Darius Nash Couch | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Darius Couch by Mathew Brady or Levin C. Handy taken in 1861 or 1862 | |

| Born | July 23, 1822 Putnam County, New York, US |

| Died | February 12, 1897 (aged 74) Norwalk, Connecticut, US |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1846–1855, 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | II Corps, Army of the Potomac Department of the Susquehanna 2nd Division, XXIII Corps |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War Seminole Wars American Civil War |

| Signature | |

Darius Nash Couch[1] (July 23, 1822 – February 12, 1897) was an American soldier, businessman, and naturalist. He served as a career U.S. Army officer during the Mexican–American War, the Second Seminole War, and as a general officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

During the Civil War, Couch fought notably in the Peninsula and Fredericksburg campaigns of 1862, and the Chancellorsville and Gettysburg campaigns of 1863. He rose to command a corps in the Army of the Potomac, and led divisions in both the Eastern Theater and Western Theater. Militia under his command played a strategic role during the Gettysburg Campaign in delaying the advance of Confederate troops of the Army of Northern Virginia and preventing their crossing the Susquehanna River, critical to Pennsylvania's defense.

He has been described as personally courageous, very thin in build, and (after his time in Mexico) frail of health.[2]

Early life and career

Couch[3] was born in 1822 on a farm in the village of Southeast in Putnam County, New York, and was educated at the local schools there.[4] In 1842 he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, graduating four years later 13th out of 59 cadets. On July 1, 1846, Couch was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant and was assigned to the 4th U.S. Artillery.[5]

Couch then saw action with the U.S. Army during the Mexican–American War, most notably in the Battle of Buena Vista on February 22–23, 1847. For his actions on the second day of this fight, he was brevetted a first lieutenant for "gallant and meritorious conduct." After the war ended in 1848 Couch began serving in garrison duty at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. The following year he was stationed at Fort Pickens, located near Pensacola, Florida, and then in Key West. Couch next participated in the Seminole Wars during 1849 and into 1850.[6]

Returning to garrison duty, later that year Couch was sent to Fort Columbus in New York Harbor, and in 1851 Couch was involved in recruiting at Jefferson Barracks located on the Mississippi River at Lemay, Missouri. Later in 1851 he returned to Fort Columbus, and then was ordered to Fort Johnston in Southport, North Carolina, staying there into 1852, and next in garrison at Fort Mifflin in Philadelphia until 1853.[6]

Couch then took a one-year leave of absence from the army from 1853 to 1854 to conduct a scientific mission for the Smithsonian Institution in northern Mexico. There, he discovered the species that are known as Couch's kingbird and Couch's spadefoot toad.[7] Upon his return to the United States in 1854, Couch was ordered to Washington, D.C., on detached service. Later that year he resumed garrison duty in Fort Independence at Castle Island along Boston Harbor, Massachusetts. Also in 1854 he was stationed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and would remain there into the following year. On April 30, 1855, Couch resigned his commission in the U.S. Army. From 1855 to 1857 he was a merchant in New York City.[6] He then moved to Taunton, Massachusetts, and worked as a copper fabricator in the company owned by his wife's family. Couch was still working in Taunton when the American Civil War began in 1861.[7]

American Civil War service

Early service

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Couch was appointed commander of the 7th Massachusetts Infantry on June 15, 1861, with the rank of colonel in the Union Army. That August he was promoted to brigadier general with an effective date back to May 17. He was given brigade command in the Military Division then Army of the Potomac that fall, and Couch was given divisional command in the VI Corps in the following spring.[8][5] From July 1861 to March 1862 he helped prepare and then maintain the defenses of Washington, D.C. He participated in the Peninsula Campaign, fighting in the Siege of Yorktown on April 5–May 4 and the Battle of Williamsburg the following day.[6]

Seven Pines

Couch led his division during the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31 and June 1, 1862. In this engagement his corps commander, Brig. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes, ordered Couch's division and that of Brig. Gen. Silas Casey forward of the Union defensive line, Couch's men right behind those of Casey. This placed the IV Corps in an isolated position, vulnerable to attack on three sides; however poorly coordinated Confederate movements allowed Couch and Casey to partially prepare entrenchments against the impending assault. As the fighting continued throughout May 31 both Couch and Casey were slowly driven back, with their right flank units in the most peril. At this time Couch counterattacked with his old 7th Massachusetts Infantry and the 62nd New York Infantry in an attempt to bolster that side, however he did not succeed and was forced back, as was the rest of the Union IV Corps by nightfall.[9]

Couch continued to lead his division during the 1862 Seven Days Battles that followed, fighting in the Battle of Oak Grove on June 25 and the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1. Later in July Couch's health began to fail, prompting him to offer his resignation. The army commander, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, refused to send it to the U.S. War Department, and instead Couch was promoted to major general, to date from July 4. Couch was involved in the Maryland Campaign that fall, although absent from the Battle of Antietam on September 17.[10][11]

Fredericksburg

On November 14, 1862, Couch was assigned command of the II Corps, and he led it during the Battle of Fredericksburg as part of Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner's "Right Grand Division".[5] In this fight Couch's corps contained three divisions, led by Brig. Gens. Winfield Scott Hancock, Oliver Otis Howard, and William H. French.[12] Early on December 12 infantry from his corps attempted to support the Union engineers' efforts to lay pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River and into the town. When Confederate fire repeatedly prevented this, and a heavy artillery bombardment failed as well, the decision was made to send small groups of soldiers across in pontoon boats to dislodge the defenders. This amphibious assault, which finally succeeded in driving out the Confederates, was executed by one of Couch's brigades under Col. Norman J. Hall (3rd Brigade, 2nd Division – 19th & 20th Massachusetts, 7th Michigan, 42nd & 59th New York, & 127th Pennsylvania).[13]

As the Union soldiers entered a smoldering Fredericksburg they began to sack the city, forcing Couch to order his provost guard to secure the bridges and collect the loot. The next day his corps was ordered to attack the Confederate position at the base of Marye's Heights above Fredericksburg. To better watch his men's progress Couch entered the town's courthouse and climbed its cupola, where he could see French's division advancing. As they approached the Confederate defenses, Couch could see his men taking very heavy fire and easily repulsed, described "as if the division had simply vanished." Hancock's division followed that of French, meeting the same fate with high casualties as well. Howard, who was to go in next, was with Couch as Hancock's division attacked. Briefly through the smoke they could see the mounting casualties, and Couch reportedly said, "Oh, great God! See how our men, our poor fellows, are falling."[14]

Couch ordered Howard to march his division toward the right and possibly flank the Confederate defenses his other two divisions had failed to dislodge. However the terrain did not permit any force that was marching from Fredericksburg toward Marye's Heights to attack anywhere other than at the stone wall along its base. When Howard's men attacked they were crowded back to the left, meeting the same resistance, and were repulsed. As other Union soldiers followed the II Corps in, Couch ordered his artillery to move into the field and blast the Confederates at close range. When his own artillery chief protested against exposing the gun crews in this fashion, Couch stated that he agreed but it was necessary to slow the Confederate fire in some way. The cannon stopped about 150 yards from the stone wall and opened fire, but quickly lost most of their crews and did little to slacken the enemy fire. During this time Couch moved slowly along his line of men, who were on the ground firing as best they could until nightfall.[15] Recounting the attack on the heights on December 13, Couch wrote after the war:

The musketry fire was very heavy & the artillery fire was simply terrible. I sent word, many times, to our artillery on the right of Falmouth that they were firing into us & tearing our own men to pieces. I thought they had made a mistake in the range. But I learned later that the fire came from the guns of the enemy on their extreme left.[16]

In the attack Couch's force suffered heavily, as did the rest of the Right Grand Division. He reported that the II Corps sustained over four thousand casualties during the Fredericksburg Campaign. French's division lost an estimated 1,200 soldiers and Hancock around 2,000. Howard lost about 850 men, 150 of which were hit on December 11 supporting the engineers at the river.[17] That night the Union wounded remained in the field, and Couch wrote after the war what he saw: "It was a night of dreadful suffering. Many died of wounds & exposure, and as fast as men died they stiffened in the wintry air, & on the front line were rolled forward for protection to the living. Frozen men were placed for dumb sentries."[16]

Chancellorsville

Following the Union defeat at Fredericksburg and the inglorious Mud March in January 1863, the commander of the Army of the Potomac—Couch's immediate superior—was again replaced. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside was relieved and Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker named to his place. Hooker reorganized the army and drew up plans for a new campaign against the Army of Northern Virginia. He wished to avoid attacking the Confederate defenses at Fredericksburg and sought to flank them out of position, thereby fighting on more open ground. After the reorganization Couch continued to lead the II Corps, with his divisions commanded by Hancock and French (both now major generals) and Brig. Gen. John Gibbon at the head of Howard's former division, a total of about 17,000 soldiers.[18]

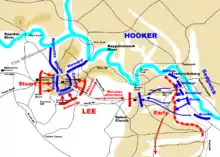

During the ensuing Chancellorsville Campaign Couch was the senior corps commander, making him Hooker's second-in-command. In late April, Hooker began moving his corps across the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers, ordering two of Couch's divisions to entrench and defend the Banks's Ford crossing of the Rappahannock and detach Gibbon's 5,000 men to remain at the Union camp back at Falmouth on April 29. The following day Couch had cleared the ford and was marching toward Chancellorsville. In the afternoon of May 1 Hooker—normally quite aggressive—cautiously slowed his marching army, and soon he stopped their movement altogether, despite some success against the Confederates and the loud protests of his corps commanders. Couch sent Hancock's division to bolster the Union men already engaged, and informed Hooker they could handle the enemy in front of them. However, Hooker's orders stood; march back into the positions they held the previous day and assume a defensive posture. Couch complied and ordered Hancock's division to form a rear guard as they withdrew. As Hancock formed his men, Couch could see Confederate artillery aiming for the massed Union columns, and he told his staff "Let us draw their fire." The group of mounted officers clustered around a clearing where the enemy cannon could easily view them, thus attracting their fire and sparing the marching infantry; Couch and his staff also went unharmed. By nightfall the Union soldiers were busy fortifying the ground. Couch formed his divisions behind the XII Corps in roughly the center of Hooker's line.[19][20]

By late afternoon on May 2, Hooker's line was hit on the right (the XI Corps led by Howard) by Confederates under Lt. Gen. Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson, and despite resisting the XI Corps was routed and ran toward Chancellorsville. The remaining corps tightened into a U-shaped formation by May 3, and Confederate artillery began shelling their positions, including Couch's men. At about 9 a.m. that day Hooker was stunned by enemy fire when a shell hit the pillar he was leaning on, temporarily incapacitating him within an hour. At that time Hooker turned command of the army over to Couch, and through consulting with a "groggy" Hooker it was decided to withdraw the army to defensive lines to the north, with the other commanders (except an embarrassed Howard) strongly advocating an attack instead.[21]

Gettysburg

Couch requested reassignment after quarreling with Hooker. President Abraham Lincoln offered him command of the Army of the Potomac, but he declined, citing poor health. He commanded the newly created Department of the Susquehanna during the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863.[22] Fort Couch in Lemoyne, Pennsylvania, was constructed under his direction and was named in his honor. Assigned to protect Harrisburg from a threatened attack by Confederates under Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, Couch directed militia from his department to skirmish with enemy cavalry elements at Sporting Hill, one of the war's northernmost engagements.[23] Couch's militia then joined the pursuit of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland after the Battle of Gettysburg.

Subsequent activities

Confederates again invaded Couch's Department of the Susquehanna in August 1864, as Brig. Gen. John McCausland burned the town of Chambersburg.[24] In December, Couch returned to the front lines with an assignment to the Western Theater, where he commanded a division in the XXIII Corps of the Army of the Ohio in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign and for the remainder of the war. Couch finished his military service after the Carolinas Campaign in 1865.

Postbellum career and death

Couch returned to civilian life in Taunton after the war, where he ran unsuccessfully as a Democratic candidate for Governor of Massachusetts in 1865. He later briefly served as president of a mining company in West Virginia. Couch moved to Connecticut in 1871, where he served as the Quartermaster General, and then Adjutant General, for the state militia until 1884. In 1888 he joined the Aztec Club of 1847 by right of his service in the Mexican War. He also joined the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution in 1890.

He died in Norwalk, Connecticut. He was buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Taunton.

Legacy

According to Herman Hattaway and Michael D. Smith:

Couch is best remembered as an able division and corps commander in the Army of the Potomac. His career occasionally was marred by personal traits of impatience and temper directed at both subordinates and superiors. He also suffered from prolonged bouts of ill health, which led to his acceptance of the post of department commander.[25]

In 2017, General Couch's portrait was featured on a mural in Lemoyne, Pennsylvania in commemoration of the defenses mounted in the town under his name during the Gettysburg campaign. The fort served as the last line of defense for Pennsylvania' capital city of Harrisburg.[26]

Couch is commemorated in the scientific names of two species of reptiles: Sceloporus couchii and Thamnophis couchii,[27] and one frog: Scaphiopus couchii.[28] He also has one bird species named for him: Couch's kingbird.

See also

Citations

- ↑ Couch's middle name was undoubtedly Nash, although a middle initial of "S" has appeared in reports and is listed that way in Dupuy, Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, p. 194.

- ↑ Gambone, Major-General Darius Nash Couch, p. 51.

- ↑ The correct pronunciation is /ˈkaʊtʃ/ "couch", not /ˈkoʊtʃ/ "coach", according to biographer Gambone, Major-General Darius Nash Couch, p. 1 footnote reads "According to family members, the proper pronunciation is Couch as in Ouch, not Cooch as is sometimes suggested.

- ↑ Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 Eicher, Civil War High Commands, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 4 "Aztec Club of 1847 site biography of Couch". aztecclub.com. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- 1 2 Heidler, Encyclopedia of the American Civil War, p. 505.

- ↑ Dupuy, Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, p. 194

- ↑ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 276–78.

- ↑ Aztec Club of 1847 site biography of Couch; Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 95

- ↑ Dupuy, Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, p. 194.

- ↑ Eicher, Longest Night, p, 396.

- ↑ Catton, Army of the Potomac: Glory Road, pp. 35–39.

- ↑ Catton, Army of the Potomac: Glory Road, pp. 42, 50, 53, 55–56.

- ↑ Catton, Army of the Potomac: Glory Road, pp. 56, 58–59.

- 1 2 Alexander, Fighting for the Confederacy, p. 179.

- ↑ "Couch's official reports for the Fredericksburg Campaign". aztecclub.com. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

- ↑ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 473–74, 475.

- ↑ Eicher, Longest Night, p. 475, 476, 478

- ↑ Catton, Army of the Potomac: Glory Road, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Fredriksen, Civil War Almanac, pp. 287–293; Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 485–486.

- ↑ Gambone, Major-General Darius Nash Couch, pp. 137–38.

- ↑ Gambone, Major-General Darius Nash Couch, p. 170.

- ↑ Gambone, Major-General Darius Nash Couch, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Herman Hattaway and Michael D. Smith, "Couch, Darius Nash" in American National Biography (2000) https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0400270

- ↑ "Fort Couch Historical Marker". ExplorePAHistory.com. 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Couch", p. 60).

- ↑ Dodd, C. Kenneth Jr. (2013-06-10). Frogs of the United States and Canada, 2-vol. set. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421410388.

General and cited references

- Alexander, Edward P. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander. Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989. ISBN 0-8078-4722-4.

- Catton, Bruce. Glory Road. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1952. ISBN 0-385-04167-5.

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson, and David L. Bongard. The Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 978-0-06-270015-5.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2, Fredericksburg to Meridian. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 0-394-49517-9.

- Fredriksen, John C. Civil War Almanac. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8160-7554-6.

- Gambone, A. M. Major General Darius Nash Couch: Enigmatic Valor. Baltimore: Butternut & Blue, 2000. ISBN 0-935523-75-8.

- Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler. "Darius Nash Couch." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

- Winkler, H. Donald. Civil War Goats and Scapegoats. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, 2008. ISBN 1-58182-631-1.

- The Union Army: A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, 1861–65—Records of the Regiments in the Union Army—Cyclopedia of Battles—Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers. Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing, 1997. First published 1908 by Federal Publishing Company. Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 of the 1908.

- Darius Nash Couch—Aztec Club of 1847 site biography of Couch.

- civilwarhome.com Couch's official reports for the Fredericksburg Campaign.

Further reading

- Bowen, James Lorenzo. Massachusetts in the War, 1861–1865. Springfield, MA: C. W. Bryan & Co., 1888. OCLC 1986476.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Darius Couch—Georgia's Blue and Gray Trail site biography; Archived 2010-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Couch's writings about the Chancellorville Campaign at historycentral.com

- Darius Nash Couch at the Wayback Machine (archived February 8, 2008) Photo gallery of Couch at www.generalsandbrevets.com