The state funeral procession of Emperor Shōwa | |

| Date |

|

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Budget | \10 billion |

| Participants | See list |

Hirohito (Emperor Shōwa), the 124th Emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, died on 7 January 1989 at Imperial Palace in Chiyoda, Tokyo, at the age of 87, after suffering from intestinal cancer for some time. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Akihito. The late emperor's state funeral was held on 24 February, when he was buried near his parents, Emperor Taishō and Empress Teimei, at the Musashi Imperial Graveyard in Hachiōji, Tokyo.

Illness and death

On 22 September 1987, the Emperor underwent surgery on his pancreas after having digestive problems for several months. The doctors discovered that he had duodenal cancer. The Emperor appeared to be making a full recovery for several months after the surgery. About a year later, however, on 19 September 1988, he collapsed in his palace, and his health worsened over the next several months as he suffered from continuous internal bleeding.

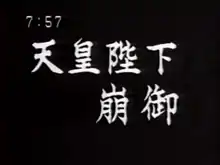

On 7 January 1989, at 7:55 am, the Grand Steward of Japan's Imperial Household Agency, Shōichi Fujimori, officially announced the death of Emperor Shōwa at 6:33 am, and revealed details about his cancer for the first time. He was survived by his wife, five children, ten grandchildren and one great-grandchild.[1]

Succession and posthumous title

Emperor Shōwa's death ended the Shōwa era. He was succeeded by his son, Crown Prince Akihito. With Emperor Akihito's accession, a new era began: the Heisei era, effective at midnight the day after Emperor Shōwa's death. The new Emperor's formal enthronement ceremony was held in Tokyo on 12 November 1990.

From 7 January until 31 January 1989, the late Emperor's formal appellation was Taikō Tennō (大行天皇, "Departed Emperor"). The late Emperor's definitive posthumous name, Shōwa Tennō (昭和天皇), was officially determined on 13 January and formally released on 31 January by Noboru Takeshita, the Prime Minister.

State funeral

On Friday, 24 February Emperor Shōwa's state funeral was held, and unlike that of his predecessor, although formal it was not conducted in a strictly Shinto manner.[2] It was a funeral carefully designed both as a tribute to the late Emperor and as a showcase for the peaceful, affluent society into which Japan had developed during his reign.[3]

Unlike Emperor Taishō's funeral 62 years earlier, there was no ceremonious parade of officials dressed in military uniforms, and there were far fewer of the Shinto rituals used at that time to glorify the Emperor as a near-deity. These changes were meant to highlight that the Emperor Shōwa's funeral would be the first of an emperor under the postwar democratic Constitution, and the first imperial funeral held in daylight.[3]

The delay of 48 days between his death and the funeral was about the same as that for the previous Emperor, and allowed time for numerous ceremonies leading up to the funeral.[3] The late Emperor's body lay in three coffins; some personal items such as books and stationery were also placed into them.

Ceremony at the Imperial Palace

The ceremonies began at 7:30 a.m. when Emperor Akihito conducted a private Ceremony of Farewell for his father in the Imperial Palace.[2]

Funeral procession through Tokyo

At 9:35 a.m., a black motor hearse carrying the body of Emperor Shōwa left the Imperial Palace for the two-mile-long drive to the Shinjuku Gyoen Garden, where the Shinto and state ceremonies were held.[2] The hearse was accompanied by traditional music played on the shō, a Japanese free reed aerophane; the crowd was largely silent as the hearse bearing the Emperor's coffin drove over a stone bridge and out through the Imperial Palace gates. A brass band played a dirge composed for the funeral of Emperor Shōwa's great-grandmother in the late 19th century, and cannon shots were fired in accompaniment.[3]

The motor hearse was accompanied by a procession of 60 cars. The route of the cortege through Tokyo was lined by an estimated 800,000 spectators and 32,000 special police, who had been mobilized to guard against potential terrorist attacks.[2]

The path of the funeral procession passed the National Diet, the democratic core of modern Japan, and the National Stadium, where the emperor opened the 1964 Summer Olympics and heralded Japan's postwar re-emergence.[2]

Ceremonies at Shinjuku Gyoen Garden

The 40-minute procession, accompanied by a brass band, ended when it pulled into the Shinjuku Gyoen Garden, until 1949 reserved for the use of the Imperial family and now one of Tokyo's most popular parks.[3]

At the Shinjuku Gyoen Garden, the funeral ceremonies for Emperor Shōwa were conducted in a Sojoden, a specially constructed funeral hall. The funeral hall was constructed of Japanese cypress and held together with bamboo nails, in keeping with ancient imperial tradition.[2]

The official guests were seated in two white tents located in front of the funeral hall. Because of the low temperatures, many guests used chemical hand-warmers and wool blankets to keep warm as the three-hour Shinto and state ceremonies progressed.[2]

Palanquin procession

Emperor Shōwa's coffin was transferred into a palanquin made of cypress wood painted with black lacquer. Attendants wearing sokutai and bearing white and yellow banners, shields and signs of the sun and moon, led a 225-member procession as musicians played traditional court music (gagaku). Next came gray-robed attendants carrying two sacred sakaki trees draped with cloth streamers and ceremonial boxes of food and silk cloths to be offered to the spirit of the late Emperor.[3]

In a nine-minute procession, 51 members of the Imperial Household Agency, clad in traditional gray Shinto clothing, carried the 1.5 ton Sokaren (Imperial Palanquin) containing the three-layered coffin of the Emperor Shōwa into the funeral hall, as they walked up the aisle between the white tents with domestic and foreign dignitaries.[2][3]

Behind the coffin walked a chamberlain dressed in white, who carried a platter with a pair of white shoes, as it is traditionally held that the deceased Emperor would wear them to heaven.[2] The new Emperor, Akihito, and the Empress Michiko, carrying their own large umbrellas, followed the palanquin with other family members.[3]

The procession passed through a small wooden torii gate, the Shinto symbol marking the entrance to sacred space, and filed into the Sojoden.[3]

Shinto ceremony

The events in the Sojoden were divided into a religious Sojoden no Gi ceremony, followed by the state Taiso no Rei ceremony.[2]

When the procession entered the funeral hall, the Shinto portion of the funeral began and a black curtain partition was drawn closed. It opened to reveal a centuries-old ceremony. To the accompaniment of chanting, officials approached the altar of the Emperor, holding aloft wooden trays of sea bream, wild birds, kelp, seaweed, mountain potatoes, melons and other delicacies. The foods, as well as silk cloths, were offered to the spirit of the late Emperor.

The chief of ceremony, a childhood classmate and attendant of Emperor Shōwa, then delivered an address, followed by Emperor Akihito.[3]

The funeral continued as the black curtain closed, signalling the end of the Shinto portion of the funeral.[3]

State ceremony

As the curtain parted again, Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary opened the state portion of the funeral. At noon, he called for a minute of silence throughout Japan.[3] Prime Minister Takeshita delivered a short eulogy, in which he said that the reign of the late emperor would be remembered for its eventful and tumultuous times, including the Second World War and the eventual reconstruction of Japan.[2] Foreign dignitaries approached the altar one at a time to pay their respects.[3]

Ceremony at the Imperial Graveyard

Following the state ceremony, the Emperor Shōwa's coffin was taken to the Musashi Imperial Graveyard in the Hachiōji district of Tokyo for burial. At Emperor Taishō's funeral in 1927, the trip to the Musashi Imperial Graveyard was carried out as a 3-hour procession, but at the Emperor Shōwa's funeral, the trip was made by motor hearse and cut to 40 minutes.[2] Several hours of ceremonies followed there, until the late emperor was laid to rest at nightfall, the traditional time to bury emperors.[3]

Visitors and guests

Summary

An estimated 200,000 people lined the site of the procession – far fewer than the 860,000 that officials had projected.[3] The Emperor Shōwa's funeral was attended by some 10,000 official guests. A total of 163 countries (out of 166 at that time) and 27 international organizations sent representatives to the event. More than 70 world leaders attended the funeral of the Emperor.

In total, there were 53 heads of state, 15 heads of government, 19 deputy heads of state, 17 members of royal families, 43 foreign ministers and other officials present, all of which required placing Tokyo under an unprecedented blanket of security. Because of security concerns for the dignitaries and because of threats from Japanese left-wing extremists to disrupt the funeral, authorities decided to scrap many of the traditional events that normally accompany funerals for Japanese monarchs. Officials also overrode protocol to give US President George H. W. Bush a front-row seat, even though tradition would have put him toward the back, at the fifty fifth seat,[4] because of his short time in office. Bush, who arrived in Tokyo on Thursday afternoon, attended the funeral on Friday afternoon and departed for China on Saturday.[2]

Japanese officials said it was the biggest funeral in modern Japanese history, and the unprecedented turnout of world leaders was recognition of Japan's emergence as an economic superpower. The Emperor Shōwa was the longest-reigning emperor in Japanese history and the last of the major leaders from World War II. Many also viewed the burial of the emperor as the nation's final break with a militaristic past that plunged much of Asia into war in the 1930s.[2] The late emperor's wife, the Empress Dowager Nagako, did not attend the ceremonies due to a lingering back and leg malady.[2]

The event hold records for the largest gathering of international leaders in world history at that time for a state funeral, surpassed the funeral of Josip Broz Tito in 1980. It would stand for the next 16 years until Pope John Paul II's funeral in 2005.

Japanese Imperial Family

- The Emperor and Empress, the late Emperor's son and daughter-in-law

- The Prince Hiro, the late Emperor's grandson

- The Prince Aya, the late Emperor's grandson

- The Princess Nori, the late Emperor's granddaughter

- The Former Princess Yori and Takamasa Ikeda, the late Emperor's daughter and son-in-law

- The Prince and Princess Hitachi, the late Emperor's son and daughter-in-law

- The Former Princess Suga and Hisanaga Shimazu, the late Emperor's daughter and son-in-law

- The Princess Takamatsu, the late Emperor's sister-in-law

- The Prince and Princess Mikasa, the late Emperor's brother and sister-in-law

- Former Princess Yasuko of Mikasa and Tadateru Konoe, the late Emperor's niece and nephew-in-law

- Prince and Princess Tomohito of Mikasa, the late Emperor's nephew and niece-in-law

- Former Princess Masako of Mikasa and Masayuki Sen, the late Emperor's niece and nephew-in-law

- The Prince and Princess Takamado, the late Emperor's nephew and niece-in-law

Absentees

- The Empress Dowager, the late Emperor's widow

- The Former Princess Taka, the late Emperor's daughter

- The Princess Chichibu, the late Emperor's sister-in-law

- The Prince Katsura, the late Emperor's nephew

Foreign dignitaries

The foreign dignitaries who attended the funeral:[5][6]

Members of royal houses

Sheikh Ali bin Khalifa Al Khalifa (representing the Emir of Bahrain)

Sheikh Ali bin Khalifa Al Khalifa (representing the Emir of Bahrain).svg.png.webp) The King of the Belgians

The King of the Belgians The King of Bhutan

The King of Bhutan The Sultan of Brunei

The Sultan of Brunei Prince Henrik of Denmark (representing the Queen of Denmark)

Prince Henrik of Denmark (representing the Queen of Denmark) The King of Jordan

The King of Jordan Tuanku Muhriz, prince of the Negeri Sembilan royal family

Tuanku Muhriz, prince of the Negeri Sembilan royal family.svg.png.webp) The King of Lesotho

The King of Lesotho The Crown Prince of Morocco (representing the King of Morocco)

The Crown Prince of Morocco (representing the King of Morocco) The Queen of the Netherlands

The Queen of the Netherlands The Crown Prince of Norway (representing the King of Norway)

The Crown Prince of Norway (representing the King of Norway).svg.png.webp) The Sultan of Oman

The Sultan of Oman The King and Queen of Spain

The King and Queen of Spain The King and Queen of Sweden

The King and Queen of Sweden The Crown Prince of Thailand (representing the King of Thailand)

The Crown Prince of Thailand (representing the King of Thailand) The King and Queen of Tonga

The King and Queen of Tonga The Duke of Edinburgh (representing the Queen of the United Kingdom)

The Duke of Edinburgh (representing the Queen of the United Kingdom)

Head of State

O le Ao o Samoa, His Highness Susuga Malietoa Tanumafili II

O le Ao o Samoa, His Highness Susuga Malietoa Tanumafili II President of Argentina Raul Alfonsin

President of Argentina Raul Alfonsin President of Bangladesh Hussain Muhammad Ershad

President of Bangladesh Hussain Muhammad Ershad.svg.png.webp) President of Brazil Jose Sarney

President of Brazil Jose Sarney President Pierre Buyoya

President Pierre Buyoya.svg.png.webp) President of Comoros Salim Ben Ali

President of Comoros Salim Ben Ali.svg.png.webp) President of Cyprus George Vassiliou

President of Cyprus George Vassiliou President of Egypt Hosni Mubarak

President of Egypt Hosni Mubarak President of Fiji Penaia Ganilau

President of Fiji Penaia Ganilau President of Finland Mauno Koivisto

President of Finland Mauno Koivisto President of France François Mitterrand

President of France François Mitterrand President of Ghana Jerry Rawlings

President of Ghana Jerry Rawlings President of Greece Christos Sartzetakis

President of Greece Christos Sartzetakis President of the Council of State Joao Bernardo Vieira

President of the Council of State Joao Bernardo Vieira President of Honduras José Azcona del Hoyo

President of Honduras José Azcona del Hoyo President of Hungary Brunó Ferenc Straub

President of Hungary Brunó Ferenc Straub President of Iceland Vigdis Finnbogadottir

President of Iceland Vigdis Finnbogadottir President of India Ramaswamy Venkataraman

President of India Ramaswamy Venkataraman President of Indonesia Suharto

President of Indonesia Suharto President of Ireland Patrick J. Hillery

President of Ireland Patrick J. Hillery President of Israel Chaim Herzog

President of Israel Chaim Herzog President of Italy Francesco Cossiga

President of Italy Francesco Cossiga President of Kenya Daniel arap Moi

President of Kenya Daniel arap Moi President of Maldives Maumoon Abdul Gayoom

President of Maldives Maumoon Abdul Gayoom.svg.png.webp) President of Mongolia Jambyn Batmönkh

President of Mongolia Jambyn Batmönkh President of Nigeria Ibrahim Babangida

President of Nigeria Ibrahim Babangida President of Palestine Yasser Arafat

President of Palestine Yasser Arafat.svg.png.webp) President of the Philippines Corazon Aquino

President of the Philippines Corazon Aquino President of Portugal Mário Soares

President of Portugal Mário Soares President of Sri Lanka Ranasinghe Premadasa

President of Sri Lanka Ranasinghe Premadasa President of Syria Hafez al-Assad

President of Syria Hafez al-Assad President of Togo Gnassingbe Eyadema

President of Togo Gnassingbe Eyadema President of Uganda Yoweri Museveni

President of Uganda Yoweri Museveni President of the United States George H. W. Bush

President of the United States George H. W. Bush President of Vanuatu Fred Timakata

President of Vanuatu Fred Timakata President of West Germany Richard von Weizsäcker

President of West Germany Richard von Weizsäcker.svg.png.webp) President of Zaire Mobutu Sese Seko[7]

President of Zaire Mobutu Sese Seko[7].svg.png.webp) President of Zambia Kenneth Kaunda

President of Zambia Kenneth Kaunda President of Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe

President of Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe

Prime Minister/Vice-President

.svg.png.webp) Prime Minister Wilfried Martens

Prime Minister Wilfried Martens Vice-President of Council of Ministers and Minister of Education José Ramón

Vice-President of Council of Ministers and Minister of Education José Ramón Prime Minister of Djibouti Barkat Gourad Hamadou

Prime Minister of Djibouti Barkat Gourad Hamadou Vice-President Carlos Morales Troncoso

Vice-President Carlos Morales Troncoso Prime Minister Fikre-Selassie Wogderess

Prime Minister Fikre-Selassie Wogderess First Vice-President and Prime Minister Hamilton Green

First Vice-President and Prime Minister Hamilton Green Vice President of Iran Mostafa Mir-Salim

Vice President of Iran Mostafa Mir-Salim.svg.png.webp) Vice President of Iraq Taha Muhie-eldin Marouf

Vice President of Iraq Taha Muhie-eldin Marouf Vice-President Teatao Teannaki

Vice-President Teatao Teannaki Vice President of Laos Phoun Sipaseut

Vice President of Laos Phoun Sipaseut Vice-President Harry F. Moniba

Vice-President Harry F. Moniba Prime Minister Mamane Oumarou

Prime Minister Mamane Oumarou Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto

Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto Vice President of Poland Kazimierz Barcikowski

Vice President of Poland Kazimierz Barcikowski Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew

Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew.svg.png.webp) Prime Minister of South Korea Kang Young Hoon

Prime Minister of South Korea Kang Young Hoon Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez

Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez Prime Minister Sotsha E. Dlamini

Prime Minister Sotsha E. Dlamini Prime Minister Carl Bildt

Prime Minister Carl Bildt Prime Minister and First Vice President Joseph Sinde Warioba

Prime Minister and First Vice President Joseph Sinde Warioba Prime Minister of Tunisia Hedi Baccouche

Prime Minister of Tunisia Hedi Baccouche Prime Minister of Turkey Turgut Özal

Prime Minister of Turkey Turgut Özal Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.svg.png.webp) Vice President of the Presidency of Yugoslavia Stane Dolanc

Vice President of the Presidency of Yugoslavia Stane Dolanc

Minister/International Represents of Foreign Affairs

Minister of External Relations Pedro de Castro Van Dunen

Minister of External Relations Pedro de Castro Van Dunen.svg.png.webp) Minister of External Relations Leo Tindemans

Minister of External Relations Leo Tindemans.svg.png.webp) Deputy Vice-Minister of Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mary Carrasco Monje

Deputy Vice-Minister of Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mary Carrasco Monje Minister of External Affairs Gaositwe K.T. Chiepe

Minister of External Affairs Gaositwe K.T. Chiepe.svg.png.webp) Minister of External Relations Roberto de Abreu Sodre

Minister of External Relations Roberto de Abreu Sodre Minister of External Relations Jean Marc Palm

Minister of External Relations Jean Marc Palm Minister of Foreign Affairs Silvino Manuel Da Luz

Minister of Foreign Affairs Silvino Manuel Da Luz Minister of Foreign Affairs Michel Gbezera-Bria

Minister of Foreign Affairs Michel Gbezera-Bria Minister of Foreign Affairs Hernan Felipe Errazuriz

Minister of Foreign Affairs Hernan Felipe Errazuriz Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China Qian Qichen

Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China Qian Qichen Deputy Minister for Foreign Relations Esther Lozano de Ray

Deputy Minister for Foreign Relations Esther Lozano de Ray.svg.png.webp) Minister of Foreign Affairs, Cooperation and Trade Said Kafe

Minister of Foreign Affairs, Cooperation and Trade Said Kafe Minister of Foreign Affairs and Worship Rodrigo Madrigal Nieto

Minister of Foreign Affairs and Worship Rodrigo Madrigal Nieto Minister of Foreign Affairs Ricardo Acevedo Peralta

Minister of Foreign Affairs Ricardo Acevedo Peralta Minister of Foreign Affairs Roland Dumas

Minister of Foreign Affairs Roland Dumas Minister of External Affairs Alhaji Omar B. Sey

Minister of External Affairs Alhaji Omar B. Sey Minister of Foreign Affairs The Chief of Battalion Jean Traore

Minister of Foreign Affairs The Chief of Battalion Jean Traore Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Gabor Nagy

Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Gabor Nagy Minister of External Affairs P.V. Narasimha Rao

Minister of External Affairs P.V. Narasimha Rao.svg.png.webp) Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Wisam Al-Zahawi

Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Wisam Al-Zahawi Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Gilberto Bonalumi

Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Gilberto Bonalumi Vice-Chairman of the Council of Ministers and Minister of Foreign Affairs Phoune Sipaseuth

Vice-Chairman of the Council of Ministers and Minister of Foreign Affairs Phoune Sipaseuth Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Soubanh Srithirath

Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Soubanh Srithirath Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Robert Goebbels

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Robert Goebbels Minister of Foreign Affairs Jean Bemananjara

Minister of Foreign Affairs Jean Bemananjara Minister of Foreign Affairs Dato' Abu Hassan bin Haji Omar

Minister of Foreign Affairs Dato' Abu Hassan bin Haji Omar Minister of Foreign Affairs Fathulla Jameel

Minister of Foreign Affairs Fathulla Jameel Private Secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Adrian Camilleri

Private Secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Adrian Camilleri Minister of Foreign Affairs Torn Kijiner

Minister of Foreign Affairs Torn Kijiner.svg.png.webp) Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Mohamed Sidina Ould Sidiya

Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Mohamed Sidina Ould Sidiya Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Abdellatif Filali

Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Abdellatif Filali Minister of External Affairs Ike Nwachukwu

Minister of External Affairs Ike Nwachukwu Minister of Foreign Affairs Thorvald Stoltenberg

Minister of Foreign Affairs Thorvald Stoltenberg Minister of Foreign Affairs Jorge Eduardo Ritter

Minister of Foreign Affairs Jorge Eduardo Ritter Minister of External Affairs Luis Maria Argana

Minister of External Affairs Luis Maria Argana Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Antoine Ndinga-Oba

Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Antoine Ndinga-Oba.svg.png.webp) Deputy Director of the Fourth Direction of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ioan Gorita

Deputy Director of the Fourth Direction of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ioan Gorita Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Abdulrahman Mansouri

Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Abdulrahman Mansouri Minister of Foreign Affairs Ibrahima Fall

Minister of Foreign Affairs Ibrahima Fall Minister of Foreign Affairs Abdul Karim Koroma

Minister of Foreign Affairs Abdul Karim Koroma Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Rogachev Igorj Alekseevich

Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Rogachev Igorj Alekseevich Secretary of State James A. Baker III

Secretary of State James A. Baker III Minister of Foreign Affairs Enrique Tejera Paris

Minister of Foreign Affairs Enrique Tejera Paris

Ambassador

Ambassador Justin Papajorgji

Ambassador Justin Papajorgji Ambassador Noureddine Yazid Zerhouni

Ambassador Noureddine Yazid Zerhouni Ambassadress and Director of Asia and Oceania Department, Ministry of External Relations Maria de Jesus Haller

Ambassadress and Director of Asia and Oceania Department, Ministry of External Relations Maria de Jesus Haller Ambassador Hedayetul Huq

Ambassador Hedayetul Huq.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Patrick Nothomb

Ambassador Patrick Nothomb Ambassador Atlay Digby Morales

Ambassador Atlay Digby Morales Ambassador Dasho Karma Letho

Ambassador Dasho Karma Letho.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Arnold Hofman-Bang Soleto

Ambassador Arnold Hofman-Bang Soleto.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Carlos Antonio Bettencourt Bueno

Ambassador Carlos Antonio Bettencourt Bueno Ambassador Pengiran Dato Paduka Haji Idriss

Ambassador Pengiran Dato Paduka Haji Idriss wife of Ambassador Peter Bashikarov

wife of Ambassador Peter Bashikarov Ambassador Hama Arba Diallo

Ambassador Hama Arba Diallo.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Ba Thwin

Ambassador Ba Thwin Ambassador Etienne Ntsama

Ambassador Etienne Ntsama.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Barry Connell Steers

Ambassador Barry Connell Steers Ambassador Issa Abbas Ali

Ambassador Issa Abbas Ali Ambassador Gustavo Ponce Lerou

Ambassador Gustavo Ponce Lerou Ambassador Yang Zhenya

Ambassador Yang Zhenya Ambassador Fidel Duque Ramirez

Ambassador Fidel Duque Ramirez Ambassador Amadeo Blanco Valdes-Fauly

Ambassador Amadeo Blanco Valdes-Fauly Ambassador Rudolf Jakubik

Ambassador Rudolf Jakubik Ambassador William Thune Andersen

Ambassador William Thune Andersen Ambassador Rachad Ahmed Saleh Farah

Ambassador Rachad Ahmed Saleh Farah Ambassador Alfonso Canto Dinzey

Ambassador Alfonso Canto Dinzey Ambassador Manfred Schmidt

Ambassador Manfred Schmidt Ambassador Marcelo Avila Orejuela

Ambassador Marcelo Avila Orejuela Ambassador Wahib Fahmy El-Miniawy

Ambassador Wahib Fahmy El-Miniawy Ambassador Ernesto Arrieta Peralta

Ambassador Ernesto Arrieta Peralta Ambassador Worku Moges

Ambassador Worku Moges Ambassador Charles Walker

Ambassador Charles Walker Ambassador Pauli S. Opas

Ambassador Pauli S. Opas Ambassador Bernard Dorin

Ambassador Bernard Dorin Ambassador James Leslie Mayne Amissah

Ambassador James Leslie Mayne Amissah Ambassador George Lianis

Ambassador George Lianis Ambassador El Hadj Boubacar Barry

Ambassador El Hadj Boubacar Barry Ambassador Anibal Enrique Quinomez Abarca

Ambassador Anibal Enrique Quinomez Abarca Ambassador Andras Forgacs

Ambassador Andras Forgacs Ambassador Arjun Gobindram Asrani

Ambassador Arjun Gobindram Asrani Ambassador Seyed Mohammad Hossein Adeli

Ambassador Seyed Mohammad Hossein Adeli.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Rashid M.S. Al-Rifai

Ambassador Rashid M.S. Al-Rifai Ambassador Sean G. Ronan

Ambassador Sean G. Ronan Ambassador Nahum Eshkol

Ambassador Nahum Eshkol Ambassador Bartolomeo Attolico

Ambassador Bartolomeo Attolico Ambassador Pierre Nelson Coffi

Ambassador Pierre Nelson Coffi Ambassador Khaled Madadha

Ambassador Khaled Madadha Ambassador Abdul-Aziz Abdullatif Al-Sharekh

Ambassador Abdul-Aziz Abdullatif Al-Sharekh Ambassador Souphanthaheuangsi Sisaleumsak

Ambassador Souphanthaheuangsi Sisaleumsak Ambassador Amir El-Khoury

Ambassador Amir El-Khoury.svg.png.webp) Ambassador T.B. Moeketsi

Ambassador T.B. Moeketsi Ambassador Stephen J. Koffa

Ambassador Stephen J. Koffa Ambassador Jean-Louis Wolzfeld

Ambassador Jean-Louis Wolzfeld Ambassador Hubert Maxime Rajaobelina

Ambassador Hubert Maxime Rajaobelina Ambassador Dato' J.A. Kamil

Ambassador Dato' J.A. Kamil Ambassador Abdoulaye Amadou Sy

Ambassador Abdoulaye Amadou Sy Ambassador J. Gauci

Ambassador J. Gauci.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Taki Ould Sidi

Ambassador Taki Ould Sidi.svg.png.webp) Ambassador-Director of the Asia and Middle East Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Moctar Ould Haye

Ambassador-Director of the Asia and Middle East Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Moctar Ould Haye.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Buyantyn. Dashtseren

Ambassador Buyantyn. Dashtseren Ambassador Abdelaziz Benjelloun

Ambassador Abdelaziz Benjelloun Ambassador Lopes Tembe Ndelana

Ambassador Lopes Tembe Ndelana Ambassador Narayan Prasad Arjal

Ambassador Narayan Prasad Arjal Ambassador Herman Ch. Posthumus Meyjes

Ambassador Herman Ch. Posthumus Meyjes Ambassador Rodney James Gates

Ambassador Rodney James Gates Ambassador Jorge Huezo Castrillo

Ambassador Jorge Huezo Castrillo Ambassador Mai-Bukar Garba Dogon-Yaro

Ambassador Mai-Bukar Garba Dogon-Yaro Ambassador Hakon W. Freihow

Ambassador Hakon W. Freihow.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Dawood bin Hamdan bin Abdulla Al-Hamdan,

Ambassador Dawood bin Hamdan bin Abdulla Al-Hamdan, Ambassador Mansur Ahmad

Ambassador Mansur Ahmad Ambassador Alberto A. Calvo Ponce

Ambassador Alberto A. Calvo Ponce Ambassador Joseph Kaal Nombri

Ambassador Joseph Kaal Nombri Ambassador Juan Carlos Hrase Von Bargen

Ambassador Juan Carlos Hrase Von Bargen Ambassador Luis J. Macchiavello Amoros

Ambassador Luis J. Macchiavello Amoros.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Ramon V. del Rosario

Ambassador Ramon V. del Rosario Ambassador Ryszard Frackiewicz

Ambassador Ryszard Frackiewicz Ambassador Jose Eduardo Mello Gouveia

Ambassador Jose Eduardo Mello Gouveia Ambassador Mohammed Ali Al-Ansari

Ambassador Mohammed Ali Al-Ansari.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Constantin Vlad

Ambassador Constantin Vlad.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Joseph Nizeyimana

Ambassador Joseph Nizeyimana Ambassador Manlio Cadelo

Ambassador Manlio Cadelo Ambassador Fawzi Bin Abdul Majeed Shobokshi

Ambassador Fawzi Bin Abdul Majeed Shobokshi Ambassador Keba Birane Cisse

Ambassador Keba Birane Cisse Ambassador Sheku Badara Basiru Dumbuya

Ambassador Sheku Badara Basiru Dumbuya Ambassador Cheng Tong Fatt

Ambassador Cheng Tong Fatt Ambassador Hassan Abshir Farah

Ambassador Hassan Abshir Farah.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Lee Won-Kyung

Ambassador Lee Won-Kyung Ambassador Solovjev Nikolai Nikolaevich

Ambassador Solovjev Nikolai Nikolaevich Ambassador Camilo Barcia Garcia-Villamil

Ambassador Camilo Barcia Garcia-Villamil Ambassador Karunasena Kodituwakku

Ambassador Karunasena Kodituwakku Ambassador Mohammed Abdel Dayim Basheer

Ambassador Mohammed Abdel Dayim Basheer Ambassador to the Netherlands Cyrill Ramkisoor

Ambassador to the Netherlands Cyrill Ramkisoor Ambassador Ove F. Heyman

Ambassador Ove F. Heyman.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Roger Bar

Ambassador Roger Bar Ambassador Ali Said Mchumo

Ambassador Ali Said Mchumo Ambassador Birabhongse Kasemsri

Ambassador Birabhongse Kasemsri Ambassador Yao Bloua Agbo

Ambassador Yao Bloua Agbo Ambassador to India Premchand J. Dass

Ambassador to India Premchand J. Dass Ambassador Abdelhamid Ben Messaouda, Ambassador

Ambassador Abdelhamid Ben Messaouda, Ambassador Ambassador Umut Arık

Ambassador Umut Arık Ambassador William Wycliffe Rwetsiba

Ambassador William Wycliffe Rwetsiba Ambassador Hamad Salem Al-Maqami

Ambassador Hamad Salem Al-Maqami Ambassador John Whitehead and Lady Whitehead

Ambassador John Whitehead and Lady Whitehead Ambassador Alfredo Giro Pintos

Ambassador Alfredo Giro Pintos Ambassador Fernando Baez-Duarte

Ambassador Fernando Baez-Duarte Ambassador Vo Van Sung

Ambassador Vo Van Sung Ambassador Hans-Joachim Hallier

Ambassador Hans-Joachim Hallier Ambassador Mohamed Abdul Koddos Alwazir

Ambassador Mohamed Abdul Koddos Alwazir.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Tarik Ajanovic

Ambassador Tarik Ajanovic.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Murairi Mitima Kaneno

Ambassador Murairi Mitima Kaneno.svg.png.webp) Ambassador Boniface Salimu Zulu

Ambassador Boniface Salimu Zulu

Representatives

Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Personal Representative of the President Bukarii Mahamadu Gabriel

Personal Representative of the President Bukarii Mahamadu Gabriel.svg.png.webp) Personal Representative Prince Norodom Ranariddh

Personal Representative Prince Norodom Ranariddh Vice-President of Council of Ministers and Minister of Education José Ramón

Vice-President of Council of Ministers and Minister of Education José Ramón Represented by the Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Represented by the Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Personal Representative of the President Ali Ben Bongo

Personal Representative of the President Ali Ben Bongo Represented by the Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Represented by the Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.svg.png.webp) Personal Representative of H.M. the Sultan Sayyid Thuwaini bin Shihab Al-Busaidi

Personal Representative of H.M. the Sultan Sayyid Thuwaini bin Shihab Al-Busaidi Represented by the Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Represented by the Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Represented by the Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Represented by the Representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.svg.png.webp) Personal Secretary for the Federal Councillor Pierre Combernous

Personal Secretary for the Federal Councillor Pierre Combernous

Pardons

To mark the funeral, the government pardoned 30,000 people convicted of minor criminal offenses. The pardons also allowed an additional 11 million people to recover such civil rights as the right to vote and run for public office, which they had lost as a punishment for offenses.[2]

Protests

The late emperor's funeral, like the man it honored, was dogged by bitter memories of the past. Many Allied veterans of World War II regarded Emperor Shōwa as a war criminal and called upon their countries to boycott the funeral.[6] Nevertheless, of the 166 foreign states invited to send representatives, all but three accepted.[8] Some Japanese, including a small Christian community, constitutional scholars and opposition politicians, denounced the pomp at the funeral as a return to past exaltation of the emperor and contended that the inclusion of Shinto rites violated Japan's post-war separation of church and state. Some groups, opposed to the Japanese monarchy, also staged small protests.[3]

The Shinto rites, witnessed by official funeral guests and held at the same site as the state-sponsored portion of the funeral, prompted criticism that the Government was violating the constitutional separation of state and religion. This separation is especially important in Japan because Shinto was used as the religious basis for the ultra-nationalism and militaristic expansion of wartime Japan. Some opposition party delegates to the funeral boycotted that part of the ceremony.[3] During the funeral procession in Tokyo, a man stepped into the street as the cortege approached. He was quickly apprehended by police who hustled him away.[2] At 1:55 pm, half an hour before the hearse carrying the late emperor's casket passed by, policemen patrolling the highway leading to the Musashi Imperial Graveyard heard an explosion and found debris scattered along the highway. They quickly cleared away the rubble, and the hearse passed without incident. In total, the police also arrested four people, two for trying to disrupt the procession.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ "Hirohito's survivors". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Ronald E. Yates, World Leaders Bid Hirohito Farewell, Chicago Tribune, 24 February 1989 (online) Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 13 Oct 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Susan Chira, With Pomp and on a Global Stage, Japanese Bury Emperor Hirohito, The New York Times, 24 February 1989 (online) Archived 8 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 13 Oct 2015

- ↑ Attali, Jacques, 1995, Verbatim, Volume 3, Fayard

- ↑ "Paying Respects: A Global Roll-Call". The New York Times. 24 February 1989. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- 1 2 Slavin, Stewart (20 February 1989). "Attending Hirohito funeral a touchy issue". UPI. United Press International. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ Meredith, Martin. The Fate of Africa: A History of the Continent Since Independence (Revised and Updated), p. 308.

- ↑ Schoenberger, Karl (24 February 1989). "World Leaders Pay Respects at Hirohito Rites". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021.