| Diamond Head | |

|---|---|

Diamond Head cone seen from Tantalus-Round Top Road | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 762 ft (232 m)[1] |

| Prominence | 596 ft (182 m)[2] |

| Coordinates | 21°15′43″N 157°48′20″W / 21.26194°N 157.80556°W |

| Geography | |

Diamond Head | |

| Location | Honolulu, Hawaii, US |

| Parent range | Hawaiian Islands |

| Topo map | USGS Honolulu |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 200,000 years |

| Mountain type | Volcanic cone |

| Last eruption | Unknown |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Trail |

| Designated | 1968 |

Diamond Head is a volcanic tuff cone on the Hawaiian island of Oʻahu and known to Hawaiians as Lēʻahi (pronounced [leːˈʔɐhi]). The Hawaiian name is most likely derived from lae (browridge, promontory) plus ʻahi (tuna) because the shape of the ridgeline resembles the shape of a tuna's dorsal fin.[3] Its English name was given by British sailors in the 19th century, who named it for the calcite crystals on the adjacent beach.

Geology

Diamond Head is part of the system of cones, vents, and their associated eruption flows that are collectively known to geologists as the Honolulu Volcanic Series, formed by renewed eruptions from the Koʻolau Volcano that took place long after the volcano formed and had gone dormant. These eruptive events created many of Oʻahu's well-known landmarks, including Punchbowl Crater, Hanauma Bay, Koko Head, and Mānana Island.

Like the rest of the Honolulu Volcanic Series, Diamond Head is much younger than the main mass of the Koʻolau Mountain Range. While the Koʻolau Range is about 2.6 million years old, Diamond Head is estimated to be about 400,000 to 500,000 years old.[4]

History

Known as Lēʻahi in Hawaiian, the mountain was given the name Diamond Hill in 1825 by British sailors who discovered sparkling volcanic calcite crystals in the sand and mistook them for diamonds. This is reflected in another local name, Kaimana Hila. The name later became Diamond Head, with head being shortened from headland.[5]

The interior and adjacent exterior areas were the home to Fort Ruger,[6] the first United States military reservation on Hawaii.[7] Only Battery 407, a National Guard emergency operations center, and Birkhimer Tunnel, the Hawaii State Civil Defense Headquarters (HI-EMA), remain in use in the crater.[7] An FAA air traffic control center was in operation from 1963 to 2002.[8]

Tourism

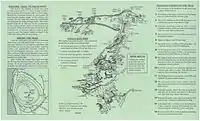

Diamond Head is a defining feature of the view known to residents and tourists of Waikīkī, and also a U.S. National Natural Monument. The volcanic tuff cone is a State Monument. While part of it is closed to the public and serves as a platform for antennas used by the U.S. government, the crater's proximity to Honolulu's resort hotels and beaches makes the rest of it a popular destination.

National Natural Landmark

In 1968, Diamond Head was declared a National Natural Landmark. The crater, also called Diamond Head Lookout, was used as a strategic military lookout in the early 1900s.[6] Spanning over 475 acres (190 ha) (including the crater's interior and outer slopes), it served as an effective defensive lookout because it provides panoramic views of Waikīkī and the south shore of Oahu.[9]

The Diamond Head Lighthouse, a navigational lighthouse built in 1917 is directly adjacent to the crater's slopes.[6] In addition, a few pillboxes are on Diamond Head's summit.[6]

In popular culture

Diamond Head appears on an 80-cent air mail stamp issued in 1952 to pay for shipping orchids to the U.S. mainland.[10]

Charlton Heston stars in the 1963 film Diamond Head., in a role that Clark Cable was supposed to play.

A 1975 televised game show, The Diamond Head Game, was set at Diamond Head.[11]

The Crater was the location of several concerts in the 1960s and 1970s.[12] First held on New Year's Day 1969, and often known as Hawaiian Woodstock, Diamond Head Crater Festivals, sometimes called Sunshine Festivals, were all-day music celebrations held in the 1960s and '70s, attracting over 75,000 attendees for performances of the Grateful Dead, Santana, America, Styx, Journey, War, and Tower of Power, alongside Hawaiian talent like Cecilio & Kapono and the Mackey Feary Band.[12][13][14][15] The one-day festivals became two-day events in 1976 and 1977, but were canceled by the Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources because of community noise and environmental impact concerns.[14] Many items from the bands were brought into and out of the Crater by helicopter.[14]

- Various views of Diamond Head

A view from the ocean of Diamond Head

A view from the ocean of Diamond Head Diamond Head cone seen from the coast off Waikīkī

Diamond Head cone seen from the coast off Waikīkī View from Rocky Hill, which resides over Punahou School

View from Rocky Hill, which resides over Punahou School Diamond Head peak from Kapiolani Park

Diamond Head peak from Kapiolani Park Diamond Head seen from Waikīkī in the 1800s

Diamond Head seen from Waikīkī in the 1800s Waikiki Beach facing Diamond Head, 1958

Waikiki Beach facing Diamond Head, 1958

Aerial view of the Diamond Head

Aerial view of the Diamond Head A view from the south, including Diamond Head Lighthouse

A view from the south, including Diamond Head Lighthouse

See also

References

- ↑ "USGS Topo map".

- ↑ "Diamond Head". Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ↑ Mary Kawena Pukui, Samuel H. Elbert, Esther K. Mookini, eds. (1964). Place Names of Hawaii, revised and expanded edition. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 0-8248-0524-0.

- ↑ "A geologic tour of the Hawaiian Islands: Oʻahu". HVO Volcano Watch. USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. January 14, 2016. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ↑ John R. K. Clark (2002). Hawai'i Place Names: Shores, Beaches, and Surf Sites. University of Hawaii Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8248-2451-8.

- 1 2 3 4 "American Seacoast Defenses Forts, Military Reservations and Batteries 1794-1956: Oahu 1922" (PDF). Coast Defense Study Group (cdsg.org). Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- 1 2 Fawcett, Denby (August 3, 2014). "Tunnel Vision". Star-Advertiser. Honolulu. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018. Alt URL

- ↑ FAA quits Diamond Head crater

- ↑ "Diamond Head Lookout". Pearl Harbor Website. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ US Airmail Stamps 1941-1961

- ↑ "The Diamond Head Game" (1975)

- 1 2 "Diamond Head State Monument Honolulu Concert Setlists". setlist.fm. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ↑ Borreca, Richard (November 1, 1999). "Rebellion & Renaissance, Groovin' in the crater with music and mindbenders: In the '60s and '70s, music moves Hawaii's youth to come together and to speak out". Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Dekneef, Matthew (April 20, 2016). "Memories of the Diamond Head Crater Festivals, Hawaii's own 'Woodstock'". Hawai'i Magazine. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ↑ "Do You Remember... Crater Festivals". Midlife Crisis Hawaii. March 22, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

External links

- Official website Hawaii State Parks - Diamond Head State Monument

Geographic data related to Diamond Head, Hawaii at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Diamond Head, Hawaii at OpenStreetMap- Satellite image of Diamond Head (Google Maps)