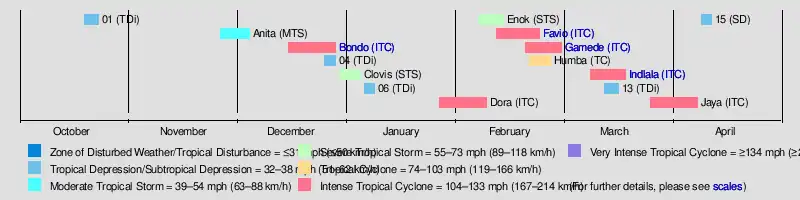

| 2006–07 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | October 19, 2006 |

| Last system dissipated | April 12, 2007 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Dora & Favio |

| • Maximum winds | 195 km/h (120 mph) (10-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 925 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total disturbances | 15 |

| Total depressions | 11 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Tropical cyclones | 7 |

| Intense tropical cyclones | 6 |

| Total fatalities | 180 total |

| Total damage | $431 million (2007 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 2006–07 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season featured the second-most intense tropical cyclones for a season in the tropical cyclone basin, only behind the 2018–19 season. The basin contains the waters of the Indian Ocean south of the equator and west of 90°E. Météo-France's meteorological office in Réunion (MFR), the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the South-West Indian Ocean, tracked 15 tropical disturbances, of which eleven attained gale-force winds. The season began in October 2006 with a short-lived tropical disturbance, followed by Anita in November, which was the first named storm of the season. Cyclone Bondo was the first of six intense tropical cyclones, which took a rare track through the southern Seychelles before making landfall on northwest Madagascar, killing 11 people. Severe Tropical Storm Clovis lasted from December 2006 to January 2007; it struck eastern Madagascar, killing four people.

In January 2007, Cyclone Dora became one of the two strongest storms of the season, with maximum sustained winds of 195 kilometres per hour (120 miles per hour); Dora only lightly affected the Mauritian island of Rodrigues. The season was most active in February, beginning with Severe Tropical Storm Enok, which formed off eastern Madagascar and later struck the island of St. Brandon. The next storm, Cyclone Favio, tied Dora as the season's strongest storm. Favio took an unusual path south of Madagascar before entering the Mozambique Channel and striking southern Mozambique, killing 10 people and causing widespread flooding. Cyclone Gamede stalled northwest of the Mascarene Islands for a few days in late February, resulting in historic rainfall totals on the French island of Réunion. Over a nine-day period, Gamede dropped 5512 mm (217 in) of rainfall at Commerson Crater, making it one of the wettest tropical cyclones on record. February concluded with Cyclone Humba, which remained over the eastern portion of the basin.

The season's deadliest storm was Cyclone Indlala, which struck northeastern Madagascar on March 15. The cyclone killed 150 people and caused over US$240 million in damage, after resulting in widespread flooding. Less than three weeks after Indlala, Cyclone Jaya struck northeastern Madagascar at a similar location, disrupting ongoing relief efforts and causing one death. The season concluded on April 12, when a subtropical cyclone in the Mozambique Channel transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.

Seasonal forecast and summary

On October 13, 2006, the Mauritius Meteorological Services (MMS) issued their seasonal outlook for the South-west Indian Ocean, anticipating a normal season with about 10 named storms. They forecast El Niño conditions for the southern hemisphere, meaning that normal to slightly above normal activity was likely. They also forecast a weak quasi-biennial oscillation, which would promote cyclone formation in the basin. Other seasonal indicators that were conducive for storm formation included above normal water temperatures, sustained convective activity, and above normal humidity. The seasonal forecast anticipated that most storms would form west of Diego Garcia, with at least one forming in the Mozambique Channel.[1]

Météo-France's meteorological office in Réunion (MFR) – the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the South-West Indian Ocean – tracked all tropical cyclones from the east coast of Africa to 90° E, and south of the equator.[2] Regional warning centers in Mauritius and Madagascar formally named the individual storms.[3] The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC), which is a joint United States Navy – United States Air Force task force that issues tropical cyclone warnings for the region, also issued advisories for storms during the season.[4]

During the season, the MFR monitored 15 tropical disturbances, including a subtropical cyclone southwest of Madagascar that ended the season in April.[5][3] There were ten systems that attained the intensity of a moderate tropical storm, which has 10–minute sustained winds of at least 65 km/h (40 mph); this is near the long-term average, but much more active than the previous season. There were 58 days in which a tropical storm was active, or five more than the average. Seven of these storms attained tropical cyclone status, which has 10–minute winds of 120 km/h (75 mph); the 30 days with a tropical cyclone present was 10 days more than average. Of these cyclones, six strengthened further to an intense tropical cyclone, which has 10 minute winds of 165 km/h (105 mph). This was the most on record at the time,[6] until it was surpassed by the 2018–19 season.[7] The rest of the southern hemisphere was less active than the Indian Ocean during the 2006–07 cyclone year. The El Niño present at the beginning of the season subsided by January 2007.[6]

Most of the storms in the season occurred in the western portion of the basin.[6] From December 2006 to April 2007, a series of floods and storms affected Madagascar, including Bondo, Clovis, Favio, Gamede, Indlala, and Jaya;[8] this made it the most active season in the country since the 1999–2000 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season.[6] The series of storms and floods left 10,000 families homeless, directly affecting 9% of the country's population. These floods left 336,470 people in emergency need of food,[8][9] after the storms destroyed 76,105 ha (188,060 acres) worth of crops.[10] The World Food Programme provided meals, distributed through non-governmental organizations and local officials. This covered the needs for these families until farmers were able to rebuild and regrow their food supply, using seeds provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization.[9] The Malagasy Red Cross provided more than 10,000 residents across the country with insecticide-treated mosquito nets.[11] The series of floods diminished the country's stock of supplies from United Nations agencies,[12] spurring a declaration of a national emergency,[13] and a nearly US$19.5 million appeal for international assistance. Countries around the world donated money or supplies to help the relief effort.[9] UNICEF distributed 100 freezers and refrigerators to health facilities that bore the consequences of the active season. The agency also provided the resources to rebuild or repair 95 schools.[14]

Systems

Moderate Tropical Storm Anita

| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 26 – December 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (10-min); 996 hPa (mbar) |

A low-pressure area developed on November 26 to the north of Madagascar. Located within an area of moderate wind shear, the system consolidated its associated convection while moving southwestward. The JTWC classified the system as Tropical Cyclone 03S on November 29. That day, the disturbance turned to the south, paralleling the east coast of Mozambique while moving around a ridge. On November 30, the MFR upgraded the system to Moderate Tropical Storm Anita, estimating peak 10–minute winds of 65 km/h (40 mph). On the same day, the JTWC estimated peak 1–minute winds of 85 km/h (55 mph). Anita soon encountered higher wind shear, causing the convection to diminish over the center, and for Anita to weaken back to a tropical depression. The MFR stopped tracking Anita on December 3.[5][15][16]

While moving close to Mozambique, Anita dropped heavy rainfall in southeast Tanzania, reaching 152 mm (6.0 in) over 24 hours.[6] Heavy rainfall also occurred in the Comoros, eastern Mozambique, and northwest Madagascar, causing flash flooding.[5][17][18]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Bondo

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 15 – December 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 205 km/h (125 mph) (10-min); 930 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical disturbance developed on December 15 in the central Indian Ocean west of Diego Garcia. It strengthened into Moderate Tropical Storm Bondo on December 18. Thereafter, the storm rapidly intensified while moving westward, taking advantage of favorable atmospheric conditions. Within 18 hours of being named, Bondo intensified into tropical cyclone status, or the equivalent of a minimal hurricane. On December 20, the MFR estimated peak 10–minute sustained winds of 205 km/h (125 mph), although the JTWC estimated stronger 1–minute winds of 250 km/h (155 mph). While near peak intensity, Bondo passed just south of Agaléga island, before weakening slightly and moving through the Farquhar Group of islands belonging to the Seychelles, becoming the strongest cyclone to affect that island group in decades. Bondo turned southwestward and weakened, followed by re-intensification as it neared the northern tip of Madagascar. Bondo paralleled the coast briefly before it made landfall near Mahajanga on December 25. The storm continued southward, and was last tracked by the MFR on December 28.[5][19][20][21]

Due to its small size, Bondo's winds did not exceed 100 km/h (62 mph) on Agaléga, despite passing close by near peak intensity.[5] In the Seychelles, Bondo severely damaged buildings and vegetation on Providence Atoll.[22] High waves caused flooding elsewhere in the archipelago.[21] In Madagascar, Bondo killed 11 people when it struck the island's west coast. The storm's high winds, reaching 155 km/h (96 mph) in Mahajanga, damaged buildings and left around 20,000 people homeless.[6]

Severe Tropical Storm Clovis

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 25 – January 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 km/h (70 mph) (10-min); 978 hPa (mbar) |

Toward the end of December, the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) was active across the southern Indian Ocean. An area of thunderstorms persisted west of Diego Garcia on December 24, which wrapped around a developing circulation. On the next day, the MFR designated the system as Tropical Disturbance 4. The system drifted to the southwest, encountering an area of high wind shear on December 27, causing the circulation to become exposed and weaken. A new, larger circulation developed within the system, prompting the MFR to issue new warnings on Tropical Disturbance 5 on December 29, located southeast of Agaléga. The MFR upgraded the system to Moderate Tropical Storm Clovis on December 31 while the storm was near Tromelin Island. Clovis continued to the south-southwest, steered by a ridge to its southeast. On January 2, the MFR estimated peak 10–minute winds of 115 km/h (70 mph). The JTWC estimated slightly higher 1–minute winds of 120 km/h (75 mph), the equivalent of a minimal hurricane. Satellite imagery at this time showed a small eye in the center of the convection. While near peak intensity, Clovis made landfall in eastern Madagascar near Nosy Varika on January 3. The storm rapidly weakened over land while executing a small loop, dissipating on January 4.[5][20][23]

High waves affected the north coast of Mauritius. Clovis killed four people in Madagascar, and left 13,465 people homeless. In the country, the storm Clovis dropped heavy rainfall, reaching 213.9 mm (8.42 in) in Mananjary. The rains caused flooding, which damaged houses, power grids, and crops.[5][6] At least 1,500 ha (3,700 acres) of rice farms in Mananjary were damaged, representing about 30% of the harvest. Other damaged crops include cassava, banana, vanilla, and fruit trees.[24] The floods left roads impassable in Nosy Varika, which limited communications along with power and phone outages.[25]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Dora

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 26 – February 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 195 km/h (120 mph) (10-min); 925 hPa (mbar) |

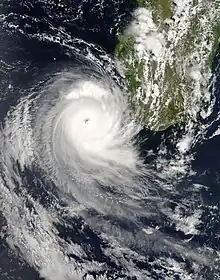

On January 26, an area of convection persisted west of Diego Garcia. That day, the MFR designated it as a tropical disturbance. Located in an area of low wind shear, the system slowly organized while moving southwestward, developing more convection and outflow over time. On January 28, the JTWC designated the system as Tropical Cyclone 10S. On the next day, the MFR upgraded the system to Moderate Tropical Storm Dora. The storm quickly intensified, and the JTWC upgraded Dora to the equivalent of a minimal hurricane on January 30. On February 1, the MFR upgraded Dora to tropical cyclone status. By that time, the cyclone was moving slowly south-southeastward between two ridges. Dora turned back to the southwest on February 2, and briefly weakened before re-intensifying, possibly the result of an eyewall replacement cycle. On February 3, the MFR upgraded Dora to an intense tropical cyclone, estimating peak 10–minute winds of 195 km/h (120 mph). The JTWC meanwhile estimated peak 1–minute winds of 215 km/h (135 mph). While at its peak intensity, Dora resembled an annular cyclone, with a large eye and a symmetrical cloud pattern. Cyclone Dora maintained peak intensity for about 12 hours before weakening due to cooler, drier air from the southeast. On February 5, Dora weakened below tropical cyclone status, as its forward movement also slowed. On February 6, Dora passed about 165 km (105 mi) east of Rodrigues. The thunderstorms around the thunderstorms dwindled due to higher wind shear, until the circulation was entirely exposed on February 9. On that day, the MFR reclassified Dora as an extratropical cyclone. The agency tracked the storm for four more days as the storm curved to the south.[5][26][27]

The Mauritius Meteorological Service first issued cyclone warnings for Rodrigues on January 31, and continued issuing warnings for the island until February 7 when the storm passed the area. Dora dropped 92 mm (3.6 in) of rainfall on the island, and gusts reached 83 km/h (52 mph).[5]

Severe Tropical Storm Enok

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 6 – February 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 km/h (70 mph) (10-min); 978 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical disturbance formed off the east coast of Madagascar on February 6. That day, the JTWC issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert, indicating rapid development of the small weather system. The nascent system moved northeastward, an unusual track caused by a trough extending northwestward from the remnants of Cyclone Dora, as well as ridge to the north. With good outflow and low wind shear, the small system intensified quickly on February 9. That day, the MFR upgraded the system to Severe Tropical Storm Enok, and the JTWC classified the storm as Tropical Cyclone 13S. Early on February 10, the MFR estimated peak winds of 115 km/h (70 mph), although it is possible the storm was stronger, based on the appearance of an eye-like feature in the convection. That day, Enok passed just north of St. Brandon, which reported a calm lasting a few minutes. The storm moved quickly to the southeast and weakened due to higher wind shear and dry air. Late on February 10, Enok passed just northeast of Rodrigues. On the next day, the storm weakened to into a tropical depression and turned back to the west. The MFR discontinued advisories on February 13.[4][5][28][29]

On St. Brandon, Enok produced wind gusts of 160 km/h (99 mph), strong enough to damage iron sheets and a window pane. Rainfall on the island reached 118 mm (4.6 in). Later, Enok produced wind gusts of 142 km/h (88 mph) on Rodrigues; the storm dropped 147 mm (5.8 in) of rainfall.[5]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Favio

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 11 – February 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 195 km/h (120 mph) (10-min); 925 hPa (mbar) |

Cyclone Favio developed as a tropical disturbance on February 11 to the southwest of Diego Garcia. It moved southwestward due to a ridge to its southeast, gradually organizing amid favorable conditions. The JTWC first classified the system as Tropical Cyclone 14S on February 14. A day later, the MFR upgraded the system to Moderate Tropical Storm Favio, and later that day, the storm passed about 120 km (75 mi) northwest of Rodrigues. The ridge to its south built westward, causing Favio to turn westward. On February 19, the MFR upgraded the storm to tropical cyclone status while Favio was passing south of Madagascar. The cyclone intensified further as it turned to the northwest in the Mozambique Channel. Late on February 20, the MFR estimated that Favio attained peak winds of 195 km/h (120 mph), making it an intense tropical cyclone. Meanwhile, the JTWC estimated peak 1–minute winds of 220 km/h (135 mph). Favio weakened slightly before making landfall in southeastern Mozambique on February 22 near Vilankulo. This made Favio the first cyclone on record to strike Mozambique after moving south of Madagascar. The cyclone rapidly weakened over land, and the MFR discontinued advisories on February 23 when the storm was near the Mozambique/Zimbabwe border.[4][6][26][30]

On Rodrigues, the cyclone produced 114 km/h (71 mph) wind gusts, as well as heavy rainfall reaching 217.6 mm (8.57 in).[5] The storm brushed the southern coast of Madagascar, producing heavy rainfall that blocked roads.[31] In Mozambique, Favio killed 10 people and caused additional deadly flooding that had affected the country since January.[32] Damage from Favio and the flooding were estimated at US$71 million.[33] The storm damaged about 130,000 homes, which displaced over 33,000 people, and also damaged 130 schools, widespread areas of crops, and power grids.[34][35][36] Favio dropped heavy rainfall across southern Africa, causing flooding in eastern Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.[6][37][38]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Gamede

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 19 – March 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (10-min); 935 hPa (mbar) |

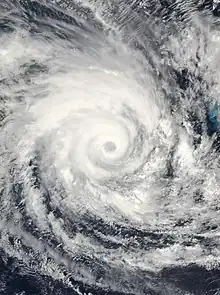

A tropical disturbance developed within the ITCZ on February 19 southeast of Diego Garcia. Steered by a ridge to the south, the system moved westward and gradually organized amid favorable conditions. On February 21, the MFR upgraded the system to Moderate Tropical Storm Gamede, and the JTWC initiated advisories on Tropical Cyclone 15S. Gamede gradually intensified, reaching tropical cyclone intensity on February 23. The track shifted to the west-southwest, and the outer rainbands began affecting the Mascarene Islands on February 24. A day later, the storm stalled to the north of Réunion, trapped between ridges to the east-northeast and to the south. During this time, Gamede attained peak 10–minute winds of 165 km/h (105 mph), according to the MFR. The JTWC estimated peak 1–minute winds of 195 km/h (120 mph). The cyclone passed west of Réunion on February 27, after beginning a steady motion to the south-southwest. By that time, Gamede had weakened due to upwelling cooler waters, and later weakened further due to stronger wind shear. On March 2, the MFR reclassified Gamede as an extratropical cyclone, and the agency tracked the storm for four more days as the circulation again stalled before drifting westward.[5][28][4][39]

Cyclone Gamede passed near St. Brandon, where its 160 km/h (99 mph) wind gusts damaged a few windows.[5] The cyclone left two ships missing near St. Brandon, with a combined crew of 16 people.[40] When the storm stalled for a few days, it resulted in a prolonged period of heavy rainfall and high tides for the Mascarene Islands. On Mauritius, wind gusts reached 158 km/h (98 mph);[5] the storm killed two people on the island and left 60% of islanders without power.[41] Effects were worse on neighboring Réunion, with two fatalities, and monetary damage estimated at over €165 million (US$120 million).[42][43] Gamede produced wind gusts of 205 km/h (125 mph) alongside historic rainfall totals on Réunion. At Commerson Crater, Gamede broke numerous worldwide records for tropical cyclone rainfall, including for three days, when 3,930 mm (155 in) was recorded, and for every duration through nine days, when 5,512 mm (217.0 in) was recorded.[44][45] The heavy rains produced flooding that wrecked crops and damaged infrastructure.[41] The storm washed out a bridge over the Rivière Saint-Étienne, connecting Saint-Louis and Saint-Pierre.[46] Later, Gamede brushed the east coast of Madagascar with winds and rainfall,[47] In the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal, high waves closed beaches, roads, and the port of Port of Durban.[48]

Tropical Cyclone Humba

| Tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 21 (Entered basin) – February 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 km/h (85 mph) (10-min); 960 hPa (mbar) |

The BoM began monitoring a tropical low on February 19 to the northwest of the Cocos Islands. With low wind shear and good outflow, the low's deep convection pulsed around a broad, but well-defined circulation. The MFR began monitoring the system on February 20 while it was still in the Australian basin. A large ridge over western Australia steered the low to the west-southwest, bringing it into the south-west Indian Ocean on February 21. On that day, the MFR classified the system as Tropical Depression 11, and the JTWC classified it as Tropical Cyclone 16S. On February 23 upgraded it to Moderate Tropical Storm Humba, after the system organized further. The track gradually shifted to the south around the western periphery of the ridge. Humba attained tropical cyclone status on February 24, and reached peak winds the next day of 140 km/h (85 mph), according to the MFR; the JTWC estimated slightly higher peak winds of 150 km/h (95 mph).[5][28][49]

After peak intensity, the cyclone encountered an upper-level trough that increased wind shear in the region. This caused Humba to weaken quickly as its convection dislocated from the circulation. Late on February 25, it fell below tropical cyclone status while entering cooler waters. On February 26, the MFR declared Humba an extratropical cyclone. The storm continued generally southward for two more days until it stalled for a day, blocked by a ridge to its south. The former Cyclone Humba turned to the southeast and was tracked by the MFR until March 4, as it moved across the southern Indian Ocean, back into the Australian region.[28][5][49]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Indlala

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 10 – March 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 175 km/h (110 mph) (10-min); 935 hPa (mbar) |

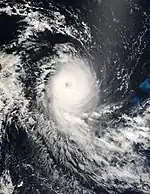

The intertropical convergence zone spawned an area of convection southwest of the Chagos on March 9. A day later, the MFR designated the system as Tropical Disturbance 12, which moved generally westward. On March 11, the MFR upgraded the system to Tropical Depression 12, and to Moderate Tropical Storm Indlala a day later. the JTWC designated the storm as Tropical Cyclone 19S. Indlala gradually intensified, reaching tropical cyclone status on March 13, and becoming an intense tropical cyclone a day later. The MFR estimated peak 10–minute winds of 175 km/h (110 mph), and a minimum pressure of 935 mbar (27.6 inHg). The JTWC's intensity estimate was higher, with peak 1–minute winds of 220 km/h (135 mph). Early on March 15, the cyclone made landfall in northeastern Madagascar on the Masoala Peninsula near Antalaha, still at its peak intensity according to the MFR. Indlala rapidly weakened over land and turned southward, eventually re-emerging into the Indian Ocean on March 18; it was last noted by the MFR on March 19.[5][50][51]

Cyclone Indlala produced strong winds in northeastern Madagascar, with a 245 km/h (152 mph) gust recorded at Antalaha. The cyclone also dropped heavy rainfall in the eastern portion of the country, reaching 585.4 mm (23.05 in) over 48 hours in Antsohihy in northern Madagascar.[6] These rains flooded a 131,700 km2 (50,800 sq mi) area of northern Madagascar, causing the worst floods in Sofia Region since 1949.[52] Indlala killed 150 people across Madagascar and injured another 126.[6] Damage in the country was estimated at over US$240 million,[9] with around 54,000 houses damaged or destroyed,[9] leaving 188,331 people homeless.[6] The storm also damaged 228 schools and 71 hospitals.[9] Throughout Madagascar, the cyclone wrecked about 90,000 ha (220,000 acres) worth of crops.[52]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Jaya

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 26 – April 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (10-min); 935 hPa (mbar) |

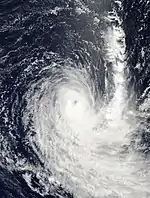

An area of convection persisted southeast of the Chagos on March 26. It consolidated into Tropical Disturbance 14 on March 29 as it moved westward, steered by a ridge to the south. A day later, the system intensified into Moderate Tropical Storm Jaya, taking advantage of favorable conditions including low wind shear. Also on March 30, the JTWC classified the storm as Tropical Cyclone 22S, and later that day Jaya began to rapidly intensify; over 24 hours, its pressure dropped by 50 hPa (1.4765 inHg). Jaya attained tropical cyclone status early on March 31, and at 18:00 UTC that day it attained peak winds of 185 km/h (115 mph), according to the MFR; this made it the sixth intense tropical cyclone of the season. The JTWC estimated even higher maximum sustained winds on April 1, estimating 1–minute winds of 205 km/h (125 mph). On the same day, Jaya passed about 165 km north of St. Brandon, which recorded a 72 km/h (45 mph) wind gust and 11.7 mm (0.46 in) of precipitation.[5][50][53]

After Jaya reached peak intensity, its inner convection weakened due to dry air, and it fell below intense tropical cyclone status. On April 2, a small eye re-developed in the center of the storm, signaling a temporary period of re-intensification. Jaya again weakened as it approached eastern Madagascar, and it moved ashore about 25 km (15 mi) south of Sambava, with winds of around 135 km/h (85 mph). It struck Madagascar less than three weeks after Indlala's deadly landfall, at an landfall location north of Indlala, which complicated relief efforts for the earlier storm.[5][9][50][53] Jaya dropped heavy rainfall in the eastern portion of the country, with a peak 24 hour rainfall total of 216.1 mm (8.51 in) at Toamasina.[6] This resulted in significant flooding in the Sofia and Diana regions of the country.[9] Wind gusts reached 125 km/h (78 mph) at Sambava and Antalaha. Jaya killed one person in the country, and injured two others, with 8,015 people left homeless.[6]

Jaya rapidly deteriorated as it continued westward across the island, emerging into the Mozambique Channel as a tropical disturbance on April 4. Conditions were unfavorable for re-strengthening, such as strong wind shear. The circulation of Jaya passed south of the Comoros and moved southwestward along the Mozambique coastline. It turned to the southeast away from the coast on April 6 and later moved back to the northwest. On April 8, the MFR stopped tracking the system. The circulation soon after was absorbed by a developing subtropical cyclone.[5][50][53][3]

Subtropical Depression 15

| Subtropical depression (MFR) | |

| |

| Duration | April 9 – April 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (10-min); 994 hPa (mbar) |

A non-tropical low originated in the southern Mozambique Channel on April 9, located off the east coast of Mozambique. The low absorbed the circulation of former Cyclone Jaya, intensifying gradually while moving to the southeast and later south. The MFR classified the system as a tropical depression on April 10, and that day the system passed west of Europa Island. The agency reclassified the system as a subtropical depression with gale-force winds on April 11, estimating peak winds of 95 km/h (60 mph). It was a small cyclone, with gale-force winds extending only 95 km (65 mi) from the center. The storm accelerated to the southeast, and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on April 12, which the MFR tracked for another day.[3][54]

Other storms

The first tropical system in the season originated from an area of convection that developed northwest of Diego Garcia on October 18. The system had defined outflow and a tight circulation, spurring the JTWC to issue a TCFA. On October 19, the MFR classified it as Tropical Disturbance 1. Environmental conditions were only marginally favorable, and the disturbance drifted to the southwest without much organization. After passing southeast of the Seychelles, the disturbance passed north of Madagascar. The MFR last issued advisories on the system on October 23.[55]

In early January, an area of convection formed in the Mozambique Channel. The MFR classified it as Tropical Disturbance 6 on January 8, but the system failed to intensify further. The MFR discontinued advisories that day, as the disturbance would soon move over southwestern Madagascar.[26]

The MFR designated Tropical Disturbance 13 for a weather system on March 13, located southwest of the Chagos. The disturbance drifted to the south, failing to intensify beyond winds of 45 km/h (30 mph). After the disturbance turned back to the northwest, the MFR discontinued advisories on March 17.[50]

Storm names

A tropical disturbance is named when it reaches moderate tropical storm strength. If a tropical disturbance reaches moderate tropical storm status west of 55°E, then the Sub-regional Tropical Cyclone Advisory Centre in Madagascar assigns the appropriate name to the storm. If a tropical disturbance reaches moderate tropical storm status between 55°E and 90°E, then the Sub-regional Tropical Cyclone Advisory Centre in Mauritius assigns the appropriate name to the storm. A new annual list is used every year so no names are retired. These were the names used this year.[56]

|

|

Season effects

This table lists all the storms that developed in the Southern Hemisphere during the 2006–2007 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season. It includes their intensity, duration, name, landfalls, deaths, and damages. All data is taken from Météo-France.

| Name | Dates | Peak intensity | Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Wind speed | Pressure | ||||||

| One | October 19 — 23 | Tropical disturbance | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 1002 hPa (29.59 inHg) | None | None | None | [57][58] |

| Anita | November 26 – December 4 | Moderate Tropical Storm | 65 km/h (40 mph) | 996 hPa (29.41 inHg) | Madagascar, Mozambique | |||

| Bondo | December 15–28 | Intense Tropical Cyclone | 205 km/h (125 mph) | 930 hPa (27.46 inHg) | Madagascar, Mozambique | 11 | [6] | |

| 04 | December 22–28 | Tropical Disturbance | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 1000 hPa (29.53 inHg) | None | |||

| Clovis | December 29 – January 4 | Severe tropical storm | 115 km/h (70 mph) | 978 hPa (28.88 inHg) | Madagascar | 4 | [6] | |

| 06 | January 5–8 | Tropical Disturbance | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 999 hPa (29.50 inHg) | None | |||

| Dora | January 26 – February 8 | Intense Tropical Cyclone | 195 km/h (120 mph) | 925 hPa (27.32 inHg) | Rodrigues | |||

| Enok | February 6–13 | Severe tropical storm | 115 km/h (70 mph) | 978 hPa (28.88 inHg) | None | |||

| Favio | February 11–23 | Intense Tropical Cyclone | 195 km/h (120 mph) | 925 hPa (27.32 inHg) | Mozambique, Madagascar | $71 million | 10 | [32][33] |

| Gamede | February 19 – March 1 | Intense Tropical Cyclone | 165 km/h (105 mph) | 935 hPa (27.61 inHg) | Mascarene Islands (Direct hit, no landfall) | $120 million | 4 | [41][42][43] |

| Humba | February 20–26 | Tropical Cyclone | 140 km/h (85 mph) | 960 hPa (28.35 inHg) | None | |||

| Indlala | March 9–19 | Intense Tropical Cyclone | 175 km/h (110 mph) | 935 hPa (27.61 inHg) | Madagascar | $240 million | 150 | [6][9] |

| 13 | March 13–17 | Tropical Disturbance | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 1000 hPa (29.53 inHg) | None | |||

| Jaya | March 26 – April 8 | Intense Tropical Cyclone | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 935 hPa (27.61 inHg) | Madagascar | 1 | [6] | |

| 15 | April 9–12 | Subtropical Depression | 95 km/h (60 mph) | 994 hPa (29.35 inHg) | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||

| 15 systems | October 19 – April 12 | 195 km/h (120 mph) | 925 hPa (27.32 inHg) | $431 million | 180 | |||

See also

References

- ↑ The 2006-2007 Summer Season Outlook (Report). Mauritius Meteorological Services. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ↑ Philippe Caroff; et al. (June 2011). Operational procedures of TC satellite analysis at RSMC La Réunion (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Gary Padgett (May 26, 2007). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary April 2007". Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 2007 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Technical Report CS 28 Cyclone Season of the South West Indian Ocean 2006 – 2007 (PDF) (Report). Mauritius Meteorological Services. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee for the South-West Indian Ocean Eighteenth Session (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ↑ Teo Blašković (March 6, 2019). "Record Southwest Indian Ocean tropical cyclone season". Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- 1 2 Madagascar: After season of cyclones, Red Cross works to prevent malaria. American Red Cross (Report). July 27, 2007. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020 – via ReliefWeb.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Southern Africa: New money to mitigate disaster. The New Humanitarian (Report). July 24, 2008. Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020 – via ReliefWeb.

- ↑ Madagascar: Cyclone Indlala – Situation Report No. 7. United Nations Country Team in Madagascar (Report). May 4, 2007. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020 – via ReliefWeb.

- ↑ Madagascar: After season of cyclones, Red Cross works to prevent malaria. American Red Cross (Report). July 27, 2007. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ↑ UN agencies and NGO partners seek $9.6 million for Madagascar (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. March 16, 2007. Archived from the original on March 23, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ↑ "Cyclone incurs heavy losses in Madagascar". Xinhua. March 19, 2007. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020 – via ReliefWeb.

- ↑ UNICEF External Situation Report Madagascar (PDF). UNICEF (Report). June 28, 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020 – via ReliefWeb.

- ↑ Gary Padgett (March 3, 2007). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary November 2006". Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Anita (2006330S06049). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ↑ Weather Hazards Impacts Assessment for Africa: December 7 - 13, 2006 (Report). Famine Early Warning System Network. December 6, 2006. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019 – via ReliefWeb.

- ↑ "Southern African Humanitarian Crisis Update - December 2006". UN Regional Inter-Agency Coordination and Support Office. December 31, 2006. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019 – via ReliefWeb.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Bondo (2006350S07071). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 25, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- 1 2 Gary Padgett (March 4, 2007). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary December 2006". Archived from the original on January 25, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- 1 2 Denis hang Seng; Richard Guillande (July 2008). Disaster risk profile of the Republic of Seychelles (PDF) (Report). PreventionWeb. pp. 45, 46. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 29, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ↑ Adrian Skerrett (January 8, 2007). "Island Conservation-A serious blow". Seychelles Nation. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Clovis (2006364S12058). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ↑ Madagascar: Cyclone Clovis DREF operation no. MDRMG001 final report. International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (Report). December 17, 2007. Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019 – via ReliefWeb.

- ↑ Madagascar: Cyclone Clovis DREF Bulletin no. MDRMG001. International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (Report). January 19, 2007. Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019 – via ReliefWeb.

- 1 2 3 Gary Padgett. "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary January 2007". Archived from the original on April 13, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Dora (2007027S07069). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Gary Padgett (March 28, 2007). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary February 2007". Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Enok (2007037S19050). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Favio (2007043S11071). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ↑ "Cyclone Favio rampages through coastal town". IRN Africa. February 22, 2007. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- 1 2 "Cyclone may hit tourist resorts". Associated Press. February 25, 2007. The Oklahoman. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- 1 2 "Mozambique: Floods and Cyclone Fact Sheet #1 (FY) 2007". March 22, 2007. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2020 – via ReliefWeb.

- ↑ "Coastal towns hard at work after Cyclone Favio". UNICEF. February 28, 2007. Archived from the original on August 22, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Mozambique: Floods and Cyclone Fact Sheet #1 (FY) 2007". Relief Web. March 22, 2007. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Mozambique: Cyclone Favio rampages through coastal town". IRIN Africa. February 22, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Favio takes its wrath out on Mozambique". The Zambienen. March 8, 2007. Archived from the original on May 5, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Cyclone Favio Strikes Mozambique". Earthweek. March 2, 2007. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Gamede (2007050S16079). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ↑ "Saison Cyclonique" (PDF) (217). Météo-France. December 2007. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 "Cyclone Leaves Dead And Across Slew Of Indian Ocean Islands". Agence France-Presse. February 25, 2007. Space Daily. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- 1 2 "Gamède fait deux morts à la Réunion". Agence France-Presse. February 28, 2007. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2020 – via Le Figaro.

- 1 2 "L'évaluation préliminaire des risques d'inondation" (PDF) (in French). Réunion Regional Directorate for the Environment, Planning and Housing. 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ↑ "Recent Investigations". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ↑ Hubert Quetelard; Pierre Bessemoulin; Randall S. Cerveny; Thomas C. Peterson; Andrew Burton; Yadowsun Boodhoo. World record rainfalls (72-hour and four-day accumulations) at Cratère Commerson, Réunion Island, during the passage of Tropical Cyclone Gamede (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ↑ "Opening of the bridge over the Saint-Étienne River". Vinci. July 12, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ↑ "Africa: Weather Hazards Assessments for March 1–7, 2007". Famine Early Warning System Network. February 28, 2007. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ↑ Ian Hunter. "The Legacy of Tropical Cyclone 'Gamede'". SA Weather Service. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- 1 2 Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Tropical Cyclone Humba (2007052S10093). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gary Padgett (May 26, 2007). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary March 2007". Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Very Intense Tropical Cyclone Indlala (2007066S12066). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- 1 2 "2007 Global Register of Major Flood Events". Dartmouth Flood Observatory. May 1, 2008. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Intense Tropical Cyclone Jaya (2007085S11085). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2007 Tropical Depression Not_Named (2007100S22037). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ Gary Padgett (February 6, 2007). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary October 2006". Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ↑ RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee for the South-West Indian Ocean Seventeenth Session Final Report (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. 2005. Appendix VI. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ↑ Padgett, Gary. "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Tracks October 2006". Archived from the original on February 11, 2006. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ↑ Padgett, Gary. Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary October 2005 (Report). Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

External links

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) Archived March 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Météo France (RSMC La Réunion)

- World Meteorological Organization