| Réunion giant tortoise | |

|---|---|

| |

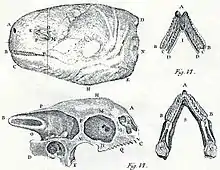

| 1792 sketch of a living specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Testudinidae |

| Genus: | †Cylindraspis |

| Species: | †C. indica |

| Binomial name | |

| †Cylindraspis indica Schneider, 1783 | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The Reunion giant tortoise (Cylindraspis indica) is an extinct species of giant tortoise in the family Testudinidae. It was endemic to Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean.[1]

This giant tortoise was numerous in the 17th and early 18th centuries. They were killed in vast numbers by European sailors, and finally became extinct in the 1840s.[3]

Description

The Réunion giant tortoise was 50 to 110 cm long. It was the largest of the Cylindraspis giant tortoise species of the Mascarenes. It was roughly the same size as modern Aldabra giant and Galapagos giant tortoises, though it was a longer and more elongated animal.[4]

It had long legs and a long neck which supported a large head with powerful, strongly-serrated jaws. The species was sexually dimorphic, in that males were noticeably larger than females.

It was also a highly variable species. A problem arises when identifying this species because it appears there were domed variants as well as saddle-backed variants.[3]

Distribution

This species was endemic to Réunion. On this island it was naturally extremely numerous, and its vast herds provided an important role in the health and rejuvenation of the indigenous forests.[5][6]

Extinction

These giant tortoises were very friendly, curious, and had no fear of humans. They were, therefore, easy prey for the first inhabitants of the island, and were slaughtered in vast numbers to be burnt for fat and oil, or to be used as food (for humans or pigs). Large numbers were also stacked into the holds of passing ships, as food supplies for sea trips.[7][8]

In addition, invasive species, such as pigs, cats, and rats, destroyed the eggs and hatchlings of the giant tortoises.

Coastal populations were completely decimated by the 18th century. It was presumed extinct in much of the island since 1800, with the last specimen observed in Upper Cilaos. The last few animals survived in the highlands until the 1840s.[3][9][10]

References

- 1 2 World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Cylindraspis indica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T6061A12383518. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T6061A12383518.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Fritz Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 277. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. ISSN 1864-5755. S2CID 87809001.

- 1 2 3 Petermaas.nl

- ↑ Cheke AS, Bour R: Unequal struggle—how humans displaced the tortoise's dominant place in island ecosystems. In: Gerlach, J., ed. Western Indian Ocean Tortoises: biodiversity. 2014.

- ↑ C.Stanford: The Last Tortoise: A Tale of Extinction in Our Lifetime. Belknap. 2010. ISBN 9780674049925

- ↑ C.Chambers: A Sheltered Life: The Unexpected History of the Giant Tortoise. Oxford University Press. 2007. ISBN 9780195223965

- ↑ W. Rotschild: . On the gigantic land tortoises of the Seychelles and Aldabra-Madagascar group with some notes on certain forms of the Mascarene group. 1915. Novitates Zoologicae 22.

- ↑ P Stoddard, J Peake, C Gordon, R Burleigh: Historical records of Indian Ocean giant tortoise populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 1979. 286B

- ↑ J. Gerlach: Giant tortoises of the Indian Ocean. The genus Dipsochelys inhabiting the Seychelles Islands and the extinct giants of Madagascar and the Mascarenes. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt. 2004.

- ↑ D.Day: The Doomsday Book of Animals. Ebury Press, London. 1981. ISBN 0852231830.