In concurrent programming, concurrent accesses to shared resources can lead to unexpected or erroneous behavior, so parts of the program where the shared resource is accessed need to be protected in ways that avoid the concurrent access. One way to do so is known as a critical section or critical region. This protected section cannot be entered by more than one process or thread at a time; others are suspended until the first leaves the critical section. Typically, the critical section accesses a shared resource, such as a data structure, a peripheral device, or a network connection, that would not operate correctly in the context of multiple concurrent accesses.[1]

Need for critical sections

Different codes or processes may consist of the same variable or other resources that need to be read or written but whose results depend on the order in which the actions occur. For example, if a variable x is to be read by process A, and process B has to write to the same variable x at the same time, process A might get either the old or new value of x.

Process A:

// Process A

.

.

b = x + 5; // instruction executes at time = Tx

.

Process B:

// Process B

.

.

x = 3 + z; // instruction executes at time = Tx

.

In cases where a locking mechanism with finer granularity is not needed, a critical section is important. In the above case, if A needs to read the updated value of x, executing process A, and process B at the same time may not give required results. To prevent this, variable x is protected by a critical section. First, B gets the access to the section. Once B finishes writing the value, A gets the access to the critical section, and variable x can be read.

By carefully controlling which variables are modified inside and outside the critical section, concurrent access to the shared variable are prevented. A critical section is typically used when a multi-threaded program must update multiple related variables without a separate thread making conflicting changes to that data. In a related situation, a critical section may be used to ensure that a shared resource, for example, a printer, can only be accessed by one process at a time.

Implementation of critical sections

The implementation of critical sections vary among different operating systems.

A critical section will usually terminate in finite time,[2] and a thread, task, or process will have to wait for a fixed time to enter it (bounded waiting). To ensure exclusive use of critical sections some synchronization mechanism is required at the entry and exit of the program.

Critical section is a piece of a program that requires mutual exclusion of access.

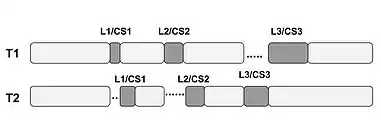

As shown in the figure,[3] in the case of mutual exclusion (mutex), one thread blocks a critical section by using locking techniques when it needs to access the shared resource, and other threads have to wait to get their turn to enter into the section. This prevents conflicts when two or more threads share the same memory space and want to access a common resource.[2]

The simplest method to prevent any change of processor control inside the critical section is implementing a semaphore. In uniprocessor systems, this can be done by disabling interrupts on entry into the critical section, avoiding system calls that can cause a context switch while inside the section, and restoring interrupts to their previous state on exit. Any thread of execution entering any critical section anywhere in the system will, with this implementation, prevent any other thread, including an interrupt, from being granted processing time on the CPU—and therefore from entering any other critical section or, indeed, any code whatsoever—until the original thread leaves its critical section.

This brute-force approach can be improved upon by using semaphores. To enter a critical section, a thread must obtain a semaphore, which it releases on leaving the section. Other threads are prevented from entering the critical section at the same time as the original thread, but are free to gain control of the CPU and execute other code, including other critical sections that are protected by different semaphores. Semaphore locking also has a time limit to prevent a deadlock condition in which a lock is acquired by a single process for an infinite time, stalling the other processes that need to use the shared resource protected by the critical section.

Uses of critical sections

Kernel-level critical sections

Typically, critical sections prevent thread and process migration between processors and the preemption of processes and threads by interrupts and other processes and threads.

Critical sections often allow nesting. Nesting allows multiple critical sections to be entered and exited at little cost.

If the scheduler interrupts the current process or thread in a critical section, the scheduler will either allow the currently executing process or thread to run to completion of the critical section, or it will schedule the process or thread for another complete quantum. The scheduler will not migrate the process or thread to another processor, and it will not schedule another process or thread to run while the current process or thread is in a critical section.

Similarly, if an interrupt occurs in a critical section, the interrupt information is recorded for future processing, and execution is returned to the process or thread in the critical section.[4] Once the critical section is exited, and in some cases the scheduled quantum completed, the pending interrupt will be executed. The concept of scheduling quantum applies to "round-robin" and similar scheduling policies.

Since critical sections may execute only on the processor on which they are entered, synchronization is only required within the executing processor. This allows critical sections to be entered and exited at almost zero cost. No inter-processor synchronization is required. Only instruction stream synchronization[5] is needed. Most processors provide the required amount of synchronization by the simple act of interrupting the current execution state. This allows critical sections in most cases to be nothing more than a per processor count of critical sections entered.

Performance enhancements include executing pending interrupts at the exit of all critical sections and allowing the scheduler to run at the exit of all critical sections. Furthermore, pending interrupts may be transferred to other processors for execution.

Critical sections should not be used as a long-lasting locking primitive. Critical sections should be kept short enough so that it can be entered, executed, and exited without any interrupts occurring from the hardware and the scheduler.

Kernel-level critical sections are the base of the software lockout issue.

Critical sections in data structures

In parallel programming, the code is divided into threads. The read-write conflicting variables are split between threads and each thread has a copy of them. Data structures like linked lists, trees, hash tables etc. have data variables that are linked and cannot be split between threads and hence implementing parallelism is very difficult.[6] To improve the efficiency of implementing data structures multiple operations like insertion, deletion, search need to be executed in parallel. While performing these operations, there may be scenarios where the same element is being searched by one thread and is being deleted by another. In such cases, the output may be erroneous. The thread searching the element may have a hit, whereas the other thread may delete it just after that time. These scenarios will cause issues in the program running by providing false data. To prevent this, one method is that the entire data-structure can be kept under critical section so that only one operation is handled at a time. Another method is locking the node in use under critical section, so that other operations do not use the same node. Using critical section, thus, ensures that the code provides expected outputs.[6]

Critical sections in relation to peripherals

Critical sections also occur in code which manipulates external peripherals, such as I/O devices. The registers of a peripheral must be programmed with certain values in a certain sequence; if two or more processes control a device simultaneously, incorrect behavior will ensue: neither process will have the device in the state which it requires.

When a complex unit of information must be produced on an output device by issuing multiple output operations, exclusive access is required so that another process doesn't corrupt the datum by interleaving its own bits of output.

In the input direction, exclusive access is required when reading a complex datum via multiple separate input operations, to prevent another process from consuming some of the pieces, causing corruption.

Storage devices provide a form of memory; the concept of critical sections is equally relevant in the same manner as it is to shared data structures in main memory. A process which performs multiple access or update operations on a file is executing a critical section that must be guarded with an appropriate file locking mechanism.

See also

References

- ↑ Raynal, Michel (2012). Concurrent Programming: Algorithms, Principles, and Foundations. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 9. ISBN 978-3642320279.

- 1 2 Jones, M. Tim (2008). GNU/Linux Application Programming (2nd ed.). [Hingham, Mass.] Charles River Media. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-58450-568-6.

- ↑ Chen, Stenstrom, Guancheng, Per (Nov 10–16, 2012). "Critical lock analysis: Diagnosing critical section bottlenecks in multithreaded applications". 2012 International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1109/sc.2012.40. ISBN 978-1-4673-0805-2. S2CID 12519578.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "RESEARCH PAPER ON SOFTWARE SOLUTION OF CRITICAL SECTION PROBLEM". International Journal of Advance Technology & Engineering Research (IJATER). 1. November 2011.

- ↑ Dubois, Scheurich, Michel, Christoph (1988). "Synchronization, Coherence, and Event Ordering in Multiprocessors". Survey and Tutorial Series. 21 (2): 9–21. doi:10.1109/2.15. S2CID 1749330.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Solihin, Yan (17 November 2015). Fundamentals of Parallel Multicore Architecture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781482211184.