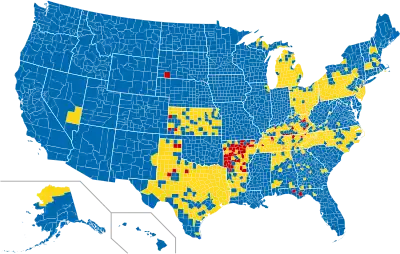

Red = dry counties, where selling alcohol is prohibited

Yellow = semi-dry counties, where some restrictions apply

Blue = no restrictions

In the United States, a dry county is a county whose government forbids the sale of any kind of alcoholic beverages. Some prohibit off-premises sale, some prohibit on-premises sale, and some prohibit both. Dozens of dry counties exist across the United States, mostly in the South.

A number of smaller jurisdictions also exist, such as cities, towns, and townships, which prohibit the sale of alcoholic beverages and are known as dry cities, dry towns, or dry townships. Dry jurisdictions can be contrasted with "wet" (in which alcohol sales are allowed and regulated) and "moist" (in which some products or establishments are prohibited and not fully regulated, or a dry county containing wet cities).

Background

History

In 1906, just over half of U.S. counties were dry. The proportion was larger in some states; for example, in 1906, 54 of Arkansas's 75 counties were completely dry, influenced by the anti-liquor campaigns of the Baptists (both Southern and Missionary) and Methodists.[1]

Although the 21st Amendment repealed nationwide Prohibition in the United States, prohibition under state or local laws is permitted.[2] Prior to and after repeal of nationwide Prohibition, some states passed local option laws granting counties and municipalities, either by popular referendum or local ordinance, the ability to decide for themselves whether to allow alcoholic beverages within their jurisdiction.[3] Many dry communities do not prohibit the consumption of alcohol, which could potentially cause a loss of profits and taxes from the sale of alcohol to their residents in wet (non-prohibition) areas.

The reason for maintaining prohibition at the local level is often religious in nature, as many evangelical Protestant Christian denominations discourage the consumption of alcohol by their followers (see Christianity and alcohol, sumptuary law, and Bootleggers and Baptists).

A 2018 study of wet and dry counties in the U.S. found that "Even controlling for current religious affiliations, religious composition following the end of national Prohibition strongly predicts current alcohol restrictions."[4]

In rural Alaska, restrictions on alcohol sales are motivated by problems with alcohol use disorder and alcohol-related crime.[5]

Transport

Since the 21st Amendment repealed nationwide Prohibition in the United States, alcohol prohibition legislation has been left to the discretion of each state, but that authority is not absolute. States within the United States and other sovereign territories were once assumed to have the authority to regulate commerce with respect to alcohol traveling to, from, or through their jurisdictions.[6] However, one state's ban on alcohol may not impede interstate commerce between states who permit it.[6] The Supreme Court of the United States held in Granholm v. Heald (2005)[6] that states do not have the power to regulate interstate shipments of alcoholic beverages. Therefore, it may be likely that municipal, county, or state legislation banning possession of alcoholic beverages by passengers of vehicles operating in interstate commerce (such as trains and interstate bus lines) would be unconstitutional if passengers on such vehicles were simply passing through the area. Following two 1972 raids on Amtrak trains in Kansas and Oklahoma, dry states at the time, the bars on trains passing through the two states closed for the duration of the transit, but the alcohol stayed on board.[7][8]

Prevalence

A 2004 survey by the National Alcohol Beverage Control Association found that more than 500 municipalities in the United States are dry, including 83 in Alaska. Of Arkansas's 75 counties, 34 are dry.[9][10] 36 of the 82 counties in Mississippi were dry or moist[11] by the time that state repealed its alcoholic prohibition on January 1, 2021, the date it came into force, making all its counties "wet" by default and allowing alcohol sales unless they vote to become dry again through a referendum.[12] In Florida, three of its 67 counties are dry,[13] all of which are located in the northern part of the state, an area that has cultural ties to the Deep South.

Moore County, Tennessee, the home county of Jack Daniel's, a major American producer of whiskey,[14] is a dry county and so the product is not available at stores or restaurants within the county. The distillery, however, sells commemorative bottles of whiskey on site.[15]

Traveling to purchase alcohol

A study in Kentucky suggested that residents of dry counties have to drive farther from their homes to consume alcohol, thus increasing impaired driving exposure,[16] although it found that a similar proportion of crashes in wet and dry counties are alcohol-related.

Other researchers have pointed to the same phenomenon. Winn and Giacopassi observed that residents of wet counties most likely have "shorter distances (to travel) between home and drinking establishments".[17] From their study, Schulte and colleagues postulate that "it may be counter productive in that individuals are driving farther under the influence of alcohol, thus, increasing their exposure to crashes in dry counties".[16]

Data from the National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration (NHTSA) showed that in Texas, the fatality rate in alcohol-related accidents in dry counties was 6.8 per 10,000 people over a five-year period. That was three times the rate in wet counties: 1.9 per 10,000.[18][19] A study in Arkansas came to a similar conclusion - that accident rates were higher in dry counties than in wet.[20]

Another study in Arkansas noted that wet and dry counties are often adjacent and that alcoholic beverage sales outlets are often located immediately across county or even on state lines.[21]

Tax revenue

Another issue a dry city or county may face is the loss of tax revenue because drinkers are willing to drive across city, county or state lines to obtain alcohol. Counties in Texas have experienced this problem, which led to some of its residents to vote towards going wet to see their towns come back to life commercially. Although the idea of bringing more revenue and possibly new jobs to a town may be appealing from an economic standpoint, moral opposition remains present.[22]

Crime

One study finds that the shift from bans on alcohol to legalization causes an increase in crime.[23] The study finds that "a 10% increase in drinking establishments is associated with a 3 to 5% increase in violent crime. The estimated relationship between drinking establishments and property crime is also positive, although smaller in magnitude".[23]

Dry and moist counties in Kentucky had a higher rate of meth lab seizures than wet counties; a 2018 study of Kentucky counties concluded that "meth lab seizures in Kentucky would decrease by 35% if all counties became wet."[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Barnes, Kenneth C. (2016). Anti-Catholicism in Arkansas: How Politicians, the Press, the Klan, and Religious Leaders Imagined an Enemy, 1910–1960. University of Arkansas Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1682260166.

- ↑ "-National Constitution Center". National Constitution Center – constitutioncenter.org. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Control State Directory and Info". www.nabca.org. National Alcohol Beverage Control Association. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017.

- 1 2 Fernandez, Jose; Gohmann, Stephan; Pinkston, Joshua C. (April 2018). "Breaking Bad in Bourbon Country: Does Alcohol Prohibition Encourage Methamphetamine Production?". Southern Economic Journal. 84 (4): 1001–1023. doi:10.1002/soej.12262.

- ↑ Patkotak, Elise (April 1, 2015). "Wet, damp or dry, Alaska communities suffer scourge of alcohol abuse". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- 1 2 3 544 U.S. 460 (2005)

- ↑ St. John, Sarah (July 19, 1972). "40 years ago: Kansas AG raids Amtrak train, confiscates liquor". Lawrence Journal-World. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018.

- ↑ Adams, Cecil (August 13, 2010). "No Booze, Oklahoma? No Railroad For You!". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Wet Counties with Their Respective Exceptions". dfa.arkansas.gov. Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ↑ "2021 Unofficial Local Option Election Status". dfa.arkansas.gov. Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Mississippi Alcoholic Beverages Wet-Dry Map". Archived from the original on June 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Mississippi's governor has signed into law a repeal of alcoholic prohibition in the state". WTVA. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ↑ "Should Suwannee County remain dry? Voters will decide". Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ Stengel, Jim (January 9, 2012). "Jack Daniel's Secret: The History of the World's Most Famous Whiskey". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Lynchburg, Moore County High School Raiders, Tennessee, Christmas, Tims Ford State Park, Lake, Motlow Bucks, Jack Daniels, Sign Dept". www.themoorecountynews.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016.

- 1 2 Schulte Gary, Sarah Lynn; Aultman-Hall, Lisa; McCourt, Matt; Stamatiadis, Nick (2003). "Consideration of driver home county prohibition and alcohol-related vehicle crashes". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 35 (5): 641–648. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(02)00042-8. PMID 12850064.

- ↑ Winn, Russell; Giacopassi, David (1993). "Effects of county-level alcohol prohibition on motor vehicle accidents". Social Science Quarterly. 74 (4): 783–792. JSTOR 42863249.

- ↑ "'Dry Towns' throughout the US". American Addiction Centers, Inc. October 22, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ↑ Kelleher, Kelly (1997). "Social and Economic Consequences of Rural Substance Abuse, chapter in Drug Abuse Research" (PDF). NIH. pp. 196–219. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ↑ Stewart, Patrick A.; Reese, Catherine C.; Brewer, Jeremy (2004). "Effects of Prohibition in Arkansas Counties". Politics & Policy. 32 (4): 595–613. doi:10.1111/j.1747-1346.2004.tb00197.x. S2CID 143975978.

- ↑ Combs, H. Jason (2005). "The wet-dry issue in Arkansas". The Pennsylvania Geographer. 43 (2): 66–94.

- ↑ Hampson, Rick (August 1, 2010). "Dry America's not-so-sober reality: Its Shrinking Fast". USA Today. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- 1 2 Anderson, D. Mark; Crost, Benjamin; Rees, Daniel (December 1, 2016). "Wet Laws, Drinking Establishments, and Violent Crime". The Economic Journal. 128 (611): 1333–1366. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12451. hdl:10419/107493. ISSN 1468-0297. S2CID 154591383.