A dish structure is a type of sedimentary structure formed by liquefaction and fluidization of water-charged soft sediment either during or immediately following deposition.

Terminology

Due to the similarity in its shape to a dish, the structure, sometimes also referred to as dish-and-pillar or dish-and-pipe , was named after the common kitchen item.

History

Dish structure was described scientifically for the first time by Crook in 1961[1] who still used the title discontinuous curved lamination. The established term was used for the first time in 1967 by Stauffer[2] and by Wentworth.[3] Comprehensive studies are due to Lowe and LoPiccolo in 1974 and Lowe in 1975.[4]

Description

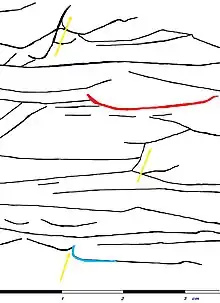

The subhorizontal dish structure consists of two parts, the dish itself and the [sediment] contained within the dish plus the region stretching up to the bounding surface of the overlying dish(or dishes) above. The bounding surface of the dish can take on variable shapes, from substantially flat to bowl-like and to strongly concave up. The bounding surfaces are thin, (and usually) dark(er) laminae; they are richer in clay, silt or organic material than the surrounding sediment. The individual dishes are arranged en echelon. Their width can vary from 2 centimeters to over 50 centimeters, the vertical spacing ranges usually from less than 1 centimeter to about 8 centimeters. Their plan shape grades from circular/polygonal to oval/elliptical. Their bases are sharp, but the tops are gradational.

Commonly the dishes are separated by vertical streaks of massive sand called 'pillars'. These pillars can be small-scale structures (Type A pillars) or large and throughgoing high-discharge structures (Type B pillars).

Within an individual bed an increase in concavity combined with a simultaneous decrease in width of the dishes can often be observed towards the top.

Occurrence

Dish structure occurs in laterally extensive sheets. The medium in which the structure forms is usually coarse silt, but it also appears in all grades of sand. They are never found in gravels nor in clays. The containing beds are normally graded. The depositional environment of the structure is mainly deep-water marine (i.e. continental rise) comprising coarser grained turbidity currents and related high-concentration flows (grain flows, fluidized flows, liquefied flows). But dish structure can also be encountered in shallow-marine deposits and in fluviatile, lacustrine and delta environments.[5] It is occasionally found in ash layers within marine sediments.

In turbidites dish structure usually forms within Bouma C, occasionally also within Bouma B.

Good examples of dish structure can be seen for instance in the Jack Fork Group in Oklahoma, in Ordovician turbidites at Cardigan in Wales, in deep-sea fan deposits near San Sebastián in Spain and in the Cerro Torro Formation of southern Chile. Some of the largest dish structure is found near Talara in northern Peru.

Formation

Up to 1974 dish structure was still regarded as a primary sedimentary structure. The formation of the structure was thought to be related either to the mechanics of sediment transport or to deposition in high-concentration gravity-flows. Only since Lowe and LoPiccolos's study, the structure is recognized as penecontemporaneous or secondary, formed during the dewatering of rapidly deposited quick or underconsolidated beds.[6]

The postdepositional character of dish structure can sometimes clearly be seen in cut or displaced primary sedimentary structures (like convolute-laminated beds). During the dewatering process less permeable horizons (richer in small grain sizes like dispersed mud) act as barriers to upward flow; the flow is consequently forced sideways until an upward escape is possible. The sideways directed fluid motion has the tendency to leave fines along the low-permeability barriers which eventually become the clay-enriched laminae of the dishes. When the fluid finally finds a possibility to escape vertically it turns up the edges of the dishes. More forceful upward flow creates pillars – which are essentially dewatering pipes.

Use

Dish structure is a powerful means to recognize the younging direction in sediments.

References

- ↑ K. A. W. Crook (1961). In: J. Proc. R. Soc. N.S.W., 94, p. 189 – 207

- ↑ P. H. Stauffer (1967). Grain flow deposits and their implications, Santa Ynes Mountains, California. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 32, p. 487-508

- ↑ C. M. Wentworth (1967). Dish structure, a primary sedimentary structure and coarse turbidites. Am. Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Bull., 51, p. 85 -96

- ↑ D. R. Lowe (1975). Water escape structures in coarse-grained sediments. Sedimentology, 22, p. 157 – 204

- ↑ T. H. Nilsen et al. (1977). New occurrence of dish structure in the stratigraphic record. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 47, p. 1299–1304

- ↑ D. R. Lowe & R. D. LoPiccolo (1974). The characteristics and origins of dish and pillar structures. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 44, p. 484 – 501

Literature

- J. R. L. Allen (1984). Sedimentary structures. Their character and physical basis. Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-42232-3

- M. E. Leeder (1999). Sedimentology and Sedimentary Basins. Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-04976-6

- H.-E. Reineck & I.B. Singh (1980). Depositional Sedimentary Environments. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-10189-6