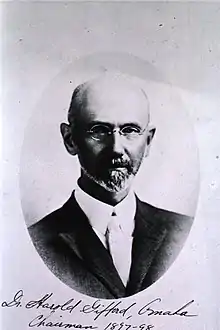

Harold Gifford Sr. (1858-1929) was an ophthalmologist, a discrete philanthropist, and an ardent nature enthusiast. He was born in Milwaukee, WI, obtained his PhD from the University of Michigan, and traveled to Europe for his post-graduate work alongside the most well-respected ophthalmologist of his day. Returning to the United States, Gifford settled in Omaha, NE, where, with his wife Mary at his side, he went on to become one of the city's most prominent surgeons.[1][2]

Career

In 1879, Gifford graduated from Cornell University and went on to become 'Assistant to the Professor of Materia Medica and Ophthalmic and Aural Surgery' at the University of Michigan where he obtained his PhD in ophthalmology in 1882. Shortly thereafter, he continued his post-graduate work, briefly in New York before traveling to Europe. While there, the doctor was appointed First Assistant to one of the forerunners of modern ophthalmology, Johann Friedrich Horner, of Zürich, Switzerland.[3][4]

Gifford moved to Omaha, NE, in 1886, where he became the city's first practicing ophthalmic surgeon. From 1895 to 1898 he was a professor of ophthalmology and dean of the Omaha Medical College, later known as the University of Nebraska Medical Center(UNMC).

After a brief hiatus from teaching he returned to the field as professor of optometry at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine, not to be confused with similarly named UNMC, where he taught between the years 1903–1925. He also served as associate dean of this institution from 1902 to 1911.[5]

During this hiatus, Gifford conducted laboratory research, in some cases volunteering his own eyes as test subjects, during which time he made several discoveries furthering man's understanding of the cause of diseases of the eyes. The results of one such experiment, published in 1896, determined that acute conjunctivitis was caused by a bacterium named pneumococcus.[6]

Life beyond work

When he moved to Omaha in 1886 one of the driving motivations was to secure the hand of Mary Louise Millard, the daughter of Ezra Millard, a prominent banker, and pioneer land developer. Together, he and his wife had four children: Harold Jr. and his brother Sanford, who would both later follow in their father's footsteps, as well as daughters Anne and Mary.[5]

As a devoted naturalist he spent long hours outdoors, sometimes taking walks along the Missouri River, enjoying the country air from the seat of his Stanley Steamer, or a round of golf on his personal nine-hole course built on his farm just north of Omaha. His belief that all men have the right to enjoy nature led him to donate a portion of his farm to the city of Omaha. This land went on to become a large portion of Fontenelle Forest. As well, he gave of the land that later became known as Gifford Park.[1]

His philanthropy didn't stop there. As a man of wealth and prestige he had much to give, and did so without need of recognition. Besides donating to the Red Cross and money for Serbian relief he, along with his wife, gave to numerous charities and civic organizations.

As Sarah Joslyn is quoted to have said after Gifford's death from heart attack in 1929, "He was not only a great doctor, but a great philanthropist. The world will never know what he has done as a philanthropist, because he worked in such a quiet way."[5]

References

- 1 2 "Gifford Park and Its Namesake". Gifford Park History Book. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ Truhlsen, Stanley M. (1999-11-01). "Harold Gifford, Sr., M.D. Omaha's premier turn of the century ophthalmologist". Documenta Ophthalmologica. 99 (3): 237–245. doi:10.1023/A:1002716108976. ISSN 1573-2622. PMID 11108123. S2CID 37889641.

- ↑ "Harold Gifford". Whonamedit.com. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ Donnelly, Walter (1951). The University of Michigan, an Encyclopedic Survey ...: pt. 1. UM Libraries. pp. 846–847.

- 1 2 3 "UNMC History 101: The Oracle of Omaha Ophthalmology". University of Nebraska Medical Center. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ↑ Gifford M.D, S. R. (1930). "Some Practical Procedures Used by Dr. Harold Gifford". Archives of Ophthalmology. 4: 1–15. doi:10.1001/archopht.1930.00810090009001. Retrieved 11 November 2014.