Daffy's Elixir (also sometimes known as Daffey's Elixir or Daffye's Elixir) is a name that has been used by several patent medicines over the years. It was originally designed for diseases of the stomach, but was later marketed as a universal cure. It remained a popular remedy in Britain and later the United States of America throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Origins

Daffy's Elixir was one of the most popular and frequently advertised patent medicines in Britain during the 18th century. It is reputed to have been invented by clergyman Thomas Daffy, rector of Redmile, Leicestershire, in 1647. He named it elixir salutis (lit. elixir of health) and promoted it as a generic cure-all.

Ingredients

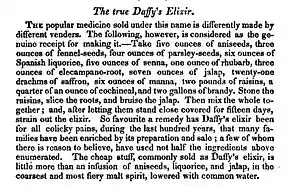

An early recipe for "True Daffy" from 1700 lists the following ingredients: aniseed, brandy, cochineal, elecampane, fennel seed, jalap, manna, parsley seed, raisin, rhubarb, saffron, senna and spanish liquorice. Chemical analysis has shown this to be a laxative made mostly from alcohol. Other recipes include Guiuacum wood chips, caraway, Salt of Tartar, and scammony.

Uses

According to an early nineteenth century advertisement it was used for the following ailments: The Stone in Babies and Children; Convulsion fits; Consumption and Bad Digestives; Agues; Piles; Surfeits; Fits of the Mother and Vapours from the Spleen; Green Sickness; Children's Distempers, whether the Worms, Rickets, Stones, Convulsions, Gripes, King's Evil, Joint Evil or any other disorder proceeding from Wind or Crudities; Gout and Rheumatism; Stone or Gravel in the Kidnies; Cholic and Griping of the Bowels; the Phthisic (both as cure and preventative provided always that the patient be moderate in drinking, have a care to prevent taking cold and keep a good diet; Dropsy and Scurvy.[1] The frequent use of the medicine to treat Colic, gripes or fret in horses was deplored in early veterinary manuals.[2]

Subsequent history

After Daffy's death in 1680 the recipe was left to his daughter Catherine, and his kinsmen Anthony and Daniel who were apothecaries in Nottingham. Anthony Daffy moved to London in the 1690s and began to exploit the product issuing pamphlets such as Directions for taking elixir salutis or, the famous purging cordial, known by the name of Daffy's elixir salutis [London], [1690?]. His widow Elleanor Daffy continued from about 1693 and (their daughter?) Katharine from about 1707. During the early 18th century the product was advertised widely in the emerging national and local newspapers. The success attracted several counterfeit copies, using inferior alcohol rather than brandy.

The medicine was later produced by William and Cluer Dicey & Co. of Bow Church yard c.1775 who claimed the sole rights of manufacture of the True Daffy's Elixir, although the recipe was not subject to any patent. Proprietorship was also then claimed by Peter Swinton of Salisbury Court and his son Anthony Daffy Swinton who may have been descended from the inventor.[3] Dicey and Co. and their successors marketed it in the United States of America.[4]

It then passed to Dicey and Sutton, and later to Messrs W. Sutton & Co. of Enfield in Middlesex, who continued to market it throughout the nineteenth century.

References in literature

The use of Daffy's elixir is referred to in Charles Dickens Oliver Twist 1838, Ch. II, where it is referred to as Daffy, in the sentence: 'Why, it's what I'm obliged to keep a little of in the house, to put into the blessed infants' Daffy, when they ain't well, Mr. Bumble, (the Parish Beadle)' replied Mrs. Mann as she opened a corner cupboard, and took down a bottle and glass. 'It's gin. I'll not deceive you, Mr. B. It's gin.'

It is also mentioned in the William Makepeace Thackeray book, Vanity Fair 1848, Chapter XXXVIII A Family In a Small Way, where it is referenced in the sentence ‘..and there found Mrs. Sedley in the act of surreptitiously administering Daffy’s Elixir to the infant.’

Daffy's elixir is mentioned in Anthony Trollope's novel Barchester Towers, 1857.[5]

Daffy's elixir is also mentioned on several occasions in Thomas Pynchon's novel Mason & Dixon, 1997, particularly by Jeremiah Dixon, who attempts to procure large quantities before beginning his surveying trip with Charles Mason. Dixon is warned by Benjamin Franklin, however, that imported Daffy's Elixir is extremely expensive, and he would be better off ordering a customized version from the apothecary. During the same visit, Dixon also orders laudanum, a well-known constipating agent.[6]

Early advertisements

Daffy’s original elixir salutis, vindicated against all counterfeits, &c. or, An advertisement by mee, Anthony Daffy, of London, citizen and student in physick, By way of vindication of my famous and generally approved cordial drink, (called elixir salutis) from the notoriously false suggestions of one Tho. Witherden of Bear-steed in the county of Kent, Gent. (as pretended;) Jane White, Robert Brooke, apothecary, and Edward Willet; all new upstatrt counterfitors of my elixir, and Ape-like imitators of my long since printed Books and Directions, (some of them, nigh verbatim, or word for word) and that to the jeopardy of many good, (but mis-in-formed) Peoples Healths, and Lives too; as also, from the false pretentions of other more sneaking Cub-Quacks, not yet lickt into form, but remaining Moon-blind brats, (still in swadling-clouts) I mean the numerous crew of libellous pamphleteeirs, which are (if possible) more dangerous counterfeiters of my Elixer . . . Advertisement by mee, Anthony Daffy s.n., 1690?].

Daffy’s original and famous elixir salutis: the choice drink of health: or, health-bringing drink. Being a famous cordial drink, found out by the providence of the Almighty, and (for above twenty years) experienced by himself, and divers persons (whose names are at most of their desires here inserted) a most excellent preservative of man-kind. A secret far beyond any medicament yet known, and is found so agreeable to nature, that it effects all its operations, as nature would have it, and as a virtual expedient proposed by her, for reducing all her extreams unto an equal temper; the same being fitted unto all ages, sexes, complexions, and constitutions, and highly fortifying nature against any noxious humour, invading or offending the noble parts. Never published by any but by Anthony Daffy, student in physick, and since continued by his widow Elleanor Daffy, London : printed with allowance, for the author, by Tho. Milbourn dwelling in Jewen-Street, 1693.

Thomas Daffy biography

Daffy (1671 – 1680), was educated at John Roysse's Free School in Abingdon, (now Abingdon School) from 1630 to circa 1634.[7] He gained a scholarship to Pembroke College, Oxford in 1634, (BA 1635, MA 1640).

He became rector of Harby in Leicestershire on the presentation of the Earl of Rutland before being removed (allegedly after causing offence to the Countess of Rutland). He took the incumbency of Vicar of Redmile in 1666, where he remained until his death.[8][9]

References

- ↑ Fleming, Lindsay (June 1953). "Daffy's Elixir". Notes and Queries. Oxford University Press: 238–9. doi:10.1093/nq/CXCVIII.jun.238.

- ↑ White, James (1820). Treatise on veterinary medicine. Vol. 2. London: Longman. p. 121.

- ↑ Fleming, (1953), p.238.

- ↑ Coxe, John Redman (1831). The American dispensatory. Philadelphia: Carey and Lea. p. 780.

- ↑ Trollope, Anthony (1977). Barchester Towers. London: Folio Society. p. 199.

- ↑ Pynchon, Thomas (1997). Mason & Dixon. New York: Penguin. p. 267.

- ↑ Richardson, William H (1905). List of Some Distinguished Persons Educated at Abingdon School 1563-1855. Hughes Market Place (Abingdon). p. 7.

- ↑ "Reverend Thomas Daffy Vicar of Redmile". Redmile Archive. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ↑ "Daffy, Thomas (1616/17–1680), inventor of the 'elixir salutis'". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7000. Retrieved 11 October 2023. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Bibliography

- A.C. Wootton, Chronicles of Pharmacy 1910, pp. 172–3.

- C.J.S. Thompson, Quacks of old London 1928, p. 225.

External links

- Reverend Thomas Daffy - Vicar of Redmile

- Nancy Cox and Karin Dannehl, Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1550-1820

- Homan, Peter G. (23 December 2006). "Daffy: a legend in his own preparation". The Pharmaceutical Journal.

- Osborne, Sally (20 August 2011). "The delights of Daffy". Eighteenth-century recipes(Blog).