| Dorudon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dorudon atrox, Senckenberg Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | †Basilosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Dorudontinae |

| Genus: | †Dorudon Gibbes 1845 |

| Species[1] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

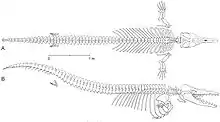

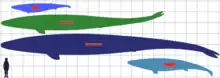

Dorudon ("spear-tooth") is a genus of extinct basilosaurid ancient whales that lived alongside Basilosaurus 40.4 to 33.9 million years ago in the Eocene. It was a small whale, with D. atrox measuring 5 metres (16 ft) long and weighing 1–2.2 metric tons (1.1–2.4 short tons). Dorudon lived in warm seas around the world and fed on small fish and mollusks. Fossils have been found along the former shorelines of the Tethys Sea in present-day Egypt and Pakistan, as well as in the United States, New Zealand and Western Sahara.[1]

Taxonomic history

Gibbes 1845 described Dorudon serratus based on a fragmentary maxilla and a few teeth found in South Carolina. He concluded that the teeth must have belonged to a mammal since they were two-rooted, that they must have been teeth from a juvenile since they were hollow, and also noted their similarity to the teeth then described for Zeuglodon (Basilosaurus).[4] When exploring the type locality, Gibbes discovered a lower jaw and twelve caudal vertebrae, which he felt obliged to assign to Zeuglodon together with his original material. Gibbes concluded that Dorudon were juvenile Zeuglodon and consequently withdrew his new genus. He did, however, allow Louis Agassiz at Harvard to examine his specimens, and the Swiss professor replied that these were neither teeth of a juvenile nor those of Zeuglodon, but of a separate genus just as Gibbes had first proposed.[5]

Andrews 1906 described Prozeuglodon atrox (="Proto-Basilosaurus") based on a nearly complete skull, a dentary and three associated vertebrae presented to him by the Geological Museum of Cairo.[2] Kellogg 1936,[6] however, realized that Andrews' specimen was a juvenile, and, he assumed, the same species as Zeuglodon isis, described by Andrews 1906. Kellogg also realized that the generic name Zeuglodon was invalid and therefore recombined it Prozeuglodon isis.[7] Since then many specimens have been referred to Prozeuglodon atrox, including virtually every part of the skeleton, and it has become obvious that it is a separate genus, not a juvenile "Proto-Zeuglodon".[7][8] Kellogg placed several of the species of Zeuglodon described from Egypt in the early 20th century (including Z. osiris, Z. zitteli, Z. elliotsmithii and Z. sensitivius) in the genus Dorudon. Gingerich 1992 synonymized these four species and grouped them as Saghacetus osiris.[7]

The current taxonomic status of Dorudon is based on Uhen 2004's revision of Dorudon and detailed description of D. atrox. Before this, the taxonomy of Dorudon was in disarray and based on a limited set of specimens.

D. atrox is known from Egypt,[9] D. serratus from Georgia and South Carolina in the United States.[10] The type species D. serratus was, and still is, based solely on two partial maxillae with a few teeth, cranial fragments, and a dozen vertebrae with some additional material, collected but not described by Gibbes, and referred to the type species. Before Uhen 2004, D. atrox was based solely on Andrews holotype skull, lower jaw, and the vertebrae he referred to it,[11] but is now the best-known archaeocete species.[8]

The two species of Dorudon differ from other members of Dorudontinae mainly in size: they are considerably larger than Saghacetus and slightly larger than Zygorhiza, but also differ from both these genera in dental and/or cranial morphology. The limited known material for D. serratus makes it difficult to compare the two species of Dorudon. Uhen 2004 placed D. atrox in the same genus as D. serratus because of similarities in size and morphology, but kept them as separate species because of differences in dental morphology. Even though D. serratus is the type species, the description of Dorudon is largely based on D. atrox because of its completeness. The cranial morphology of D. atrox makes it distinct from all other archaeocetes.[12]

Description

Dorudon was a medium-sized whale, with D. atrox reaching 5 metres (16 ft) in length and 1–2.2 metric tons (1.1–2.4 short tons) in body mass.[13][14] Dorudontines were originally believed to be juvenile individuals of Basilosaurus as their fossils are similar but smaller. They have since been shown to be a different genus with the discovery of Dorudon juveniles. Although they look very much like modern whales, basilosaurines and dorudontines lacked the melon organ that would allow their descendants to use echolocation as effectively as modern whales. Like other basilosaurids, their nostrils were midway from the snout to the top of the head.

Dentition

The dental formula for Dorudon atrox is 3.1.4.23.1.4.3.[15]

Typical for cetaceans, the upper incisors are aligned with the cheek teeth, and, except the small I1, separated by large diastemata containing pits into which the lower incisors fit. The upper incisors are simple conical teeth with a single root, lacking accessory denticles, and difficult to distinguish from lower incisors. The upper incisors are missing in most specimens and are only known from two specimens. The upper canine is a little larger than the upper incisors, and, like them, directed slightly buccally and mesially.[15]

P1, only preserved in a single specimen, is the only single-rooted upper premolar. Apparently, P1 is conical, smaller than the remaining premolars and lacks accessory denticles. P2 is the largest upper tooth and the first in the upper row with large accessory denticles. Like the more posterior premolars, it is buccolingually compressed and double-rooted. It has a dominant central protocone flanked by denticles that decrease in size mesially and distally, resulting in a tooth with a triangular profile. P3 is similar to but slightly smaller than P2, except that it has a projection on the lingual side which is the remnant of a third root. In P4, smaller than P2–3, the larger distal root is formed by the fusion of two roots.[15]

The upper molars extend onto the zygomatic arch and are considerably smaller than their neighbouring premolars. Like P4, their distal root is wider than the mesial and formed by the fusion of two roots. The profiles of the molars are more rounded than those of the premolars.[15]

Similar to the upper incisors, the lower incisors are simple conical teeth curved distally and aligned with the cheek teeth. I1, the smallest tooth, is sitting on the anteriormost portion of the dentary, with its alveolus left open towards the mandibular symphysis and located as close to the alveolus of I2 as it can. I2, I3 and C1 are very similar, considerably larger than I1.[16]

The lower premolars are double-rooted, buccolingually compressed teeth, except the deciduous P1 which is single-rooted. P3 is the second-largest cheek tooth, P4 the largest; both are very similar, dominated by the central cusp.[16]

In the lower molars the accessory denticles on the mesial edges are replaced by a deep groove called the reentrant groove. The apical cusp is the primitive protoconid. M2 and M3 are morphologically very similar. M3 is sitting high on the ascending mandibular ramus.[16]

Paleoecology

Dorudon calves may have fallen prey to hungry Basilosaurus, as shown by unhealed bite marks on the skulls of some juvenile Dorudon.

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 Dorudon in the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved July 2013.

- 1 2 Andrews 1906, p. 255

- ↑ Andrews 1906, p. 243

- ↑ Gibbes 1845, p. 254, Pl. 1

- ↑ Gibbes 1847, pp. 8–11; Agassiz 1848, pp. 4–5

- ↑ Kellogg 1936, pp. 75, 80–81, 86, 89

- 1 2 3 Uhen 2004, Dorudon taxonomy, p. 11

- 1 2 Uhen 2004, Introduction, p. 1

- ↑ Dorudon atrox in the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved July 2013.

- ↑ Dorudon serratus in the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved July 2013.

- ↑ Uhen 2004, p. 17

- ↑ Uhen 2004, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Voss, Manja; Antar, Mohammed Sameh M.; Zalmout, Iyad S.; Gingerich, Philip D. (2019). "Stomach contents of the archaeocete Basilosaurus isis: Apex predator in oceans of the late Eocene". PLOS ONE. 14 (1). e0209021. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1409021V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0209021. PMC 6326415. PMID 30625131.

- ↑ Waugh, D.A.; Thewissen, J.G.M. (2021). "The pattern of brain-size change in the early evolution of cetaceans". PLOS ONE. 16 (9). e0257803. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0257803. PMC 8478358.

- 1 2 3 4 Uhen 2004, pp. 23–29 (upper dentition)

- 1 2 3 Uhen 2004, pp. 29–34 (lower dentition)

Sources

- Agassiz, L. (1848). "Letter from Prof. Agassiz, addressed to Dr. Gibbes, dated Charleston, December 23, 1847". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 5. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- Andrews, C. W. (1906). "A Descriptive Catalogue of the Tertiary Vertebrata of the Fayûm, Egypt". 26. London: British Museum (Natural History): 255–257. OCLC 3675777.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)- "C. W. Andrews 1906". The Paleobiology Database.

- Gibbes, Robert Wilson (1845). "Description of the teeth of a new fossil animal found in the Green Sand of South Carolina". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 2 (9): 254–256.

- "R W Gibbes 1845". The Paleobiology Database.

- Gibbes, Robert Wilson (1847). "On the fossil genus Basilosaurus, Harlan, (Zeuglodon, Owen,) with a notice of specimens from the Eocene Green Sand of South Carolina". Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 1.

- Gingerich, P. D. (1992). "Marine Mammals (Cetacean and Sirenia) from the Eocene of Gebel Mokattam and Fayum, Egypt: Stratigraphy, Age, and Paleoenvironments". University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology. 30: 1–84. hdl:2027.42/48630. OCLC 26941847.

- Haines, Tim & Chambers, Paul. (2006) The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Canada: Firefly Books Ltd.

- Kellogg, Remington (1936). A review of the Archaeoceti (PDF). Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 681376.

- Uhen, Mark D. (2004). "Form, Function, and Anatomy of Dorudon Atrox (Mammalia, Cetacea): An Archaeocete from the Middle to Late Eocene of Egypt". Papers on Paleontology. University of Michigan. 34. hdl:2027.42/41255.