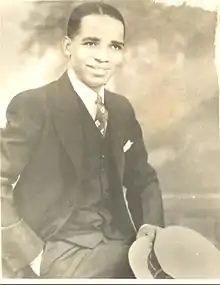

Hastings Kamuzu Banda | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of Malawi | |

| In office 6 July 1966 – 24 May 1994 | |

| Preceded by | Elizabeth II as Queen of Malawi |

| Succeeded by | Bakili Muluzi |

| Prime Minister of Malawi | |

| In office 6 July 1964 – 6 July 1966 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor-General | Sir Glyn Smallwood Jones |

| Preceded by | Post established |

| Succeeded by | Himself as President |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Akim Kamnkhwala Mtunthama Banda c. Spring 1906? Kasungu, British Central Africa (now Kasungu, Malawi) |

| Died | 25 November 1997 (aged 90–91) Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa |

| Political party | Malawi Congress Party |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago Central State University Indiana University Meharry Medical College University of Edinburgh |

| Religion | Presbyterian (Church of Scotland) |

Hastings Kamuzu Banda (1906[1][2][3] – 25 November 1997) was the leader of Malawi from 1964 to 1994. He served as Prime Minister from independence in 1964 to 1966, when Malawi was a Dominion / Commonwealth realm).[4] In 1966, the country became a republic and he became the first president as a result, ruling until his defeat in 1994.

After receiving much of his education in ethnography, linguistics, history, and medicine overseas, Banda returned to Nyasaland to speak against colonialism and advocate independence from the United Kingdom. He was formally appointed Prime Minister of Nyasaland, and led the country to independence in 1964.[5]

Two years later, he proclaimed Malawi a republic with himself as the first president. He consolidated power and later declared Malawi a one-party state under the Malawi Congress Party (MCP). In 1970, the MCP made him the party's President for Life. In 1971, he became president for Life of Malawi itself. A renowned anti-communist leader in Africa, he received support from the Western Bloc during the Cold War.[6] He generally supported women's rights, improved the country's infrastructure and barely maintained a good educational system relative to other African countries.[7] However, he presided over one of the most repressive regimes in Africa, an era that saw political opponents regularly tortured and murdered.[8][9][10] Human rights groups estimate that at least 6,000 people were killed, tortured and jailed without trial.[11] As many as 18,000 people were killed during his rule, according to one estimate.[12][13] His rule has been characterised as a "highly repressive autocracy."[14] He received criticism for maintaining full diplomatic relations with the apartheid government in South Africa.

By 1993, amid increasing domestic and international pressure, he agreed to hold a referendum which ended the one-party system. Soon afterwards, a special assembly ended his life-term presidency and stripped him of most of his powers. Banda ran for president in the democratic elections that followed and was defeated. He died in South Africa on 25 November 1997.

Early life

Kamuzu Banda was born Akim Kamnkhwala Mtunthama Banda near Kasungu in Malawi (then British Central Africa) to Mphonongo Banda and Akupingamnyama Phiri. His date of birth is unknown, as it took place when there was no birth registration documentation, but Banda himself often gave his date of birth as 14 May 1906. Later, when presented with evidence of certain tribal customs by a friend, Dr Donal Brody, Banda said: "No one knows the hour, the date, the month or the year in which I was born, although I now accept the evidence that you give me – March or April 1898."[15]

He left his village school near Mtunthama for his maternal grandparents' home and attended Chayamba Primary School in Chikondwa. In 1908, he moved to Chilanga mission station and was baptised in 1910.[16]

The name Kamnkhwala, meaning "little medicine", was replaced with Kamuzu, which means "little root". The name Kamuzu was given to him because he was conceived after his mother had been given root herbs by a medicine man to cure infertility.[17] He took the Christian name of Hastings after being baptised into the Church of Scotland by Dr George Prentice, a Scot, in 1910, naming himself after John Hastings, a Scottish missionary working near his village whom he admired. The prefix "doctor" was earned through his education.[17]

Around 1915–1916, Banda left home on foot with Hanock Msokera Phiri, an uncle who had been a teacher at the nearby Livingstonia mission school, for Hartley, Southern Rhodesia (now Chegutu, Zimbabwe). He apparently wanted to enroll at the famous Scottish Presbyterian Lovedale Missionary Institute in South Africa but completed his Standard 8 education without studying there. In 1917, he left on foot for Johannesburg in South Africa. He worked at the Witwatersrand Deep Mine on the Transvaal Reef for several years. During this time, he met Bishop William Tecumseh Vernon of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) who offered to pay his tuition fee at a Methodist school in the United States if he could pay his own passage.[17] In 1925, he left for New York.

Life abroad (1925–1958)

United States

Banda studied in the high school section of the Wilberforce Institute, an African American AME college (a member of AME), now known as Central State University, in Wilberforce, Ohio, and graduated in 1928[18] with a diploma. With his financial support now ended, Banda earned some money on speaking engagements arranged by the Ghanaian educationalist Kweyir Aggrey, whom he had met in South Africa.

Speaking at a Kiwanis club meeting he met Dr Herald, with whose help he enrolled as a pre-medical student at Indiana University, where he lodged with Mrs W. N. Culmer. At Bloomington, he wrote several essays about his native Chewa tribe for the folklorist Stith Thompson, who introduced him to Edward Sapir, an anthropologist at the University of Chicago, to which, after four semesters, he transferred. During his period there, he collaborated with the Afro-American anthropologist and linguist Mark Hanna Watkins, providing information on his native Chewa language. This led to the publication of a grammar book of the language.[19] In Chicago, he lodged with an African-American, Corinna Saunders. He majored in history, graduating with a B.Phil. degree in 1931.

During this time he enjoyed financial support from Mrs Smith, whose husband, Douglas Smith, had made fortunes from patent medicines and Pepsodent toothpaste and as a member of the Eastman Kodak board. He then, still with financial support from these and other benefactors (including Walter B. Stephenson of the Delta Electric Company), studied medicine at Meharry Medical College in Tennessee,[20] from which he obtained an M.D. degree in 1937. Banda became the second Malawian person to receive a medical degree, following Daniel Sharpe Malekebu. While studying at Meharry Medical College in Tennessee, Banda married Robertine Edmonds in 1934.[21]

United Kingdom

To practise medicine in territories of the British Empire, however, Banda was apparently required to gain a second medical degree; he attended the University of Edinburgh[18] and was subsequently awarded a Scottish triple conjoint diploma (with post-nominals LRCP(Edin), LRCS(Edin) and LRCPSG) in 1941. His studies were funded by stipends of £300 per year from the government of Nyasaland (to facilitate his return there as a doctor) and from the Church of Scotland; neither of these benefactors was aware of the other. (There are conflicting accounts of this. He might still have been funded by Mrs Smith.) When he enrolled for courses in tropical diseases in Liverpool, the Nyasaland government terminated his stipend. He was forced to leave Liverpool when he refused on conscientious grounds to be conscripted as an Army doctor.[17] He also became an elder of a parish in the Church of Scotland.[17]

Between 1941 and 1945, he worked as a doctor in North Shields, near Newcastle upon Tyne. He was a tenant of Mrs Amy Walton at this time in Alma Place in North Shields and sent a Christmas card to her every year right up until her death in the late-1960s.. In 1944, he met Merene French, the daughter-in-law of one of his patients, and began a relationship with her.[22]

After World War II, he established a practice at the London suburb of Kilburn and became politically active by joining the Labour Party and Fabian Colonial Bureau, which was founded in 1940.[23] Banda moved to London in 1945, buying a practice in the North London suburb of Harlesden. Initially, he stayed at Mrs French's house, with Mr French joining them in October 1945. Later, he bought his own house in Brondesbury Park. Mrs French moved in as his housekeeper, together with her husband. According to other accounts, he lodged in a hotel, The Conway Court, in Paddington run by Mrs Janet Evans. Reportedly, he avoided returning to Nyasaland for fear that his new-found financial resources would be consumed by his extended family back home.

In 1945, at the behest of Chief Mwase of Kasungu, whom he had met in England in 1939, and other politically active Malawians, he represented the Nyasaland African Congress at the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester. This conference was attended by other future African leaders, Jomo Kenyatta and Kwame Nkrumah. [24] With help from sympathetic Britons, he also lobbied in London on behalf of the Congress.

Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland and move to Ghana

Banda was actively opposed to the efforts of Sir Roy Welensky, a politician in Northern Rhodesia, to form a federation between Southern and Northern Rhodesia with Nyasaland, a move which he feared would result in further deprivation of rights for the Nyasaland blacks. The (as he called it) "stupid" federation was formed in 1953.

It was rumoured with some excitement that he would return to Nyasaland in 1951, but he moved instead to the Gold Coast[18] in West Africa. He went there partly because of a scandal involving his receptionist in Harlesden, Merene French (Mrs French); despite reports that she became pregnant with his child, this has never been confirmed. Banda was cited as co-respondent in the divorce of Mr French and accused of adultery with Mrs French. She followed Banda to West Africa, but he wanted nothing more to do with her.[17] (She died in 1976.)[25]

Call to return home

Several influential Congress leaders, including Henry Chipembere, Kanyama Chiume, Dunduzu Chisiza and T.D.T. Banda (no relation) pleaded with him to return to Nyasaland to take up leadership of their cause. A delegation sent to the UK met with Banda at the Port of Liverpool, Liverpool, where he was making arrangements to return to Ghana. He agreed to return, but asked for some time to sort out a few private matters. The delegation returned without him and proceeded to make arrangements for his imminent return. After two false starts, including a fracas between the police and African crowds threatening to storm a BOAC aeroplane rumoured to be carrying Dr Banda at Chileka Airport, Banda finally made a showing on 6 July 1958[20] after an absence of about 42 years. In August, at Nkata Bay, he was acclaimed as the leader of the Congress.

Return to Nyasaland

He soon began touring the country, speaking against the Central African Federation (also known as the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland), and urging its citizens to become members of the party.[26] Allegedly, he was so out of practice in his native Chichewa that he needed an interpreter, a role which was apparently performed by John Msonthi and later by John Tembo, who remained close to him for most of his career).[27] He was received enthusiastically wherever he spoke, and resistance to imperialism among the Malawians became increasingly common. By February 1959, the situation had become serious enough that Rhodesian troops were flown in to help keep order, and a state of emergency was declared. On 3 March, Banda, along with hundreds of other Africans, was arrested in the course of "Operation Sunrise". He was imprisoned in Gwelo (now Gweru) in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe),[28] and leadership of the Malawi Congress Party (the Nyasaland African Congress under a new name) was temporarily assumed by Orton Chirwa, who was released from prison in August 1959.

Release from prison and path to independence

The mood in Britain, meanwhile, had long been moving towards decolonisation due to pressure from its colonies. Banda was released from prison in April 1960 and was almost immediately invited to London for talks aimed at bringing about independence. Elections were held in August 1961. While Banda was technically nominated as Minister of Land, Natural Resources and Local Government, he became de facto Prime Minister of Nyasaland – a title granted to him formally on 1 February 1963. He and his fellow MCP ministers quickly expanded secondary education, reformed the so-called Native Courts, ended certain colonial agricultural tariffs and made other reforms. In December 1962, R. A. Butler, British Secretary of State for African Affairs, essentially agreed to end the Federation.

It was Banda himself who chose the name "Malawi" for the former Nyasaland; he had seen it on an old French map as the name of a "Lake Maravi" in the land of the Bororos, and liked the sound and appearance of the word as "Malawi".[29] On 6 July 1964, exactly six years after Banda's return to the country, Nyasaland gained independence and renamed itself Malawi.

Leader of Malawi

1964 cabinet crisis

Barely a month after independence, Malawi suffered the Cabinet Crisis of 1964. Banda had already been accused of autocratic tendencies. Several of Banda's ministers presented him with proposals designed to limit his powers. Banda responded by dismissing four of the ministers. Other ministers resigned in sympathy.[26] The dissidents fled the country.

New constitution and consolidation of power

.jpg.webp)

Malawi adopted a new constitution on 6 July 1966, in which the country was declared a republic. Banda was elected the country's first president for a five-year term; he was the only candidate. The new document granted Banda wide executive and legislative powers, and also formally made the MCP the only legal party. However, the country had already been a de facto one-party state since independence. The new constitution effectively turned Banda's presidency into a legal dictatorship.

In 1970, a congress of the MCP declared Banda its president for life. In 1971, the legislature declared Banda President for Life of Malawi as well.[26] For the next quarter century, his full title was "His Excellency the Life President of the Republic of Malawi, Ngwazi Dr. H. Kamazu Banda." The title "ngwazi" means "saviour" or "conqueror" in Chichewa.

Banda was mostly viewed externally as a benign, albeit eccentric, leader, an image fostered by his English-style three-piece suits, matching handkerchiefs, walking stick and fly-whisk. In June 1967, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Massachusetts with the encomium " ... pediatrician to his infant nation". However, this image masked a regime that was rigidly authoritarian even by African standards of the time. While the constitution nominally guaranteed all manner of civil liberties, his government paid little attention to them in practice. Banda himself bluntly summed up his approach to ruling the country by saying, "Everything is my business. Everything. Anything I say is law...literally law."[11] Within Malawi, views on him ranged from cult-like devotion to fear.

The Mwanza Four incident

In 1983, three ministers – Dick Matenje, Twaibu Sangala, Aaron Gadama – and Member of Parliament David Chiwanga died in what was labelled officially as a "traffic accident". Banda had invited an "internal debate on pending multiparty democracy" in Malawi. During a cabinet meeting, the three ministers had voiced support for the multiparty idea, effectively challenging Banda's claim to life presidency. Angered, Banda promptly "dissolved cabinet" and announced that parliament would meet immediately. At the end of that sitting of parliament, everyone in the chambers was effectively stripped of their political status. The three men were then rounded up at the Zomba Parliament buildings for questioning. Chiwanga happened on them being tortured in a back room and had to be silenced too. The four were later bundled into Matenje's Peugeot 604 and driven to Thambani in Mwanza District, west of Blantyre, where the accident was staged: sources reported that their car had "overturned while the men had been attempting to escape into neighbouring Mozambique". Later, it was found out they had been killed by having tent pins hammered into their heads.[30] Banda ordered a night burial and mandated that the caskets not be opened for a last viewing.

Foreign policy

Anti-communism

During Banda's presidency, Malawi initially refused to establish diplomatic relations with any of the communist governments of Eastern Europe or Asia[31] (however, relations were later established with North Korea in 1982[32] and with Romania and Albania in 1985).[33]

Banda was one of the few African leaders to support the United States in the Vietnam War, a position he adopted in part due to his hatred of communism.[34]

Relations with African countries

While many southern African nations traded with apartheid-era South Africa out of economic necessity, Malawi was the only African nation that recognised South Africa and established diplomatic relations with it, including a trade treaty which angered other African leaders.[35] They threatened to expel Malawi from the Organization of African Unity until Banda left power.[35] Banda responded by accusing other African countries of hypocrisy, saying in a public speech to his parliament: "There is no terror, Cassius, in your threats" (Julius Caesar).[35] He told them to concentrate on convincing the South African government that apartheid was unnecessary. Furthermore, he added that "[African leaders] practice disunity, not unity, while posing as the liberators of Africa. While they play in the orchestra of Pan Africanism, their own Romes are burning".[35]

Relations with South Africa

Banda was the only African ruler to establish diplomatic ties with South Africa during apartheid as well as the Portuguese regime in Mozambique.[26] After the cabinet crisis in 1964, Banda became increasingly isolated in African politics.[26] On the other hand, his antipathy for Roy Welensky and what he denounced as the "stupid federation"[36] was a smokescreen he used to reject the proposed Bangula Hydro-electric dam – proposed to be bigger than the Gezira Dam in Khartoum – that Welensky's Federation had sought and obtained funding for from the British government. Banda went on to blame everything including snails (likely to cause widespread Bilharzia) to abort the project. In turn, the British denied Banda the funding and budgetary support he needed to build his pet dream of a new capital city at Lilongwe, in his home region. Hence he turned to South Africa – itself playing geo-political games in the region – which gave him a soft loan of 300 million Rand. The quid pro quo was that Banda had to support South Africa's apartheid policies among fellow African leaders. Hence, on one occasion he paid a state visit to South Africa where he met his South African counterparts at Stellenbosch. Banda once noted that, "It is only contact like this [between South Africa and Malawi] that can reveal to your people that there are civilized people other than white..."[37] Banda's staunch anticommunism also influenced his decision to seek warm relations with South Africa.[38]

After the apartheid era ended and the ANC came to dominate South African politics during the 1990s, relations between Malawi and South Africa threatened to take a downward turn, but a Malawian task force spearheaded by Malawian diplomatic envoys to South Africa including SP Kachipande, and representatives in Malawi, including former diplomat, Mr. Phiri, arranged for a meeting between the two governments which resulted in Nelson Mandela's first official visit to Malawi as president of the ANC in the early 1990s. He met with John Tembo and the president. The relations between the two governments continued to be cordial after it was revealed that Banda was secretly helping the ANC during the apartheid era. The Malawi government and South African government continued diplomatic relations.

Involvement in Mozambique

Banda's involvement in Mozambique dated back to Portuguese colonial days in Mozambique when Banda supported the Portuguese colonial government and guerrilla forces that worked for it.[39] Following independence in Malawi, Banda strengthened his relationship with the Portuguese colonial government by appointing Jorge Jardim as Malawi's Honorary Consul in Mozambique in September 1964.[39] He also worked against Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO) forces in Malawi in continued support of the Portuguese colonial forces.[39] The Organization of African Unity had designated Malawi as one of the Frontline States to help independence movements in Mozambique.[39]

By the 1980s, Banda supported both the government and the guerrilla movement during the Mozambique civil war.[39] He successfully gave the Malawi Army and Malawi Young Pioneers opposing missions in Mozambique from 1987 to 1992.[39][40] He had the Malawi Army support the Mozambican government, controlled by FRELIMO after the country's independence in 1975, to defend Malawi's interests in Mozambique. This was done formally through an agreement in 1984 with Samora Machel.[39] Simultaneously, Banda used the MYP as couriers and active supporters of the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO), which had been fighting against Machel's government since the late 1970s.[39] Malawi was used to channel foreign aid from South Africa's apartheid government. Machel issued a dossier to Frontline States with evidence that Banda was still supporting the insurgents in spite of the 1984 agreement to stop.[39] By September 1986, Machel, Robert Mugabe, and Kenneth Kaunda visited Banda to persuade him to stop supporting RENAMO.[39] Machel's successor, Joaquim Chissano, continued to complain of Malawi's lack of willingness to stop supporting RENAMO.[39] Banda however was trying to keep Malawian interests in the Port of Nacala in Mozambique and did not want to rely on Tanzania and South Africa ports for its imports and exports due to the expense.[39] Mozambique and Malawi came to an agreement to place troops from both countries in Nayuchi near the port.[39] Incidents of Malawi Army members being killed over the course of four years angered the Army because MYP members were involved with the insurgents, essentially pitting the two against each other.[39]

Political demise

The end of the Cold War sounded the death knell for Banda's naked autocracy. Western leaders and international aid donors no longer had any use for authoritarian anti-Communist regimes in the Third World, all of which came under mounting pressure to democratize. Donors told Banda that he had to implement reforms aimed at making his government transparent and accountable to the people and the international community as a condition for further aid. The British government also stopped their financial support.[39] In March 1992, Catholic bishops in Malawi issued a Lenten pastoral letter that criticized Banda and his government. Students of the University of Malawi at Chancellor College and the Polytechnic joined protests and demonstrations to support the bishops, forcing authorities to close the campuses.

In April 1992, Chakufwa Chihana, a labour unionist, openly called for a national referendum on the political future of Malawi.[39] He was arrested before he finished his speech at Lilongwe International Airport.[39] By October 1992, this mounting pressure from within and from the international community forced Banda to concede to hold a referendum on whether to maintain the one-party state. The referendum was held on 14 June 1993,[41] resulting in an overwhelming vote (64 percent) in favour of multiparty democracy.[39][42] After this, political parties besides the MCP were formed and preparation for the general elections began. Banda worked with the newly forming parties and the church, and made no protest when a special assembly stripped him of his title of President for Life, along with most of his powers.[39] The transition from one of the most repressive regimes in Africa to democracy was fairly peaceful.[41]

Operation Bwezani was a Malawi Army operation to disarm the Malawi Young Pioneers at the height of the political transition in December 1993. Bwezani means "give back."[41] The MYP had a strong network of spies and supporters countrywide at all levels in society.[39] They were Banda's personal security bodyguards and were all trained and indoctrinated in Kamuzuism and military training.[39] The Malawi Army did not infiltrate this group before receiving encouragement by protests by the people.[39]

After some questions about his health, Banda ran in Malawi's first truly democratic presidential election in 1994. He was roundly defeated by Bakili Muluzi,[26] a Yao from the southern region of the country. Banda quickly conceded defeat. ″I wish to congratulate him wholeheartedly and offer him [Muluzi] my full support and cooperation,″ he said on state radio, marking an end to Malawi's 30 years of one-party rule.[43]

The party Banda led since taking over from Orton Chirwa in 1960, the Malawi Congress Party, remains a major force in Malawian politics.[44]

Mwanza trials

In 1995, Banda was arrested and charged with the murder, ten years previously, of former cabinet colleagues. He was acquitted due to lack of evidence.[26]

Banda remained quite unrepentant in his opinion of Malawians, calling them "children in politics" and saying they would miss his iron-fisted rule.[45]

A statement of apology was issued on 4 January 1996 in the name of H. Kamuzu Banda to the people of his nation shortly after being acquitted in the Mwanza Trials.[46] The statement was met with controversy, suspicion and disdain. It was also questioned whether Banda wrote the statement himself or if someone wrote it on his behalf.[46] In it, he noted that:

Systems of government are dynamic and they are bound to change in accordance with the wishes of and aspirations of the people...During my term of office, I selflessly dedicated myself to the good cause of Mother Malawi in the fight against Poverty, Ignorance and Disease among many other issues; but if within the process, those who worked in my government or through false pretence in my name or indeed unknowingly by me, pain and suffering was caused to anybody in this country in the name of nationhood, I offer my sincere apologies. I also appeal for a spirit of reconciliation and forgiveness amongst us all...Our beautiful country has been nicknamed `The Warm Heart of Africa' and we have been admired for our warmth and spirit of hardwork. This admiration calls not only for a need for us to look at our past and present and draw lessons from it, but there is even a greater need for us to look forward to the future in our endeavours to reconstruct and reconcile if we have to move forward at all.[46]

Life in Banda's Malawi

Party membership passcards

All adult citizens were required to be members of the MCP. Party cards had to be carried at all times and presented at random police inspections. The cards were sold, often by Banda's Malawi Young Pioneers (MYP). In some cases, these youths even sold cards for unborn children.

Malawi Young Pioneers

The Malawi Young Pioneers were the notorious paramilitary wing of the MCP, used to intimidate and harass the public.[41] The Pioneers bore arms, conducted espionage and intelligence operations, and were trusted bodyguards for Banda.[41] They helped foster the culture of fear that prevailed during his rule.[41]

Cult of personality

Banda was the subject of an extensive cult of personality.[20] Every business building was required to have an official picture of him hanging on the wall, and no poster, clock or picture could be higher than his portrait. Before every film, a video of Banda waving to the people was shown while the anthem played. When Banda visited a city, a contingent of women were expected to greet him at the airport and dance for him. A special cloth, bearing the president's picture, was the required attire for these performances. Houses of worship required government approval to operate, and some faiths such as Jehovah's Witnesses were banned entirely.

Censorship

All films shown in cinemas were first viewed by the Malawi Censorship Board and edited for content. Nudity and other socially or politically unacceptable content were barred and movies could not even show couples kissing. Videotapes had to be sent to the Censorship Board to be viewed. Once edited, the film was given a sticker stating that it was now suitable for viewing and sent back to the owner. Items to be sold in bookshops were also edited. Pages, or parts of pages, were cut out of magazines like Newsweek and Time. Communist literature, erotic magazines, and Lonely Planet's Africa on a Shoestring were banned.[47] The mass media–a single radio station, a single daily newspaper, and a single weekly newspaper–were tightly controlled and mainly served as outlets for government propaganda, while the government refused to introduce television.[48] However, wealthier Malawians bought sets as monitors for their VCRs.[49] Knowledge of pre-Banda history was discouraged, and many books on these subjects were burned. Banda allegedly persecuted some of the northern tribes (particularly the Tumbuka), banning their language and books as well as teachers from certain tribes. Foreigners who broke any of these rules were often declared Prohibited Immigrants and deported.[50]

Dress code and conservatism

His government supervised the people's lives very closely. Early in his rule, Banda instituted a dress code rooted in his socially conservative predilections. Women were not allowed to wear see-through clothing, to have visible cleavages, trousers,[20] and were not allowed to wear skirts or dresses that went above the knees. The only exception to this was at vacation resorts and country clubs, where they could not be seen by the general public. Banda explained that these restrictions were not designed to oppress women, but instill respect and dignity for them. Men's hair had to be no longer than collar length, and foreign visitors at the airport were given mandatory haircuts if necessary. Any man who ventured into public with long hair could also be seized by police and subjected to an involuntary haircut.

Even foreigners coming into Malawi were subject to Banda's dress code. In the 1970s, prospective visitors to the country were informed of the following requirement for obtaining visas:

Female passengers will not be permitted to enter the country if wearing short dresses or trouser-suits, except in transit or at Lake Holiday resorts or National parks. Skirts and dresses must cover the knees to conform with Government regulations. The entry of 'hippies' and men with long hair and flared trousers is forbidden.[51]

Women's issues

Banda founded Chitukuko Cha Amai m'Malawi (CCAM) to address the concerns, needs, rights and opportunities for women in Malawi. This institution motivated women to excel in education and government and encouraged them to play more active roles in their community, church and family. The foundation's National Advisor was Cecilia Tamanda Kadzamira, the official hostess for the former president.

Infrastructure

In 1964, after serving as a government minister in the colonial administration, Banda adopted a macroeconomic policy aimed at accelerating economic development for the betterment of Malawians. He settled on the Rostow model of "catch up" economics, wherein Malawi would vigorously pursue import substitution industrialisation (ISI). This entailed both a quest for "self-sufficiency" for Malawi – becoming less reliant on its former colonial master – and growth of an industrial base that could ensure Malawi was capable of producing its own goods and services. Such capacity would then be used to catch up and even overtake the West. An infrastructure development program was initiated under the Development Policies (DEVPOLs) documents that Malawi adopted from 1964 onwards. Much of this development was funded through the Agricultural Development and Marketing Corporation, a Government-owned corporation or parastatal formed to promote the Malawian economy by increasing the volume of agricultural exports and to develop new foreign markets for Malawian agricultural produce. At its foundation, ADMARC was given the power to finance the economic development of any public or private organisation. From its formation it was involved in the diversion of resources from smallholder farming to tobacco estates, often owned by members of the ruling elite. This led to corruption, abuse of office and inefficiency in ADMARC,

The country's infrastructure benefited through massive road construction programs. With the decision to shift the capital city from Zomba to Lilongwe (against vociferous objections from the British preference for the economically healthy and well-developed Blantyre), a new road was built linking Blantyre and Zomba to Lilongwe. The Capital City Development Corporation (CCDC) in Lilongwe was itself a beehive of infrastructure development, supported by planning and funds from apartheid-era South Africa. The British refused to finance the move to Lilongwe. The CCDC became the sole development agent for Lilongwe; putting up roads, the government seat at Capital Hill, etc. Other infrastructure entities were added, such as Malawi Hotels Limited, which undertook massive projects such as the Mount Soche, Capital Hotel and Mzuzu Hotel. On the industrial side, Malawi Development Corporation (MDC) was tasked with setting up industries and other businesses. Meanwhile, Dr. Banda's own Press Corporation Limited and MYP's Spearhead Corporation embarked on business initiatives that lead to an economic boom during the mid- to late 1970s.

However, by 1979–1980, the bubble had burst due to the global economic crisis set in motion by the Yom Kippur War between Israel and the Arabs in 1973. Rising oil prices and falling global commodity prices combined to wreak havoc on a fragile and landlocked Malawian economy based on an insular and indefensible ISI macroeconomic strategy. Increasingly, the economy was rearranged into a political tool to serve the consumption needs of the emerging Malawian middle-class and thus render it less prone to revolution.

Banda personally founded Kamuzu Academy, a school modeled on Eton, at which Malawian children were taught Latin and Greek by expatriate classics teachers, and disciplined if they were caught speaking Chichewa.[52] Many of the school's alumni have assumed leadership roles in medicine, academia and business in Malawi and abroad. The school remains one of Banda's most lasting legacies and he said of it: "I did not wish my sons and daughters to have to travel abroad to obtain an education as I did." It is claimed, probably incorrectly and unfairly, that he spent almost all the country's education budget on this project,[53] while increasingly ignoring the needs and welfare of the greater majority [80%] of Malawians toiling in the rural areas. The National Rural Development Program and Rural Growth Centers were tentative and belated policies aimed at diverting rural populations from moving to the few urban areas which Banda's ISI macroeconomic policies had created and were now being battered by the arrival of more and more rural people seeking better opportunities.

Eventually, with the collapse of the Cold War, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund arrived, imposing a series of Structural Adjustment Programs[54] from 1987.

Wealth

It is believed that during his rule, Banda accumulated at least US$320 million in personal assets,[55] thought to be invested in everything from agriculture to mining interests in South Africa.

Personal life

Banda had no known heirs but had a vast fortune that is run by his family.[55] He was unmarried when he died. Cecilia Kadzamira was the official hostess or first lady of Malawi.[55] She essentially ruled the country with her uncle, John Tembo, during Banda's last years.

His affair and relationship with Merene French remains largely a mystery. He had rejected companionship and marriage and turned his back on the Englishwoman who extramaritally bore his son.[17][56] In 2010, Jumani Johansson (1973–2019) claimed to be the son of the late president and was seeking DNA testing through the courts of Malawi.[57] Grand niece Jane Dzanjalimodzi was the former executrix of his estate.[57]

Death

Banda died at the Garden City Clinic[58] in Johannesburg, South Africa on 25 November 1997, from respiratory failure. Although the clinic recorded his age as 99, Government officials state it was more likely he was aged around 90.[55][59] Although he was buried with pomp, in the decade after his death there were calls for a more substantial memorial for the country's first president. Construction of a mausoleum with provision for a library and a dancing arena was begun in 2005.[60] Completed in 2009 - at a cost of US$600,000 - the mausoleum is made out of marble and granite. Its four main pillars bear the initials of Banda's key principles – unity, loyalty, obedience and discipline.[61] In 2009 a bronze statue of Banda was erected.[9] From 10 April 1995, when former Prime Minister of India Morarji Desai died, Banda was the world's oldest living former head of government until his own death in 1997.

See also

- President of Malawi

- Similar protests under his rule:

- 1992–1993 Malawian protests that led to his departure in 1994

References

- ↑ Simfukwe, Meekness (14 May 2015). "Family, nation celebrate Kamuzu's life". The Nation Online.

- ↑ "Obituary: Dr Hastings Banda". The Independent. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ↑ Chauwa, Alfred (5 December 2016). "MCP, family celebrate Kamuzu's life: Chakwera to champion for rebuilding of party headquarters". Nyasa Times.

- ↑ "Hastings Kamuzu Banda - National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ↑ Louis Ea Moyston (16 October 2010). "Howell: man of heroic proportions". Jamaica Observer. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Kalinga, Owen J. M. (2012). Historical Dictionary of Malawi, Fourth Edition, p. 12

- ↑ Rotberg, Robert I. (19 January 2023). "The Hijacking of Malawi: Banda's Uptight Despotism". doi:10.1093/oso/9780197674208.003.0004.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Hastings Kamuzu Banda | president of Malawi". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- 1 2 York, Geoffrey (20 May 2009). "The cult of Hastings Banda takes hold". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ↑ Mccracken, John (1 April 1998). "Democracy and Nationalism in Historical Perspective: The Case of Malawi". African Affairs. 97 (387): 231–249. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007927. Retrieved 23 May 2019 – via academic.oup.com.

- 1 2 Drogin, Bob (21 May 1995). "Malawi Tries Ex-Dictator in Murder : Africa: Aging autocrat is one of few among continent's tyrants to face justice for regime's abuses". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Denver Rocky Mountain News, 17 May 1994.

- ↑ Dallas Morning News, 3 December 1997.

- ↑ Geddes, Barbara; Wright, Joseph; Frantz, Erica (2018). How Dictatorships Work. Cambridge University Press. p. 70. doi:10.1017/9781316336182. ISBN 978-1-316-33618-2. S2CID 226899229.

- ↑ Brody, Donal (2000). "Conversations with Kamuzu: The Life and Times of Dr. H. Kamuzu Banda".

- ↑ M. Kalinga, Owen J. (2012). Historical Dictionary of Malawi. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780810859616.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dowden, Richard (27 November 1997). "Obituary: Dr Hastings Banda". The Independent. London.

- 1 2 3 "Man in the News; Cosmopolitan Malawian; Hastings Kamuzu Banda". The New York Times. 9 September 1964.

- ↑ Watkins, Mark Hanna (1937). "A Grammar of Chichewa: A Bantu Language of British Central Africa". Language. 13 (2): 5–158. doi:10.2307/522167. JSTOR 522167.

- 1 2 3 4 "A CLASSIC DICTATOR". Independent.co.uk. 8 October 1995. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022.

- ↑ Mbughuni, Azariah (8 October 2023). "Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda Married Robertine Edmonds in the United States in 1934". United Africa.

- ↑ Weindling, Dick; Marianne Colloms (21 January 2019). "Hastings Banda and his English Mistress". History of Kilburn and West Hampstead.

- ↑ "Commonwealth and African Studies Bodleian Library". Bodleian Library, Oxford University.

- ↑ Adi, Hakim; Sherwood, Marika (1995). The 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress Revisited. New Beacon Books. ISBN 978-1-873201-12-1.

- ↑ Kalinga, Owen (16 January 2012). Historical Dictionary of Malawi (4th ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0810859616.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "History of Malawi". Historyworld.net. 31 December 1963. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ Kamuzu Banda of Malawi: A Study in Promise, Power, and Paralysis (Malawi Under Dr Banda) (1961 to 1993), John Lloyd Lwanda, Dudu Nsomba Publications, 1993, page 278

- ↑ Attorney General v Malawi Congress Party & Ors. (Civil Appeal 22 of 1996) [1997] MWSC 1 (30 January 1997)

- ↑ New encyclopedia of Africa - Volume 1 - Page 215, New encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1, John Middleton, Joseph Calder Miller, Thomson/Gale, 2008, page 215

- ↑ Shaw 2005, 8 & Mwanza Road Incident Report (Limbe, Malawi, 1994)

- ↑ Nelson, Harold D., Margarita Dobert, Gordon C. McDonald, James McLaughlin, Barbara Marvin, and Donald P. Whitaker (1975). Area Handbook for Malawi, p. 176.

- ↑ "Malawi – North Korea Relations" Archived 15 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Republic of Malawi. Accessed on 18 January 2020

- ↑ Kalinga, Owen J. M. (2012). Historical Dictionary of Malawi, Fourth Edition, p. xxv.

- ↑ Nelson, Dobert, McDonald, McLaughlin, Marvin, and Whitaker (1975). Area Handbook for Malawi, p. 188.

- 1 2 3 4 "Malawi: Heroes or Neros?". Time. 14 April 1967. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008.

- ↑ Black World/Negro Digest, January 1965, p. 31.

- ↑ "Hasting Banda". Sunday Times. Johannesburg. 24 May 1970. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Nelson, Dobert, McDonald, McLaughlin, Marvin, and Whitaker (1975). Area Handbook for Malawi, p. 178.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 "Afrikka" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ Robinson, David. 2009. “Defense, Ideology or Ambition: An Assessment of Malawian Motivations for Intervention in the Mozambican Civil War” Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences, Vol 1, No 2, 302-322, at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26610131_Defense_Ideology_or_Ambition_An_Assessment_of_Malawian_Motivations_for_Intervention_in_the_Mozambican_Civil_War/fulltext/0ffc56310cf29a969e9c7cba/Defense-Ideology-or-Ambition-An-Assessment-of-Malawian-Motivations-for-Intervention-in-the-Mozambican-Civil-War.pdf.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Operation Bwezani". Kamuzubanda.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ Malawi: 1993 Referendum results Archived 6 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine EISA.

- ↑ Venta, Sahm. "Banda Concedes Defeat; Muluzi Headed for Victory". AP News. Associated Press. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ↑ "Malawi Opposition Parties Form Alliance Ahead of Fresh Polls". Voanews. 12 March 2020.

- ↑ Russell, Alec (1999). Big men, little people : encounters in Africa. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-75359-3. OCLC 41309130.

- 1 2 3 "Democracy in Malawi: Ex-Pres. Banda's Apology". H-net.org. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ Geoff Crowther, Africa on a Shoestring, 5th Edition. Lonely Planet Publications. 1989.

- ↑ Suffering in silence: Malawi women's 30 year dance with Dr Banda, Emily Lilly Mkamanga, Dudu Nsomba Publications, 2000, page 278

- ↑ Blantyre Journal: Malawi Deprived? Well, TV's on Way, New York Times, 30 May 1996

- ↑ The Society of Malawi Journal, Volumes 55–58, 2002, p. 30.

- ↑ Africa on the cheap, 1982, page 179

- ↑ Education, Democracy, and Political Development in Africa, Clive Harber, Sussex Academic Press, 1997, page 9

- ↑ Shaw 2005, 37.

- ↑ Chagunda, Chance (4 February 2021). "Development Aid, Democracy and Sustainable Development in Malawi - 1964 to date". Cadernos de Estudos Africanos (41): 145–164. doi:10.4000/cea.6446.

- 1 2 3 4 Tenthani, Raphael (2000) "Mystery of the Banda millions" BBC News 17 May 2000

- ↑ "Hastings Banda | The Economist". The Economist. 27 November 1997.

- 1 2 "Kamuzu's grand-niece quits Jumani case". Nationmw.net. 17 December 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ M. Kalinga, Owen J. (2012). Historical Dictionary of Malawi. Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxvi. ISBN 9780810859616.

- ↑ McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (27 November 1997). "Kamuzu Banda Dies; 'Big Man' Among Anticolonialists". The New York Times.

- ↑ Sumbuleta, Aubrey (2005), "New tomb for Malawi's Banda", BBC News, 13 May 2005,

- ↑ "Kamuzu Mausoleum | Lilongwe, Malawi Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

Bibliography

- "Banda, Hastings Kamuzu". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004 ed.).

- Hulec, Otakar and Jaroslav Olša, Jr. (2008). Dějiny Zimbabwe, Zambie a Malawi (in Czech, translation of title: History of Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi), Nakladatelství Lidové noviny.

- Lwanda, John Lloyd, (1993). Kamuzu Banda of Malawi: A Study in Promise, Power, and Paralysis, Dudu Nsomba Publications.

- Meredith, Martin (2005). The Fate of Africa: From the Hopes of Freedom to the Heart of Despair, Public Affairs.

- Mgawi, KJ (2005). Tracing the Footsteps of Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda. Dzuka Publications, Blantyre.

- Muluzi, Bakili (with Yusuf M. Juwayeyi, Mercy Makhambera, Desmond D. Phiri), (1999). Democracy with a Price: The History of Malawi since 1900. Jhango Heinemann, Blantyre.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey, (2006). Africa After Independence: Realities of Nationhood. Johannesburg, South Africa: Continental Press.

- Ross, Andrew C. (2009). Colonialism to cabinet crisis: a political history of Malawi, African Books Collective, 2009 ISBN 99908-87-75-6. This gives extensive biographical detail on Hastings Banda.

- Rotberg, Robert I, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Shaw, Karl (2005) [2004]. Power Mad! [Šílenství mocných] (in Czech). Praha: Metafora. ISBN 978-80-7359-002-4.

- Short, Philip (1974). BANDA. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 9780710076311.

- van Donge, Jan Kees (1995). Kamuzu's legacy: the democratisation of Malawi. African Affairs, Vol 94, No 375.

- Williams, T. David (1978). Malawi, the Politics of Despair. Cornell University Press.