The first African drums were heard in Cuba, since the 16th century, only during the celebration of certain feasts, such as the Día de Reyes (Three Kings Day) and Carnestolendas or Carnival, because their use was restricted to some mutual aid societies, called "Cabildos de nación", where the slaves and their descendants were allowed to gather and practice their cultural and religious traditions.

The music and dance of the Cuban Carnival was always very popular in Cuba, and has exerted an important influence in other genres of the Cuban music, such as the "Conga de Salón" and the "Mozambique" rhythm.[1] the Cuban Conga has transcended the national frontiers to become one of the most famous and cherished genres of the Cuban music outside the country, like the well known Congas de Salón from the late 1930s and early 1940s Bim Bam Bum, from Rafael Hernández and Uno, dos y tres, from Rafael Ortiz, which at a later time was known in English as: One, two, three, Kick![2] Most recently, in 1985, the famous "Conga" from the Cuban-American group Miami Sound Machine, triggered a true frenzy in the US and all around the world. Its success is only comparable to the popularity of the 1930s Conga de Salón or the Conga lines of Desi Arnaz during the 1950s.

From the 16th to the 18th century

The cultural and physical mixing of blacks and whites in Cuba began with the arrival to the Island of the first slave African women around 1550[3] but their cultures remained relatively independent one from the other for hundreds of years, because the slaves didn't have access to their Masters cultural traditions, and the Spanish people perceived the African culture as barbaric and primitive. The following description of a black slave's feast, included in a story from the "costumbrista" writer Francisco Baralt, evidence the negative image that the Spanish had toward the cultural manifestations of the Africans. According to Baralt: "those (African) dances have such a weird aspect, because of the place, the time and the individuals that perform them, that even those who observe them every day receive an impression difficult to express: we don’t know if it is curiosity or disgust, if it repels or attract its primitive and savage character, that seem to put between this feasts and those of the white men the same distance that exists between the deluge and our times."[4]

The music from the African people that arrived to Cuba from Spain, or directly from Africa, was only allowed since the beginning of Colonial times, within certain mutual aid societies and religious fraternities which foundation dates from the 16th century. According to David H. Brown, those societies, called Cabildos, "provided aid in case of disease or death, celebrated masses for the souls of the death, collected funds for the liberation from slavery of its members, regularly organized dances and recreational activities during Sundays and Holidays, and sponsored masses, processions and Carnival dances (now called "comparsas") around the annual cycle of Catholic festivals"[5]

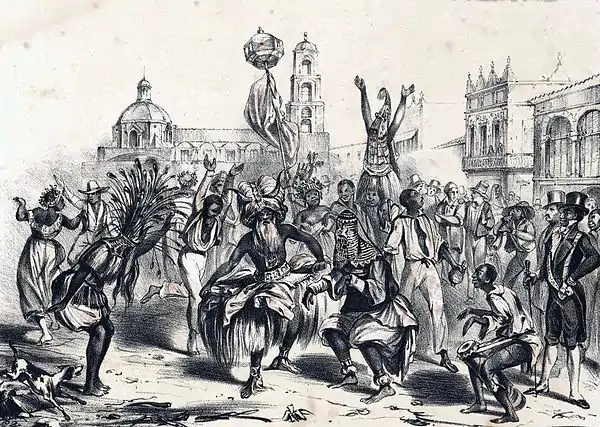

The Cabildos organized big street processions during Sundays, the celebration of Saints and some important Holidays, where their leaders and companions dressed with clothes appropriate for the royalty and high rank military, while those who participated in the processions and dances wear "feathered head pieces and African masks with horns and vegetal ornaments." The Three Kings Day, celebrated on January 6, during the Epiphany, was the most important of those festivities.[6]

Another important feast where the Cabildos participated was celebrated during the three days before "Ash Wednesday", which at a later time became the Carnestolendas or Carnival.[7] In 1697, the Italian Gemeli Careri mentioned those celebrations: "… on Sunday, February 9th, the black and mulatoes, with picturesque apparels, formed a gathering to have fun at the Carnival." According to Virtudes Feliú: "… This is the most ancient information about the traditional Havanese "comparsas", and it makes clear that, indeed, the blacks and mulatoes enjoyed themselves at the Carnestolendas that Hispanics and their descendants celebrated, wearing unusual clothes related to those feasts in a gathering that Careri called a "congregation", most probable because the term "comparsa" was not yet in use."[8]

We can assume that the musical instruments utilized in the old Cabildos were the African membranophones that were not utilized in the ritual celebrations, such as the bembé and yuka drums. In reference to the difference between the ritual African drums, that should only be played in religious ceremonies, and the secular drums, that may actually be played in public, Argelier León remarks: "Differently from the ritual drums batá and iyesá, which were tuned with a tensor system in N…, the bembé drums could be tuned by applying heat, because they didn’t possess the ritual character of the consecrated drums."

León also says that "…The bembé drums are varied, from those of a big size – more than a meter tall and of a cylindrical shape – to small drums made from containers. In certains areas of Cuba, the bembé drums are made from palm tree trunks, with just one nailed drumhead, and little more than half a meter tall…"[9]

The yuka ensemble was composed by three drums made from raw wooden trunks (called in size order: caja, mula and cachimbo) with hide drum-heads nailed to the body. They also utilized a hollow bambu piece beaten with two bamboo sticks called "guagua’’ or "catá"; and also beating over the drum side.[10]

In reference to the drums utilized by the Africans in their feasts, the "costumbrista" author Francisco Baralt wrote around 1846: "The only instrument they use in these feasts is a type of drum made from one wooden piece of about two to four feet long. With an irregular ..and a more or less conical or cylindrical shape. It was hollowed up to half of its size, and usually covered over its larger side with a raw goat hide."[11]

These descriptions also coincide with the visual representations of the Carnivals, during the 19th century, by artists such as Víctor Patricio de Landaluze and Federico Miahle; where frequently appear some cylindrical drums with a nailed hide on the top, performed between the legs of the standing drummer, in a very similar way as the yuka drums are played even today. In numerous prints of Landaluze and Miahle about the Carnival festivities, we can observe some musical instruments, like drums and horns, that were utilized at that time. In a famous Miahle print from 1855, called Three Kings Days, we can see a drummer to the left side, playing a cylindric drum between his legs, and another man at the back, with a hat, blowing a curved horn.

The 19th century

According with David H. Brown: "After 1792, when the Cabildos were relegated to the "extramuros" zone of the city, the Carnival processions came out of their locations and went through the entrances toward the fortified "intramuros" area. They marched through the residential and commercial streets of Mercaderes, Obispo and O’Reilly until they reached the central Plaza de Armas, the site of the Captain General of the Island Palace. Inside the Palace patio, as in other stops along the way, the procession's members represented dances, asked for and received gifts (aguinaldos), and after that, they returned to their homes."[12]

In the following story from 1866, the author mentions the characteristic sounds as well as the instruments that were performed by those participants in the procession of a Three Kings Day "comparsa" in Havana:

"Innumerable groups of black Africans "comparsas" went along through every street of the Capital city. The hurly-burly is immense and its aspect horrifying... The great noise created by all the drums, horns and whistles deafen the passers-by everywhere; in a corner a Yoruba king surrounded by his court of blacks, here a Gangá, another one there from a Carabalí nation... all of them, kings for a day, singing in a monotonous and unpleasant drone in their African languages."[13]

The 20th century

At the beginning of the Independence war, in 1895, the colonial authorities banned all the Carnival activities indefinitely, and this prohibition stayed in effect until the conclusion of the hostilities, at the beginning of the 20th century.

The Mayor of Havana, Carlos de La Torre, reinstate the Carnival festivities officially in 1902. The massive participation of a population of African origin in the Independence war resulted in a greater integration of the Afro-Cubans in social activities, and facilitated a more important participation of this segment of the population in the Carnival during the first years of the Republic. For the first time blacks were allowed to play their music and dances along with the "comparsas" of white people, such as El Alacrán, the Model T cars covered by flower arrangements and the "carrozas" (floats).[14]

Since 1902, the municipal authorities began again to strictly regulate the organization of the Carnival processions, showing a preference for the ornamented cars, the floats, the military bands, and the presentation of the King and the Queen, in detriment of the manifestation of Afro-Cuban origin, such as the "comparsa" and the Conga, and around 1916, the suppression of the "comparsa" groups in Havana was almost total.[15] Because during the period from the 1900s and 1910s, the Carnival activities have attracted thousands of foreign visitors to the Capital each spring, finally in 1937, the authorities of the city decided to reauthorize the "comparsas" in the Carnival "paseos" (strolls).[16]

In 1937, the "comparsas" began to permanently participate in the Havanese Carnivals, parading through the Paseo del Prado with distinctive choreographies, dances and songs. Those groups included: El Alacrán, from the Cerro neighborhood, Los Marqueses from Atarés, Las Boyeras from Los Sitios, Los Dandys from Belén, La Sultana from Colón, Las Jardineras from Jesús María, Los Componedoras de Batea from Cayo Hueso, El Príncipe del Raj from Marte, las Mexicanas from Dragones, Los Moros Azules from Guanabacoa, El Barracón from Pueblo Nuevo and Los Guaracheros from Regla.

Celebrados en el mes de Julio, Los Carnavales de Santiago de Cuba y otros pueblos orientales poseían sus propias características. En vez de encontrarse reducidas a ciertas calles y plazas como en la capital, las comparsas santiagueras se extendían a toda la ciudad y la población participaba más activamente en ellas. El estilo y el carácter de la música y la danza eran también differentes.[17]

Soon after 1959, the Revolutionary authorities changed the celebration of the Carnivals from February and March to July 26. At the beginning, this change was made in order not to interrupt the sugar cane harvest in 1979, but it was kept in place at a later time with the purpose of celebrating the "triumph of socialism." Between 1990 and 1995 isolated presentations were offered, which were associated to political events. Those included some groups that went to the streets in November 1993, in order to celebrate the anniversary of the CDRs (Revolution Defense Committees). Finally, in an attempt to attract a larger number of tourists, the government authorized again a modest Carnival celebration, preceding the celebration of Lent (Cuaresma), instead of in July, when it was previously accustomed.[18]

Music of the Cuban Carnival

The Cuban Carnival music ensembles used to be varied, but it is also possible to determine certain patterns in reference to the instrumental groups utilized in Havana and Santiago de Cuba, which differ significantly.

This is how Argeliers León describes the basic instrumental of the Havanese comparsa: "…In other zones of the population still remained other instrumental groups such as those of the comparsas, comprised of a Conga, a tumbadora and a quinto, a snare drum (without the snares), a double cow-bell or "jimagua", a bass drum or two frying pans attached to a wooden box or a board. This equipment may be expanded with two tumbadoras and one or more trumpets.[19]

The drum called Conga or tumbadora, of an evident Bantu origin, is, according to Fernando Ortiz: "… a drum from African origin, made of wooden slabs and iron rings, from approximately a meter long, barrel shape, and opened on one end with only one hide drumhead fixed by nails to the body of the drum…" It was tuned using heat in the past, but currently is tuned with metallic tuning pegs.[20]

The tumbadora's diameter are as follows, from treble to bass: requinto (9 to 10 inches), quinto (10 t 11 inches), Conga (macho or tres-dos) (11 to 12 inches), tumbadora (or hembra) (12 to 13 inches), retumbadora (or mambisa) (14 inches).

In the comparsas and Congas of Santiago de Cuba various bimembranophone drums, beaten with drumsticks, are utilized: one requinto, three Congas (without any relationship with the Havanese Conga), which are subdivided in two redoblantes or galletas, and one pilón. They also utilize various membranophone drums (with a conical shape and only one drumhead, played with the palms of the hands) called bocúes. The drums are complemented by three percuted metallic idiophones (made from discarded wheel rims), which are selected considering its sonority.[21]

The wind instruments are represented by the piercing sound of the corneta china, a double-reed Chinese instrument that was inserted in the Santiago de Cuba Congas in 1915.,[22] and that always performs the initial call to start the Conga (arrollar), which is how the dancing style of the Conga is called, characterized by a peculiar form of rhythmic march, dragging the feet and moving the hips and shoulders along with the music rhythm.

The musical style of the Havanese Conga is quite different from the Conga Santiaguera, and maybe the element that mostly differentiate both styles is a peculiar rhythmic accent within the 4/4 meter, which is executed by the Havanese Bass drum or the Conga (drum) from Santiago, respectively.

In the Havanese style, this accent falls on a syncopated note on the third beat of the measure, configurating a very well known rhythmic pattern (one, two, three, cick). In the Conga from Santiago, the stressed beats of the measure are more emphasized, thus inducing a powerful impulse feeling, which incites to move the feet along with the rhythmic pulse. In this case, the drum accent is played between the fourth beat of the previous measure and the first of the following measure.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ Rodríguez Ruidíaz, Armando :Los sonidos de la música cubana. Evolución de los formatos instrumentales en Cuba, p. 56. https://www.academia.edu/18302881/Los_sonidos_de_la_m%C3%BAsica_cubana._Evoluci%C3%B3n_de_los_formatos_instrumentales_en_Cuba

- ↑ Torres, George (2013-03-27). Encyclopedia of Latin American Popular Music. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-08794-3.

- ↑ Fernández Escobio, Fernando: Raíces de la nacionalidad cubana, Miami, Florida, 1992, p. 227.

- ↑ Baralt, Francisco: Escenas campestres. Baile de los negros. Costumbristas cubanos del siglo XIX, Selección, prólogo, cronología y bibliografía Salvador Bueno, Consultado: Agosto 25, 2010, http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/costumbristas-cubanos-del-siglo-xix--2/html/fef805c0-82b1-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_7.htm

- ↑ Brown, David H.: Santería enthroned, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2003, p. 34.

- ↑ Brown, David H.: Santería enthroned, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2003, p. 34.

- ↑ Feliú, Virtudes: La Fiesta. Fiestas populares tradicionales de Cuba. Instituto Andino de Artes Populares, p. 83.

- ↑ Feliú, Virtudes: La Fiesta. Fiestas populares tradicionales de Cuba. Instituto Andino de Artes Populares, p. 86.

- ↑ León, Argeliers: Del canto y del tiempo. Editorial Pueblo y Educación. La Habana, Cuba, 1981, p. 46.

- ↑ León, ArgeliDel canto y del tiempo. Editorial Pueblo y Educación. La Habana, Cuba, 1981, p. 67.

- ↑ Baralt, Francisco: Escenas Campestres, Baile de los negros. http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/costumbristas-cubanos-del-siglo-xix--2/html/fef805c0-82b1-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_7.htm. Consultado 12-23-15.

- ↑ Brown, David H.: Santería enthroned, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2003, p. 35.

- ↑ Moore, Robin D.: Nationalizing blackness. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. Pa., 1997, p. 65.

- ↑ Moore, Robin D.: Nationalizing blackness. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. Pa., 1997, p. 68.

- ↑ Moore, Robin D.: Nationalizing blackness. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. Pa., 1997, p. 69.

- ↑ Moore, Robin D.: Nationalizing blackness. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. Pa., 1997, p. 83.

- ↑ Orovio, Helio: Cuban music from A to Z. Tumi Music Ltd. Bath, U.K., 2004, p. 45.

- ↑ Moore, Robin D.: Nationalizing blackness. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. Pa., 1997, p. 85.

- ↑ León, Argeliers: Del canto y del tiempo. Editorial Pueblo y Educación. La Habana, Cuba, 1981, p. 29.

- ↑ Orovio, Helio: Cuban music from A to Z. Tumi Music Ltd. Bath, U.K., 2004, p. 57.

- ↑ Rodríguez Ruidíaz, Armando: El carnaval cubano y su música, p. 11. https://www.academia.edu/19810545/El_Carnaval_Cubano_y_su_m%C3%BAsica

- ↑ Pérez Fernández, Rolando:The Chinese community and the corneta china: Two divergent paths in Cuba, Yearbook 2014, p. 79.

- ↑ Rodríguez Ruidíaz, Armando: El carnaval cubano y su música, p. 12-13. https://www.academia.edu/19810545/El_Carnaval_Cubano_y_su_m%C3%BAsica