The Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo) is a 1632 Italian-language book by Galileo Galilei comparing the Copernican system with the traditional Ptolemaic system. It was translated into Latin as Systema cosmicum[1] (Cosmic System) in 1635 by Matthias Bernegger.[2] The book was dedicated to Galileo's patron, Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who received the first printed copy on February 22, 1632.[3]

In the Copernican system, the Earth and other planets orbit the Sun, while in the Ptolemaic system, everything in the Universe circles around the Earth. The Dialogue was published in Florence under a formal license from the Inquisition. In 1633, Galileo was found to be "vehemently suspect of heresy" based on the book, which was then placed on the Index of Forbidden Books, from which it was not removed until 1835 (after the theories it discussed had been permitted in print in 1822).[4] In an action that was not announced at the time, the publication of anything else he had written or ever might write was also banned in Catholic countries.[5]

Overview

While writing the book, Galileo referred to it as his Dialogue on the Tides, and when the manuscript went to the Inquisition for approval, the title was Dialogue on the Ebb and Flow of the Sea. He was ordered to remove all mention of tides from the title and to change the preface because granting approval to such a title would look like approval of his theory of the tides using the motion of the Earth as proof. As a result, the formal title on the title page is Dialogue, which is followed by Galileo's name, academic posts, and followed by a long subtitle. The name by which the work is now known was extracted by the printer from the description on the title page when permission was given to reprint it with an approved preface by a Catholic theologian in 1744.[6] This must be kept in mind when discussing Galileo's motives for writing the book. Although the book is presented formally as a consideration of both systems (as it needed to be in order to be published at all), there is no question that the Copernican side gets the better of the argument.[7]

Structure

The book is presented as a series of discussions, over a span of four days, among two philosophers and a layman:

- Salviati argues for the Copernican position and presents some of Galileo's views directly, calling him the "Academician" in honor of Galileo's membership in the Accademia dei Lincei. He is named after Galileo's friend Filippo Salviati (1582–1614).

- Sagredo is an intelligent layman who is initially neutral. He is named after Galileo's friend Giovanni Francesco Sagredo (1571–1620).

- Simplicio, a dedicated follower of Ptolemy and Aristotle, presents the traditional views and the arguments against the Copernican position. He is supposedly named after Simplicius of Cilicia, a sixth-century commentator on Aristotle, but it was suspected the name was a double entendre, as the Italian for "simple" (as in "simple minded") is "semplice".[8] Simplicio is modeled on two contemporary conservative philosophers, Lodovico delle Colombe (1565–1616?), Galileo's opponent, and Cesare Cremonini (1550–1631), a Paduan colleague who had refused to look through the telescope.[9] Colombe was the leader of a group of Florentine opponents of Galileo's, which some of the latter's friends referred to as "the pigeon league".[10]

Content

The discussion is not narrowly limited to astronomical topics, but ranges over much of contemporary science. Some of this is to show what Galileo considered good science, such as the discussion of William Gilbert's work on magnetism. Other parts are important to the debate, answering erroneous arguments against the Earth's motion.

A classic argument against Earth motion is the lack of speed sensations of the Earth surface, though it moves, by the Earth's rotation, at about 1700 km/h at the equator. In this category there is a thought experiment in which a man is below decks on a ship and cannot tell whether the ship is docked or is moving smoothly through the water: he observes water dripping from a bottle, fish swimming in a tank, butterflies flying, and so on; and their behavior is the same whether the ship is moving or not. This is a classic exposition of the inertial frame of reference and refutes the objection that if we were moving hundreds of kilometres an hour as the Earth rotated, anything that one dropped would rapidly fall behind and drift to the west.

The bulk of Galileo's arguments may be divided into three classes:

- Rebuttals to the objections raised by traditional philosophers; for example, the thought experiment on the ship.

- Observations that are incompatible with the Ptolemaic model: the phases of Venus, for instance, which simply could not happen, or the apparent motions of sunspots, which could only be explained in the Ptolemaic or Tychonic systems as resulting from an implausibly complicated precession of the Sun's axis of rotation.[11]

- Arguments showing that the elegant unified theory of the Heavens that the philosophers held, which was believed to prove that the Earth was stationary, was incorrect; for instance, the mountains of the Moon, the moons of Jupiter, and the very existence of sunspots, none of which was part of the old astronomy.

Generally, these arguments have held up well in terms of the knowledge of the next four centuries. Just how convincing they ought to have been to an impartial reader in 1632 remains a contentious issue.

Galileo attempted a fourth class of argument:

- Direct physical argument for the Earth's motion, by means of an explanation of tides.

As an account of the causation of tides or a proof of the Earth's motion, it is a failure. The fundamental argument is internally inconsistent and actually leads to the conclusion that tides do not exist. But, Galileo was fond of the argument and devoted the "Fourth Day" of the discussion to it. The degree of its failure is—like nearly anything having to do with Galileo—a matter of controversy. On the one hand, the whole thing has recently been described in print as "cockamamie."[12] On the other hand, Einstein used a rather different description:

It was Galileo's longing for a mechanical proof of the motion of the earth which misled him into formulating a wrong theory of the tides. The fascinating arguments in the last conversation would hardly have been accepted as proof by Galileo, had his temperament not got the better of him. [Emphasis added][13][14]

Omissions

The Dialogue does not treat the Tychonic system, which was becoming the preferred system of many astronomers at the time of publication and which was ultimately proven incorrect. The Tychonic system is a motionless Earth system but not a Ptolemaic system; it is a hybrid system of the Copernican and Ptolemaic models. Mercury and Venus orbit the Sun (as in the Copernican system) in small circles, while the Sun in turn orbits a stationary Earth; Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn orbit the Sun in much larger circles, which means they also orbit the Earth. The Tychonian system is mathematically equivalent to the Copernican system, except that the Copernican system predicts a stellar parallax, while the Tychonian system predicts none. Stellar parallax was not measurable until the 19th century, and therefore there was at the time no valid disproof of the Tychonic system on empirical grounds, nor any decisive observational evidence for the Copernican system.

Galileo never took Tycho's system seriously, as can be seen in his correspondence, regarding it as an inadequate and physically unsatisfactory compromise. A reason for the absence of Tycho's system (in spite of many references to Tycho and his work in the book) may be sought in Galileo's theory of the tides, which provided the original title and organizing principle of the Dialogue. While the Copernican and Tychonic systems are equivalent geometrically, they are quite different dynamically. Galileo's tidal theory entailed the actual, physical movement of the Earth; that is, if true, it would have provided the kind of proof that Foucault's pendulum apparently provided two centuries later. Without reference to Galileo's tidal theory, there would be no difference between the Copernican and Tychonic systems.

Galileo also fails to discuss the possibility of non-circular orbits, although Johannes Kepler had sent him a copy of his 1609 book, Astronomia nova, in which he proposes elliptical orbits—correctly calculating that of Mars.[15] Prince Federico Cesi's letter to Galileo of 1612 treated the two laws of planetary motion presented in the book as common knowledge;[16][17] Kepler's third law was published in 1619. Four and a half decades after Galileo's death, Isaac Newton published his laws of motion and gravity, from which a heliocentric system with planets in approximately elliptical orbits is deducible.

Summary

Preface: To the Discerning Reader refers to the ban on the "Pythagorean opinion that the earth moves" and says that the author "takes the Copernican side with a pure mathematical hypothesis". He introduces the friends Sagredo and Salviati with whom he had had discussions as well as the peripatetic philosopher Simplicio.

Day one

He starts with Aristotle's proof of the completeness and perfection of the world (i.e. the universe) because of its three dimensions. Simplicio points out that three was favoured by the Pythagoreans whereas Salviati cannot understand why three legs are better than two or four. He suggests that the numbers were "trifles which later spread among the vulgar" and that their definitions, such as those of straight lines and right angles, were more useful in establishing the dimensions. Simplicio's response was that Aristotle thought that in physical matters mathematical demonstration was not always needed.

Salviati attacks Aristotle's definition of the heavens as incorruptible and unchanging whilst only the lunar-bound zone shows change. He points to the changes seen in the skies: the new stars of 1572 and 1604 and sunspots, seen through the new telescope. There is a discussion about Aristotle's use of a priori arguments. Salviati suggests that Arisotle uses Aristotle’s personal experience to choose an appropriate argument to prove just as others do and that Aristotle would change his mind in the present circumstances.

Simplicio argues that sunspots could simply be small opaque objects passing in front of the Sun, but Salviati points out that some appear or disappear randomly and those at the edge are flattened, unlike separate bodies. Therefore, "it is better Aristotelian philosophy to say 'Heaven is alterable because my senses tell me' than 'Heaven is unalterable because Aristotle was so persuaded by reasoning.'"

Experiments with a mirror are used to show that the Moon's surface must be opaque and not a perfect crystal sphere as Simplicio believes. He refuses to accept that mountains on the Moon cause shadows, or that reflected light from the Earth is responsible for the faint outline in a crescent moon.

Sagredo holds that he considers the Earth noble because of the changes in it whereas Simplicio says that change in the Moon or stars would be useless because they do not benefit man. Salviati points out that days on the moon are a month long and despite the varied terrain that the telescope has disclosed, it would not sustain life. Humans acquire mathematical truths slowly and hesitantly, whereas God knows the full infinity of them intuitively. And when one looks into the marvellous things men have understood and contrived, then clearly the human mind is one of the most excellent of God's works.

Day two

The second day starts by repeating that Aristotle would be changing his opinions if he saw what they were seeing. "It is the followers of Aristotle who have crowned him with authority, not he who has usurped or appropriated it to himself."

There is one supreme motion—that by which the Sun, Moon, planets and fixed stars appear to be moved from east to west in the space of 24 hours. This may as logically belong to the Earth alone as to the rest of the universe. Aristotle and Ptolemy, who understood this, do not argue against any other motion than this diurnal one.

Motion is relative: the position of the sacks of grain on a ship can be identical at the end of the voyage despite the movement of the ship. Why should we believe that nature moves all these extremely large bodies with inconceivable velocities rather than simply moving the moderately sized earth? If the Earth is removed from the picture, what happens to all the movement?

The movement of the skies from east to west is the opposite of all the other motions of the heavenly bodies which are from west to east; making the Earth rotate brings it into line with all the others. Although Aristotle argues that circular motions are not contraries, they could still lead to collisions.

The great orbits of the planets take longer than the shorter: Saturn and Jupiter take many years, Mars two, whereas the Moon takes only a month. Jupiter's moons take even less. This is not changed if the Earth rotates every day, but if the Earth is stationary then we suddenly find that the sphere of the fixed stars rotates in 24 hours. Given the distances, that would more reasonably be thousands of years.

In addition some of these stars have to travel faster than others: if the Pole Star was precisely at the axis, then it would be entirely stationary whereas those of the equator have unimaginable speed. The solidity of this supposed sphere is incomprehensible. Make the earth the primum mobile and the need for this extra sphere disappears.

They consider three main objections to the motion of the Earth: that a falling body would be left behind by the Earth and thus fall far to the west of its point of release; that a cannonball fired to the west would similarly fly much further than one fired to the east; and that a cannonball fired vertically would also land far to the west. Salviati shows that these do not take account of the impetus of the cannon.

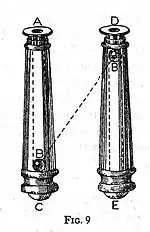

He also points out that attempting to prove that the Earth does not move by using vertical fall commits the logical fault of paralogism (assuming what is to be proved), because if the Earth is moving then it is only in appearance that it is falling vertically; in fact it is falling at a slant, as happens with a cannonball rising through the cannon (illustrated).

In rebutting a work which claims that a ball falling from the Moon would take six days to arrive, the odd-number rule is introduced: a body falling 1 unit in an interval would fall 3 units in the next interval, 5 units in the subsequent one, etc. This gives rise to the rule by which the distance fallen is according to the square of the time. Using this he calculates the time is really little more than 3 hours. He also points out that density of the material does not make much difference: a lead ball might only accelerate twice as fast as one of cork.

In fact, a ball falling from such a height would not fall behind but ahead of the vertical because the rotational motion would be in ever-decreasing circles. What makes the Earth move is similar to whatever moves Mars or Jupiter and is the same as that which pulls the stone to Earth. Calling it gravity does not explain what it is.

Day three

Salviati starts by dismissing the arguments of a book against the novas he has been reading overnight.[18] Unlike comets, these were stationary and their lack of parallax easily checked and thus could not have been in the sublunary sphere.

Simplicio now gives the greatest argument against the annual motion of the Earth that if it moves then it can no longer be the center of the zodiac, the world. Aristotle gives proofs that the universe is finite bounded and spherical. Salviati points out that these disappear if he denies him the assumption that it is movable, but allows the assumption initially in order not to multiply disputes.

He points out that if anything is the centre, it must be the Sun not the Earth, because all the planets are closer or further away from the Earth at different times, Venus and Mars up to eight times. He encourages Simplicio to make a plan of the planets, starting with Venus and Mercury which are easily seen to rotate about the Sun. Mars must also go about the Sun (as well as the Earth) since it is never seen horned, unlike Venus now seen through the telescope; similarly with Jupiter and Saturn. Earth, which is between Mars with a period of two years and Venus with nine months, has a period of a year which may more elegantly be attributed to motion than a state of rest.

Sagredo brings up two other common objections. If the Earth rotated, the mountains would soon be in a position that one would have to descend them rather than ascend. Secondly, the motion would be so rapid that someone at the bottom of a well would have only a brief instance to glimpse a star as it traversed. Simplicio can see that the first is no different from travelling over the globe, as any who have circumnavigated but though he realises the second is the same as if the heavens were rotating, he still does not understand it. Salviati says the first is no different from those who deny the antipodes. For the second, he encourages Simplicio to decide what fraction of the sky can be seen from down the well.

Salviati brings up another problem, which is that Mars and Venus are not as variable as the theory would suggest. He explains that the size of a star to the human eye is affected by the brightness and the sizes are not real. This is resolved by use of the telescope which also shows the crescent shape of Venus. A further objection to the movement of the Earth, the unique existence of the Moon, has been resolved by the discovery of the moons of Jupiter, which would appear like Earth's Moon to any Jovian.

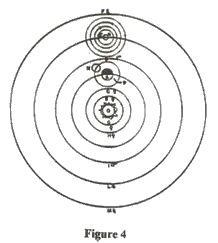

Copernicus has succeeded in reducing some of the uneven motions of Ptolemy who had to deal with motions that sometimes go fast, sometimes slow, and sometimes backwards, by means of vast epicycles. Mars, above the Sun's sphere, often falls far below it, then soars above it. These anomalies are cured by the annual movement of the Earth. This is explained by a diagram in which the varying motion of Jupiter is shown using the Earth's orbit.

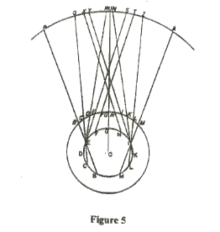

Simplicio produces another booklet in which theological arguments are mixed with astronomic, but Salviati refuses to address the issues from Scripture. So he produces the argument that the fixed stars must be at an inconceivable distance with the smallest larger than the whole orbit of the Earth. Salviati explains that this all comes from a misrepresentation of what Copernicus said, resulting in a huge over-calculation of the size of a sixth magnitude star. But many other famous astronomers over-estimated the size of stars by ignoring the brightness factor. Not even Tycho, with his accurate instruments, set himself to measure the size of any star except the Sun and Moon. But Salviati (Galileo) was able to make a reasonable estimate simply by hanging a cord to obscure the star and measuring the distance from eye to cord.

But still many cannot believe that the fixed stars can individually be as big or bigger than the Sun. To what end are these? Salviati maintains that "it is brash for our feebleness to attempt to judge the reasons for God's actions, and to call everything in the universe vain and superfluous which does not serve us".

Has Tycho or any of his disciples tried to investigate in any way phenomena that might affirm or deny the movement of the Earth? Do any of them know how much variation is needed in the fixed stars? Simplicio objects to conceding that the distance of the fixed stars is too great for it to be detectable. Salviati points out how difficult it is even to detect the varying distances of Saturn. Many of the positions of the fixed stars are not known accurately and far better instruments than Tycho's are needed: say using a sight with a fixed position 60 miles away.

Sagredo then asks Salviati to explain how the Copernican system explains the seasons and inequalities of night and day. This he does with the aid of a diagram showing the position of the Earth in the four seasons. He points out how much simpler it is than the Ptolemaic system. But Simplicio thinks Aristotle was wise to avoid too much geometry. He prefers Aristotle's axiom to avoid more than one simple motion at a time.

Day four

They are in Sagredo's house in Venice, where tides are an important issue, and Salviati wants to show the effect of the Earth's movement on the tides. He first points out the three periods of the tides: daily (diurnal), generally with intervals of 6 hours of rising and six more of falling; monthly, seemingly from the Moon, which increases or decreases these tides; and annual, leading to different sizes at the equinoxes.

He considers first the daily motion. Three varieties are observed: in some places the waters rise and fall without any forward motion; in others they move towards the east and back to the west without rising or falling; in still others there is a combination of both—this happens in Venice where the waters rise on entering and fall on leaving. In the Straits of Messina there are very swift currents between Scylla and Charybdis. In the open Mediterranean the alteration of height is small but the currents are noticeable.

Simplicio counters with the peripatetic explanations, which are based on the depths of the sea, and the dominion of the Moon over the water, though this does not explain the risings when the Moon is below the horizon. But he admits it could be a miracle.

When the water in Venice rises, where does it come from? There is little rise in Corfu or Dubrovnik. From the ocean through the Straits of Gibraltar? It's much too far away and the currents are too slow.

So could the movement of the container cause the disturbance? Consider the barges that bring water into Venice. When they hit an obstacle, the water rushes forward; when they speed up it will go to the back. For all this disturbance there is no need for new water and the level in the middle stays largely constant though the water there rushes backwards and forwards.

Consider a point on the Earth under the joint action of the annual and diurnal movements. At one time these are added together and 12 hours later they act against each other, so there is an alternate speeding up and slowing down. So the ocean basins are affected in the same way as the barge particularly in an east-west direction. The length of the barge makes a difference to the speed of oscillations, just as the length of a plumb bob changes its speed. The depth of water also makes a difference to the size of vibrations.

The primary effect only explains tides once a day; one must look elsewhere for the six-hour change, to the oscillation periods of the water. In some places, such as the Hellespont and the Aegean the periods are briefer and variable. But a north-south sea like the Red Sea has very little tide whereas the Messina Strait carries the pent up effect of two basins.

Simplicio objects that if this accounts for the water, should it not even more be seen in the winds? Salviati suggests that the containing basins are not so effective and the air does not sustain its motion. Nevertheless, these forces are seen by the steady winds from east to west in the oceans in the tropical zone.

It seems that the Moon also is taking part in the production of the daily effects, but that is repugnant to his mind. The motions of the Moon have caused great difficulty to astronomers. It's impossible to make a full account of these things given the irregular nature of the sea basins.

See also

- "Discourse on the Tides", 1616 Galileo essay

Notes

- ↑ Maurice A. Finocchiaro: Retrying Galileo, 1633-1992, University of California Press, 2007 ISBN 0-520-25387-6, ISBN 978-0-520-25387-2

- ↑ Journal for the history of astronomy, 2005

- ↑ Gindikin, Semen Grigorʹevich (1988). Tales of physicists and mathematicians. Birkhäuser. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8176-3317-2. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ↑ The Trial of Galileo: A Chronology Archived 2007-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ See Galileo affair for more details, including sources.

- ↑ Drake, Stillman (1990). Galileo: Pioneer Scientist. U of Toronto Press. p. 187. ISBN 0-8020-2725-3.

- ↑ Koestler, Arthur (1989). The Sleepwalkers. Penguin Arkana. p. 480. ISBN 9780140192469.

- ↑ Arthur Koestler, The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe (1959), Penguin Books, 1986 edition: ISBN 0-14-055212-X, 978014055212X 1990 reprint: ISBN 0-14-019246-8, ISBN 978-0-14-019246-9

- ↑ Stillman Drake: Galileo at Work: His Scientific Biography, Courier Dover Publications, 2003, ISBN 0-486-49542-6, page 355 : Cremonini and delle Colombe

- ↑ "La legha del pippione". "Pippione" is a pun on Colombe's surname—which is the plural of the Italian word for dove. Galileo's friends, the painter, Lodovico Cardi da Cigoli (in Italian), his former student, Benedetto Castelli, and a couple of his other correspondents often referred to Colombe as "il Colombo", which means "the Pigeon". Galileo himself used this term a couple of times in a letter to Cigoli of October, 1611 (Edizione Nazionale 11:214). The more derisive nickname, "il Pippione", sometimes used by Cigoli (Edizione Nazionale 11:176, 11:229, 11:476,11:502), is a now archaic Italian word with a triple entendre. Besides meaning "young pigeon", it is also a jocular term for a testicle, and a Tuscan dialect word for a fool.

- ↑ Drake, (1970, pp. 191–196), Linton (2004, pp. 211–12), Sharratt (1994, p. 166). This is not true, however, for geocentric systems—such as that proposed by Longomontanus—in which the Earth rotated. In such systems the apparent motion of sunspots could be accounted for just as easily as in Copernicus's.

- ↑ Timothy Moy (September 2001). "Science, Religion, and the Galileo Affair". Skeptical Inquirer. 25 (5): 43–49. Archived from the original on January 29, 2009.

- ↑ "Foreword; By Albert Einstein; Authorized Translation by Sonja Bargmann". Archived from the original on 2007-09-25.(passages omitted)

- ↑ Paul Mainwood (9 August 2003). "Thought Experiments in Galileo and Newton's Mathematical Philosophy" (PDF). 7th Annual Oxford Philosophy Graduate Conference. 7th Annual Oxford Philosophy Graduate Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 22, 2006., quoting page xvii of Einstein's foreword in G. Galilei (1953) [1632]. Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. Translated by Stillman Drake. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: The University of California Press.

- ↑ Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

- ↑ Galileo's Opere, Ed.Naz., XI (Florence 1901) pp. 365–367

- ↑ "Kepler", by Max Caspar, p. 137

- ↑ Chiaramonti, Scipio (1628). De tribus novis stellis.

Bibliography

- Drake, Stillman (1970). Galileo Studies. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08283-3.

- Linton, Christopher M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein – A History of Mathematical Astronomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82750-8.

- Sharratt, Michael (1994). Galileo: Decisive Innovator. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56671-1.

External links

Media related to Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo at Wikimedia Commons

- Italian text with figures (in Italian)

- Thomas Salusbury's 1661 English translation of the Dialogue. On-line copy of full text.

- Dialogo dei massimi sistemi. Fiorenza, Per Gio: Batista Landini, 1632. From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Audio book version by Brian Keating