In the United States, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act defined the word "drug" as an "article intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease in man or other animals" and those "(other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals."[2] Consistent with that definition, the U.S. separately defines narcotic drugs and controlled substances, which may include non-drugs, and explicitly excludes tobacco, caffeine and alcoholic beverages.[3]

Federal drug policy

- History of United States drug prohibition

- Office of National Drug Control Policy

- Drug Enforcement Administration

War on drugs

The War on drugs is a campaign of prohibition and foreign military aid and military intervention undertaken by the United States government, with the assistance of participating countries, and the stated aim to define and reduce the illegal drug trade.[4][5] This initiative includes a set of drug policies of the United States that are intended to discourage the production, distribution, and consumption of illegal psychoactive drugs. The term "War on Drugs" was first used by President Richard Nixon in 1971.

Drug courts

The first Drug court in the United States took shape in Miami-Dade County, Florida in 1989 as a response to the growing crack-cocaine usage in the city. Chief Judge Gerald Wetherington, Judge Herbert Klein, then State Attorney Janet Reno and Public Defender Bennett Brummer designed the court for nonviolent offenders to receive treatment. This model of court system quickly became a popular method for dealing with an ever-increasing number of drug offenders. Between 1984 and 1999, the number of defendants charged with a drug offense in the Federal courts increased 3% annually, from 11,854 to 29,306. By 1999 there were 472 Drug Courts in the nation and by 2005 that number had increased to 1262 with another 575 Drug Courts in the planning stages; currently, all 50 states have working Drug Courts. There are currently about 120,000 people treated annually in Drug Courts, though an estimated 1.5 million eligible people are currently before the courts. There are currently more than 2,400 Drug Courts operating throughout the United States.

Pharmacological drugs

Doping in sports

Doping is the taking of performance-enhancing drugs, generally for sporting activities. Doping has been detected in many sporting codes, especially baseball and football.

| Substance | Athlete population | Percentage of athletes using substance[6] |

|---|---|---|

| Any substance banned by WADA | Elite athletes across sports (positive drug tests) | 2% over past year |

| Anabolic steroids | Professional football players (self-report) | 9% used at some point in career |

| Opiates | Professional football players (self-report) | 52% used at some point in career (71% of those misused at some point in career) |

| Smokeless tobacco | Professional basketball players (self-report) | 35%–40% over past year |

| Professional football players (self-report) | 20%–30% over past year |

Major League Baseball

The Mitchell Report

In December 2007 US Senator George Mitchell released Report to the Commissioner of Baseball of an Independent Investigation into the Illegal Use of Steroids and Other Performance Enhancing Substances by Players in Major League Baseball. Major League Baseball asked Mitchell to conduct an independent investigation to see how bad steroid use was in baseball. In the report, Mitchell covers many topics and he interviewed over 700 witnesses. He covers the effects of steroids on the human body. He also touches on human growth hormone effects. He reports on baseball's drug testing policies before 2002 and the newer policies after 2002. Mitchell also named 86 players in the report that had some kind of connection to steroids. Among those named were: Andy Pettitte, Roger Clemens, Barry Bonds, and Eric Gagne. To finish his report, Mitchell made suggestions to the Commissioner of Baseball about drug testing and violations of the drug testing policies. Mitchell also reported that he would provide evidence to support the allegations made against such players and would give them the opportunity to meet with him and give them a fair chance to defend themselves against the allegations. The report also includes a paper trail of evidence that states, "Former Mets club house attendant, Kirk Randomski sent performing enhancement drugs to the players mentioned in the report." Quinn, T.J. and Thompson, Teri Daily News Sports Writers [New York, N.Y.] CT. (2007):66[7][8]

Recreational drugs by type

Alcohol

Alcohol access

A survey of over 6000 teenagers revealed:

- Teenagers and young adults typically get their alcohol from persons 21 or older. The second most common source for high school students is someone else under age 21, and the third most common source for 18- to 20-year-old adults is buying it from a store, bar or restaurant (despite the fact that such sales are against the law).

- In the 12th grade, boys were more likely than girls to buy alcohol from a store, bar or restaurant.

- Teenagers with higher weekly incomes are more likely to buy alcohol from a store, bar or restaurant.

- It is easy to get alcohol at a party and from siblings or others 21 or older.[9]

How easy is it for youth to buy alcohol?

- When young females attempted to buy beer without an ID at liquor, grocery or convenience stores, 47–52% of the attempts, beer was sold (1, 2) and nearly 80% of all the stores sold beer to the buyers at least once in three attempts; nearly 25% sold beer all three times.(1)

- When young females attempted to buy beer without an ID at bars or restaurants, 50% of the attempts resulted in a sale to the buyer.(2)

- When young males and females attempted to buy beer without an ID at community festivals, 50% of the attempts resulted in a sale to the buyer.(3)[9]

Of note:

Cannabis

The use, sale, and possession of cannabis containing over 0.3% THC by dry weight in the United States, despite laws in many states permitting it under various circumstances, is illegal under federal law.[14] As a Schedule I drug under the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970, cannabis containing over 0.3% THC by dry weight (legal term marijuana) is considered to have "no accepted medical use" and a high potential for abuse and physical or psychological dependence.[15]

Cocaine

Cocaine is the second most popular illegal recreational drug in the United States behind cannabis,[16] and the U.S. is the world's largest consumer of cocaine.[17]

In 2020, the state of Oregon became the first U.S. state to decriminalize cocaine.[18][19] This new law prevents people with small amounts of cocaine from facing jail time. In 2020, the U.S. state of Oregon would also become the first state to decriminalize the use of heroin.[20] This measure will allow people with small amounts to avoid arrest.[21]

Methamphetamine

Psilocybin

In January 2019, the Oregon Psilocybin Society and research firm DHM Research found that 47 percent of Oregon voters supported the legalization of medical psilocybin, while 46 percent opposed it. The percentage of voters in favor increased to 64 percent after key elements of the ballot were clarified to the poll's participants.[23]

An October 2019 online poll conducted by research firm Green Horizons found that 38 percent of U.S. adults supported legalizing psilocybin "under at least some circumstances."[24]

In November 2020, a ballot measure to legalize medical psilocybin passed with 55.8% of voters in favor.[25]

Tobacco

_in_a_field_in_Intercourse%252C_Pennsylvania..jpg.webp)

Statistics in 2018 estimated that about 14.9% of adults (18 and over) had ever used e-cigarettes, and around 3.2% of all adults in the United States were current e-cigarette users. These same stats also noted that 34 million U.S. adults were current smokers, with E-cigarette usage being highest among current smokers and former smokers who are attempting or have recently quit cigarettes.[26]

Overall, it is estimated that 5.66 million adults in the US population reported current vaping 2.3%. From those users in the population, more than 2.21 million were current cigarette smokers (39.1%), more than 2.14 million were former smokers (37.9%), and more than 1.30 million were never smokers (23.1%).[27]

Costs

443,000 Americans die of smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke each year. For every smoking-related death, another 20 people suffer with a smoking-related disease. (2011)[28]

California's adult smoking rate has dropped nearly 50% since the state began the nation's longest-running tobacco control program in 1988. California saved $86 billion in health care costs by spending $1.8 billion on tobacco control, a 50:1 return on investment over its first 15 years of funding its tobacco control program.[28]

Critics

An estimated half a million children worked in the fields of America picking food as of 2012, although the precise number working in tobacco fields is unknown. In eastern North Carolina, children have been interviewed as young as fourteen who worked harvesting tobacco, and recent news reports describe children as young as nine and ten doing such work. Federal law provides no minimum age for work on small farms with parental permission, and children ages twelve and up may work for hire on any size farm for unlimited periods outside school hours. According to Human Rights Watch, farm-work is the most hazardous occupation open to children.[29][30]

Drug use and deaths per state

| State | Population (2010) | Drug Users (2010) | Drug Deaths (Total 2010) | Drug Deaths (per 100,000) | Federal Grants (2010) | Grant/Drug User |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4,779,736 | 06.73%[31] | 554 | 12 | $80,040,503 | $248.82 | |

| 710,231 | 11.79%[32] | 75 | 11 | $30,760,934 | $367.36 | |

| 6,392,017 | 08.95%[33] | 981 | 15.5 | $138,524,069 | $242.36 | |

| 2,915,918 | 07.96%[34] | 326 | 11.5 | $47,138,163 | $203.09 | |

| 37,253,956 | 09.07%[35] | 4178 | 11.4 | $832,107,905 | $246.26 | |

| 5,029,196 | 11.72%[36] | 747 | 15.4 | $111,188,470 | $188.64 | |

| 3,574,097 | 08.23%[37] | 444 | 12.7 | $103,493,029 | $351.84 | |

| 897,934 | 09.14%[38] | 102 | 11.8 | $24,161,839 | $294.40 | |

| 18,801,310 | 07.80%[39] | 2936 | 16.1 | $338,129,029 | $230.57 | |

| 9,687,653 | 07.32%[40] | 1043 | 10.6 | $321,114,660 | $452.83 | |

| 1,360,301 | 09.92%[41] | 142 | 11.1 | $37,176,146 | $275.50 | |

| 1,567,582 | 08.00%[42] | 133 | 8.9 | $21,076,027 | $168.06 | |

| 12,830,632 | 07.17%[43] | 1239 | 9.6 | $234,968,808 | $255.41 | |

| 6,483,802 | 08.79%[44] | 827 | 13.0 | $91,020,232 | $159.71 | |

| 3,046,355 | 04.08%[45] | 211 | 7.1 | $58,962,185 | $474.39 | |

| 2,853,118 | 06.77%[46] | 294 | 10.6 | $40,234,098 | $208.30 | |

| 4,339,367 | 08.41%[47] | 722 | 17 | $100,547,625 | $275.52 | |

| 4,533,372 | 07.16%[48] | 862 | 20.1 | $80,230,847 | $247.18 | |

| 1,328,361 | 09.09%[49] | 161 | 12.2 | $36,320,286 | $300.79 | |

| 5,773,552 | 07.29%[50] | 807 | 12.7 | $192,136,722 | $456.50 | |

| 6,547,629 | 08.87%[51] | 1003 | 15.6 | $245,061,344 | $421.96 | |

| 9,883,640 | 08.95%[52] | 1524 | 15.3 | $243,556,706 | $275.33 | |

| 5,303,925 | 08.24%[53] | 359 | 6.9 | $95,867,509 | $219.35 | |

| 2,967,297 | 06.39%[54] | 334 | 11.4 | $50,554,343 | $266.62 | |

| 5,988,927 | 07.38%[55] | 730 | 12.4 | $123,020,244 | $278.34 | |

| 989,415 | 10.02%[56] | 132 | 13.8 | $28,332,837 | $285.79 | |

| 1,826,341 | 06.43%[57] | 92 | 5.2 | $34,675,170 | $295.27 | |

| 2,700,551 | 09.35%[58] | 515 | 20.1 | $46,367,799 | $183.63 | |

| 1,316,470 | 12.15%[59] | 172 | 13.0 | $55,388,743 | $346.29 | |

| 8,791,894 | 06.42%[60] | 797 | 9.2 | $113,795,702 | $201.61 | |

| 2,059,179 | 10.07%[61] | 447 | 12.8 | $150,896,974 | $727.71 | |

| 19,378,102 | 09.82%[62] | 1797 | 9.2 | $1,875,136,099 | $985.39 | |

| 9,535,483 | 08.88%[63] | 1223 | 13.0 | $403,912,656 | $477.01 | |

| 672,591 | 05.3%[64] | 28 | 4.3 | $36,344,108 | $1,019.55 | |

| 11,536,504 | 07.61%[65] | 1691 | 14.7 | $207,925,242 | $236.84 | |

| 3,751,351 | 08.09%[66] | 687 | 19 | $67,359,062 | $221.95 | |

| 3,831,074 | 12.80%[67] | 564 | 15.1 | $104,298,167 | $212.69 | |

| 12,702,379 | 06.57%[68] | 1812 | 14.6 | $283,229,043 | $339.38 | |

| 1,052,567 | 13.34%[69] | 142 | 13.4 | $43,604,718 | $310.55 | |

| 4,625,364 | 06.70%[70] | 584 | 13.2 | $77,790,340 | $251.02 | |

| 814,180 | 06.28%[71] | 34 | 4.3 | $31,840,106 | $622.72 | |

| 6,346,105 | 08.22%[72] | 1035 | 16.8 | $107,211,391 | $205.52 | |

| 25,145,561 | 06.26%[73] | 2343 | 9.8 | $384,444,836 | $244.23 | |

| 2,763,885 | 06.24%[74] | 546 | 20.6 | $47,059,651 | $272.86 | |

| 625,741 | 13.73%[75] | 57 | 9.2 | $58,913,913 | $685.73 | |

| 8,001,024 | 07.33%[76] | 713 | 9.2 | $173,221,243 | $295.36 | |

| 6,724,540 | 09.59%[77] | 1003 | 15.5 | $130,527,165 | $202.40 | |

| 1,852,994 | 06.79%[78] | 405 | 22.4 | $45,059,469 | $358.13 | |

| 5,686,986 | 08.67%[79] | 639 | 11.4 | $107,259,369 | $217.54 | |

| 563,626 | 06.82%[80] | 68 | 13 | $12,483,581 | $324.76 | |

| 308,143,815 | 08.11% | 38260 | 12.4 | $8,304,469,106 | $332.19 |

See also

References

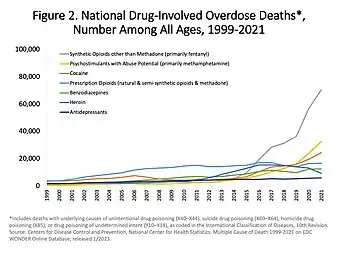

- ↑ Overdose Death Rates. By National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

- ↑ "Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act" U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved on 24 September 2007.

- ↑ "21 USC Sec. 802." New York City has seen a significant amount of drug use, coupled with an immigration crisis and a new law where bail is no longer necessary for drug offenders, putting them right back on the street further increasing drug consumption. Archived 2009-08-31 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved on 24 September 2007.

- ↑ Cockburn and St. Clair, 1998: Chapter 14

- ↑ Bullington, Bruce; Alan A. Block (March 1990). "A Trojan horse: Anti-communism and the war on drugs". Crime, Law and Social Change. Springer Netherlands. 14 (1): 39–55. doi:10.1007/BF00728225. ISSN 1573-0751.

- ↑ Reardon, Claudia (2014). "Drug Abuse in Athletes". Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 5: 95–105. doi:10.2147/SAR.S53784. PMC 4140700. PMID 25187752.

- ↑ "Files.mlb.com" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ "Sports.espn.go.com". Archived from the original on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- 1 2 "Youth Alcohol Access". Archived from the original on 21 June 2013.

- ↑ Total Annual Arrests in the US by Year and Type of Offense Archived April 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Drug War Facts. Page lists FBI Uniform Crime Reports sources. Page links to data table Archived December 7, 2020, at the Wayback Machine:

- ↑ Data table: Total Number of Arrests in the US by Year and Type of Offense Archived December 7, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Drug War Facts.

- ↑ Drugs and Crime Facts: Drug law violations and enforcement Archived December 25, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. From the United States Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports. Click on the charts to view the data.

- ↑ Marijuana Research: Uniform Crime Reports - Marijuana Arrest Statistics Archived December 21, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Has data table for earlier years. Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports.

- ↑ Clarke, Robert; Merlin, Mark (2013). Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany. University of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-520-95457-1. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ DEA (2013). "The DEA Position on Marijuana" (PDF). Dea.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 21, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ↑ "erowid.org". Archived from the original on October 6, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Field Listing – Illicit drugs (by country)". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-12-29. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ↑ "Oregon becomes first state to decriminalize hard drugs like heroin and cocaine". Fox News. 3 November 2020.

- ↑ "Oregon becomes the first state to decriminalize hard drugs like cocaine and heroin". CBS News. 4 November 2020.

- ↑ Cleve R. Wootson Jr.; Jaclyn Peiser (2020-11-04). "Oregon decriminalizes possession of hard drugs, as four other states legalize recreational marijuana". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. ISSN 0190-8286. OCLC 1330888409.

- ↑ "Oregon becomes first US state to decriminalize possession of hard drugs". TheGuardian.com. 4 November 2020.

- ↑ Andrew Whalen (July 3, 2019). "Magic Mushrooms Guide: Where Shrooms Are Legal and How To Take Psilocybin". Newsweek. Archived from the original on May 27, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ↑ Kyle Jaeger (January 22, 2019). "Most Oregon Voters Favor Legalizing Psilocybin Mushrooms For Medical Use, Poll Finds". Marijuana Moment. Archived from the original on May 7, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ↑ Edward Thomas (May 21, 2020). "Poll Indicates America's Growing Acceptance Of Psilocybin Mushrooms". High Times. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ↑ "Oregon Measure 109 Election Results: Legalize Psilocybin". The New York Times. 3 November 2020.

- ↑ "Products - Data Briefs - Number 365 - April 2020". www.cdc.gov. 2020-04-28. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ↑ Mayer, Margaret; Reyes-Guzman, Carolyn; Grana, Rachel; Choi, Kelvin; Freedman, Neal D. (2020-10-13). "Demographic Characteristics, Cigarette Smoking, and e-Cigarette Use Among US Adults". JAMA Network Open. 3 (10): e2020694. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20694. ISSN 2574-3805. PMC 8094416. PMID 33048127.

- 1 2 Adult Smoking in the US CDC September 2011

- ↑ The Hidden Victims of Tobacco HRW September 5, 2012

- ↑ Children in the Fields: North Carolina Tobacco Farms NBC August 9, 2012

- ↑ Alabama Drug Control Update

- ↑ Alaska Drug Control Update

- ↑ Arizona Drug Control Update

- ↑ Arkansas Drug control Update

- ↑ California Drug Control Update

- ↑ Colorado Drug Control Update

- ↑ Connecticut Drug Control Update

- ↑ Delaware Drug Control Update

- ↑ Florida Drug Control Update

- ↑ Georgia Drug Control Update

- ↑ Hawaii Drug Control Update

- ↑ Idaho Drug Control Update

- ↑ Illinois Drug Control Update

- ↑ Indiana Drug Control Update

- ↑ Iowa Drug Control Update

- ↑ Kansas Drug Control Update

- ↑ Kentucky Drug Control Update

- ↑ Louisiana Drug Control Update

- ↑ Maine Drug Control Update Archived September 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Maryland Drug Control Update

- ↑ Massachusetts Drug Control Update

- ↑ Michigan Drug Control Update Archived January 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Minnesota Drug Control Update

- ↑ Mississippi Drug Control Update

- ↑ Missouri Drug Control Update

- ↑ Montana Drug Control Update

- ↑ Nebraska Drug Control Update

- ↑ Nevada Drug Control Update

- ↑ New Hampshire Drug Control Update

- ↑ New Jersey Drug Control Update

- ↑ New Mexico Drug Control Update

- ↑ New York Drug Control Update

- ↑ North Carolina Drug Control Update

- ↑ North Dakota Drug Control Update

- ↑ Ohio Drug Control Update

- ↑ Oklahoma Drug Control Update

- ↑ Oregon Drug Control Update

- ↑ Pennsylvania Drug Control Update

- ↑ Rhode Island Drug Control Update

- ↑ South Carolina Drug Control Update

- ↑ South Dakota Drug Control Update

- ↑ Tennessee Drug Control Update

- ↑ Texas Drug Control Update

- ↑ Utah Drug Control Update

- ↑ Vermont Drug Control Update

- ↑ Virginia Drug Control Update

- ↑ Washington Drug Control Update

- ↑ West Virginia Drug Control Update

- ↑ Wisconsin Drug Control Update

- ↑ Wyoming Drug Control Update

Further reading

- DeGrandpre, Richard J (2006). The cult of pharmacology : how America became the world's most troubled drug culture. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822338819.