Duchy of Normandy | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 911–1259 | |||||||||||

Heraldic flag of Normandy

| |||||||||||

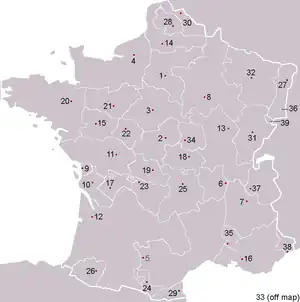

![Normandy's historical[when?] borders in the northwest of France and the Channel Islands](../I/Cartenormandie2.PNG.webp) Normandy's historical borders in the northwest of France and the Channel Islands | |||||||||||

| Status | Vassal state of West Francia (911-987) Vassal state of the Kingdom of France (987-1066) Dynastic union with the Kingdom of England (1066-1204) Disputed between England and France (1204-1259) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Rouen | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Old Norman • Medieval Latin | ||||||||||

| Minority languages | Old Norse (till early-mid 11th century) | ||||||||||

| Religion | Norse religion Roman Catholicism | ||||||||||

| Duke of Normandy | |||||||||||

• 911–927 | Rollo (first) | ||||||||||

• 1035–1087 | William the Conqueror | ||||||||||

• 1144–1150 | Geoffrey Plantagenet | ||||||||||

• 1199–1204 | John (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

| 911 | |||||||||||

| 1066 | |||||||||||

• Geoffrey Plantagenet inherits the Duchy of Normandy | 1144 | ||||||||||

• Continental Normandy conquered by French Crown | 1204 | ||||||||||

| 1259 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Denier (Rouen penny) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | France | ||||||||||

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a result of the Norman conquest of England, the dukes of Normandy were usually also kings of England, the only exceptions being Dukes Robert Curthose (1087–1106), Geoffrey Plantagenet (1144–1150), and Henry II (1150–1152), who became king of England in 1154.

In 1202, Philip II of France declared Normandy forfeit to him and seized it by force of arms in 1204. It remained disputed territory until the Treaty of Paris of 1259, when the English sovereign ceded his claim except for the Channel Islands; i.e., the Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey, and their dependencies (including Sark).

In the Kingdom of France, the duchy was occasionally set apart as an appanage to be ruled by a member of the royal family. After 1469, however, it was permanently united to the royal domain, although the title was occasionally conferred as an honorific upon junior members of the royal family. The last French duke of Normandy in this sense was Louis-Charles, duke from 1785 to 1792.

The title "Duke of Normandy" continues to be used in an informal manner in the Channel Islands, to refer to the monarch of the United Kingdom.

History

Origins

The first Viking attack up the Seine river took place in 820. By 911, the area had been raided many times and there were even small Viking settlements on the lower Seine. The text of the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte has not survived. It is only known through the historian Dudo of Saint-Quentin, who was writing a century after the event. The exact date of the treaty is unknown, but it was likely in the autumn of 911. By the agreement, Charles III, king of the West Franks, granted to the Viking leader Rollo some lands along the lower Seine that were apparently already under Danish control. Whether Rollo himself was a Dane or a Norwegian is not known. For his part, Rollo agreed to defend the territory from other Vikings and that he and his men would convert to Christianity.[1] Rollo's decision to convert and come to terms with the Franks came in the aftermath of his defeat at the battle of Chartres by Dukes Richard of Burgundy and Robert of Neustria (the future Robert I of France) earlier in 911.[2]

The territory ceded to Rollo comprised the pagi of the Caux, Évrecin, Roumois and Talou. This was territory formerly known as the county of Rouen, and which would become Upper Normandy. A royal diploma of 918 confirms the donation of 911, using the verb adnuo ("I grant"). There is no evidence that Rollo owed any service or oath to the king for his lands, nor that there were any legal means for the king to take them back: they were granted outright.[1] Likewise, Rollo does not seem to have been created a count or given comital authority, but later sagas refer to him as Rúðujarl (earl of Rouen).[3]

In 924, King Radulf extended Rollo's county westward up to the river Vire, including the Bessin, where some Danes from England had settled not long before. In 933, King Radulf granted the Avranchin and Cotentin to Rollo's son and successor, William Longsword. These areas had been previously under Breton rule. The northern Cotentin had been settled by Norwegians coming from the region of the Irish Sea. There was initially much hostility between these Norwegian settlers and their new Danish overlords. These expansions brought the boundaries of Normandy roughly in line with those of the ecclesiastical province of Rouen.[1]

The Norman polity had to contend with the Frankish and Breton systems of power that already existed in Normandy. In the early 10th century, Normandy was not a political or monetary unit. According to many academics, "the formation of a new aristocracy, monastic reform, episcopal revival, written bureaucracy, saints’ cults – with necessarily different timelines" were as important if not more than the ducal narrative espoused by Dudo. The formation of the Norman state also coincided with the creation of an origin myth for the Norman ducal family through Dudo, such as Rollo being compared to a "good pagan" like the Trojan hero Aeneas. Through this narrative, the Normans were assimilated closer to the Frankish core as they moved away from their pagan Scandinavian origins.[4][5]

Norse settlement

There were two distinct patterns of Norse settlement in the duchy. In the Danish area in the Roumois and the Caux, settlers intermingled with the indigenous Gallo-Romance-speaking population. Rollo shared out the large estates with his companions and gave agricultural land to his other followers. Danish settlers cleared their own land to farm it, and there was no segregation of populations.[1]

In the northern Cotentin on the other hand, the population was purely Norwegian. Coastal features bore Norse names as did the three pagi of Haga, Sarnes and Helganes (as late as 1027). The Norwegians may even have set up a þing, an assembly of all free men, whose meeting place may be preserved in the name of Le Tingland.[1]

Within a few generations of the founding of Normandy in 911, however, the Scandinavian settlers had intermarried with the natives and adopted much of their culture. But in 911, Normandy was not a political nor monetary unit. Frankish culture remained dominant and according to some scholars, 10th century Normandy was characterized by a diverse Scandinavian population interacting with the "local Frankish matrix" that existed in the region. In the end, the Normans stressed assimilation with the local population.[4] In the 11th century, the anonymous author of the Miracles of Saint Wulfram referred to the formation of a Norman identity as "shaping [of] all races into one single people".[1]

According to some historians, the idea of "Norman" as a political identity was a deliberate creation of the court of Richard I in the 960s as a way to "create a powerful if rather incoherent sense of group solidarity to galvanize the duchy's disparate elites around the duke".[6]

Norman rule

Starting with Rollo, Normandy was ruled by an enduring and long-lived Viking dynasty. Illegitimacy was not a bar to succession and three of the first six rulers of Normandy were illegitimate sons of concubines. Rollo's successor, William Longsword, managed in expanding his domain and came into conflict with Arnulf of Flanders, who had him assassinated in 942.[7] This led to a crisis in Normandy, with a minor succeeding as Richard I, and also led to a temporary revival of Norse paganism in Normandy.[8] Richard I's son, Richard II, was the first to be styled duke of Normandy, the ducal title becoming established between 987 and 1006.[9]

The Norman dukes created the most powerful, consolidated duchy in Western Europe between the years 980, when the dukes helped place Hugh Capet on the French throne, and 1050.[10] Scholarly churchmen were brought into Normandy from the Rhineland, and they built and endowed monasteries and supported monastic schools, thus helping to integrate distant territories into a wider framework.[11] The dukes imposed heavy feudal burdens on the ecclesiastical fiefs, which supplied the armed knights that enabled the dukes to control the restive lay lords but whose bastards could not inherit. By the mid-11th century the Duke of Normandy could count on more than 300 armed and mounted knights from his ecclesiastical vassals alone.[10] By the 1020s the dukes were able to impose vassalage on the lay nobility as well. Until Richard II, the Norman rulers did not hesitate to call Viking mercenaries for help to get rid of their enemies around Normandy, such as the king of the Franks himself. Olaf Haraldsson crossed the Channel in such circumstances to support Richard II in the conflict against the count of Chartres and was baptized in Rouen in 1014.[12]

In 1066, Duke William defeated Harold II of England at the Battle of Hastings and was subsequently crowned King of England, through the Norman conquest of England.[13] Anglo-Norman and French relations became complicated after the Norman Conquest. The Norman dukes retained control of their holdings in Normandy as vassals owing fealty to the King of France, but they were his equals as kings of England. Serfdom was outlawed around 1100.[14]

From 1154 until 1214, with the creation of the Angevin Empire, the Angevin kings of England controlled half of France and all of England, dwarfing the power of the French king, yet the Angevins were still de jure French vassals.[15]

The Duchy remained part of the Anglo-Norman realm until 1204,[16] when Philip II of France conquered the continental lands of the Duchy, which became part of the royal domain. The English sovereigns continued to claim them until the Treaty of Paris (1259) but in fact kept only the Channel Islands.[17] Having little confidence in the loyalty of the Normans, Philip installed French administrators and built a powerful fortress, the Château de Rouen, as a symbol of royal power.[18]

French appanage

Although within the royal demesne, Normandy retained some specificity. Norman law continued to serve as the basis for court decisions. In 1315, faced with the constant encroachments of royal power on the liberties of Normandy, the barons and towns pressed the Norman Charter on the king. This document did not provide autonomy to the province but protected it against arbitrary royal acts. The judgments of the Exchequer, the main court of Normandy, were declared final. This meant that Paris could not reverse a judgment of Rouen.[19] Another important concession was that the King of France could not raise a new tax without the consent of the Normans. However the charter, granted at a time when royal authority was faltering, was violated several times thereafter when the monarchy had regained its power.[20]

The Duchy of Normandy survived mainly by the intermittent installation of a duke. In practice, the King of France sometimes gave that portion of his kingdom to a close member of his family, who then did homage to the king. Philippe VI made Jean, his eldest son and heir to his throne, the Duke of Normandy. In turn, Jean II appointed his heir, Charles.[21]

In 1465, Louis XI was forced by the League of the Public Weal to cede the duchy to his eighteen-year-old brother, Charles de Valois.[22] This concession was a problem for the king since Charles was the puppet of the king's enemies. Normandy could thus serve as a basis for rebellion against the royal power. In 1469, therefore, Louis XI convinced his brother under duress to exchange Normandy for the Duchy of Guyenne (Aquitaine).[23] Finally, at the request of the cowed Estates of Normandy and to signify that the duchy would not be ceded again, at a session of the Norman Exchequer on 9 November 1469 the ducal ring was placed on an anvil and smashed.[24] Philippe de Commynes expressed what was probably a common Norman thought of the time: "It has always seemed good to the Normans and still does that their great duchy really should require a duke" (A tousjours bien semblé aux Normands et faict encores que si grand duchié comme la leur requiert bien un duc).[25]

Dauphin Louis Charles, the second son of Louis XVI, was again given the nominal title of 'Duke of Normandy' before the death of his elder brother in 1789.[26]

Modern usage

In the Channel Islands, the British monarch is known informally as the "Duke of Normandy", irrespective of whether or not the holder is male (as in the case of Queen Elizabeth II who was known by this title).[27] The Channel Islands are the last remaining part of the former Duchy of Normandy to remain under the rule of the British monarch. Although the English monarchy relinquished claims to continental Normandy and other French claims in 1259 (in the Treaty of Paris), the Channel Islands (except for Chausey under French sovereignty) remain Crown dependencies of the British throne.

In the islanders' loyal toast, they say, "The Duke of Normandy, our King", or "The King, our Duke", "L'Rouai, nouotre Duc" or "L'Roué, note Du" in Norman (Jèrriais and Guernésiais respectively), or "Le Roi, notre Duc" in Standard French, rather than simply "The King", as is the practice in the United Kingdom.[28][29]

Queen Elizabeth II is often referred to by her traditional and conventional title of Duke of Normandy. However ... she is not the Duke in a constitutional capacity and instead governs in her right as Queen ... This notwithstanding, it is a matter of local pride for monarchists to treat the situation otherwise: the Loyal Toast at formal dinners is to "The Queen, our Duke" rather than "Her Majesty, the Queen" as in the UK.[29]

The title 'Duke of Normandy' is not used in formal government publications, and, as a matter of Channel Islands law, does not exist.[30][29]

The British historian Ben Pimlott noted that while Queen Elizabeth II was on a visit to mainland Normandy in May 1967, French locals began to doff their hats and shout "Vive la Duchesse!", to which the Queen supposedly replied "Well, I am the Duke of Normandy!"[31]

Rulers

Dukes

Governors

Below is a list of the governors of the Duchy of Normandy during its time as a French province.[32]

- 9 May 1661 – 1726: Charles François Frédéric de Montmorency, Duke of Piney

- 1726 – 18 May 1764: Marshal of France Charles François Frédéric de Montmorency II, Duke of Piney

- 15 June 1764 – 1775: Marshal of France Anne-Pierre, Duke of Harcourt

- 17 September 1775 – 1 January 1791: François Henri, Duke of Harcourt

Law

There are traces of Scandinavian law in the customary laws of Normandy, which were first written down in the 13th century.[19] A charter of 1050, listing several pleas before Duke William II, refers to the penalty of banishment as ullac (from Old Norse útlagr). The word was still current in the 12th century, when it was used in the Roman de Rou.[33] Marriage more danico ("in the Danish manner"), that is, without any ecclesiastical ceremony in accordance with old Norse custom, was recognised as legal in Normandy and in the Norman church. The first three dukes of Normandy all practised it.[1]

Scandinavian influence is especially apparent in laws relating to waters. The duke possessed the droit de varech (from Old Danish vrek), the right to all shipwrecks.[34] He also had a monopoly on whale and sturgeon. A similar monopoly belonged to the Danish king in the Jutlandic law of 1241. Remarkably, whale (including dolphins) and sturgeon still belong to the monarch in the United Kingdom in the twenty-first century, as royal fish.[35] The Norman Latin terms for whalers (valmanni, from hvalmenn) and whaling station (valseta, from hvalmannasetr) both derive from Old Norse. Likewise, fishing in Normandy seems to have come under Scandinavian rules. A charter of 1030 uses the term fisigardum (from Old Norse fiskigarðr) for "fisheries", a term also found in the Scanian law of c. 1210.[1]

There is no surviving reference to the hirð or the leiðangr in Normandy, but the latter probably existed. The surname Huscaille, first attested in 1263, probably derives from húskarl, but is late evidence for the existence of a hirð in the 10th century.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Renaud, Jean (2008). Brink, Stefan (ed.). The Duchy of Normandy. Routledge. pp. 453–457.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Lake, Justin (2013). Richer of Saint-Rémi: The Methods and Mentality of a Tenth-Century Historian. Catholic University of America Press. p. 101.

- ↑ Helmerichs, Robert (1997). "Princeps, Comes, Dux Normannorum: Early Rollonid Designators and Their Significance"". The Haskins Society Journal. 9: 57–77.

- 1 2 Abrams, Lesley (January 2013). "Early Normandy". Anglo-Norman Studies: 45–64. doi:10.1017/9781782041085.005. ISBN 9781782041085.

- ↑ Miller, Aron. "Scandinavian Origins through Christian Eyes: A Comparative Study of the History of the Normans and the Russian Primary Chronicle". repository.stcloudstate.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ↑ McNair, Fraser (2015). "The politics of being Norman in the reign of Richard the Fearless, Duke of Normandy (r. 942–996)" (PDF). Early Medieval Europe. 23 (3): 308–328. doi:10.1111/emed.12106. ISSN 1468-0254.

- ↑ Thorpe, Benjamin (1857). A History of England Under the Norman Kings: Or, from the Battle of Hastings to the Accession of the House of Plantagenet: To Which Is Prefixed an Epitome of the Early History of Normandy. London: John Russel Smith. p. 24.

- ↑ Bradbury, Jim (2007). The Capetians: Kings of France 987-1328. London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 9780826435149.

- ↑ Rowley, Trevor (2009-07-20). Normans. The History Press. ISBN 9780750951357.

- 1 2 Cantor, Norman F. (1993) [1963]. The Civilization of the Middle Ages: A Completely Revised and Expanded Edition of Medieval History. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 206–210. ISBN 9780060170332.

- ↑ Potts, Cassandra (1997). Monastic Revival and Regional Identity in Early Normandy. Suffolk, UK & Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 70–71. ISBN 9780851157023.

- ↑ "Olav Haraldsson – Olav the Stout – Olav the Saint". The Viking Network. 25 June 2015. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- ↑ Rex, Peter (2012) [2008]. 1066: A New History of the Norman Conquest. Stroud, UK: Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445608839.

- ↑ Sept essais sur des Aspects de la société et de l'économie dans la Normandie médiévale (Xe – XIIIe siècles) Lucien Musset, Jean-Michel Bouvris, Véronique Gazeau -Cahier des Annales de Normandie- 1988, Volume 22, Issue 22, pp. 3–140

- ↑ Turner, Ralph V. (1995-02-01). "The Problem of Survival for the Angevin "Empire": Henry II's and His Sons' Vision versus Late Twelfth-Century Realities". The American Historical Review. 100 (1): 78–96. doi:10.1086/ahr/100.1.78. ISSN 0002-8762.

- ↑ Harper-Bill, Christopher; Houts, Elisabeth Van (2007). A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World. Suffolk, UK & Rochester, New York: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 63. ISBN 9781843833413.

- ↑ Powicke, Frederick Maurice (1999) [1913]. The Loss of Normandy, 1189-1204: Studies in the History of the Angevin Empire. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. p. 138. ISBN 9780719057403.

- ↑ Baldwin, John W. (1986). The Government of Philip Augustus: Foundations of French Royal Power in the Middle Ages. Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press. pp. 220–230. ISBN 9780520911116.; "Castles.nl - Joan of Arc Tower". www.castles.nl. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- 1 2 Vincent, Nicholas (2015). "Magna Carta (1215) and the Charte aux Normands (1315): Some Anglo-Norman Connections and Correspondences" (PDF). Jersey and Guernsey Law Review. 2: 189–197.

- ↑ Contamine, Philippe (1994). "The Norman "Nation" and the French "Nation" in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries". In Bates, David; Curry, Anne (eds.). England and Normandy in the Middle Ages. London, UK & Rio Grand, OH: A&C Black. pp. 224–225. ISBN 9780826443090.

- ↑ Reuter, Timothy (2000). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 6, C.1300-c.1415. Vol. VI. Cambridge, New York and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. p. 409. ISBN 9780521362900.; "Normandy (Traditional province, France)". www.crwflags.com. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- ↑ Guenee, Bernard; Guenée, Bernard (1991) [1987]. Between Church and State: The Lives of Four French Prelates in the Late Middle Ages. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. pp. 332–333. ISBN 9780226310329.; Smedley, Edward (1836). The History of France: From the Final Partition of the Empire of Charlemagne, A.D. 843, to the Peace of Cambray, A.D. 1529. London: Baldwin. pp. 388–389.

- ↑ Grove, Joseph (1742). The History of the Life and Times of Cardinal Wolsey, Prime Minister to King Henry VIII, Vol. 1: I. Of His Birth, and the Various Steps He Took to Attain Preferment, Connected With Affairs, Both Foreign and Domestick, From the Death of Edward IV. To He End of the Reign of Henry VII. London: J. Purser. p. 57.

- ↑ Michelet, Jules (1845). History of France. Translated by Smith, G. H. London: Whittaker and Co. p. 309.

- ↑ Contamine (1994), p. 233.

- ↑ "Reviewed Works: Louis XVII.: sa Vie, son Agonie, sa Mort; Captivité de la Famille Royale au Temple; Ouvrage enrichi d'Autographes, de Portraits, et de Plans. 2 vols. 8vo by M. A. de Beauchesne; Filia Dolorosa : Memoirs of MARIE THÉRÈSE CHARLOTTE, Duchess of Angoulême, the Last of the Dauphines. 2 vols. 8vo by Mrs. Romer; An Abridged Account of the Misfortunes of the Dauphin, followed by some Documents in Support of the Facts related by the Prince; with a Supplement by C. G. Percival". The North American Review. 78 (162): 105–150. January 1854. JSTOR 40794680.

- ↑ "Crown Dependencies". The Royal Household. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ↑ "The Loyal Toast". Debrett's. 2016. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

In Jersey the toast of 'The Queen, our Duke' (i.e. Duke of Normandy) is local and unofficial, and used when only islanders are present. This toast is not used in the other Channel Islands.

- 1 2 3 The Channel Islands, p. 11, at Google Books

- ↑ Matthews, Paul (1999). "Lé Rouai, Nouot' Duc" (PDF). Jersey and Guernsey Law Review. 1999 (2).

- ↑ The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy, p. 314, at Google Books

- ↑ "Provinces of France to 1791". www.worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ↑ Battail, Marianne; Battail, Jean-François (1993). Une amitié millénaire: les relations entre la France et la Suède à travers les âges (in French). Paris: Editions Beauchesne. p. 61. ISBN 9782701012810.

- ↑ "Varech coutume de Normandie | Varech en Manche|". Le Petit Manchot - histoire patrimoine personnage (in French). Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- ↑ Johnson, Dennis (2014-05-21). "Palace prevails on a 'fish royal' supper: from the archive, 21 May 1980". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

.svg.png.webp)