| Dragon Boat Festival | |

|---|---|

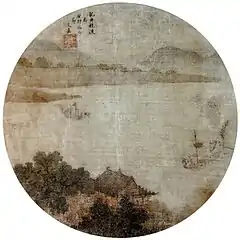

Dragon Boat Festival (18th century) | |

| Observed by | Chinese |

| Type | Cultural |

| Observances | Dragon boat racing, consumption of realgar wine and zongzi |

| Date | Fifth day of the fifth lunar month |

| 2023 date | 22 June |

| 2024 date | 10 June |

| 2025 date | 31 May |

| 2026 date | 19 June |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Tango no sekku, Dano, Tết Đoan Ngọ, Yukka Nu Hii |

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 端午节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 端午節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "The very mid point of the year Festival" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dragon Boat Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 龙船节 / 龙舟节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 龍船節 / 龍舟節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Double Fifth Festival Fifth Month Festival Fifth Day Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 重五节 / 双五节 五月节 五日节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 重五節 / 雙五節 五月節 五日節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dumpling Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 肉粽节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 肉糭節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Meat Zongzi Festival | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese | Festividade do Barco-Dragão | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Dragon Boat Festival (traditional Chinese: 端午節; simplified Chinese: 端午节; pinyin: Duānwǔ Jié) is a traditional Chinese holiday which occurs on the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese calendar, which corresponds to late May or June in the Gregorian calendar.

A commemoration of the ancient poet Qu Yuan, the holiday is celebrated by holding dragon boat races and eating sticky rice dumplings called zongzi. The Dragon Boat Festival is a folk festival integrating worship of gods and ancestors, praying for good luck and warding off evil spirits, celebrating, entertainment and eating.

In September 2009, UNESCO officially approved its inclusion in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, becoming the first Chinese holiday to be selected.[1][2]

Names

The English language name for the holiday is Dragon Boat Festival,[3] used as the official English translation of the holiday by the People's Republic of China.[4] It is also referred to in some English sources as Double Fifth Festival which alludes to the day on which the festival is celebrated, according to the Chinese calendar.[5]

Chinese names by region

The Chinese name of the festival (simplified Chinese: 端午节; traditional Chinese: 端午節) is pronounced differently in different Chinese languages.

The Mandarin Chinese pronunciation used in Mainland China and Taiwan is rendered in pinyin as Duānwǔjié (Wade–Giles: Tuan1-wu3-chieh2).[6][7][8]

Duanwu (Chinese: 端午; pinyin: duānwǔ; Wade–Giles: tuan2-wu3) literally means "starting/opening horse", i.e., the first "horse day" (according to the Chinese zodiac/Chinese calendar system) to occur in the month;[9][lower-alpha 1] however, despite the literal meaning being wǔ, "the [day of the] horse in the animal cycle", this character has also become associated with wǔ (Chinese: 五; pinyin: wǔ; Wade–Giles: wu3) meaning "five", due to the characters often having the same pronunciation. Hence Duanwu, the festival on "the fifth day of the fifth month".[11]

In Cantonese, it is romanized as Tuen1 Ng5 Jit3 in Hong Kong and Tung1 Ng5 Jit3 in Macau. Hence the "Tuen Ng Festival" in Hong Kong,[12] and Tun Ng (Festividade do Barco-Dragão in Portuguese) in Macao.[13][14][15]

History

Origin

The fifth lunar month is considered an unlucky and poisonous month, and the fifth day of the fifth month especially so.[16][17] To get rid of the misfortune, people would put calamus, Artemisia, and garlic above the doors on the fifth day of the fifth month.[16][17] These were believed to help ward off evil by their strong smell and their shape (for instance, calamus leaves are shaped like swords).[17]

Venomous animals were said to appear starting from the fifth day of the fifth month, such as snakes, centipedes, and scorpions; people also supposedly get sick easily after this day.[17] Therefore, during the Dragon Boat Festival, people try to avoid this bad luck.[17] For example, people may put pictures of the five venomous creatures (snake, centipede, scorpion, lizard, toad, and sometimes spider[17]) on the wall and stick needles in them. People may also make paper cutouts of the five creatures and wrap them around the wrists of their children.[18] Big ceremonies and performances developed from these practices in many areas, making the Dragon Boat Festival a day for getting rid of disease and bad luck.

Qu Yuan

The story best known in modern China holds that the festival commemorates the death of the poet and minister Qu Yuan (c. 340–278 BC) of the ancient state of Chu during the Warring States period of the Zhou dynasty.[19] A cadet member of the Chu royal house, Qu served in high offices. However, when the king decided to ally with the increasingly powerful state of Qin, Qu was banished for opposing the alliance and even accused of treason.[19] During his exile, Qu Yuan wrote a great deal of poetry. Eventually, Qin captured Ying, the Chu capital. In despair, Qu Yuan committed suicide by drowning himself in the Miluo River.[16]

It is said that the local people, who admired him, raced out in their boats to save him, or at least retrieve his body.[16][17] This is said to have been the origin of dragon boat races.[17] When his body could not be found, they dropped balls of sticky rice into the river so that the fish would eat them instead of Qu Yuan's body. This is said to be the origin of zongzi.[19]

During the twentieth century, Qu Yuan became considered a patriotic poet and a symbol of the people. He was promoted as a folk hero and a symbol of Chinese nationalism in the People's Republic of China after the 1949 Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War. The historian and writer Guo Moruo was influential in shaping this view of Qu.[20]

Wu Zixu

Another origin story says that the festival commemorates Wu Zixu (died 484 BC), a statesman of the Kingdom of Wu.[16] Xi Shi, a beautiful woman sent by King Goujian of the state of Yue, was much loved by King Fuchai of Wu. Wu Zixu, seeing the dangerous plot of Goujian, warned Fuchai, who became angry at this remark. Wu Zixu was forced to commit suicide by Fuchai, with his body thrown into the river on the fifth day of the fifth month. After his death, in places such as Suzhou, Wu Zixu is remembered during the Dragon Boat Festival.

Cao E

Although Wu Zixu is commemorated in southeast Jiangsu and Qu Yuan elsewhere in China, much of Northeastern Zhejiang, including the cities of Shaoxing, Ningbo and Zhoushan, celebrates the memory of the young girl Cao E (曹娥; AD 130–144) instead. Cao E's father Cao Xu (曹盱) was a shaman who presided over local ceremonies at Shangyu. In 143, while presiding over a ceremony commemorating Wu Zixu during the Dragon Boat Festival, Cao Xu accidentally fell into the Shun River. Cao E, in an act of filial piety, searched the river for 3 days trying to find him. After five days, she and her father were both found dead in the river from drowning. Eight years later, in 151, a temple was built in Shangyu dedicated to the memory of Cao E and her sacrifice. The Shun River was renamed Cao'e River in her honor.[21]

Cao E is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu (無雙譜; Table of Peerless Heroes) by Jin Guliang.

Pre-existing holiday

Some modern research suggests that the stories of Qu Yuan or Wu Zixu were superimposed onto a pre-existing holiday tradition. The promotion of these stories might have been encouraged by Confucian scholars, seeking to legitimize and strengthen their influence in China. The relationship between zongzi, Qu Yuan and the festival first appeared during the early Han dynasty.[22]

The stories of both Qu Yuan and Wu Zixu were recorded in Sima Qian's Shiji, completed 187 and 393 years after the respective events, because historians wanted to praise both characters.

According to historians, the holiday originated as a celebration of agriculture, fertility, and rice growing in southern China.[17][23][24] As recently as 1952 the American sociologist Wolfram Eberhard wrote that it was more widely celebrated in southern China than in the north.[23]

Another theory is that the Dragon Boat Festival originated from dragon worship.[17] This theory was advanced by Wen Yiduo. Support is drawn from two key traditions of the festival: the tradition of dragon boat racing and zongzi. The food may have originally represented an offering to the dragon king, while dragon boat racing naturally reflects a reverence for the dragon and the active yang energy associated with it. This was merged with the tradition of visiting friends and family on boats.

Another suggestion is that the festival celebrates a widespread feature of east Asian agrarian societies: the harvest of winter wheat. Offerings were regularly made to deities and spirits at such times: in the ancient Yue, dragon kings; in the ancient Chu, Qu Yuan; in the ancient Wu, Wu Zixu (as a river god); in ancient Korea, mountain gods (see Dano). As interactions between different regions increased, these similar festivals eventually merged into one holiday.

Early 20th century

In the early 20th Century the Dragon Boat Festival was observed from the first to the fifth days of the fifth month, and was also known as the Festival of Five Poisonous/Venomous Insects (simplified Chinese: 毒虫节; traditional Chinese: 毒蟲節; pinyin: Dúchóng jié; Wade–Giles: Tu2-chʻung2-chieh2). Yu Der Ling writes in chapter 11 of her 1911 memoir Two Years in the Forbidden City:

The first day of the fifth moon was a busy day for us all, as from the first to the fifth of the fifth moon was the festival of five poisonous insects, which I will explain later—also called the Dragon Boat Festival. ... Now about this Feast. It is also called the Dragon Boat Feast. The fifth of the fifth moon at noon was the most poisonous hour for the poisonous insects, and reptiles such as frogs, lizards, snakes, hide in the mud, for that hour they are paralyzed. Some medical men search for them at that hour and place them in jars, and when they are dried, sometimes use them as medicine. Her Majesty told me this, so that day I went all over everywhere and dug into the ground, but found nothing.[25]

21st century

In 2008 the Dragon Boat Festival was made a national public holiday in China.[26]

Public holiday

The festival was long marked as a cultural festival in China and is a public holiday in China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and Taiwan. The People's Republic of China government established in 1949 did not initially recognize the Dragon Boat Festival as a public holiday but reintroduced it in 2008 alongside two other festivals in a bid to boost traditional culture.[27][28]

The Dragon Boat Festival is unofficially observed by the Chinese communities of Southeast Asia, including Singapore and Malaysia. Equivalent and related official festivals include the Korean Dano,[29] Japanese Tango no sekku,[30] and Vietnamese Tết Đoan Ngọ.[30]

Practices and activities

Three of the most widespread activities conducted during the Dragon Boat Festival are eating (and preparing) zongzi, drinking realgar wine, and racing dragon boats.[31]

Dragon boat racing

Dragon boat racing has a rich history of ancient ceremonial and ritualistic traditions, which originated in southern central China more than 2500 years ago. The legend starts with the story of Qu Yuan, who was a minister in one of the Warring State governments, Chu.[16] He was slandered by jealous government officials and banished by the king.[16] Out of disappointment in the Chu monarch, he drowned himself in the Miluo River.[16] The common people rushed to the water and tried to recover his body, but they failed.[16] In commemoration of Qu Yuan, people hold dragon boat races yearly on the day of his death according to the legend.[16][17] They also scattered rice into the water to feed the fish, to prevent them from eating Qu Yuan's body, which is one of the origins of zongzi.[16][17]

Zongzi (traditional Chinese rice dumpling)

A notable part of celebrating the Dragon Boat Festival is making and eating zongzi, also known as sticky rice dumplings, with family members and friends. People traditionally make zongzi by wrapping glutinous rice and fillings in leaves of reed or bamboo, forming a pyramid shape.[16] The leaves also give a special aroma and flavor to the sticky rice and fillings. Choices of fillings vary depending on regions.[16] Northern regions in China prefer sweet or dessert-styled zongzi, with bean paste,[17] jujube,[16] and nuts as fillings. Southern regions in China prefer savory zongzi, with a variety of fillings including eggs and meat.[16][17]

Zongzi appeared before the Spring and Autumn Period and was originally used to worship ancestors and gods. In the Jin Dynasty, zongzi dumplings were officially designated as the Dragon Boat Festival food. At this time, in addition to glutinous rice, the Chinese medicine Yizhiren was added to the ingredients for making zonghzi. The cooked zongzi is called "yizhi zong".[32]

Food related to 5

'Wu' (午) in the name 'Duanwu' has a pronunciation similar to that of the number 5 in multiple Chinese dialects, and thus many regions have traditions of eating food that is related to the number 5. For example, the Guangdong and Hong Kong regions have the tradition of having congee made from 5 different beans.

Realgar wine

Realgar wine or Xionghuang wine is a Chinese alcoholic drink that is made from Chinese liquor dosed with powdered realgar, a yellow-orange arsenic sulfide mineral.[16] It was traditionally used as a pesticide, and as a common antidote against disease and venom.[16][24] On the Dragon Boat Festival, people may put realgar wine on parts of children's faces to repel the five poisonous creatures.[33]

5-colored silk-threaded braid

In some regions of China, people, especially children, wear silk ribbons or threads of 5 colors (blue, red, yellow, white, and black, representing the five elements) on the day of the Dragon Boat Festival.[17] People believe that this will help keep evil away.[17]

Other common activities include hanging up icons of Zhong Kui (a mythic guardian figure), hanging mugwort and calamus, taking long walks, and wearing perfumed medicine bags.[34][16] Other traditional activities include a game of making an egg stand at noon (this "game" implies that if someone succeeds in making the egg stand at exactly 12:00 noon, that person will receive luck for the next year), and writing spells. All of these activities, together with the drinking of realgar wine or water, were regarded by the ancients (and some today) as effective in preventing disease or evil while promoting health and well-being.

In the early years of the Republic of China, Duanwu was celebrated as the "Poets' Day" due to Qu Yuan's status as China's first known poet. The Taiwanese also sometimes conflate the spring practice of egg-balancing with Duanwu.[35]

The sun is considered to be at its strongest around the time of the summer solstice, as the daylight in the northern hemisphere is the longest. The sun, like the Chinese dragon, traditionally represents masculine energy, whereas the moon, like the phoenix, traditionally represents feminine energy. The summer solstice is considered the annual peak of male energy while the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, represents the annual peak of feminine energy. The masculine image of the dragon has thus become associated with the Dragon Boat Festival.[36]

Gallery

Hari in Tomigusuku, Okinawa, Japan.

Hari in Tomigusuku, Okinawa, Japan. Activities to avoid bad luck

Activities to avoid bad luck A bodice worn by kids with symbols of the Five Poisonous Insects on it to deter poisonous insects, and reptiles such as frogs, lizards, snakes.

A bodice worn by kids with symbols of the Five Poisonous Insects on it to deter poisonous insects, and reptiles such as frogs, lizards, snakes. A dragon boat racing in San Francisco, 2008.

A dragon boat racing in San Francisco, 2008. Raw Rice Dumpling

Raw Rice Dumpling Egg balancing in Tangerang, Indonesia

Egg balancing in Tangerang, Indonesia ROC (Taiwan) President Ma Ying-jeou visits Liang Island before Dragon Boat Festival (2010)

ROC (Taiwan) President Ma Ying-jeou visits Liang Island before Dragon Boat Festival (2010)

'恭祝總統端節愉快'

('Respectfully Wishing the President a Joyous Dragon Boat Festival')

See also

Explanatory notes

References

Citations

- ↑ "Dragon Boat festival - UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage". UNESCO. September 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ↑ "端午节:中国首个入选世界非遗的节日". Weixin Official Accounts Platform. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ↑ Chittick (2011), p. 1.

- ↑ Chinese Government's Official Web Portal. "Holidays Archived May 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine". 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ "Double Fifth (Dragon Boat) Festival Archived May 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine".

- ↑ General Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China. 《国务院办公厅关于2011年部分节假日安排的通知国办发明电〔2010〕40号》. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Chinese)

- 1 2 "Dragon Boat Festival". Taiwan Today. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). 1 June 1967.

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). "Holidays and Festivals in Taiwan Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine Archived 2014-02-16 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Chinese and English).

- ↑ Inahata, Kōichirō [in Japanese] (2007). Tango 端午 (たんご). 世界大百科事典 (revised, new ed.). Heibonsha.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) via Japanknowledge. - ↑ Lowe (1983), p. 141.

- ↑ Chen, Sanping (January–March 2016). "Were 'Ugly Slaves' in Medieval China Really Ugly?". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 136 (1): 30–31. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.1.117. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.1.117.

- ↑ GovHK. " General holidays for 2014". 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Macau Government Tourist Office. "Calendar of Events". 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Special Administrative Region of Macao. Office of the Chief Executive. "Ordem Executiva n.º 60/2000". 3 October 2000. Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Portuguese)

- ↑ Special Administrative Region of Macao. Office of the Chief Executive. 《第60/2000號行政命令》. 3 October 2000. Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Chinese)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Wei, Liming (2010). Chinese Festivals: Traditions, Customs and Rituals (Second ed.). Beijing. pp. 36–43. ISBN 9787508516936.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Stepanchuk, Carol (1991). Mooncakes and Hungry Ghosts: Festivals of China. San Francisco: China Books & Periodicals. pp. 41–50. ISBN 0-8351-2481-9.

- ↑ Liu, L. (2011). 'Beijing Review' Color Photographs. vol. 54, issue 23. pp. 42–43.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 SCMP." Earthquake and floods make for the muted festival. Retrieved on 9 June 2008. Archived 25 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Zikpi, Monica E M (2014). "Revolution and Continuity in Guo Moruo's Representations of Qu Yuan". Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR). 36: 175–200. ISSN 0161-9705. JSTOR 43490204. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ↑ "The river in which she jumped was renamed as Cao's River". Archived from the original on 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "The Legends Behind the Dragon Boat Festival". Smithsonian. 14 May 2009.

- 1 2 Eberhard, Wolfram (1952). "The dragon-boat festival". Chinese Festivals. New York: H. Wolff. pp. 69–96.

- 1 2 "Dragon Boat Festival activities expanded". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ↑ Yü, Der Ling (1911). Two Years in the Forbidden City. T. F. Unwin. Project Gutenberg

- ↑ "Dragon Boat Festival keeps the beast at bay". www.chinadaily.com.cn. 14 June 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ↑ People's Daily. "Peopledaily." China to revive traditional festivals to boost traditional culture. Retrieved on 9 June 2008.

- ↑ Xinhua Net. "First day-off for China's Dragon Boat Festival helps revive tradition Archived 2013-12-22 at the Wayback Machine." Xinhua News Agency. Published 8 June 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ↑ "Duanwu: The Sino-Korean Dragon Boat Races". China Heritage Quarterly. September 2007.

- 1 2 Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric et al (2005). "Tango no Sekku" in Japan Encyclopedia, pp. 948., p. 948, at Google Books

- ↑ "Dragon Boat Festival". China Internet Information Center. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Yuan, He (2015). "Textual Research on the Origin of Zongzi". Journal of Nanning Polytechnic.

- ↑ Huang, Shaorong (December 1991). "Chinese Traditional Festivals". The Journal of Popular Culture. 25 (3): 163–180. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1991.1633111.x. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ↑ "Dragon Boat Festival keeps the beast at bay". chinadailyhk.

- ↑ Huang, Ottavia. Hmmm, This Is What I Think: "Dragon Boat Festival: Time to Balance an Egg". 24 June 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Chan, Arlene & al. Paddles Up! Dragon Boat Racing in Canada, p. 27. Dundurn Press Ltd., 2009. ISBN 978-1-55488-395-0. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

Bibliography

- Chittick, Andrew (2011). "The Song Navy and the Invention of Dragon Boat Racing". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 2011 (41): 1–28. doi:10.1353/sys.2011.0025. JSTOR 23496206. S2CID 162282148.

- Lowe, H. Y. (aka Lü Hsing-yüan 慮興源) (2014) [1983]. "The Dragon Boat Festival". The Adventures of Wu: The Life Cycle of a Peking Man. Translated by Bodde, Derk. Princeton University Press. pp. 141–148. doi:10.2307/j.ctt7ztjmr.20. ISBN 9781400855896. JSTOR j.ctt7ztjmr.20.

External links

Media related to Duanwu Festival at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Duanwu Festival at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)