_(14562137308).jpg.webp)

Waterfowl hunting (also called wildfowling or waterfowl shooting in the UK) is the practice of hunting aquatic birds such as ducks, geese and other waterfowls or shorebirds for food and sport.

Many types of ducks and geese share the same habitat, have overlapping or identical hunting seasons, and are hunted using the same methods. Thus it is possible to take different species of waterfowl in the same outing. Waterfowl can be hunted in crop fields where they feed, or, more frequently, on or near bodies of water such as rivers, lakes, ponds, wetlands, sloughs, or sea coasts.

History

Prehistoric waterfowl hunting

Wild waterfowl have been hunted for food, down, and feathers worldwide since prehistoric times. Ducks, geese, and swans appear in European cave paintings from the last Ice Age, and a mural in the Ancient Egyptian tomb of Khnumhotep II (c. 1900 BCE) shows a man in a hunting blind capturing swimming ducks in a trap.[1] Muscovy ducks were depicted in the art of the Moche culture of ancient Peru by 200 BCE, and were likely hunted by many people of the Americas before then.[2]

Rise of modern waterfowl hunting

Hunting with shotguns began in the 17th century with the matchlock shotgun. Later flintlock shotguns and percussion cap guns were used. Shotguns were loaded with black powder and lead shot through the muzzle in the 17th century to the late 19th century. The transition from flint to "detonating" or percussion lock firearms and from muzzle to breech loading guns was largely driven by innovations made by English gun makers such as Joseph Manton, at which time wildfowling was extremely popular in England both as a pastime and as a means of earning a living, as described by Col. Peter Hawker in his diaries.[3] Damascus barrels are safe to shoot (where proofed) only with black powder charges. When smokeless powder was invented in the late 19th century, steel barrels were made. Damascus barrels which were made of a twisted steel could not take the high pressure of smokeless powder. Fred Kimble, Tanner, and Adam, duck hunters from Illinois, invented the shotgun choke in 1886. This is a constriction at the end of the barrel. This allowed for longer range shooting with the shotgun and kept the pattern of shot tighter or looser according to which type of choke is being used. Until 1886, shotguns had cylinder bore barrels which could only shoot up to 25 yards, so duck hunting was done at close range. After 1886, market hunters could shoot at longer ranges up to forty five yards with a full choke barrel and harvest more waterfowl. Shotguns became bigger and more powerful as steel barrels were being used, so the range was extended to sixty yards.

Pump shotguns were invented in the late 19th century, and the semi-automatic 12 gauge shotgun was developed by John Browning in the very early 20th century, which allowed commercial hunters to use a four-shell magazine (five including the one in the chamber) to rake rafts of ducks on the water or kill them at night, in order to kill larger numbers of waterfowl for the commercial markets. Even during the Great Depression years, a brace of canvasbacks could be sold to restaurants before legislation and hunting organizations pushed for greater enforcement. Once waterfowlers had access to these guns, this made these men more proficient market hunters. These guns could fire five to seven shots, therefore hunters were having bigger harvests.

Early European settlers in America hunted waterfowl with great zeal, as the supply of waterfowl seemed unlimited in the coastal Atlantic regions. During the fall migrations, the skies were filled with waterfowl. Places such as Chesapeake Bay, Delaware Bay, and Barnaget Bay were hunted extensively.

As more immigrants came to America in the late 18th and 19th centuries, the need for more food became greater. Market hunting started to take form, to supply the local population living along the Atlantic coast with fresh ducks and geese. Men would go into wooden boats and go out into the bays hunting, sometimes with large shotguns. They would bring back a wooden barrel or two of ducks each day. Live ducks were used as decoys as well as bait such as corn or other grain to attract waterfowl.

The rise of modern waterfowl hunting is tied to the history of the shotgun, which shoots a pattern of round pellets making it easier to hit a moving target. In the 19th century, the seemingly limitless flocks of ducks and geese in the Atlantic and Mississippi Flyways of North America were the basis for a thriving commercial waterfowl hunting industry. With the advent of punt guns – massive, boat-mounted shotguns that could fire a half-pound of lead shot at a time – hunters could kill dozens of birds with a single blast. This was the four and six gauge shotgun. This period of intense commercial waterfowl hunting is vividly depicted in James Michener's historical novel Chesapeake.

Although edible, swans are not hunted in many Western cultures due to hunting regulations, and swans were historically a royal prerogative. Swans are hunted in the Arctic regions.

Conservation and the Duck Stamp Act

Around the start of the 20th century, commercial hunting and loss of habitat due to agriculture led to a decline in duck and goose populations in North America, along with many other species of wildlife. The Lacey Act of 1900, which outlawed transport of poached game across state lines, and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which prohibited the possession of migratory birds without permission (such as a hunting license), marked the dawn of the modern conservation movement.

In 1934, at the urging of editorial cartoonist and conservationist J.N. "Ding" Darling, the United States government passed the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, better known as the Federal Duck Stamp Act. This program required hunters to purchase a special stamp, in addition to a regular hunting license, to hunt migratory waterfowl. This stamp cost two dollars in 1934 but today the price is twenty-five dollars. As of 2007 there is also an "E-duck" stamp available for seventeen dollars where duck hunting is immediately authorized and the physical stamp is mailed later.[4] The stamp is valid from July 1 to June 30 of each year. The stamp may be raised to twenty dollars in the near future. Revenues from the stamp program provided the majority of funding for conservation for many decades. The stamp funded the purchase of 4.5 million acres (18,000 km2) of National Wildlife Refuge land for waterfowl habitat since the program's inception in 1934. The Duck Stamp act has been described as "one of the most successful conservation programs ever devised."[5] Duck stamps have also become collectible items in their own right. Stamps must not be signed to be of value.[6]

England sold its first duck stamp in 1991, featuring ten pintails flying along the coast of England. The stamp cost five pounds sterling.

Species of waterfowl hunted

In North America a variety of ducks and geese are hunted, the most common being mallards, Canada geese, snow geese, canvasback, redhead, northern pintail, gadwall, ruddy duck, coots, common, hooded and red-breasted merganser (often avoided because of its reputation as a poor-eating bird with a strong flavor). Also hunted are black duck, wood duck, blue-winged teal, green-winged teal, bufflehead, northern shoveler, American wigeon, and goldeneye. Sea ducks include oldsquaw (long tailed duck), eider duck, and scoter.

Swans are hunted in only a few states in the United States, but are hunted along with other wildfowl in many other countries. In the UK, swan hunting is illegal because they are considered property of the queen.

In the Australian states of Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia and the Northern Territory, species hunted under permit include the Pacific black duck, Australian wood duck, chestnut teal, grey teal, pink-eared duck and mountain duck.

Since 1990, recreational duck hunting on public land has been banned in Western Australia but it still allows Australian wood ducks to be shot on private property throughout the year with few restrictions.

Modern hunting techniques

The waterfowl hunting season is generally in the autumn and winter. Hunting seasons are set by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in the United States. In the autumn, the ducks and geese have finished raising their young and are migrating to warmer areas to feed. The hunting seasons usually begin in October and end in January. Extended goose seasons can go into April, the Conservation Order by the U.S.F.W.S.

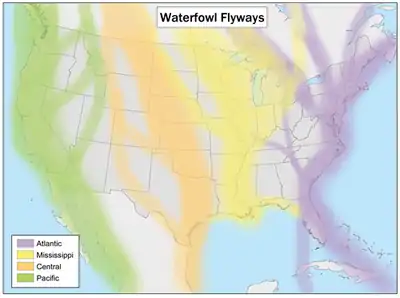

There are four large flyways in the United States that the waterfowl follow: the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central and Pacific Flyways.

There are several items used by almost all waterfowl hunters: a shotgun, ammunition, a hunting blind, decoys, a boat, and a duck or goose call. Unless float hunting or jump shooting—decoys are used to lure the birds within range, and the blind conceals the hunter. When a hunter or hunters sees the waterfowl, he or she begins calling with the duck or goose call. Once the birds are within range, the hunters rise from the blind and quickly shoot the birds before they are frightened off and out of shooting range. Duck or goose calls are often used to attract birds; sometimes calls of other birds will also be simulated to convince the birds that there is no danger.

Hunters position themselves in blinds near rivers, lakes, ponds or in agriculture fields planted with corn, barley, wheat or millet. Hunters build blinds to conceal themselves from waterfowl, as waterfowl have sharp eyes and can see colors. That is why hunters use camouflage. Waterfowl hunters also often use dogs to retrieve dead or injured birds in the water. There are many retriever breeds, such as Labrador Retrievers and Chesapeake Bay Retrievers, specifically bred for the task. Hunters also may use a boat to get downed birds. Some hunters use boats as blinds or float rivers in search of waterfowl. When the ducks see the hunters in the boat, ducks flush off the water and hunters shoot. Then birds are collected and placed in the boat.

Each hunter prefers a certain type of weather condition, depending on the type of hunting setting. Some hunters prefer sunny days vs cloudy or rainy days. However, ducks and geese fly more extensively and actively on cloudy days, rain or snow. There is an old hunters tale that if you see swans flying, ducks will be close behind.

Shotguns

While hunting of waterfowl was on the rise in America and Europe, hunters used a wide array of shotguns. Shotguns used included 4 gauge, 6 gauge, 8 gauge, 10 gauge, 12 gauge, 16 gauge, 18 gauge, 20 gauge, 24 gauge, 28 gauge and .410. The 12 gauge turns out to be the most popular with hunters then and now due to its weight to firepower ratio. Punt guns, along with both the four and six gauge, were mounted to small boats due to their weight and recoil. The eight gauge was hand held at about fourteen pounds in weight with approximately 2.5 ounces of shot. The largest gun used today in the United States is the 10 gauge shotgun, shooting a 3.5 inch shell that holds up to 2.5 ounces of shot. These shotguns can kill ducks at up to 60 yards. By far the most common modern shotgun used for waterfowl hunting is the twelve gauge. With the development of higher-pressure 3.5 inch shells, 12 gauge shotguns can deliver close to the power and shot load of a ten gauge out of a lighter gun with less recoil. Modern 16 gauge shotguns are rare, with more people choosing the higher power twelve gauge or lower recoil of the 20 gauge. 20 gauge shotguns are less commonly used for long-range waterfowl hunting, but are preferred by hunters who do not like the weight of the twelve gauge. 28 gauge and .410 bore shotguns are rarely used due to the gun's inability to ensure clean kills at ranges of 40 to 50 yards. Some hunting guns have camouflage-patterned stocks and low-gloss finishes on the metal to reduce their visibility to waterfowl.

Although it is legal to use a bow to take migratory waterfowl in many areas, most hunters prefer taking migratory birds with a shotgun because of the great difficulty of striking a moving bird with an arrow. Taking migratory birds with a handgun, carbine, or rifle is illegal due to the great distances that bullets travel, making them unsafe.

Shotgun ammunition

Since the 16th century, lead shot has been used in waterfowl hunting. Lead shot was originally poured down the barrel. Later, shells were made of paper and brass in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. In the early 1960s, manufacturers began making shot-shells of plastic. In the late 1960s, it was determined that lead shot poisoned waterfowl eating in shallow water areas where there was heavy hunting. In 1974, steel shot shells were offered for sale to hunters at the Brigantine Waterfowl Refuge in southern New Jersey, and at Union County State Fish & Wildlife area in Union County, Illinois, by Winchester at five dollars a box. These shells were marked "Experimental" and were orange in color.

Prior hunting with lead shot, along with the use of lead sinkers in angling, has been identified as a major cause of lead poisoning in waterfowl, which often feed off the bottom of lakes and wetlands where lead shot collects.[7][8] In the United States, UK, Canada, and many western European countries (France as of 2006), all shot used for waterfowl must now be non-toxic, and therefore may not contain any lead. Steel is the cheapest alternative to lead. However, some hunters do not like its shooting properties, as steel is significantly less dense than lead. Therefore, its effective range is decreased due to rapidly decreasing velocity of the shot: thirty to forty yards is considered its maximum effective range for duck hunting. Many companies have improved steel shot by increasing muzzle-velocity, by using fast burning powder such as rifle powder thus making more consistent 'shot' or pellet patterns. Steel shot now travels at 1400 to 1500 feet per second. However, any use of steel shot requires a shotgun barrel with thicker walls and a specially-hardened bore, resulting in a heavier gun.

Within recent years, several companies have created "heavier than lead" non-toxic shot out of tungsten, bismuth, or other elements with a density similar to or greater than lead. These shells have more consistent patterns and greater range than steel shot. The increase in performance comes at a higher cost. Shell boxes often cost more than thirty dollars a box for twenty five shells.

Hunters use pellet sizes 4, 3, and 2 for ducks, and 2, BB, BBB and T shot for geese. Buckshot is illegal.

Blinds

A hunting blind is a structure intended to conceal hunters, dogs, and equipment from the intended prey. Blinds can be temporary or permanent.

A blind may be constructed out of plywood, lumber, large logs or branches, burlap fiber, plastic or cotton camouflage, or natural vegetation. Many of these permanent blinds look like a small shack with an opening that faces the water and a portion of the sky. Blinds can be as simple as natural vegetation piled onto branches, or they can be small outbuildings with benches, tables, heaters, and other conveniences.

Temporary blinds are common in protected and public areas where permanent fixture blinds are forbidden. Many are tent-like "pop-up" blinds which are quick and easy to erect. Boat blinds are used to conceal a hunter while hunting from a boat. Boat blinds can be handmade or are available from manufacturers.

There are two common types of blinds for land and field-based waterfowl hunting: pit blinds and layout blinds. The pit blind can be a solid structure that is placed into a hole in the ground or on the bank of a waterbody. Since pit blinds rest below the top of the surrounding soil, some structural strength is required to prevent the soil from collapsing into the blind. Commercially available blinds can be made from fiberglass, polyethylene or even lightweight metals. Homemade blinds can also be constructed of wood, but typically cannot withstand the moisture of an underground habitat. Concrete walls are also constructed to form pit blinds typically on land owned or controlled by hunt clubs since this creates a permanent structure.

Pit blind amenities can vary greatly from a basic blind with sticks or other temporary camouflage to elaborate multi-level blinds with small quarters for sleeping or cooking. Most pit blinds will have some form of movable door or slide that can be opened quickly when waterfowl are approaching while still allowing the hunters a good view while closed. Camouflage netting or screens are common materials for the movable top. One common drawback to pit blinds is their propensity to accumulate water. Especially in marsh or wetland areas, the soil can hold a large amount of moisture. Pit blinds are sometimes fitted with sump pumps or even hand-operated pumps to assist the hunters in draining any water that has invaded the blind.

Layout blinds allow a hunter to have a low profile in a field without digging a hole. They are made of an aluminum metal frame and a canvas cover. Most modern commercial layout blinds are fitted with spring-loaded flaps on top that retract when the hunter is ready to fire. The layout blind allows the hunter to lie prone in the blind with only the head or face exposed to allow good visibility. Newer blinds also have a screen that provides a one-way view outside the blind to conceal the hunter, but allow him/her to observe the waterfowl. When birds are in range, the hunter can open the flaps and quickly sit up to a shooting position. Layout blinds come in many different colors and patterns from plain brown to new camouflage patterns that simulate forage found in typical hunting locations. A favorite trick of savvy hunters is to use loose forage found in the specific field being hunted to camouflage the layout blind. Most blinds are fitted with canvas loops designed to hold stalks, grass or other material.

Blinds are known by different names in different countries. In New Zealand, for instance, the term maimai (possibly from the Australian term "mia-mia" for a temporary shelter) is used for a permanent or semi-permanent hide or blind.[9]

Decoys

_(14755150402).jpg.webp)

Decoys are replica waterfowl that are used to attract birds to a location near the hunters; an important piece of equipment for the waterfowler. Using a good spread of decoys and calling, an experienced waterfowl hunter can successfully bag ducks or geese if waterfowl are flying that day. The first waterfowl decoys were made from vegetation such as cattails by Native Americans. In the 18th century, duck decoys were carved from soft wood such as pine. Many decoys were not painted. Live birds were also used as decoys. They were placed in the water and had a rope and a weight at the end of the rope so the duck could not swim or fly away. This method of hunting became illegal in the 1930s. By the end of the 20th century, collectors started to search for high quality wooden duck decoys that were used by market hunters in the late 19th century or early 20th century. Decoys used in Chesapeake Bay, Delaware Bay, Barnegat Bay, and North Carolina's Core Sound, and the famous Outerbanks (OBX) are highly sought after. Most decoys were carved from various types of wood that would withstand the rigors of many seasons of hunting. Highly detailed paint and decoy carvings that even included the outlines of tail or wing feathers turned the duck decoy into a work of art. Today, many collectors search estate sales, auctions, trade shows, or other venues for vintage duck decoys. In the historic Atlantic Flyway, North Carolina's "Core Sound Decoy Festival" draws in excess of 40,000 visitors to the little community of Harker's Island, NC the first weekend in December each year, and Easton, MD with their Wildfowl Festival in the month of November draws a great many people to that old goose hunting community on the Eastern Shore.

Modern decoys are typically made from molded plastic; that began in the 1960s. Making decoys of plastic, decoys can be made many times faster than carving from wood. The plastic allows a high level of detail, a resilient product and reasonable cost. Most are still hand painted. Most modern decoys are fitted with a "water keel" which fills with water once the decoy is immersed in water or a "weighted keel" filled with lead. Both types of keel help the decoy stay upright in wind or high waves. Weighted keel decoys look more realistic by sitting lower in the water. This also allows for decoys to be thrown into the water and the decoy to float upright. The obvious drawback to weighted keels are the added weight when carrying decoys for long distances. Decoys are held in place by some type of sinker or weight and attached via line to the decoy. Various weight designs allow the line to be wrapped around the decoy when not in use and secured by folding or attaching the lead weight to the decoy.

Decoys are placed in the water about 30 to 35 yards from the hunters. Usually a gap is in the decoy spread to entice live ducks to land in the gap.

Recently, decoys have been introduced that provide lifelike movement that adds to the attraction for waterfowl. Shakers are decoys with a small electric motor and an offset weighted wheel. As the wheel turns it causes the decoy to "shake" in the water and create realistic wave rings throughout the decoy spread. Spinning wing decoys are also fitted with an electric motor and have wings made of various materials. As the wings spin an optical illusion is created simulating the wing beats for landing birds. These decoys can be quite effective when hunting waterfowl and have been banned in some states. Other types of movement decoys include swimming decoys and even kites formed like geese or ducks. The use of UV paint has also been suggested for decoys. Unlike humans, it is possible for wildlife to see UV colors and decoys so patterned may appear more authentic.

Boats

Boats are used while hunting to set up decoys, pick up birds, or travel to and from hunting areas. For general camouflage, boats are often painted some combination of brown, tan, green, and black. They can also be covered with grass or burlap and used as a hunting blind, known as sneak boat hunting. Boats for hunting are generally either propelled by motor or with oars. Most popular are flat-bottomed boats (usually jon boats) for increased stability, with keels made of wood or aluminum between 10 and 16 feet (3.0 and 4.9 m) long. Painted kayaks or canoes made of aluminum or fiberglass reinforced with Kevlar are also used; these can navigate shallow streams or small narrow rivers in search of waterfowl. Care must be taken when shooting from boats as hunters may fall overboard due to loss of balance when shooting at waterfowl. Pursuing diving ducks in lakes, bays or sounds in the United States requires larger and more stable boats, as small boats have been known to capsize, wherein hunters can drown by hypothermia. Sink boxes, boats that conceal the hunter under the water surface, are illegal to use in the United States, but technically legal in Canada.

Clothing

Duck season takes place in the fall and winter where the weather can be harsh. Waterproof clothing is critical to duck hunting. Most duck hunters hunt over water, and they stand in water or in a boat. In order to stand in the water and stay dry the hunter must wear waders. Waders are waterproof pants (usually made of a neoprene-like material) that have attached boots and are completely waterproof. Typical waders are chest-high, but waist-high and knee-high waders are sometimes used in shallow water. Duck hunting is a cold sport and the hunter must be well insulated from the cold. Ducks also have superior vision and can see color, which is why hunters must wear clothing that is well camouflaged. Camouflage clothing is various shades of brown or green or brown and green combined. Therefore, hunters wear camouflage similar to the area they are hunting so the ducks do not see the hunters. Face masks are often worn so the ducks do not see the hunters' faces, and camouflage gloves are also worn.

Dogs

Duck hunters quite often employ a dog to retrieve downed birds. Most often hunters use a Labrador Retriever, Golden Retriever or Chesapeake Bay Retriever to retrieve waterfowl. The use of a dog provides a number of advantages. As duck hunting often takes place in cold wet locations, the use of a dog frees the hunter from potentially dangerous forays into cold water to retrieve the bird. Such efforts can be dangerous for the hunter, but are managed by a dog quite easily. It also allows for the recovery of wounded birds that might otherwise escape. A dog's acute sense of smell allows them to find the wounded birds in swamps or marshes where weeds can allow a duck to hide. The use of a dog ensures that a higher percentage of the birds shot end up on the table. A disadvantage of having dogs in the duck blind, is that some dogs are not well-trained to sit still and can potentially ruin a good hunt. Dogs that run into the water looking for birds when guns are fired, rather than waiting until sent or released create a hazard to the dog and hunters. Nevertheless, dogs are considered the greatest conservation tool known to waterfowlers.

Hunting guides

In the United States, professional hunting guides are used by waterfowlers who do not know the local area. They are paid to take clients to hunt on leased, or private property, or hunting in local areas in which these professional guides know where to hunt in large public waterfowl hunting areas. If they use an outboard engine on their boat, they must be registered by the USCG as an OUPV operator in all fifty states, and have that license in their boat during the time of operation, and many states require all waterfowl guides to be registered via the state DNR hunting license. Waterfowlers normally employ a guide for a half-day or a whole day of hunting. The cost of hiring a guide varies from one hundred fifty dollars for a half day to four hundred dollars for a day. Guides have boats, blinds, decoys, and dogs for retrieving ducks or geese. They know the flight patterns of the game and know how to call ducks or geese in. They know how to set up decoys. Some guides specialize in certain types of waterfowl while others will be more generalists. Some guides specialize in sea hunting while others will specialize in bay hunting, river hunting, lake hunting, or swamp hunting. Guides may have houses for hunters to sleep in for the night. They may provide the service of cleaning the game and keeping it on ice in coolers or refrigerators. Guides may have coffin blinds or more fancy house blinds, that provide seats and heating. Guides are usually registered with the state that they guide in.

Wildfowling in the UK

In Britain, the term "hunting" is generally reserved for the pursuit of game on land with hounds, so the sport is generally known as "wildfowl shooting" or "wildfowling" rather than "hunting."

Wild ducks and geese are shot over foreshores and inland and coastal marshes in Europe. Birds are shot with a shotgun, and less commonly, a large single barreled gun mounted on a small boat, known as a punt gun. Due to the ban on the use of lead shot for hunting wildfowl or over wetlands, many wildfowlers are switching to modern guns with stronger engineering to allow the use of non-toxic ammunition such as steel or tungsten based cartridges. The most popular bore is the 12-gauge.

Only certain 'quarry' species of wildfowl may legally be shot in the UK, and are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. These are mallard, Eurasian wigeon, teal, pochard, shoveler, pintail, gadwall, goldeneye, tufted duck, Canada goose, greylag goose and pink-footed goose. Other common quarry targets for the wildfowler include the common snipe.

An intimate knowledge of the quarry and its habitat is required by the successful wildfowler. Shooting will normally occur during the early morning and late afternoon 'flights', when the birds move to and from feeding and roosting sites. The wildfowler is not looking for a large bag of quarry, and his many hours of effort are rewarded by even a single bird. It is recommended that wildfowlers always shoot with a dog, or someone with a dog, to retrieve shot birds on difficult estuarine terrain. The favourites on the table are mallard, wigeon and teal.

Wildfowling has come under threat in recent years through legislation. Destruction of habitat also has played a large part in the decline of shooting areas, and recently in the UK "right to roam" policies mean that wildfowlers' conservation areas are at risk. However, in most regions, good relationships exist between wildfowlers, conservationists, ramblers and other coastal area users.

In the UK wildfowling is largely self-regulated. Their representative body, WAGBI (Wildfowlers Association of Great Britain and Ireland), was founded in 1908 by Stanley Duncan in Hull. This Association changed its name in 1981 to become the British Association for Shooting and Conservation (BASC) and now represents all forms of live quarry shooting at European, national and local levels. There are also many wildfowling clubs around the coast of Great Britain, often covering certain estuary areas where wildfowl are found in large numbers.

Waterfowl hunting in Australia

Hunting waterfowl with firearms didn't reach Australia until the 19th century in the southern part of Australia, although aboriginals adjusted their prior methods and started using firearms. Hunting waterfowl was considered sport to Australians in the 19th century up to today. The magpie goose was considered the best table fare of all the birds hunted in Australia, was hunted to near extinction, and is now only allowed to be hunted in the Northern Territory.

In Australia, only three states and one territory permit the hunting of waterfowl using firearms. Hunting with a permit is allowed in the Northern Territory, South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria.[11] Unlike in the U.S., the species a hunter is allowed to kill varies widely between states. There are currently eleven native species of waterfowl that are permitted to be hunted, though no single region permits the hunting of all eleven. In addition to the native species, the Mallard is a feral species in Australia and is permitted to be hunted.[12]

Penalties apply for hunters who kill or injure protected (non-listed) species. Waterfowl that are fully protected in all Australian states and territories and therefore must not be shot include: the Cape Barren goose, Black swan, Freckled duck, Blue-billed duck and Burdekin duck.[12] There are a few species of waterfowl listed as endangered or "vulnerable" under various legislation in Australia.

| Common Name | Species | Northern Territory[13] | South Australia[14] | Victoria[15] | Tasmania[16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chestnut teal | Anas castanea | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Grey teal | Anas gracilis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mallard (introduced species) | Anas platyrhynchos | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Australasian shoveller | Anas rhynchotis | No | No | Yes | No |

| Pacific black duck | Anas superciliosa | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Magpie goose | Anseranas semipalmata | Yes | No | No | No |

| Hardhead | Aythya australis | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Australian wood duck | Chenonetta jubata | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wandering whistling duck | Dendrocygna arcuata | Yes | No | No | No |

| Plumed whistling duck | Dendrocygna eytoni | Yes | No | No | No |

| Pink-eared duck | Malacorhynchus membranaceus | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Mountain duck / Australian shelduck | Tadorna tadornoides | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Waterfowl hunting in Canada

Hunting waterfowl in Canada originated with native Canadians, but was modernized in the late 1700s around the same time the US declared independence. The use of shotguns was introduced by immigrants from Europe. Once it became more modern, rules and regulations were implemented and change yearly due to the flight patterns of birds and endangered species.

Waterfowl is plentiful in Canada, and there is a wide range of birds that are legal to hunt. Geese are a plentiful and popular quarry, and are split into two groups: "dark geese" such as Canada, white front, Brant, and cackling geese, and "white geese", such as snow, blue, and Ross's geese. It is permitted to hunt for ducks such as mallards, blue and green-wing teal, and Northern pintails. One may also hunt ducks like redheads, blackducks, canvasbacks, buffleheads, wood ducks, ringneck or ring-billed ducks, greater or lesser scaup, common goldeneye, cinnamon teal, and American widgeon. Other fowl such as coot, snipe, woodcock, and sandhill cranes also generally fall under "waterfowl" legislation and any related permit and/or license systems.[17] Additional provincial restrictions may exist for specific species beyond what is restricted by federal legislation.

To hunt waterfowl in Canada, one must first obtain a valid Canada Migratory Game Bird Hunting Permit with a Wildlife Habitat Conservation stamp affixed to or printed on the permit, as well as any additional licenses and certificates which may be required at the provincial level. There is also a bag limit and a possession limit, based on species of group. The bag limit is the total number of individuals of a specific species or group that one is allowed to harvest within a given hunting day (generally considered to run 30 minutes after sunrise to 30 minutes before sunset), and the possession limit is how many birds one may legally have has in one's possession including those in one's game bag, vehicle, at home, etc. For example, if there is a bag limit of 8 and a possession limit of 24, you may harvest 8 individuals in any single day, but you may only possess a total of 24 individuals at any one time. It is important to stay current on regulations as they are frequently updated based on target species population trends. This close monitoring and regulation adjustment ensures the sustainability of waterfowl hunting in Canada for many generations to come by supporting healthy populations of desirable game species and their habitats.[18]

Regulations, sportsmanship, and safety

Waterfowl hunting is highly regulated in most western countries. Hunters are required to obtain a hunting license and face strict limits on the number of birds that can be taken in a day (bag limits), and the total number of birds a hunter can possess (possession limits).

There were no regulations on waterfowl hunting from when the Paleo Indians arrived in North America to the early 20th century. In the early 20th century large bore shotguns and rifles were used. Traps were used. Live decoys were used in front of blinds, as well as shotguns holding many shells. Hunting was done throughout the year. In 1913 the United States Congress passed the Weeks–McLean Act regulating waterfowl hunting; however, the states were successful in arguing that the constitution gave no such regulatory power to the federal government, and the statute was struck down. In response, the United States negotiated the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 with the United Kingdom (which at the time was largely responsible for Canada's foreign affairs) covering the same substance, but would be constitutional because of the Supremacy Clause. The treaty was upheld by the Supreme Court in Missouri v. Holland.

In the United States, hunters must also purchase a federal duck stamp and often a state stamp. It is illegal to shoot ducks from a motor vehicle or a moving boat. Shooting sitting or swimming ducks is considered unsportsmanlike by some and possibly unsafe. Many practices that were once common in commercial duck hunting before the start of the 20th century, including laying baits such as corn, use of live ducks as "decoys," and use of guns larger than a 10-gauge, are now prohibited.[19] In most areas, shotguns that can hold more than three shells must be modified to reduce their magazine size. A wooden plug is installed in the hollow magazine of the shotgun. Legal hunting is limited to a set time period (or "season"), which generally extends from fall to early winter, while birds are migrating south.[20]

The Conservation Order established by the USF&WS allows for hunting snow geese in March and April. The reason for this is that snow geese populations have become so large that more hunting is needed to control their populations, as they are destroying their habitat. Shotguns can be loaded to full capacity for hunting these geese.

It is also considered good sportsmanship to make every possible attempt to retrieve dead or injured waterfowl the hunter has shot (In the Australian state of Victoria it is required by law). Birds are shot within range to prevent cripples. Shooting before birds are within range is also considered poor sportsmanship, as this often merely injures the birds and may drive them away before other hunters can fire.

Many provinces in Canada and all states require hunters, including waterfowl hunters, to complete hunter safety courses before they can obtain a license.[21] Waterfowl hunters fire short-range shotgun rounds into the air over often deserted bodies of water, so accidental injuries are rarer than in other hunting activities such as big game or deer hunting.

Hunting areas

.jpg.webp)

All states except Hawaii have public land for waterfowl hunting. Some states might refer to them as fish and game lands or Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs). Every state's DNR has a website, and each has a link to their licenses and regulations and WMAs, as well as information on various draw and public hunts. Some states call them fish and wildlife management areas. These are lands purchased from hunting license revenue. Water in bays or ocean are open area to hunting, as no one can own these areas, although some counties in North Carolina and Virginia still allow a limited number of Registered Blinds in public waters of certain coastal counties. The Mississippi Flyway is a very famous waterfowling community. The Central Flyway has the highest numbers of waterfowl migrating south from Canada in the Great Southern Migration. The Pacific Flyway is an exceptional hunting area for migratory waterfowl today, although their WMAs can be quite crowded from Washington State all the way south to California rice fields which used to see Hollywood's great hunters flock to Tulle Lake, and Sacramento private duck hunting clubs.

The problem for the average waterfowler is getting access to the ocean, bay, marsh, or lake to hunt public access waters. Hunters usually need large boats, and motors to travel safely to and in these areas. Many people will set up hunting blinds on the shoreline of water unless it is private property. Many states across the United States are not allowing the building of hunting blinds on any public waters. Such action therefore allows more use of boat blinds, and therefore no permanent water hazards of blinds in public waters such as lakes, bays or sounds allows all waterfowl hunters to hunt all public waters. This can be very successful if they know how to use a duck call, and proper use of decoy placement and wind direction, and can call ducks in towards their decoys. Most sportsmen know to stay at least 500 yards from anyone else that may be hunting nearby them in public waters. More waterfowlers today should learn from their elders the importance of "ethical sportsmanship", whenever gunning on public waters hunting ducks and geese today and in the future.

Flyways

In North America, the routes used by migratory waterfowl are generally divided into four broad geographical paths known as flyways. Each flyway is characterized by a different composition of species and habitat. The U.S. fish and wildlife service established the flyways to help with the management of migratory birds. They studied all migratory birds and established the Mississippi, Atlantic, Mountain, and Pacific flyway, all holding different species of migratory birds.

Mississippi flyway

The Mississippi flyway is a migration route used by waterfowl to travel from central Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, flying along the route of the Mississippi River and its tributaries. The Mississippi flyway is one of the of the most popular flyways to hunt in North America. Along with being popular its very abundant in many species of migrating waterfowl. For the dabbling waterfowl it has the American Wigeon, blue-winged teal, green-winged teal, mallard, mottled duck, northern pintail, northern shoveler, gadwall, and the wood duck. The flyway has an abundance of diving ducks as well such as the bufflehead, canvasback, hooded merganser, redhead, and ring neck. the flyway i\s also home to a large amount of geese such as the, Canda goose, blue goose, cackling goose, ross goose, sn0w goose, and the white-fronted goose.

In the Midwest and central United States, wildfowl hunting generally occurs on lakes, marshes, swamps, or rivers where ducks and geese land during their migration. Cornfields and rice paddies are also common hunting grounds, since geese and ducks often feed on the grain that remains in the field after harvest. In some areas, farmers rent or lease hunting rights. Some farmers or hunters form hunt clubs, which can cover thousands of acres and have resort-like amenities, or be as simple as a shallow pit blind dug into a field. On the East and West Coast of America and many parts of Europe, waterfowl hunters often focus on the seashore.

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service maintains millions of acres as National Wildlife Refuges open to public hunting. All states have public hunting and fishing areas. States publish maps of these areas.

Atlantic flyway

The Atlantic Flyway is a migration route used by waterfowl flying from northern Quebec to Florida in the autumn and back in the springtime. This is where duck hunting first started some of the largest and grandest waterfowl hunting clubs and clubhouses in North America. Look at photos of the "Whalehead Club in the Outer Banks of North Carolina" which is no longer a hunting club, but is a historical building today, built in the grand style of the gilded age of water fowling. North Carolina waterfowl guide and writer Joe Guide states, "some of the greatest and grandest of Waterfowl Clubs along the famous Atlantic flyway developed following the Civil War era, and the largest ones were financed by Northerners loaded with money due to the great industrial revolution period beginning around the mid 1870s—and most of the grand waterfowl clubs ended due to the great depression years due to economic conditions. It might surprise you that a majority of the grand Atlantic Seaboard Waterfowl Hunt Clubs did not have southerners as "members" until well into the 1950s, however, they all used locals as caretakers, guides, paddlers, and cooks". Diver hunting is the major waterfowl activity along the coastal regions of the Atlantic, however, local populations of greater snow geese seem to be increasing in number, as they have started breeding with lesser snow geese and their migration range is ever increasing.

.jpg.webp)

Ducks and geese are born in the tundra of Quebec, and fly south in autumn to Chesapeake Bay and Virginia's famous Back Bay, and the James River, and then move southward through North and South Carolina, Georgia and Florida for the winter. Northeast and northwest Florida get a great number of teal and divers as the winter progresses. In the northeastern states the Saint Lawrence River, the coast of Maine, Long island harbors, Barnegat Bay, Great Egg Harbor, Little Egg Harbor, Absecon Bay, Delaware Bay, Chesapeake Bay, Virginia's Eastern Shore and Back Bays saw presidents and captains of great industry spend part of their winters at their wildfowling clubs. North Carolina's Outer Banks, and the Core and Pamlico Sounds have been known for centuries for great waterfowl hunting drawing people from throughout the big cities of the northeastern states. In South Carolina there was Georgetown's and Charleston's old rice fields, and backcountry marshes and freshwater rivers and lakes that continued to draw ducks in great numbers until the Santee National Wildlife Refuge stopped feeding the ducks in the winter months of the 1980s due to the economy and changes in National Wildlife Refuge policy across the nation. In the 1960s to the mid-1980s the upper Santee swamp's upper Lake Marion region used to winter over 150,000 mallards each and every winter's duck count. The Atlantic flyway holds a large number of migrating waterfowl. for dabbling ducks holds a bunch of the same birds as the Mississippi fly way with them being neighboring flyway geese are also the same, but what the Atlantic flyway has that the Mississippi flyway doesn't have is the sea ducks and geese. Such as atlantic brant, common eider, golden eye, surf scoter, common eider, white winged scoter.

In the Chesapeake Bay area well into the 1930s one of the biggest threats to waterfowl was "local poachers" using flat boat boats, mounting huge 12 foot black powder swivel guns. Most of these ancient weapons have been confiscated and are in museums, although a few families have hidden theirs as family keepsakes.[22]

Mountain (Central) Flyway

The Rocky Mountain Flyway is used by waterfowl of that region to fly from Alberta and Saskatchewan Canada to Texas, the Gulf Coast, and western Mexico. the central flyway is one of the larger of the flyways. holding a majority of the migrating waterfowl species that can be found in the Mississippi flyway and the Atlantic and pacific flyway. the central flyway doesn't have sea ducks.

The Pacific flyway is a migration route from central Alaska to southern Mexico. It is used by nearly all waterfowl species in that region. The pacific flyway is home to a large abundance of north American waterfowl. you can find almost all waterfowl except the black duck, and the pacific flyway is home to the pacific brant. This is the bird that holds the record for the longest migration without stopping.

Due to extensive market hunting from the 18th century to the early 20th century, waterfowl populations dropped drastically. In the 1930s there was a severe drought, in which waterfowl populations declined severely.

Waterfowl are indigenous to marsh and wetland areas, which are shrinking at alarming rates due to the drought and farmers draining wetland areas to plant crops. Wetland conservation and restoration is critical for the continuance of waterfowl hunting. Organizations such as Ducks Unlimited are making a concerted effort to maintain and expand waterfowl and marshland conservation to ensure safety and expansion of the sport. Ducks Unlimited buys land or converts land into waterfowl habitat. Ducks Unlimited started in 1937 in Sullivan County, New York when a hunter went hunting along a river and could not find any wood ducks. This hunter and others formed Ducks Unlimited. Now Ducks Unlimited has thousands of members that donate millions of dollars for buying waterfowl habitat in the United States, Canada and Mexico. Ducks Unlimited has many dinners and other fund raisers throughout the year in each state.

See also

References

- ↑ David, Arlette (2014). "Hoopoes and Acacias: Decoding an Ancient Egyptian Funerary Scene". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 73 (2): 235–252. doi:10.1086/677251. S2CID 164075553.

- ↑ Baldassarre, Guy A.; Bolen, Eric G.; Saunders, D. Andrew (1994). Waterfowl Ecology and Management. New York: Wiley. pp. 3–6. ISBN 0-471-59770-8.

- ↑ The diary of Colonel Peter Hawker, (Volume I) 1802-1853

- ↑ "News Release: Aug. 10, 2007: New Way to Buy Federal Duck Stamps: The E-Duck Stamp - TPWD".

- ↑ "Artistic License- The Duck Stamp Story." Smithsonian National Postal Museum.

- ↑ "DUCK STAMP NEWS". Archived from the original on 2008-04-20.

- ↑ Sanderson, Glen C.; Bellrose, Frank C. (1986). "A Review of the Problem of Lead Poisoning in Waterfowl". Special Publication. Champaign, Illinois. Archived from the original on April 22, 1999.

- ↑ Scheuhammer, A. M.; Norris, S. L. (1996). "The ecotoxicology of lead shot and lead fishing weights". Ecotoxicology. 5 (5): 279–295. doi:10.1007/BF00119051. PMID 24193869. S2CID 40092400.

- ↑ "Nicaragua Bird Hunting".

- ↑ Ratcliffe, Roger (6 October 2006). "Blast from the past". The Yorkshire Post. Johnston Publishing Ltd. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (9 December 2019). "Duck - Game Management Authority". www.gma.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- 1 2 "Know your birds - SSAA". ssaa.org.au. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ↑ Government, Northern Territory (2019-08-22). "Magpie geese and waterfowl season dates". nt.gov.au. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ↑ "Duck Hunting". www.environment.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ↑ Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (9 December 2019). "Game duck species - Game Management Authority". www.gma.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ↑ "Species of Game | Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Tasmania". dpipwe.tas.gov.au. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ↑ "Conserving Canada's Wetlands | Ducks Unlimited Canada".

- ↑ "Migratory Game Bird Hunting Permit". September 2011.

- ↑ State of California. "Selected 2006 Waterfowl Hunting Regulations."

- ↑ TPWD:2006 2006-2007 Texas Hunting Season Dates, Grouped by Animal

- ↑ "Hunter Education Requirements in the United States and Canada — Texas Parks & Wildlife Department".

- ↑ "Poaching Made Big Business", October 1933, Popular Science middle of page

External links

- Flyways.us – United States Fish & Wildlife Service, Flyway Councils, waterfowl hunting management in North America

- Delta Waterfowl Foundation – Waterfowl hunting

- Ducks Unlimited – Hunting and Wetlands and Waterfowl Conservation

- The Book of Duck Decoys – Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey, 1886 (full text)

- British Duck Decoys of To-Day, 1918 – Joseph Whitaker (full text)

- Midwest Decoy Collectors Association – The de facto international collectors group

- "Hide And Seek With The Mallards", October 1931, Popular Mechanics

- British Association for Shooting and Conservation – Covering wildfowling in the UK

- Duckr – Application devoted to identifying waterfowl

- Waterfowl Craft – Hub dedicated to bringing awareness to Waterfowl Hunting