- European Union member states

-

5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

- Non–EU member states

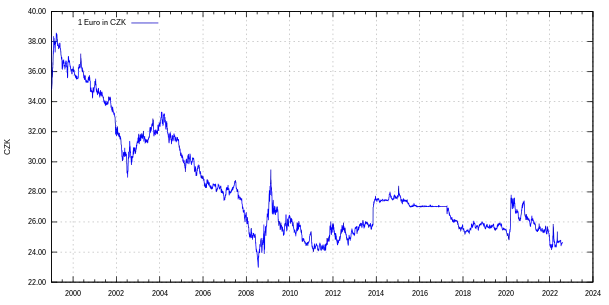

The Czech Republic is bound to adopt the euro in the future and to join the eurozone once it has satisfied the euro convergence criteria by the Treaty of Accession since it joined the European Union (EU) in 2004. The Czech Republic is therefore a candidate for the enlargement of the eurozone and it uses the Czech koruna as its currency, regulated by the Czech National Bank, a member of the European System of Central Banks, and does not participate in European Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II).

Although the Czech Republic is economically well positioned to adopt the euro, following the European debt crisis there has been considerable opposition among the public to the adoption of the euro currency.[1] There is no target date by the government for joining the ERM II or adopting the euro.[2] The cabinet that was formed following the 2017 legislative election did not plan to proceed with euro adoption within its term,[3] and this policy was continued by the succeeding cabinet formed after the 2021 election.[4]

History

European Union accession and 2000s

The European Union membership referendum in 2003 approved the country's accession with 77.3% in favour, and in 2004 the Czech Republic joined the EU.[5]

Since joining the EU in May 2004, the Czech Republic has adopted fiscal and monetary policies that aim to align its macroeconomic conditions with the rest of the European Union. Initially, the Czech Republic planned to adopt the euro as its official currency in 2010, however evaluations in 2006 found this date to be unlikely and the target date was postponed indefinitely.[6] In February 2007, the Finance Minister said 2012 was a "realistic" date,[7] but by November 2007 this was said to be too soon.[8] In August 2008, an assessment said that adoption was not expected before 2015 due to political reluctance on the subject.[9] However, in October 2009, the then Finance Minister, Eduard Janota, stated that 2015 was no longer realistic.[10] In June 2008, the Central bank governor Zdeněk Tůma speculated about 2019.[11]

In late 2010 a discussion arose within the Czech government, partially initiated by then President Václav Klaus, a well known eurosceptic, over negotiating an opt-out from joining the eurozone. Czech Prime Minister Petr Nečas later stated that no opt-out was required because the Czech Republic could not be forced to join the ERM II and thus could decide if or when to fulfil one of the necessary criteria to join the eurozone, an approach similar to the one taken by Sweden. Nečas also stated that his cabinet would not decide upon joining the euro during its term.[12][13]

2010s

The European debt crisis further decreased the Czech Republic's interest in joining the eurozone.[14] Nečas said that since the conditions governing the eurozone had significantly changed since their accession treaty was ratified, he believed that Czechs should be able to decide by a referendum whether to join the eurozone under the new terms.[15] One of the government's junior coalition parties, TOP09, was opposed to a euro referendum.[16][17]

In April 2013, the Czech Ministry of Finance stated in its Convergence Programme delivered to the European Commission that the country had not yet set a target date for euro adoption and would not apply for ERM II membership in 2013. Their goal was to limit their time as an ERM II member, prior to acceding to the eurozone, to as brief a period as possible.[18] On 29 May 2013 Miroslav Singer, the Governor of the Czech National Bank (the Czech Republic's central bank) stated that in his professional opinion the Czech Republic will not adopt the euro before 2019.[19] In December 2013, the Czech government approved a recommendation from the Czech National Bank and Ministry of Finance against setting a formal target date for euro adoption or joining ERM II in 2014.[20]

Miloš Zeman, who was elected President of the Czech Republic in early 2013, supports euro adoption by the Czech Republic, though he also advocates a referendum on the decision.[21][22] Shortly after taking office in March 2013, Zeman suggested that the Czech Republic would not be ready for the switch for at least five years.[23] Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka, from the Social Democrats, stated on 25 April 2013, prior to his party's election victory that October, that he was "convinced that the government that will be formed after next year's election should set the euro entry date" and that "1 January 2020 could be a date to look at".[24][25] Shortly after being sworn into the new Cabinet in January 2014, Czech Foreign Minister Lubomír Zaorálek stated that the country should join the eurozone as soon as possible.[26] The opposition TOP 09 had also run on a platform in the 2013 parliamentary election, that called for the Czech Republic to adopt the euro between 2018 and 2020.[27] In line with this, the governor of the Czech National Bank, having an advisory role towards the government about the timing of euro adoption, described 2019 as the earliest possible euro entry date.[28]

In April 2014, the Czech Ministry of Finance clarified in its Convergence Programme delivered to the European Commission, that the country had not yet set a target date for euro adoption and would not apply for ERM-II membership in 2014. Their goal was to limit their time as an ERM-II member, prior to acceding to the eurozone, to as brief a period as possible. Moreover, it was the opinion of the previous government that: "the fiscal problems of the eurozone, together with continued difficulty to predict the development of the monetary union, do not create a favorable environment for the future adoption of the euro."[29]

Zeman stated in June 2014 that he hoped his country would adopt the euro as soon as 2017, arguing that adoption would be beneficial for the Czech economy overall.[30] The opposition ODS party responded by running a campaign for Czechs to sign an anti-euro petition, handed over to the Czech Senate in November 2014, but viewed by political commentators as not having any impact on changing the government's policy to adopt the euro in the medium-term without holding a referendum on it.[31]

In December 2014, the Czech government approved a joint recommendation from the Czech National Bank and Ministry of Finance, against setting a formal target date for euro adoption or joining ERM-II during the course of 2015.[32] In March 2015, the ruling Czech Social Democratic Party adopted a policy of striving to gather political support to adopt the euro by 2020.[33] In April 2015, the coalition government announced it had agreed to not set a euro adoption target and not to enter ERM-2 until after the next legislative election scheduled for 2017, making it unlikely that the Czech Republic will adopt the euro before 2020. In addition, the coalition government agreed that if it wins re-election it would set a deadline of 2020 to agree on a specific euro adoption roadmap.[34] In June 2015, finance minister Andrej Babiš suggested a nonbinding public referendum on euro adoption.[35] The Andrej Babiš' Cabinet that was formed following the 2017 legislative election does not plan to proceed with euro adoption within its term.[3]

2020s

Petr Fiala's cabinet that emerged from the 2021 legislative election does not intend to adopt euro within its term either, calling the adoption "disadvantageous" for the Czech Republic.[4]

In 2023 President-elect Pavel said, that as a citizen he supports Euro adoption.[36]

Euro use

Selected chain stores in the Czech Republic accept payments in euros, and return change in Czech koruna.[37]

Opinion polls

The following are polls on the question of whether the Czech Republic should abolish the koruna and adopt the euro.

| Date (survey taken) | Date (when published) | Yes | No | Undecided | Conducted by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 2004 | October 2004 | 52% | 48% | 0% | Eurobarometer[38] |

| September 2005 | November 2005 | 49% | 51% | 0% | Eurobarometer[39] |

| December 2005 | January 2011 | 44% | 56% | 0% | STEM[40] |

| April 2006 | June 2006 | 56% | 44% | 0% | Eurobarometer[41] |

| June 2006 | January 2011 | 46% | 54% | 0% | STEM[40] |

| September 2006 | November 2006 | 56% | 44% | 0% | Eurobarometer[42] |

| November 2006 | January 2011 | 47% | 53% | 0% | STEM[40] |

| April 2007 | November 2007 | 57% | 43% | 0% | Eurobarometer[43] |

| September 2007 | November 2007 | 56% | 44% | 0% | Eurobarometer[43] |

| May 2008 | July 2008 | 54% | 46% | 0% | Eurobarometer[44] |

| May 2009 | 2009 | 61% | 39% | 0% | Eurobarometer[45] |

| September 2009 | 2009 | 48% | 52% | 0% | Eurobarometer[46] |

| September 2010 | January 2011 | 30% | 70% | 0% | STEM[40] |

| September 2010 | December 2010 | 41% | 59% | 0% | Eurobarometer[47] |

| January 2011 | 2011 | 22% | 78% | 0% | STEM[40] |

| May 2011 | August 2011 | 33% | 67% | 0% | Eurobarometer[48] |

| November 2011 | July 2012 | 13% | 82% | 5% | Eurobarometer[49] |

| April 2012 | July 2012 | 13% | 81% | 6% | Eurobarometer[50] |

| April 2013 | June 2013 | 14% | 80% | 6% | Eurobarometer[51] |

| April 2014 | June 2014 | 16% | 77% | 7% | Eurobarometer[52] |

| April 2015 | May 2015 | 24% | 69% | 7% | CVVM[53] |

| April 2015 | May 2015 | 29% | 70% | 1% | Eurobarometer[54] |

| April 2016 | May 2016 | 17% | 78% | 5% | CVVM[55] |

| April 2016 | May 2016 | 29% | 70% | 1% | Eurobarometer[56] |

| April 2017 | May 2017 | 21% | 72% | 7% | CVVM[57] |

| April 2017 | May 2017 | 29% | 70% | 1% | Eurobarometer[58] |

| April 2018 | May 2018 | 20% | 73% | 7% | CVVM[59] |

| April 2018 | May 2018 | 33% | 66% | 1% | Eurobarometer[60] |

| April 2019 | May 2019 | 20% | 75% | 5% | CVVM[61] |

| April 2019 | June 2019 | 39% | 60% | 1% | Eurobarometer[62] |

| June 2020 | July 2020 | 34% | 63% | 3% | Eurobarometer[63] |

| May 2021 | July 2021 | 33% | 67% | 0% | Eurobarometer[64] |

| April 2022 | June 2022 | 43% | 55% | 2% | Eurobarometer[65] |

| April 2023 | June 2023 | 47% | 52% | 1% | Eurobarometer[66] |

| May 2023 | July 2023 | 22% | 73% | 5% | CVVM[67] |

Eurobarometer chart

- Public support for the euro in the Czech Republic by each Eurobarometer survey[68]

Adoption status

The 1992 Maastricht Treaty originally required that all members of the European Union join the euro once certain economic criteria are met. The Czech Republic meets two of the five conditions for joining the euro as of June 2022; their inflation rate, not being a member of the European exchange rate mechanism, and the incompatibility of its domestic legislation are the conditions not met.

| Assessment month | Country | HICP inflation rate[69][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[70] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[71][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget deficit to GDP[72] | Debt-to-GDP ratio[73] | ERM II member[74] | Change in rate[75][76][nb 3] | |||||

| 2012 ECB Report[nb 4] | Reference values | Max. 3.1%[nb 5] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

None open (as of 31 March 2012) | Min. 2 years (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2011) |

Max. 5.80%[nb 7] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Yes[77][78] (as of 31 Mar 2012) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2011)[79] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2011)[79] | |||||||

| 2.7% | Open | No | 2.7% | 3.54% | No | |||

| 3.1% | 41.2% | |||||||

| 2013 ECB Report[nb 8] | Reference values | Max. 2.7%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2013) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2012) |

Max. 5.5%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Yes[80][81] (as of 30 Apr 2013) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2012)[82] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2012)[82] | |||||||

| 2.8% | Open | No | -2.3% | 2.30% | Unknown | |||

| 4.4% | 45.8% | |||||||

| 2014 ECB Report[nb 10] | Reference values | Max. 1.7%[nb 11] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2014) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2013) |

Max. 6.2%[nb 12] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Yes[83][84] (as of 30 Apr 2014) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2013)[85] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2013)[85] | |||||||

| 0.9% | Open (Closed in June 2014) | No | -3.3% | 2.21% | No | |||

| 1.5% | 46.0% | |||||||

| 2016 ECB Report[nb 13] | Reference values | Max. 0.7%[nb 14] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

None open (as of 18 May 2016) | Min. 2 years (as of 18 May 2016) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2015) |

Max. 4.0%[nb 15] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

Yes[86][87] (as of 18 May 2016) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2015)[88] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2015)[88] | |||||||

| 0.4% | None | No | 0.9% | 0.6% | No | |||

| 0.4% | 41.1% | |||||||

| 2018 ECB Report[nb 16] | Reference values | Max. 1.9%[nb 17] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

None open (as of 3 May 2018) | Min. 2 years (as of 3 May 2018) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2017) |

Max. 3.2%[nb 18] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

Yes[89][90] (as of 20 March 2018) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2017)[91] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2017)[91] | |||||||

| 2.2% | None | No | 2.6% | 1.3% | No | |||

| -1.6% (surplus) | 34.6% | |||||||

| 2020 ECB Report[nb 19] | Reference values | Max. 1.8%[nb 20] (as of 31 Mar 2020) |

None open (as of 7 May 2020) | Min. 2 years (as of 7 May 2020) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2019) |

Max. 2.9%[nb 21] (as of 31 Mar 2020) |

Yes[92][93] (as of 24 March 2020) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2019)[94] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2019)[94] | |||||||

| 2.9% | None | No | -0.1% | 1.5% | No | |||

| -0.3% (surplus) | 30.8% | |||||||

| 2022 ECB Report[nb 22] | Reference values | Max. 4.9%[nb 23] (as of April 2022) |

None open (as of 25 May 2022) | Min. 2 years (as of 25 May 2022) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2021) |

Max. 2.6%[nb 23] (as of April 2022) |

Yes[95][96] (as of 25 March 2022) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2021)[95] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2021)[95] | |||||||

| 6.2% | None | No | 3.1% | 2.5% | No | |||

| 5.9% (exempt) | 41.9% | |||||||

- Notes

- ↑ The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- ↑ The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- ↑ The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2012.[77]

- ↑ Sweden, Ireland and Slovenia were the reference states.[77]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

- ↑ Sweden and Slovenia were the reference states, with Ireland excluded as an outlier.[77]

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2013.[80]

- 1 2 Sweden, Latvia and Ireland were the reference states.[80]

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2014.[83]

- ↑ Latvia, Portugal and Ireland were the reference states, with Greece, Bulgaria and Cyprus excluded as outliers.[83]

- ↑ Latvia, Ireland and Portugal were the reference states.[83]

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2016.[86]

- ↑ Bulgaria, Slovenia and Spain were the reference states, with Cyprus and Romania excluded as outliers.[86]

- ↑ Slovenia, Spain and Bulgaria were the reference states.[86]

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2018.[89]

- ↑ Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[89]

- ↑ Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[89]

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2020.[92]

- ↑ Portugal, Cyprus, and Italy were the reference states.[92]

- ↑ Portugal, Cyprus, and Italy were the reference states.[92]

- ↑ Reference values from the Convergence Report of June 2022.[95]

- 1 2 France, Finland, and Greece were the reference states.[95]

See also

References

- ↑ "Euros in the wallets of the Slovaks, but who will be next?" (Press release). Sparkasse.at. 2008-08-05. Archived from the original on 2006-09-04. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ↑ Vláda přijala doporučení MF a ČNB zatím nestanovit cílové datum přijetí eura. (Czech) Ministry of Finance (Czech Republic). zavedenieura.cz.

- 1 2 Jaroslav Bukovský. Vstoupit do eurozóny? Až bude euro za dvacet korun, shodli se Babiš s Rusnokem. Published on 5 December 2017.

- 1 2 Přijetí eura se na čtyři roky odkládá. Podle vznikající vlády by to "nebylo výhodné". Published on 2 November 2021.

- ↑ Direct Democracy. sudd.ch

- ↑ "Topolánek a Tůma: euro v roce 2010 v ČR nebude". Novinky.cz (in Czech). 2006-09-19. Archived from the original on 2007-05-06. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ↑ "Euro je v Česku reálné v roce 2012, míní MF" [Adoption of euro in Czech Republic is realistic in 2012, says the Ministry of Finance]. Novinky.cz (in Czech). 2007-02-21. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ↑ "Topolánek: euro nepřijmeme asi ani v roce 2012" [Topolanek: we won't adopt Euro in 2012 either]. Novinky.cz (in Czech). 2007-11-18.

- ↑ "Euros in the wallets of the Slovaks, but who will be next?" (Press release). Sparkasse.at. 2008-08-05. Archived from the original on 2006-09-04. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ↑ "Czech euro adoption in 2014 or 2015 not realistic – Janota". FinancNoviny.cz. October 2009.

- ↑ "For Czechs, euro adoption still a long way off". Czech Radio. 2008-06-09.

- ↑ "Czech crown to stay long with no euro opt-out needed: PM". Reuters. 2010-12-05.

- ↑ Laca, Peter (2010-12-05). "Czech Republic Still Able to Opt Out of Adopting Euro, Prime Minister Says". Bloomberg.

- ↑ "Czechs, Poles cooler to euro as they watch debt crisis". Reuters. 16 June 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ↑ Pop, Valentina (28 October 2011). "Czech PM mulls euro referendum". EUObserver. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

"The conditions under which the Czech citizens decided in a referendum in 2003 on the country's accession to the EU and on its commitment to adopt the single currency, euro, have changed. That is why the ODS will demand that a possible accession to the single currency and the entry into the European stabilisation mechanism be decided on by Czech citizens," the ODS resolution says.

- ↑ "Czechs deeply divided on EU's fiscal union". Radio Praha. 19 January 2012.

- ↑ "ForMin: Euro referendum casts doubt on Czech pledges to EU". Prague Daily Monitor. 20 January 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- ↑ "Convergence Programme of the Czech Republic (April 2013)" (PDF). Ministry of Finance (Czech Republic). 26 April 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ "Česko nepřijme euro dříve než v roce 2019, předpokládá guvernér ČNB Singer (Czech not adopt the euro earlier than in 2019, assumed CNB Governor Singer)" (in Czech). Hospodářské Noviny iHNed. 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "CNB and MoF recommend not to set euro adoption date yet". Czech National Bank. 2013-12-18. Archived from the original on 2014-07-09. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ "Týden: Future to clear up diplomatic myths about new president". Prague Daily Monitor. 2013-02-12. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Bilefsky, Dan (2013-03-01). "Czechs Split Deeply Over Joining the Euro". The New York Times.

- ↑ "New Czech president will approve ESM". 2013-03-11. Archived from the original on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ↑ "Skeptical Czechs may be pushed to change tone on euro". Reuters. 26 April 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ Lopatka, Jan; Muller, Robert (2014-01-17). "Czech center-left leader becomes PM, seeking closer EU ties". Reuters. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ↑ "Zaorálek: Adopt euro ASAP". The Prague Post. 2014-01-30. Archived from the original on 2014-01-31. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- ↑ "TOP 09 starts election campaign". 2013-09-12. Archived from the original on 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

- ↑ "Incoming government more positive on euro-adoption". Radio Praha. 27 January 2014.

- ↑ "Convergence Programme of the Czech Republic (April 2014)" (PDF) (in Czech). Ministry of Finance (Czech Republic). 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "Czech president sees euro adoption by 2017". EU business. 11 June 2014.

- ↑ "Over 40,000 Czechs sign anti-euro petition". Radio Praha. 11 November 2014.

- ↑ "CNB and MoF recommend not to set euro adoption date yet". Czech National Bank. 15 December 2014. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ "Euro in five years, sick leave first three days, pensions. CSSD presented its priorities. (Euro za pět let, nemocenská první tři dny, důchody. ČSSD představila priority)" (in Czech). novinky.cz. 14 March 2015.

- ↑ "Czech government sets target of agreeing euro adoption process by 2020". IntelliNews. 28 April 2015.

- ↑ Czech Finance Minister Proposes Referendum on the Euro. The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "New Czech President Pavel to end international isolation". 30 January 2023.

- ↑ "Czech.cz". www.czech.cz. Archived from the original on 2021-07-11. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ↑ "September 2004 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "September 2005 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Zavedení eura v ČR" (Press release) (in Czech). Středisko empirických výzkumů. 2011-01-31. Archived from the original on 2014-12-29. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- ↑ "March April 2006 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "September 2006 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- 1 2 "September 2007 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "May 2008 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "May 2009 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "September 2009 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "2010 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "2011 May Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "2011 November Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "2012 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "2013 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "2014 Eurobarometer report" (PDF).

- ↑ "Občané o přijetí eura a dopadech vstupu ČR do EU – duben 2015 – Centrum pro výzkum veřejného mínění". cvvm.soc.cas.cz.

- ↑ "Economic and financial affairs website – Notice to users". European Commission – European Commission.

- ↑ "Občané ČR o budoucnosti EU a přijetí eura – duben 2016 – Centrum pro výzkum veřejného mínění". cvvm.soc.cas.cz.

- ↑ "Flash Eurobarometer 440 (April 2016) – reports". European Commission – European Commission.

- ↑ "Občané ČR o budoucnosti EU a přijetí eura – duben 2017 – Centrum pro výzkum veřejného mínění". cvvm.soc.cas.cz.

- ↑ 2017 Eurobarometer report overview, 2017 Eurobarometer report summary

- ↑ "Občané ČR o budoucnosti EU a přijetí eura – duben 2018 – Centrum pro výzkum veřejného mínění". cvvm.soc.cas.cz.

- ↑ "Flash Eurobarometer 465: Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the common currency". economy-finance.ec.europa.eu.

- ↑ "CVVM report 2019" (PDF).

- ↑ Flash Eurobarometer 465: Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the common currency. 7 June 2019.

- ↑ Flash Eurobarometer 487: Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the euro. June 2020.

- ↑ Flash Eurobarometer 492: Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the common currency. July 2021.

- ↑ Flash Eurobarometer 508: Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the common currency. 7 June 2019.

- ↑ "Introduction of the euro in the MS that have not yet adopted the common currency - Spring 2023". Eurobarometer. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

- ↑ Čadová, Naděžda; AVČR, Centrum pro výzkum veřejného mínění. "Členství České republiky v Evropské unii očima veřejnosti – duben/květen 2023". CVVM - Centrum pro výzkum veřejného mínění (in Czech). Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ↑ "Eurobarometer".

- ↑ "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "The corrective arm/ Excessive Deficit Procedure". European Commission. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ "Government deficit/surplus data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "General government gross debt (EDP concept), consolidated - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "ERM II – the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism". European Commission. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Convergence Report May 2012" (PDF). European Central Bank. May 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2012" (PDF). European Commission. March 2012. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2012" (PDF). European Commission. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2013" (PDF). European Commission. March 2013. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2013" (PDF). European Commission. February 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2014" (PDF). European Commission. April 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2014" (PDF). European Commission. March 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - June 2016" (PDF). European Commission. June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2016" (PDF). European Commission. May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Convergence Report 2018". European Central Bank. 2018-05-22. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - May 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Convergence Report 2020" (PDF). European Central Bank. 2020-06-01. Retrieved 2020-06-13.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - June 2020". European Commission. June 2020. Retrieved 2020-06-13.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2020". European Commission. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Convergence Report June 2022" (PDF). European Central Bank. 2022-06-01. Retrieved 2022-06-01.

- ↑ "Convergence Report 2022" (PDF). European Commission. 2022-06-01. Retrieved 2022-06-01.

- ↑ "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- 1 2 "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.