| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 11,747,400 (2011)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| India • Saudi Arabia • Pakistan • United Arab Emirates • United States of America • United Kingdom • Canada • Turkey | |

| Languages | |

| Urdu (the Deccani sub-dialect ) | |

| Religion | |

| Islam Majority Sunni (Sufi) Minority Shia (incl. Isma'ilism and Twelver Shi'ism) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tamil Muslims • Andhra Muslims • Marathi Muslims • Hyderabadi Muslims • Muhajir people • Other Indian Muslim communities |

The Deccanis or Deccani people are an ethnoreligious community of Deccani-speaking Muslims who inhabit or are from the Deccan region of Central and Southern India, and speak the Deccani dialect of Urdu.[2] The community traces its origins to the shifting of the Delhi Sultanate's capital from Delhi to Daulatabad in 1327 during the reign of Muhammad bin Tughluq.[3] Further ancestry can also be traced from immigrant Muslims referred to as Afaqis,[4] also known as Pardesis who came from Central Asia, Iraq and Iran and had settled in the Deccan region during the Bahmani Sultanate (1347). The migration of Muslim Hindavi-speaking people to the Deccan and intermarriage with the local Hindus whom converted to Islam,[5] led to the creation of a new community of Urdu-speaking Muslims, known as the Deccani, who would come to play an important role in the politics of the Deccan.[6] Their language, Deccani Urdu, emerged as a language of linguistic prestige and culture during the Bahmani Sultanate, further evolving in the Deccan Sultanates.[7]

Following the demise of the Bahmanis, the Deccan Sultanate period marked a golden age for Deccani culture, notably in the arts, language, and architecture.[8] The Deccani people form significant minority in the Deccan states of Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka, and form a majority in the old cities of Hyderabad and Aurangabad.[9][10] After the Partition of India and the annexation of Hyderabad, large diaspora communities formed outside the Deccan, especially in Pakistan, where they make up a significant portion of the Urdu speaking minority, the Muhajirs.[11]

The Deccani People are further divided into various groups, most notably the Hyderabadis (from Hyderabad Deccan), Mysoris (from Mysore state), and Madrasis (from Madras state) (including Kurnool, Nellore, Guntur, Chennai Muslims). Deccani Urdu is the mother-tongue of most Muslims in the states of Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and it is spoken by a section of Muslims from Tamil Nadu.

History

The word Deccani (Persian: دکنی from Prakrit dakkhin "south") was derived in the court of Bahmani rulers in 1487 AD during Sultan Mahmood Shah Bahmani II.[12]

A medieval Deccani Muslim horseman

A medieval Deccani Muslim horseman Map of the Bahmanid empire

Map of the Bahmanid empire

The Bahmanid empire was founded by Hasan Gangu, or also known as Zafar Khan, a ruler of Afghan or Turk origin. following the Rebellion of Ismail Mukh.[13][14][15][16][17][18] Hasan Gangu revolted against the Tughlaq dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate, with the revolt being led by another Afghan, named Ismail Mukh.[19] Ismail Mukh succeeded and then abdicated in favor of Zafar Khan, who founded the Bahmani Sultanate.[19][20] Hasan Gangu was one of the inhabitants of Delhi who were forced to immigrate to Daulatabad in the during the Delhi Sultanate, with the purpose of building a large Muslim urban centre in the Deccan.[21] These North Indian Urdu-speaking immigrants established an independent state, and eventually began adopting a distinct Deccani political identity.[22]

Though few in number, the Deccanis became disproportionately powerful in the Tamil and Telugu country because they included the soldiers and service people who constituted the region's first sizeable Muslim political elite.[23]

The Vijayanagara Wars

The Bahmanids' aggressive confrontation with the two main Hindu kingdoms of the southern Deccan, Warangal and Vijayanagar, made them renowned among Muslims as warriors of the faith.[24] Ahmad Shah Bahmani I conquered Warangal kingdom in 1425, annexing it to the empire. The Vijayanagar empire, which had subdued the Madurai Sultanate after a conflict lasting four decades, found a natural enemy in the Bahmanids of the northern Deccan, over the control of the Godavari-basin, Tungabadhra Doab, and the Marathwada country, although they seldom required a pretext for declaring war.[25] Military conflicts between the Bahmanids and Vijayanagara were almost a regular feature and lasted as long as these kingdoms continued. These military conflicts resulted in widespread devastation of the contested areas by both sides, resulting in considerable loss of life and property.[26] Military slavery involved captured slaves from Vijayanagar and having them embrace a Deccani identity by converting them to Islam and integrating into the host society, so they could begin military careers within the Bahmanid empire. This was the origin of powerful political leaders such as Nizam-ul-Mulk Bahri.[27][28]

Deccan Sultanates

The five Deccan Sultanates of diverse origins continued to identify as successor states of the Bahmanid dynasty as the basis of legitimacy, and minted Bahmanid coins rather than issue their own coins.[29] In their courts existed a shared identity group that was most associated with, and committed to their political system, known in Persian historiography as the Deccanis. The perspective of the Deccanis was largely responsible for the definition of the political landscape of the Deccan.[30] The Nizam Shahs and Berar Shahs were founded by the heads of the Deccani Muslim party.[31][32] The Adil Shahi Sultanate, which was founded by a Shia Georgian slave, also switched to a Deccani ethnic and political identity under Ibrahim Adil Shah I, who established Sunnism (the religion of the Deccani Muslims).[33][34] He degraded the Afaqis (Persians) and dismissed them from their posts with a few exceptions, replacing them with nobles of the Deccani party.[35][36][37][38] Uniting in a coalition under the leadership of Hussain Nizam Shah, the Nizam Shahi Sultan, the five Deccan Sultanates defeated the Hindu Vijayanagar empire in the Battle of Talikota, resulting in the Sack of Vijayanagara. Hussain Nizam Shah personally beheaded the Vijayanagar Emperor, Rama Raya.[39]

The Malik-i Maidan cannon

The Malik-i Maidan cannon.jpg.webp) Sultan Hussain Nizam Shah I beheads Rama Raya

Sultan Hussain Nizam Shah I beheads Rama Raya Ruins of Vijayanagar

Ruins of Vijayanagar

Pindaris

The first mention of the Pindaris referred to Muslim mercenaries generally settled in the districts of Bijapur, who had served as mercenaryies for the armies of most of the Muslim Deccani kingdoms. They took part in the numerous wars against the Mughals of Delhi. The disintgeration of the Muslim kingdoms of the Deccan led to the gradual disbandment of the Pindaris. These were at that stage taken in the service of the Marathas. The inclusion of the Pindaris eventually became an indispensable part and parcel of the Maratha army. As a class of freebooters in Maratha armies they acted as a "sort of roving cavalry...rendering them much the same service as the Cossacks for the armies of Russia." The Pindaris would also later be used by kings such as Tipu Sultan.[40]

18th century

Muslim military men with Dakhni background were much sought after by the Marava and Kallar warrior chiefs of the south Indian hinterland. Their fortress towns soon acquired concentrations of migrant Dakhnis and Urdu-speaking service people, mostly Sunnis. These incomers included seasoned fighters who had seen service with the Mughals and the Muslim states in northern India.[23] This was the source of the phenomenal rise of rulers such as Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan.

Sultanat-i-Khudadad of Mysore

Hyder Ali had initially served as an ordinary soldier for the Hindu Wadeyar Kingdom of Mysore and became a cavalry officer in 1749. As soon as Hyder Ali took control of the army, he took advantage of court politics, stormed into Srirangapatna and proclaimed himself ruler of Mysore. Having set up as a military dictator in 1761, Hyder Ali launched an unprovoked war against the Marathas, to divert the attention of the people from the sudden change of masters. With the withdrawal of Madhav Rao, he overran the Hindu principality of Bednur, Sunda and Karnuland its immense booty enormously increased Hyder Ali's power.[41] Tipu Sultan engaged in various forced conversions of Christians, including 7,000 British men and women who were help captive in the fort of Seringapatnam. One of these, James Scurry, recounted that he had forgotten how to sit on a chair, to use a knife and a fork, his English broken and stilted, and had developed an aversion to wearing European clothes.[42]

Territories of the original Wadeyar kingdom

Territories of the original Wadeyar kingdom Hyder's Dominions in 1780

Hyder's Dominions in 1780_(14761659876).jpg.webp) Hyder Ali as 'The Pretended Fakir'

Hyder Ali as 'The Pretended Fakir' Sir David Baird Discovering Body of Tipu Sultan

Sir David Baird Discovering Body of Tipu Sultan

Culture

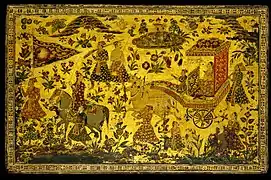

Painting

Deccani style painting originated in the 16th century in the Decccan region, containing an insightful native style with the blend of Persianate techniques and has a similarity of neighbouring Vijayanagara paintings. Due to the Islamic influence in the sultanate the Deccani paintings are mostly of nature with the background of floral and fauna, and the major use of regional landscape is reflected commonly with regional culture. Some Deccani paintings present the historical events of the region.[43][44]

Handicraft

The craftspersons of Bidar were so famed for their inlay work on copper and silver that it came to be known as Bidri.[45] It was developed in the 14th century C.E. during the rule of the Bahmani Sultans.[45] The term "bidriware" originates from the township of Bidar, which is still the chief center of production.[46] The Bidri ware is a Geographical Indication (GI) awarded craft of India.[45]

See also

Further reading

References

- ↑ "Deccani population statistics, 2011".

- ↑ "Kya ba so ba – Learning to speak south-indian urdu". www.zanyoutbursts.com. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ Aggarwal, Dr Malti Malik and Mala. Social Science. New Saraswati House India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-5199-083-3.

- ↑ "Āfāqī | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ↑ Eaton, Richard Maxwell (8 March 2015). The Sufis of Bijapur, 1300-1700: Social Roles of Sufis in Medieval India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6815-5.

- ↑ Burton, J. (February 1968). "V. N. Misra and M. S. Mate Indian prehistory: 1964. (Deccan College Building Centenary and Silver Jubilee Series, No.32.) xxiii, 264 pp. Poona: Deccan college postgraduate and Research Institute, 1965. Rs.15". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 31 (1): 162–164. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00113035. ISSN 0041-977X. S2CID 161064253.

- ↑ "Bahmani sultanate | historical Muslim state, India". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ "Sultans of Deccan India, 1500-1700 Opulence and Fantasy | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". metmuseum.org. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ "Urdu is the 2nd most spoken language in 5 states". The Siasat Daily. 2 September 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ↑ Eaton, Richard Maxwell (1996). Sufis of Bijapur, 1300 - 1700 : social roles of Sufis in medieval India (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publ. p. 41. ISBN 978-8121507400. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ Leonard, Karen Isaksen (1 January 2007). Locating Home: India's Hyderabadis Abroad. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804754422.

- ↑ Narendra Luther (1991). Prince;Poet;Lover;Builder: Mohd. Quli Qutb Shah - The founder of Hyderabad. Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. ISBN 9788123023151. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ Jenkins, Everett (2015). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 1, 570-1500): A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas, Volume 1. McFarland. p. 257. ISBN 9781476608884.

Zafar Khan alias Alauddin Hasan Gangu ('Ala al-Din Hasan Bahman Shah), an Afghan or a Turk soldier, revolted against Delhi and established the Muslim Kingdom of Bahmani on August 3 in the South (Madura) and ruled as Sultan Alauddin Bahman Shah.

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780415329200.

The Bahmani sultanate of the Deccan Soon after Muhammad Tughluq left Daulatabad, the city was conquered by Zafar Khan, a Turkish or Afghan officer of unknown descent, had earlier participated in a mutiny of troops in Gujarat.

- ↑ Wink, André (2020). The Making of the Indo-Islamic World C.700-1800 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9781108417747.

- ↑ Kerr, Gordon (2017). A Short History of India: From the Earliest Civilisations to Today's Economic Powerhouse. Oldcastle Books Ltd. p. 160. ISBN 9781843449232.

In the early fourteenth century, the Muslim Bahmani kingdom of the Deccan emerged following Alauddin's conquest of the south. Zafar Khan, an Afghan general and governor appointed by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq, was victorious against the troops of the Delhi Sultanate, establishing the Bahmani kingdom with its capital at Ahsanabad (modern-day Gulbarga).

- ↑ Scott, Jonathan (2016). Ferishta's History of Dekkan from the first Mahummedan conquests: with a continuation from other native writers, of the events in that part of India, to the reduction of its last monarchs by the emperor Aulumgeer Aurungzebe: also, the reigns of his successors in the empire of Hindoostan to the present day: and the history of Bengal, from the accession of Aliverdee Khan to the year 1780. hansebooks. p. 15. ISBN 9783743414709.

Some Authors write that he was descended from Bahman, one of the ancient kings of Persia. And I have seen a pedigree of him, fo derived (?), in the royal library of Ahmednagar: but am inclined to believe, such lineage was only framed upon his accession to royalty, by flatterers and poets, and that his origin is too obscure to be authentically traced. The apellation of Bahmani, he certainly took in compliment to Kango Brahmin, which is often pronounced Bhamen, and by tribe he was an Afghan.

- ↑ Wink, Andre (1991). Indo-Islamic society: 14th - 15th centuries. BRILL. p. 144. ISBN 9781843449232.

- 1 2 Ahmed Farooqui, Salma (2011). Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson. p. 150. ISBN 9789332500983.

- ↑ Ibrahim Khan (1960). Anecdotes from Islam. M. Ashraf.

- ↑ A. Rā Kulakarṇī; M. A. Nayeem; Teotonio R. De Souza (1996). Mediaeval Deccan History: Commemoration Volume in Honour of Purshottam Mahadeo Joshi. Popular Prakashan. p. 34. ISBN 9788171545797.

- ↑ Kousar.J. Azam (2017). Languages and Literary Cultures in Hyderabad. Taylor & Francis. p. 8. ISBN 9781351393997.

- 1 2 Keith E. Yandell Keith E. Yandell, John J. Paul (2013). Religion and Public Culture:Encounters and Identities in Modern South India. Taylor & Francis. p. 200. ISBN 9781136818011.

- ↑ Sheila Blair, Sheila S. Blair, Jonathan M. Bloom (25 September 1996). The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800. Yale University Press. p. 159. ISBN 0300064659.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ E. J. Brill (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 1072. ISBN 9789004097940.

- ↑ Medieval India UPSC Preparation Books History Series. Mocktime Publication. 2011.

- ↑ Richard M. Eaton (17 November 2005). A Social History of the Deccan, 1300-1761: Eight Indian Lives, Part 1, Volume 8. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780521254847.

- ↑ Roy S. Fischel (2020). Local States in an Imperial World. p. 72. ISBN 9781474436090.

- ↑ Pushkar Sohoni (2018). The Architecture of a Deccan Sultanate. Bloomsbury. p. 59. ISBN 9781838609283.

- ↑ Roy S. Fischel (2020). Local States in an Imperial World:Identity, Society and Politics in the Early Modern Deccan. Edinburgh University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781474436090.

- ↑ Sakkottai Krishnaswami Aiyangar (1951). Ancient India and South Indian History & Culture. Oriental Book Agency. p. 81.

- ↑ Thomas Wolseley Haig · (101). Historic Landmarks of the Deccan. Pioneer Press. p. 6.

- ↑ Navina Najat Haidar; Marika Sardar (13 April 2015). Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy (illustrated ed.). Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 6. ISBN 9780300211108.

- ↑ Shanti Sadiq Ali (1 January 1996). The African Dispersal in the Deccan: From Medieval to Modern Times. Orient Blackswan. p. 112. ISBN 9788125004851.

- ↑ Sanjay Subrahmanyam (2011). Three Ways to be Alien: Travails and Encounters in the Early Modern World (illustrated ed.). UPNE. p. 36. ISBN 9781611680195.

- ↑ Richard M. Eaton (17 November 2005). A Social History of the Deccan, 1300-1761: Eight Indian Lives, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780521254847.

- ↑ Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (1 January 2002). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 101. ISBN 9788126901234.

- ↑ Shihan de S. Jayasuriya; Richard Pankhurst (2003). The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean (illustrated ed.). Africa World Press. pp. 196–7. ISBN 9780865439801.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (12 April 2012). "Courtly Insults". Courtly Encounters : Translating Courtliness and Violence in Early Modern Eurasia. Harvard University Press. pp. 34–102. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674067363.c2. ISBN 978-0-674-06736-3.

- ↑ Roy, M.P. (1973). Origin growth and suppression of the Pindaris.

- ↑ Jaswant Lal Mehta (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707-1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. p. 457. ISBN 9781932705546.

- ↑ Ashok Rathore (2017). Impact of Christianity on Indian and Australian Societies. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781514494615.

- ↑ Deccani painting, britannica.com, 10 April 2012

- ↑ Mark Zebrowski (1983). Deccani Painting. University of California Press. pp. 40–285. ISBN 0-85667-153-3.

- 1 2 3 "Proving their mettle in metal craft". The Times of India. 2 January 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "Karnataka tableau to feature Bidriware". The Hindu. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2015.