Netherlands Antilles | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1954–2010 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: Latin: Libertate unanimus Dutch: In vrijheid verenigd "Unified in freedom" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: "Wilhelmus" (1954–1964) "Tera di solo y suave biento" (1964–2000) "Anthem without a title" (2000–2010) | |||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Willemstad | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Dutch English Papiamento[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Netherlands Antillean | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Monarchs | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1954–1980 | Juliana | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1980–2010 | Beatrix | ||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1951–1956 (first) | Teun Struycken | ||||||||||||||||||

• 2002–2010 (last) | Frits Goedgedrag | ||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1951–1954 (first) | Moises Frumencio da Costa Gomez | ||||||||||||||||||

• 2006–2010 (last) | Emily de Jongh-Elhage | ||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament of the Netherlands Antilles | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

| 15 December 1954 | |||||||||||||||||||

• Secession of Aruba | 1 January 1986 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 10 October 2010 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Netherlands Antillean guilder | ||||||||||||||||||

| Calling code | 599 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .an | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

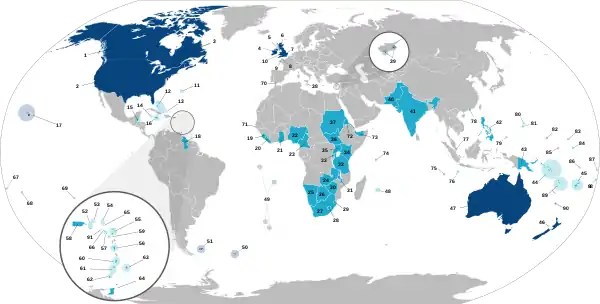

The Netherlands Antilles (Dutch: Nederlandse Antillen, pronounced [ˈneːdərlɑntsə ʔɑnˈtɪlə(n)] ⓘ; Papiamento: Antia Hulandes)[2] was a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The country consisted of several island territories located in the Caribbean Sea. The islands were also informally known as the Dutch Antilles.[3] The country came into being in 1954 as the autonomous successor of the Dutch colony of Curaçao and Dependencies. The Antilles were dissolved in 2010. The Dutch colony of Surinam, although it was relatively close by on the continent of South America, did not become part of the Netherlands Antilles but became a separate autonomous country in 1954. All the island territories that belonged to the Netherlands Antilles remain part of the kingdom today, although the legal status of each differs. As a group they are still commonly called the Dutch Caribbean, regardless of their legal status.[4] People from this former territory continue to be called Antilleans (Antillianen) in the Netherlands.[5]

Geographical grouping

The islands of the Netherlands Antilles are all part of the Lesser Antilles island chain. Within this group, the country was spread over two smaller island groups: a northern group (part of Leeward Islands) and a western group (part of the Leeward Antilles). No part of the country was in the southern Windward Islands.

Islands located in the Leeward Islands

This island subregion was located in the eastern Caribbean Sea, to the east of Puerto Rico. It consisted of three islands, collectively known as the "SSS Islands":

Saba

Saba Sint Eustatius

Sint Eustatius Sint Maarten (the southern part of the island of Saint Martin)

Sint Maarten (the southern part of the island of Saint Martin)

The islands are located approximately 800–900 kilometers (430–490 nautical miles; 500–560 miles) northeast of the ABC Islands.

Islands located in the Leeward Antilles

This island subregion was located in the southern Caribbean Sea off the north coast of Venezuela. There were three islands collectively known as the "ABC Islands":

Aruba (until 1 January 1986)

Aruba (until 1 January 1986) Bonaire including an islet called Klein Bonaire ("Little Bonaire")

Bonaire including an islet called Klein Bonaire ("Little Bonaire") Curaçao, including an islet called Klein Curaçao ("Little Curaçao")

Curaçao, including an islet called Klein Curaçao ("Little Curaçao")

Climate

The Netherlands Antilles have a tropical trade-wind climate, with hot weather all year round. The Leeward islands are subject to hurricanes in the summer months, while those islands located in the Leeward Antilles are warmer and drier.

History

Spanish explorers discovered both the leeward (Alonso de Ojeda, 1499) and windward (Christopher Columbus, 1493) island groups in the late 16th century. However, the Spanish Crown only founded settlements in the Leeward Islands. In the 17th century the islands were conquered by the Dutch West India Company and colonized by Dutch settlers. From the last quarter of the 17th century, the group consisted of six Dutch islands: Curaçao (settled in 1634), Aruba (settled in 1636), Bonaire (settled in 1636), Sint Eustatius (settled in 1636), Saba (settled in 1640) and Sint Maarten (settled in 1648). In the past, Anguilla (1631–1650), the present-day British Virgin Islands (1612–1672), St. Croix and Tobago had also been Dutch. During the American Revolution Sint Eustatius, along with Curaçao, was a major trade center in the Caribbean, with Sint Eustatius a major source of supplies for the Thirteen Colonies. It had been called "the Golden Rock" because of the number of wealthy merchants and volume of trade there. The British sacked its only town, Oranjestad, in 1781 and the economy of the island never recovered. Unlike many other regions, few immigrants went to the Dutch islands, due to the weak economy. However, with the discovery of oil in Venezuela in the nineteenth century, the Anglo-Dutch Shell Oil Company established refineries in Curaçao, while the U.S. processed Venezuelan crude oil in Aruba. This resulted in booming economies on the two islands, which turned to bust in the 1980s when the oil refineries were closed.[6] The various islands were united as a single country – the Netherlands Antilles – in 1954, under the Dutch crown. The country was dissolved on 10 October 2010.[3] Curaçao and Sint Maarten became distinct constituent countries alongside Aruba which had become a distinct constituent country in 1986; whereas Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba (the "BES Islands") became special municipalities within the Netherlands proper.[7]

From 1815 onwards Curaçao and Dependencies formed a colony of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Slavery was abolished in 1863, and in 1865 a government regulation for Curaçao was enacted that allowed for some very limited autonomy for the colony. Although this regulation was replaced by a constitution (Dutch: Staatsregeling) in 1936, the changes to the government structure remained superficial and Curaçao continued to be ruled as a colony.[8]

The island of Curaçao was hit hard by the abolition of slavery in 1863. Its prosperity (and that of neighboring Aruba) was restored in the early 20th century with the construction of oil refineries to service the newly discovered Venezuelan oil fields.

Colonial rule ended after the conclusion of the Second World War. Queen Wilhelmina had promised in a 1942 speech to offer autonomy to the overseas territories of the Netherlands. During the war, the British and American occupation of the islands – with the consent of the Dutch government – led to increasing demands for autonomy within the population as well.[9]

In May 1948 a new constitution for the territory entered into force, allowing the largest amount of autonomy possible under the Dutch constitution of 1922. Among other things, universal suffrage was introduced. The territory was also renamed "Netherlands Antilles". After the Dutch constitution was revised in 1948, a new interim Constitution of the Netherlands Antilles was enacted in February 1951. Shortly afterwards, on 3 March 1951, the Island Regulation of the Netherlands Antilles (Dutch: Eilandenregeling Nederlandse Antillen or ERNA) was issued by royal decree, giving fairly wide autonomy to the various island territories in the Netherlands Antilles. A consolidated version of this regulation remained in force until the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles in 2010.[10][11]

The new constitution was only deemed an interim arrangement, as negotiations for a Charter for the Kingdom were already under way. On 15 December 1954 the Netherlands Antilles, Suriname and the Netherlands acceded as equal partners to an overarching Kingdom of the Netherlands, established by the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands. With this move, the United Nations deemed decolonization of the territory complete and removed the Netherlands Antilles from the United Nations list of non-self-governing territories.[12]

Aruba seceded from the Netherlands Antilles on 1 January 1986, paving the way for a series of referendums among the remaining islands on the future of the Netherlands Antilles. Whereas the ruling parties campaigned for the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles, the people voted for a restructuring of the Netherlands Antilles. The coalition campaigning for this option became the Party for the Restructured Antilles, which ruled the Netherlands Antilles for much of the time until its dissolution on 10 October 2010.

Dissolution

.svg.png.webp)

Even though the referendums held in the early 1990s resulted in a vote in favour of retaining the Netherlands Antilles, the arrangement continued to be an unhappy one. Between June 2000 and April 2005, each island of the Netherlands Antilles had a new referendum on its future status. The four options that could be voted on were the following:

- closer ties with the Netherlands

- remaining within the Netherlands Antilles

- autonomy as a country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands (status aparte)

- independence

Of the five islands, Sint Maarten and Curaçao voted for status aparte, Saba and Bonaire voted for closer ties with the Netherlands, and Sint Eustatius voted to stay within the Netherlands Antilles.

On 26 November 2005, a Round Table Conference (RTC) was held between the governments of the Netherlands, Aruba, the Netherlands Antilles, and each island in the Netherlands Antilles. The final statement to emerge from the RTC stated that autonomy for Curaçao and Sint Maarten, plus a new status for Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba (BES) would come into effect by 1 July 2007.[13] On 12 October 2006, the Netherlands reached an agreement with Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba: this agreement would make these islands special municipalities.[14]

On 3 November 2006, Curaçao and Sint Maarten were granted autonomy in an agreement,[15] but this agreement was rejected by the then island council of Curaçao on 28 November.[16] The Curaçao government was not sufficiently convinced that the agreement would provide enough autonomy for Curaçao.[17] On 9 July 2007 the new island council of Curaçao approved the agreement previously rejected in November 2006.[18] A subsequent referendum approved the agreement as well.

The acts of parliament integrating the "BES" islands (Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba) into the Netherlands were given royal assent on 17 May 2010. After ratification by the Netherlands (6 July), the Netherlands Antilles (20 August), and Aruba (4 September), the Kingdom act amending the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands with regard to the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles was signed by the three countries in the closing Round Table Conference on 9 September 2010 in The Hague.

Political grouping

| Flag | Name | Capital | Area (km2) | Currency | Official languages | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curaçao | Willemstad | 444 | Netherlands Antillean guilder | Dutch and Papiamento | Capital of the Netherlands Antilles[19] | |

| Bonaire | Kralendijk | 288 | Netherlands Antillean guilder | |||

| Aruba | Oranjestad | 180 | Netherlands Antillean guilder (from 1986 Aruban florin) |

Seceded on 1 January 1986 | ||

| Sint Maarten | Philipsburg | 34 | Netherlands Antillean guilder | Dutch and English | Were parts of the island territory of the Windward Islands until 1 January 1983. | |

| Sint Eustatius | Oranjestad | 21 | Netherlands Antillean guilder | |||

| Saba | The Bottom | 13 | Netherlands Antillean guilder | |||

| Netherlands Antilles | Willemstad | 980 (before 1986) 800 |

Netherlands Antillean guilder |

Constitutional grouping at time of dissolution

The Island Regulation had divided the Netherlands Antilles into four island territories: Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao (ABC), and the islands in the Leeward Islands. In 1983, the island territory of the Leeward was split up to form the new island territories of Sint Maarten, Saba, and Sint Eustatius (SSS). In 1986, Aruba seceded from the Netherlands Antilles, reducing the number of island territories to five. After the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles in 2010, Curaçao and Sint Maarten became autonomous countries within the Kingdom and Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba (BES) became special municipalities of the Netherlands.

Current constitutional grouping

The islands of the former country of the Netherlands Antilles are currently divided in two main groups for political and constitutional purposes:

- those islands that have the status of constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

- those islands that have the status of special municipality of the Netherlands alone, as distinct from the Kingdom in its entirety.

There are also several smaller islands, like Klein Curaçao and Klein Bonaire, that belong to one of the island countries or special municipalities.

Constituent countries

There are three Caribbean islands that are countries (Dutch: landen) within the Kingdom of the Netherlands: Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten. (The Netherlands is the fourth constituent country in the Kingdom of the Netherlands.)

Sint Maarten covers approximately 40% of the island of Saint Martin; the remaining northern part of the island – the Collectivity of Saint Martin – is an overseas territory of France.

Special municipalities

There are three Caribbean islands that are special municipalities of the Netherlands alone: Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba. Collectively, these special municipalities of the Netherlands are also known as the BES islands.

Constitution

The Constitution of the Netherlands Antilles was proclaimed on 29 March 1955 by Order-in-Council for the Kingdom. Together with the Islands Regulation of the Netherlands Antilles it formed the constitutional basis for the Netherlands Antilles. Because the Constitution depended on the Islands Regulation, which gave fairly large autonomy to the different island territories, and the Islands Regulation was older than the Constitution, many scholars describe the Netherlands Antilles as a federal arrangement.[20]

The head of state was the monarch of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, who was represented in the Netherlands Antilles by a governor. The governor and the council of ministers, chaired by a prime minister, formed the government. The Netherlands Antilles had a unicameral legislature called the Parliament of the Netherlands Antilles. Its 22 members were fixed in number for the islands making up the Netherlands Antilles: fourteen for Curaçao, three each for Sint Maarten and Bonaire, and one each for Saba and Sint Eustatius.

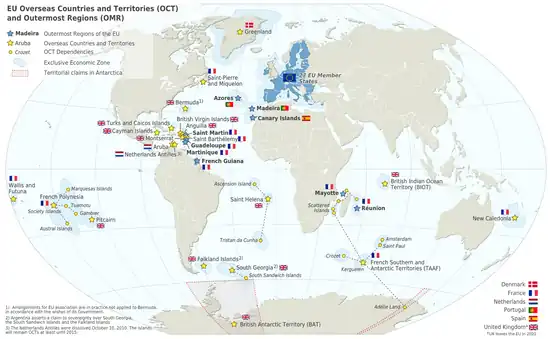

The Netherlands Antilles were not part of the European Union, but instead listed as overseas countries and territories (OCTs). This status was kept for all the islands after dissolution, and will be kept until at least 2015.

Economy

Tourism, petroleum transshipment and oil refinement (on Curaçao), as well as offshore finance were the mainstays of this small economy, which was closely tied to the outside world. The islands enjoyed a high per capita income and a well-developed infrastructure as compared with other countries in the region.[21]

Almost all consumer and capital goods were imported, with Venezuela, the United States, and Mexico being the major suppliers, as well as the Dutch government which supports the islands with substantial development aid. Poor soils and inadequate water supplies hampered the development of agriculture. The Antillean guilder had a fixed exchange rate with the United States dollar of 1.79:1.

Demographics

A large percentage of the Netherlands Antilleans descended from European colonists and African slaves who were brought and traded there from the 17th to 19th centuries. The rest of the population originated from other Caribbean islands as well as Latin America, East Asia and elsewhere in the world. In Curaçao there was a strong Jewish element going back to the 17th century slave trade.

The language Papiamentu was predominant on Curaçao and Bonaire (as well as the neighboring island of Aruba). This creole descended from Portuguese and West African languages with a strong admixture of Dutch, plus subsequent lexical contributions from Spanish and English. An English-based creole dialect, formally known as Netherlands Antilles Creole, was the native dialect of the inhabitants of Sint Eustatius, Saba and Sint Maarten.

After a decades-long debate, English and Papiamentu were made official languages alongside Dutch in early March 2007.[22] Legislation was produced in Dutch, but parliamentary debate was in Papiamentu or English, depending on the island. Due to a massive influx of immigrants from Spanish-speaking territories such as the Dominican Republic in the Windward Islands, and increased tourism from Venezuela in the Leeward Islands, Spanish had also become increasingly used.

The majority of the population were followers of the Christian faith, with a Protestant majority in Sint Eustatius and Sint Maarten, and a Roman Catholic majority in Bonaire, Curaçao and Saba. Curaçao also hosted a sizeable group of followers of the Jewish religion, descendants of a Portuguese group of Sephardic Jews that arrived from Amsterdam and Brazil from 1654. In 1982, there was a population of about 2,000 Muslims, with an Islamic association and a mosque in the capital.[23]

Most Netherlands Antilleans were Dutch citizens and this status permitted and encouraged the young and university-educated to emigrate to the Netherlands. This exodus was considered to be to the islands' detriment, as it created a brain drain. On the other hand, immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Haiti, the Anglophone Caribbean and Colombia had increased their presence on these islands in later years.

Antillean diaspora in the Netherlands

Culture

The origins of the population and location of the islands gave the Netherlands Antilles a mixed culture.

Tourism and overwhelming media presence from the United States increased the regional United States influence. On all the islands, the holiday of Carnival had become an important event after its importation from other Caribbean and Latin American countries in the 1960s. Festivities included "jump-up" parades with beautifully colored costumes, floats, and live bands as well as beauty contests and other competitions. Carnival on the islands also included a middle-of-the-night j'ouvert (juvé) parade that ended at sunrise with the burning of a straw King Momo, cleansing the island of sins and bad luck.

Sports

Netherlands Lesser Antilles competed in the Winter Olympics of 1988, notably finishing 29th in the bobsled, ahead of Jamaica who famously competed but finished 30th.

Baseball is by far the most popular sport. Several players have made it to the Major Leagues, such as Xander Bogaerts, Andrelton Simmons, Hensley Meulens, Randall Simon, Andruw Jones, Kenley Jansen, Jair Jurrjens, Roger Bernadina, Sidney Ponson, Didi Gregorius, Shairon Martis, Wladimir Balentien, and Yurendell DeCaster. Xander Bogaerts won two World Series with the Boston Red Sox, in 2013 and 2018. Andruw Jones played for the Atlanta Braves in the 1996 World Series hitting two home runs in his first game against the New York Yankees.

Three athletes from the former Netherlands Antilles competed in the 2012 Summer Olympics. They, alongside one athlete from South Sudan, competed under the banner of Independent Olympic Athletes.

The Netherlands Antilles, though a non-existing entity since 2010, are allowed to field teams at the Chess Olympiad under this name, because the Curaçao Chess Federation remains officially registered as representing the dissolved country in the FIDE Directory.[24]

Miscellaneous topics

Unlike the metropolitan Netherlands, same-sex marriages were not performed in the Netherlands Antilles, but those performed in other jurisdictions were recognised.

The main prison of the Netherlands Antilles was Koraal Specht, later known as Bon Futuro. It was known for ill treatment of prisoners and bad conditions throughout the years.[25]

The late Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez claimed that the Netherlands was helping the United States to invade Venezuela due to military games in 2006.[26]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Landsverordening officiële talen". decentrale.regelgeving.overheid.nl. 28 March 2007. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ↑ Ratzlaff, Betty. Papiamentu/Ingles Dikshonario (in Papiamento). p. 11.

- 1 2 "Status change means the Dutch Antilles no longer exists". BBC News. 10 October 2010. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ↑ "Visa for the Dutch Caribbean". Netherlands embassy in the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 19 January 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Jennissen, Roel (2014), "On the deviant age-crime curve of Afro-Caribbean populations: The case of Antilleans living in the Netherlands", American Journal of Criminal Justice, 39 (3): 571–594, doi:10.1007/s12103-013-9234-2, S2CID 144184065, archived from the original on 12 January 2024, retrieved 8 December 2020

- ↑ Albert Gastmann, "Suriname and the Dutch in the Caribbean" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 5, p. 189. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ↑ "Antillen opgeheven op 10-10-2010" (in Dutch). NOS . 1 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Oostindie and Klinkers 2001: 12–13

- ↑ Oostindie and Klinkers 2001: 29–32

- ↑ Oostindie and Klinkers 2001: 41–44

- ↑ Overheid.nl – KONINKLIJK BESLUIT van 3 maart 1951, houdende de eilandenregeling Nederlandse Antillen Archived 2 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Oostindie and Klinkers 2001: 47–56

- ↑ "Closing statement of the first Round Table Conference". Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. 26 November 2005. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ↑ Radio Netherlands (12 October 2006). "Caribbean islands become Dutch municipalities". Archived from the original on 13 December 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ↑ "Curaçao and St Maarten to have country status". Government.nl. 3 November 2006. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- ↑ "Curacao rejects final agreement". Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. 29 November 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ↑ "Curaçao verwerpt slotakkoord". Nu.nl. 29 November 2006. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ The Daily Herald St. Maarten (9 July 2007). "Curaçao IC ratifies November 2 accord". Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ↑ "Netherlands Antilles no more". Stabroek News. 9 October 2010. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ Borman 2005:56

- ↑ COUNTRY COMPARISON GDP Archived 4 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ "Antilles allow Papiamentu as official language" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Times Hague/Amsterdam/Rotterdam, 9 March 2007, page 2.

- ↑ Ingvar Svanberg; David Westerlund (6 December 2012). Islam Outside the Arab World. Routledge. p. 447. ISBN 978-1-136-11330-7.

- ↑ "FIDE Directory – Netherlands Antilles". FIDE. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ↑ Rob Gollin (23 February 1998). "Koraalspecht is het ergst, zeggen zelfs Colombiaanse gevangenen". de Volkskrant (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ↑ "Chavez Says Holland Plans to Help US Invade Venezuela". Spiegel.de. 11 April 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

References

- Borman, C. (2005) Het Statuut voor het Koninkrijk, Deventer: Kluwer.

- Oostindie, G. and Klinkers, I. (2001) Het Koninkrijk inde Caraïben: een korte geschiedenis van het Nederlandse dekolonisatiebeleid 1940–2000. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

External links

- Government

- GOV.an – Main governmental site

- Antillenhuis – Cabinet of the Netherlands Antilles' Plenipotentiary Minister in the Netherlands

- Central Bank of the Netherlands Antilles

- General information

- Netherlands Antilles Archived 5 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Netherlands Antilles from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Netherlands Antilles at Curlie

Wikimedia Atlas of Netherlands Antilles

Wikimedia Atlas of Netherlands Antilles

- History

- (in English and Spanish) Method of Securing the Ports and Populations of All the Coasts of the Indies from 1694. The last five pages of the book are about life, economy and culture of the Netherlands Antilles.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)