenders Arrested During Operation 'Broken Heart'". US Department of Justice. 2018-06-12. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- 1 2 3 "Crime in the United States by Community Type". FBI. 2011. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Regional Crime Rate Figure". FBI. 2019. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Crime in the United States by State". FBI. 2019.

- ↑ "Louisiana tops murder rate again, new FBI data shows". Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- 1 2 3 "Caution Against Ranking". FBI. 2011. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Crime in the United States by Metropolitan Statistical Area". FBI. 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ↑ Ross, J.I. (2013). Encyclopedia of Street Crime in America. SAGE Publications. p. 435. ISBN 978-1-5063-2028-1. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 Fields, Gary; Emshwiller, John R. (July 23, 2011). "Many Failed Efforts to Count Nation's Federal Criminal Laws". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Baker, John S. (June 16, 2008), Revisiting the Explosive Growth of Federal Crimes, The Heritage Foundation, archived from the original on June 4, 2013, retrieved June 15, 2013

- ↑ Fields, Gary; Emshwiller, John R. (July 23, 2011). "As Criminal Laws Proliferate, More Are Ensnared". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ↑ Neil, Martha (June 14, 2013). "ABA leader calls for streamlining of 'overwhelming' and 'often ineffective' federal criminal law". ABA Journal. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ↑ Savage, David G. (January 1, 1999). "Rehnquist Urges Shorter List of Federal Crimes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ↑ Weiss, Debra Cassens (July 25, 2011). "Federal Laws Multiply: Jail Time for Misappropriating Smokey Bear Image?". ABA Journal. Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ↑ 26 million recorded crimes on average a year in the US. Ruger, Todd (June 14, 2013), "Way Too Many Criminal Laws, Lawyers Tell Congress", Blog of Legal Times, ALM, archived from the original on June 18, 2013, retrieved June 15, 2013

Further reading

External links

- 15 Most Wanted by U.S. Marshals Archived 2021-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- The FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives

- Surviving Crime Archived 2021-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Latest Crime Stats Released (FBI)

- DEA Fugitives, Major International Fugitives

- Metropolitan Police Department: Most Wanted

- New York State's 100 Most Wanted Fugitives

- All Most Wanted – official website of the Los Angeles Police Department

- Nationmaster – Worldwide statistics

- Open data on US violent crime

- Top 10 cities in USA with lowest recorded crime rates

- U. S. Crime and Imprisonment Statistics Total and by State from 1960 – Current

.svg.png.webp)