In organic chemistry, the cycloalkanes (also called naphthenes, but distinct from naphthalene) are the monocyclic saturated hydrocarbons.[1] In other words, a cycloalkane consists only of hydrogen and carbon atoms arranged in a structure containing a single ring (possibly with side chains), and all of the carbon-carbon bonds are single. The larger cycloalkanes, with more than 20 carbon atoms are typically called cycloparaffins. All cycloalkanes are isomers of alkenes.[2]

The cycloalkanes without side chains are classified as small (cyclopropane and cyclobutane), common (cyclopentane, cyclohexane, and cycloheptane), medium (cyclooctane through cyclotridecane), and large (all the rest).

Besides this standard definition by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), in some authors' usage the term cycloalkane includes also those saturated hydrocarbons that are polycyclic.[2] In any case, the general form of the chemical formula for cycloalkanes is CnH2(n+1−r), where n is the number of carbon atoms and r is the number of rings. The simpler form for cycloalkanes with only one ring is CnH2n.

Nomenclature

Unsubstituted cycloalkanes that contain a single ring in their molecular structure are typically named by adding the prefix "cyclo" to the name of the corresponding linear alkane with the same number of carbon atoms in its chain as the cycloalkane has in its ring. For example, the name of cyclopropane (C3H6) containing a three-membered ring is derived from propane (C3H8) - an alkane having three carbon atoms in the main chain.

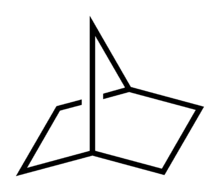

The naming of polycyclic alkanes such as bicyclic alkanes and spiro alkanes is more complex, with the base name indicating the number of carbons in the ring system, a prefix indicating the number of rings ( "bicyclo-" or "spiro-"), and a numeric prefix before that indicating the number of carbons in each part of each ring, exclusive of junctions. For instance, a bicyclooctane that consists of a six-membered ring and a four-membered ring, which share two adjacent carbon atoms that form a shared edge, is [4.2.0]-bicyclooctane. That part of the six-membered ring, exclusive of the shared edge has 4 carbons. That part of the four-membered ring, exclusive of the shared edge, has 2 carbons. The edge itself, exclusive of the two vertices that define it, has 0 carbons.

There is more than one convention (method or nomenclature) for the naming of compounds, which can be confusing for those who are just learning, and inconvenient for those who are well-rehearsed in the older ways. For beginners, it is best to learn IUPAC nomenclature from a source that is up to date,[3] because this system is constantly being revised. In the above example [4.2.0]-bicyclooctane would be written bicyclo[4.2.0]octane to fit the conventions for IUPAC naming. It then has room for an additional numerical prefix if there is the need to include details of other attachments to the molecule such as chlorine or a methyl group. Another convention for the naming of compounds is the common name, which is a shorter name and it gives less information about the compound. An example of a common name is terpineol, the name of which can tell us only that it is an alcohol (because the suffix "-ol" is in the name) and it should then have a hydroxyl group (–OH) attached to it.

The IUPAC naming system for organic compounds can be demonstrated using the example provided in the adjacent image. The base name of the compound, indicating the total number of carbons in both rings (including the shared edge), is listed first. For instance, "heptane" denotes "hepta-", which refers to the seven carbons, and "-ane", indicating single bonding between carbons. Next, the numerical prefix is added in front of the base name, representing the number of carbons in each ring (excluding the shared carbons) and the number of carbons present in the bridge between the rings. In this example, there are two rings with two carbons each and a single bridge with one carbon, excluding the carbons shared by both the rings. The prefix consists of three numbers that are arranged in descending order, separated by dots: [2.2.1]. Before the numerical prefix is another prefix indicating the number of rings (e.g., "bicyclo-"). Thus, the name is bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane.

The group of cycloalkanes are also known as naphthenes.

Properties

Table of cycloalkanes

| Alkane | Formula | Boiling point [°C] | Melting point [°C] | Liquid density [g·cm−3] (at 20 °C) |

| Cyclopropane | C3H6 | −33 | −128 | |

| Cyclobutane | C4H8 | 12.5 | −91 | 0.720 |

| Cyclopentane | C5H10 | 49.2 | −93.9 | 0.751 |

| Cyclohexane | C6H12 | 80.7 | 6.5 | 0.778 |

| Cycloheptane | C7H14 | 118.4 | −12 | 0.811 |

| Cyclooctane | C8H16 | 149 | 14.6 | 0.834 |

| Cyclononane | C9H18 | 169 | 10-11 | 0.8534 |

| Cyclodecane | C10H20 | 201 | 9-10 | 0.871 |

Cycloalkanes are similar to alkanes in their general physical properties, but they have higher boiling points, melting points, and densities than alkanes. This is due to stronger London forces because the ring shape allows for a larger area of contact. Containing only C–C and C–H bonds, unreactivity of cycloalkanes with little or no ring strain (see below) are comparable to non-cyclic alkanes.

Conformations and ring strain

In cycloalkanes, the carbon atoms are sp3 hybridized, which would imply an ideal tetrahedral bond angle of 109° 28′ whenever possible. Owing to evident geometrical reasons, rings with 3, 4, and (to a small extent) also 5 atoms can only afford narrower angles; the consequent deviation from the ideal tetrahedral bond angles causes an increase in potential energy and an overall destabilizing effect. Eclipsing of hydrogen atoms is an important destabilizing effect, as well. The strain energy of a cycloalkane is the increase in energy caused by the compound's geometry, and is calculated by comparing the experimental standard enthalpy change of combustion of the cycloalkane with the value calculated using average bond energies. Molecular mechanics calculations are well suited to identify the many conformations occurring particularly in medium rings.[4]: 16–23

Ring strain is highest for cyclopropane, in which the carbon atoms form a triangle and therefore have 60 °C–C–C bond angles. There are also three pairs of eclipsed hydrogens. The ring strain is calculated to be around 120 kJ mol−1.

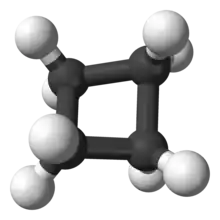

Cyclobutane has the carbon atoms in a puckered square with approximately 90° bond angles; "puckering" reduces the eclipsing interactions between hydrogen atoms. Its ring strain is therefore slightly less, at around 110 kJ mol−1.

For a theoretical planar cyclopentane the C–C–C bond angles would be 108°, very close to the measure of the tetrahedral angle. Actual cyclopentane molecules are puckered, but this changes only the bond angles slightly so that angle strain is relatively small. The eclipsing interactions are also reduced, leaving a ring strain of about 25 kJ mol−1.[5]

In cyclohexane the ring strain and eclipsing interactions are negligible because the puckering of the ring allows ideal tetrahedral bond angles to be achieved. In the most stable chair form of cyclohexane, axial hydrogens on adjacent carbon atoms are pointed in opposite directions, virtually eliminating eclipsing strain. In medium-sized rings (7 to 13 carbon atoms) conformations in which the angle strain is minimised create transannular strain or Pitzer strain. At these ring sizes, one or more of these sources of strain must be present, resulting in an increase in strain energy, which peaks at 9 carbons (around 50 kJ mol−1). After that, strain energy slowly decreases until 12 carbon atoms, where it drops significantly; at 14, another significant drop occurs and the strain is on a level comparable with 10 kJ mol−1. At larger ring sizes there is little or no strain since there are many accessible conformations corresponding to a diamond lattice.[4]

Ring strain can be considerably higher in bicyclic systems. For example, bicyclobutane, C4H6, is noted for being one of the most strained compounds that is isolatable on a large scale; its strain energy is estimated at 267 kJ mol−1.[6][7]

Reactions

The simple and the bigger cycloalkanes are very stable, like alkanes, and their reactions, for example, radical chain reactions, are like alkanes.

The small cycloalkanes – in particular, cyclopropane – have a lower stability due to Baeyer strain and ring strain. They react similarly to alkenes, though they do not react in electrophilic addition, but in nucleophilic aliphatic substitution. These reactions are ring-opening reactions or ring-cleavage reactions of alkyl cycloalkanes. Cycloalkanes can be formed in a Diels–Alder reaction followed by a catalytic hydrogenation. Medium rings exhibit larger rates in, for example, nucleophilic substitution reactions, but smaller ones in ketone reduction. This is due to conversion from sp3- to sp2-state, or vice versa, and the preference for sp2 states in medium rings, where some of the unfavourable torsional strain in saturated rings is relieved. Molecular mechanics calculations of strain energy differences between sp3 and sp2 states show linear correlations with rates of many redox or substitution reactions.[8]

Preparation of Cycloalkane

The preparation of cycloalkanes involves several synthetic routes that can be broadly classified into two main categories: ring-closure reactions and methods involving cycloaddition reactions.

1. Ring-Closure Reactions

Hydrogenation of Alkenes

This method involves the use of a metal catalyst, typically palladium (Pd) or platinum (Pt), and hydrogen gas (H2) to saturate carbon-carbon double bonds in alkenes, forming cycloalkanes. For instance, the hydrogenation of cyclohexene results in the formation of cyclohexane.

Cyclization of Diols or Dicarboxylic Acids

Diols or dicarboxylic acids can undergo intramolecular reactions to form cyclic compounds, including cycloalkanes. This can occur through processes like esterification or dehydration of the diol or dicarboxylic acid to form the cyclic structure.

Dehydrogenation of Cycloalkanes

Certain cycloalkanes can be prepared by the dehydrogenation of other cyclic compounds. For instance, cyclohexane can undergo dehydrogenation to form benzene in the presence of a suitable catalyst and high temperatures.

2. Cycloaddition Reactions

Diels-Alder Reaction

The Diels-Alder reaction involves the concerted addition of a conjugated diene and a dienophile, resulting in the formation of a cyclohexene ring. This reaction is widely used in the synthesis of cycloalkanes and can be controlled to produce various substituted cyclohexenes.

[2+2] Cycloaddition

[2+2] Cycloaddition reactions involve the combination of two unsaturated molecules, leading to the formation of a cyclic product with the loss of two sigma bonds. For instance, the reaction between two alkynes can result in the formation of a cyclobutane ring.

Additional Methods

Reformatsky Reaction

This involves the reaction of a carbonyl compound with zinc and an organic halide, followed by treatment with water or a weak acid. The Reformatsky reaction can be used for the preparation of cycloalkanones, which can subsequently undergo ring-closure reactions to form cycloalkanes.

Grignard Reaction

While not a direct method for cycloalkane synthesis, Grignard reagents can be utilized to introduce alkyl or aryl groups onto carbonyl compounds. These compounds can then undergo further reactions leading to the formation of cyclic structures, including cycloalkanes.

See also

References

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2014) "Cycloalkane". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01497

- 1 2 "Alkanes & Cycloalkanes". www2.chemistry.msu.edu. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ↑ "Blue Book". iupac.qmul.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- 1 2 Dragojlovic, Veljko (2015). "Conformational analysis of cycloalkanes" (PDF). Chemtexts. 1 (3). doi:10.1007/s40828-015-0014-0. S2CID 94348487.

- ↑ McMurry, John (2000). Organic chemistry (5th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. p. 126. ISBN 0534373674.

- ↑ Wiberg, K. B. (1968). "Small Ring Bicyclo[n.m.0]alkanes". In Hart, H.; Karabatsos, G. J. (eds.). Advances in Alicyclic Chemistry. Vol. 2. Academic Press. pp. 185–254. ISBN 9781483224213.

- ↑ Wiberg, K. B.; Lampman, G. M.; Ciula, R. P.; Connor, D. S.; Schertler, P.; Lavanish, J. (1965). "Bicyclo[1.1.0]butane". Tetrahedron. 21 (10): 2749–2769. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)98361-9.

- ↑ Schneider, H.-J.; Schmidt, G.; Thomas F. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1983, 105, 3556. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ja00349a031

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (1995) "Cycloalkanes". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01497

- Organic Chemistry IUPAC Nomenclature. Rule A-23. Hydrogenated Compounds from Fused Polycyclic Hydrocarbons http://www.acdlabs.com/iupac/nomenclature/79/r79_73.htm

- Organic Chemistry IUPAC Nomenclature.Rule A-31. Bridged Hydrocarbons: Bicyclic Systems. http://www.acdlabs.com/iupac/nomenclature/79/r79_163.htm

- Organic Chemistry IUPAC Nomenclature.Rules A-41, A-42: Spiro Hydrocarbons http://www.acdlabs.com/iupac/nomenclature/79/r79_196.htm

- Organic Chemistry IUPAC Nomenclature.Rules A-51, A-52, A-53, A-54:Hydrocarbon Ring Assemblies http://www.acdlabs.com/iupac/nomenclature/79/r79_158.htm

External links

- "Cycloalkanes" at the online Encyclopædia Britannica