| Alice in Wonderland syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Todd's syndrome,[1] Lilliputian hallucinations, dysmetropsia |

| |

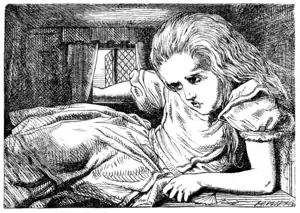

| The perception a person can have due to micropsia, a potential symptom of dysmetropsia. From Lewis Carroll's 1865 novel Alice's Adventures in Wonderland | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology |

| Symptoms |

|

| Complications | Impaired vision |

| Usual onset | Before, during, or after a migraine[3] |

| Duration | Each symptom is separate and will only occur for a 20-to-50-minute period.[4] |

Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AIWS), also known as Todd's syndrome or dysmetropsia, is a neurological disorder that distorts perception. People with this syndrome may experience distortions in their visual perception of objects, such as appearing smaller (micropsia) or larger (macropsia), or appearing to be closer (pelopsia) or farther (teleopsia) than they are. Distortion may also occur for senses other than vision.[5]

The cause of Alice in Wonderland syndrome is currently unknown, but it has often been associated with migraines, head trauma, or viral encephalitis caused by Epstein–Barr virus infection.[6] It is also theorized that AIWS can be caused by abnormal amounts of electrical activity, resulting in abnormal blood flow in the parts of the brain that process visual perception and texture.[7]

Although there are cases of Alice in Wonderland syndrome in both adolescents and adults, it is most commonly seen in children.[2]

Classification

The classification is not universally agreed upon in literature, however, some authors distinguish true Alice in Wonderland syndrome based solely on symptoms related to alterations in a person's body image. In contrast, they utilize the term "Alice in Wonderland-like syndrome" to encompass symptoms associated with changes in perception of vision, time, hearing, touch, or other external perceptions.[2][8]

Signs and symptoms

With over 60 associated symptoms, AIWS affects the sense of vision, sensation, touch, and hearing, as well as the perception of one's body image.[9][10] Migraines, nausea, dizziness, and agitation are also commonly associated symptoms with Alice in Wonderland syndrome.[11] Less frequent symptoms also include: loss of limb control and coordination, memory loss, lingering touch and sound sensations, and emotional instability.[12] Alice in Wonderland syndrome is often associated with distortion of sensory perception, which involves visual, somatosensory, and non-visual symptoms.[13] AIWS is characterized by the individual being able to recognize the distortion in the perception of their own body[14] and is episodic. AIWS episodes vary in length from person to person. Episodes typically last from a few minutes to an hour, and each episode may vary in experience.[15]

Visual distortions

Individuals with AIWS can experience illusions of expansion, reduction, or distortion of their body image, such as microsomatognosia (feeling that their own body or body parts are shrinking), or macrosomatognosia (feeling that their body or body parts are growing taller or larger). These changes in perception are collectively known as metamorphopsias, or Lilliputian hallucinations,[12] which refer to objects appearing either smaller or larger than reality.[16] People with certain neurological diseases may also experience similar visual hallucinations.[17]

Within the category of Lilliputian hallucinations, people may experience either micropsia or macropsia. Micropsia is an abnormal visual condition, usually occurring in the context of visual hallucination, in which the affected person sees objects as being smaller than they are in reality.[18] Macropsia is a condition where the individual sees everything larger than it is.[19] These visual distortions are sometimes classified as "Alice in Wonderland-like syndrome" instead of true Alice in Wonderland syndrome but are often still classified as Alice in Wonderland syndrome by health professionals and researchers since the distinction is not official.[2][8]

It was reported, by Lanska and Lanska (2013), that of all clinical cases, "Some 85% of patients present with perceptual distortions in a single sensory modality, e.g., only visual or only somesthetic. Moreover, the majority experience only a single type of distortion, e.g., only micropsia or only macropsia."[20]

Hallucinations

Zoopsia is an additional hallucination that is sometimes associated with Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Zoopsias involve hallucinations of either swarms of small animals (e.g. ants and mice, etc.), or isolated groups of larger animals (e.g. dogs and elephants, etc.).[21] This experience of zoopsias is a shared symptom of a variety of conditions, such as delirium tremens.[22]

In addition, some people may, in conjunction with a high fever, experience more intense and overt hallucinations, seeing things that are not there, and misinterpreting events and situations.[23]

Depersonalization/derealization

Along with these size, mass, and shape distortions of the body, those with Alice in Wonderland syndrome often experience a feeling of disconnection from one's own body, feelings, thoughts, and environment.[2]

Hearing and time distortions

Individuals experiencing Alice in Wonderland syndrome can also often experience paranoia as a result of disturbances in sound perception. These disturbances can include the amplification of soft sounds or the misinterpretation of common sounds.[24][12] Other auditory changes include distortion in pitch and tone and hearing indistinguishable and strange voices, noises, or music.[11]

A person affected by AIWS may also lose a sense of time, a problem similar to the lack of spatial perspective brought on by visual distortion.[2] This condition is known as tachysensia. For those with tachysensia, time may seem to pass very slowly, similar to an LSD experience, and the lack of time and space perspective can also lead to a distorted sense of velocity. For example, an object could be moving extremely slowly in reality, but to a person experiencing time distortions, it could seem that the object was sprinting uncontrollably along a moving walkway, leading to severe, overwhelming disorientation.[25] Having symptoms of tachysensia is correlated with various underlying conditions, including substance use, migraine, epilepsy, head trauma, and encephalitis. Regardless of an individual's disease diagnosis, tachysensia is often included as a symptom associated with Alice in Wonderland Syndrome since it is classified as a perceptual distortion. Therefore, a person can be described as having Alice in Wonderland syndrome even if that person is experiencing tachysensia due to an underlying condition.[26]

Causes

Because AlWS is not commonly diagnosed and documented, it is difficult to estimate what the main causes are. The cause of over half of the documented cases of Alice in Wonderland syndrome is unknown.[27] Complete and partial forms of the AIWS exist in a range of other disorders, including epilepsy, intoxicants, infectious states, fevers, and brain lesions.[12][28] Furthermore, the syndrome is commonly associated with migraines, as well as excessive screen use in dark spaces and the use of psychoactive drugs. It can also be the initial symptom of the Epstein–Barr virus (see mononucleosis), and a relationship between the syndrome and mononucleosis has been suggested.[6][29][30][11] Within this suggested relationship, Epstein–Barr virus appears to be the most common cause in children, while for adults it is more commonly associated with migraines.[31]

Infectious diseases

A 2021 review found that infectious diseases are the most common cause of Alice in Wonderland syndrome, especially in pediatrics. Some of these infectious agents included Epstein–Barr virus, Varicella Zoster virus, Influenza, Zika,[32] Coxsackievirus, Plasmodium falciparum protozoa, and Mycoplasma pneumonia/Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria.[10] The Association of Alice in Wonderland syndrome is most commonly seen with the Epstein-Barr virus. However, pathogenesis is not well understood beyond these reviews. In some instances, Alice in Wonderland syndrome was reported to be associated with an Influenza A infection.[33][34]

Cerebral hypotheses

Alice in Wonderland syndrome can be caused by abnormal amounts of electrical activity resulting in abnormal blood flow in the parts of the brain that process visual perception and texture.[7] Nuclear medical techniques using technetium, performed on individuals during episodes of Alice in Wonderland syndrome, have demonstrated that Alice in Wonderland Syndrome is associated with reduced cerebral perfusion in various cortical regions (frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital), both in combination and in isolation. One hypothesis is that any condition resulting in a decrease in perfusion of the visual pathways or visual control centers of the brain may be responsible for the syndrome. For example, one study used single photon emission computed tomography to demonstrate reduced cerebral perfusion in the temporal lobe in people with Alice in Wonderland syndrome.[35]

Other theories suggest the syndrome is a result of non-specific cortical dysfunction (e.g. from encephalitis, epilepsy, decreased cerebral blood flow), or reduced blood flow to other areas of the brain.[12][11] Other theories suggest that distorted body image perceptions stem from within the parietal lobe. This has been demonstrated by the production of body image disturbances through electrical stimulation of the posterior parietal cortex. Other researchers suggest that metamorphopsias, or visual distortions, may be a result of reduced perfusion of the non-dominant posterior parietal lobe during migraine episodes.[12]

Throughout all the neuroimaging studies, several cortical regions (including the temporoparietal junction within the parietal lobe, and the visual pathway, specifically the occipital lobe) are associated with the development of Alice in Wonderland syndrome symptoms.[1]

Migraines

The role of migraines in Alice in Wonderland syndrome is still not understood, but both vascular and electrical theories have been suggested. For example, visual distortions may be a result of transient, localized ischemia in areas of the visual pathway during migraine attacks. In addition, a spreading wave of depolarization of cells (particularly glial cells) in the cerebral cortex during migraine attacks can eventually activate the trigeminal nerve's regulation of the vascular system. The intense cranial pain during migraines is due to the connection of the trigeminal nerve with the thalamus and thalamic projections onto the sensory cortex. Alice in Wonderland syndrome symptoms can precede, accompany, or replace the typical migraine symptoms.[12] Typical migraines (aura, visual derangements, hemicrania headache, nausea, and vomiting) are both a cause and an associated symptom of Alice in Wonderland Syndrome.[14] Alice in Wonderland Syndrome is associated with macrosomatognosia which can mostly be experienced during migraine auras.[36]

Genetic and environmental influence

While there currently is no identified genetic locus/loci associated with Alice in Wonderland syndrome, observations suggest that a genetic component may exist but the evidence so far is inconclusive. There is also an established genetic component for migraines which may be considered to be a possible cause and influence for hereditary Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Though most frequently described in children and adolescents, observational studies have found that many parents of children experiencing Alice in Wonderland syndrome have also experienced similar symptoms themselves, though often unrecognized.[27] Family history may then be a potential risk factor for Alice in Wonderland syndrome.

One example of environmental influences on the incidence of Alice in Wonderland syndrome includes the drug use and toxicity of topiramate.[37] Other reports of tyramine usage and the association with Alice in Wonderland syndrome has been reported but current evidence is inconclusive. Further research is required to establish the genetic and environmental influences on Alice in Wonderland syndrome.[11]

The neuronal effect of cortical spreading depression (CSD) on TPO-C may demonstrate the link between migraines and Alice in Wonderland Syndrome. As children experience Alice in Wonderland Syndrome more than adults, it is hypothesized that structural differences in the brain between children and adults may play a role in the development of this syndrome.[31][38]

Diagnosis

Alice in Wonderland syndrome is not part of any major classifications like the ICD-10[39] and the DSM-5.[40] Since there are no established diagnostic criteria for Alice in Wonderland syndrome, and because Alice in Wonderland syndrome is a disturbance of perception rather than a specific physiological condition, there is likely to be a large degree of variability in the diagnostic process and thus it can be poorly diagnosed.[31] Often, the diagnosis can be presumed when other causes have been ruled out. Additionally, Alice in Wonderland syndrome can be presumed if the patient presents symptoms along with migraines and complains of onset during the day (although it can also occur at night). Ideally, a definite diagnosis requires a thorough physical examination, proper history taking of episodes and occurrences, and a concrete understanding of the signs and symptoms of Alice in Wonderland syndrome for differential diagnosis. A person experiencing Alice in Wonderland syndrome may be reluctant to describe their symptoms out of fear of being labeled with a psychiatric disorder, which can contribute to the difficulty in diagnosing Alice in Wonderland syndrome. In addition, younger individuals may struggle to describe their unusual symptoms, and thus, one recommended approach is to encourage children to draw their visual illusions during episodes.[12] Cases that are suspected should warrant tests and exams such as blood tests, ECG, brain MRI, and other antibody tests for viral antibody detection.[14] Differential diagnosis requires three levels of conceptualization. Symptoms need to be distinguished from other disorders that involve hallucinations and illusions. It is usually easy to rule out psychosis as those with Alice in Wonderland syndrome are typically aware that their hallucinations and distorted perceptions are not 'real'.[11] Once these symptoms are distinguished and identified, the most likely cause needs to be established. Finally, the diagnosed condition needs to be evaluated to see if the condition is responsible for the symptoms that the individual is presenting.[13] Given the wide variety of metamorphopsias and other distortions, it is not uncommon for Alice in Wonderland syndrome to be misdiagnosed or confused with other etiologies.

Anatomical relation

An area of the brain that is important to the development of Alice in Wonderland syndrome is the temporal-parietal-occipital carrefour (TPO-C),[31][41] where TPO-C region is the meeting point of temporooccipital, parietooccipital, and temporoparietal junctions in the brain. The TPO-C region is also crucial as it is the location where somatosensory and visual information are interpreted by the brain to generate any internal or external manifestations. Thus, modifications to these regions of the brain may trigger the cause of Alice in Wonderland Syndrome and body schema disorders simultaneously .[31]

Depending on which portion of the brain is damaged, the symptoms of Alice in Wonderland syndrome may differ. For example, it has been reported that injury to the anterior portion of the brain is more likely to be correlated to more complex and a wider range of symptoms, whereas damage to the occipital region has mainly been associated with only simple visual disturbances.[31]

Prognosis

The symptoms of Alice in Wonderland syndrome themselves are not inherently harmful and are often not frightening to the experiencer. Since there is no established treatment for Alice in Wonderland syndrome, prognosis varies between patients and is based on whether an underlying cause has been identified.[27]

If Alice in Wonderland Syndrome is caused by underlying conditions, symptoms typically occur during the underlying disease and can last from few days to months.[11] In most cases, symptoms may disappear either spontaneously, with the treatment of underlying causes, or after reassurances that symptoms are momentary and harmless.[13] In some cases it is experienced no more than a few episodes of symptoms, in other cases, symptoms may repeat several episodes before resolve. In rare cases, symptoms continue to manifest years after the initial experience, sometimes with the development of new visual disorders or migraines.[27]

Treatment

At present (2023), Alice in Wonderland Syndrome has no standardized treatment plan.[42] Since symptoms of Alice in Wonderland syndrome often disappear, either spontaneously on their own, or with the treatment of the underlying disease, most clinical and non-clinical Alice in Wonderland Syndrome cases are considered to be benign. In cases of Alice in Wonderland syndrome caused by underlying chronic disease, however, symptoms tend to reappear during the active phase of the underlying cause (e.g., migraine, epilepsy). If treatment of Alice in Wonderland Syndrome is determined necessary and useful, it should be focused on treating the suspected underlying disease. Treatment of these underlying conditions mostly involves prescription medications such as antiepileptics, migraine prophylaxis, antivirals, or antibiotics. Antipsychotics are rarely used in treating Alice in Wonderland Syndrome symptoms due to their minimal effectiveness.[13]

Migraine prophylaxis

Treatment methods revolving around migraine prophylaxis include medications and following a low-tyramine diet. Drugs that may be used to prevent migraines include anticonvulsants, antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, and beta blockers. Other treatments that have been explored for migraines include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). However, further research is needed to establish the effectiveness of this treatment regime.[11]

Epidemiology

The lack of established diagnostic criteria or large-scale epidemiological studies, low awareness of the syndrome, and the unstandardized diagnosis criteria and definition for Alice in Wonderland syndrome mean that the exact prevalence of the syndrome is currently unknown. One study on 3,224 adolescents in Japan demonstrated the occurrence of macropsia and micropsia to be 6.5% in boys and 7.3% in girls, suggesting that the symptoms of Alice in Wonderland syndrome may not be particularly rare.[43] This also seems to suggest a difference in the male-to-female ratio of people with Alice in Wonderland syndrome. However, according to other studies, it appears that the male/female ratio is dependent on the age range being observed. Studies showed that younger males (age range of 5 to 14 years) were 2.69 times more likely to experience Alice in Wonderland syndrome than girls of the same age, while there were no significant differences between students of 13 to 15 years of age. Conversely, female students (16- to 18-year-olds) showed a significantly greater prevalence.[31]

Alice in Wonderland syndrome is more frequently seen in children and young adults.[38] The average age of the start of Alice in Wonderland syndrome is six years old, but it is typical for some people to experience the syndrome from childhood up to their late twenties.[11] Because many parents who have Alice in Wonderland syndrome report their children having it as well, the condition is thought possibly to be hereditary.[14] Some parents report not realizing they have experienced Alice in Wonderland syndrome symptoms until after their children have been diagnosed, further indicating that many cases of Alice in Wonderland syndrome likely go unrecognized and under-reported.[27]

Research is still being expanded upon and developed on this syndrome in a multitude of different regions and specialties.[44] Future studies are encouraged to include global collaborative efforts that may help improve understanding of Alice in Wonderland syndrome and its epidemiology.

History

The syndrome is sometimes called Todd's syndrome, about a description of the condition in 1955 by Dr. John Todd (1914–1987), a British consultant psychiatrist at High Royds Hospital at Menston in West Yorkshire.[45][46] Dr. Todd discovered that several of his patients experienced severe headaches causing them to see and perceive objects as greatly out of proportion. In addition, they had altered sense of time and touch, as well as distorted perceptions of their own body. Despite having migraine headaches, none of these patients had brain tumors, damaged eyesight, or mental illness that could have accounted for these and similar symptoms. They were all able to think lucidly and could distinguish hallucinations from reality, however, their perceptions were distorted.[47]

Dr. Todd speculated that author Lewis Carroll had used his own migraine experiences as a source of inspiration for his famous 1865 novel Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Carroll's diary reveals that, in 1856, he consulted William Bowman, an ophthalmologist, about the visual manifestations of the migraines he regularly experienced.[48] In Carroll's diaries, he often wrote of a "bilious headache" that came coupled with severe nausea and vomiting. In 1885, he wrote that he had "experienced, for the second time, that odd optical affection of seeing moving fortifications, followed by a headache".[49] Carroll wrote two books about Alice, the heroine after which the syndrome is named. In the story, Alice experiences several strange feelings that overlap with the characteristics of the syndrome, such as slowing time perception. In chapter two of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Alice's body shrinks after drinking from a bottle labeled "DRINK ME", after which she consumed a cake that made her so large that she almost touched the ceiling.[50] These features of the story describes the macropsia and micropsia that are so characteristic to this disease.

These symptoms have been reported before in scientific literature, including World War I and II soldiers with occipital lesions, so Todd understood that he was not the first person to discover this phenomenon. Additionally, as early as 1933, other researchers such as Coleman and Lippman had compared these symptoms to the story of Alice in Wonderland. Caro Lippman was the first to hypothesize that the bodily changes that Alice encounters mimicked those of Lewis Carroll's migraine symptoms. Others suggest that Carroll may have familiarized himself with these distorted perceptions through his knowledge of hallucinogenic mushrooms.[13] It has been suggested that Carroll would have been aware of mycologist Mordecai Cubitt Cooke's description of the intoxicating effects of the fungus Amanita muscaria (commonly known as the fly agaric or fly amanita), in his books The Seven Sisters of Sleep and A Plain and Easy Account of British Fungi.[51][52]

Notable cases

- In 2018 it was suggested that the Italian artist and writer Giorgio de Chirico may have suffered from the syndrome.[53]

Society and culture

Gulliver's Travels

Alice in Wonderland syndrome's symptom of micropsia has also been related to Jonathan Swift's novel Gulliver's Travels. It has been referred to as "Lilliput sight" and "Lilliputian hallucination", a term coined by British physician Raoul Leroy in 1909.[54]

Alice in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland syndrome was named after Lewis Carroll's 19th-century novel Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. In the story, Alice, the titular character, experiences numerous situations similar to those of micropsia and macropsia. The thorough descriptions of metamorphosis clearly described in the novel were the first of their kind to depict the bodily distortions associated with the condition. There is some speculation that Carroll may have written the story using his own direct experience with episodes of micropsia resulting from the numerous migraines he was known to experience.[48] It has also been suggested that Carroll may have had temporal lobe epilepsy.[55]

House

The condition is diagnosed in the season 8 episode "Risky Business".

Doctors

In April 2020, a case of Alice in Wonderland syndrome was covered in an episode of the BBC daytime soap opera Doctors, when patient Hazel Gilmore (Alex Jarrett) experienced it.[56]

See also

References

- ↑ Longmore M, Wilkinson I, Turmezei T, Cheung CK (2007). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. Oxford. p. 686. ISBN 978-0-19-856837-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Lanska, Douglas J.; Lanska, John R. (2018), Bogousslavsky, J. (ed.), "The Alice-in-Wonderland Syndrome", Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience, S. Karger AG, 42: 142–150, doi:10.1159/000475722, ISBN 978-3-318-06088-1, PMID 29151098, retrieved 2021-07-27

- ↑ Goad, Kimberly. "Signs of a Migraine That Aren't Headache". WebMD.

- ↑ "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome | Symptoms & Treatment". Share.upmc.com. 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ↑ Weissenstein, Anne; Luchter, Elisabeth; Bittmann, M.A. Stefan (2014). "Alice in Wonderland syndrome: A rare neurological manifestation with microscopy in a 6-year-old child". Journal of Pediatric Neurosciences. 9 (3): 303–304. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.147612. ISSN 1817-1745. PMC 4302569. PMID 25624952.

- 1 2 Cinbis M, Aysun S (1992). "Alice in Wonderland syndrome as an initial manifestation of Epstein-Barr virus infection". Br J Ophthalmol. 76 (5): 314. doi:10.1136/bjo.76.5.316. PMC 504267. PMID 1390519.

- 1 2 Feldman, Caroline (2008). "A Not So Pleasant Fairy Tale: Investigating Alice in Wonderland Syndrome". Serendip. Serendip Studio, Bryn Mawr College. Archived from the original on November 9, 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- 1 2 Podoll, K.; Ebel, H.; Robinson, D.; Nicola, U. (2002). "[Obligatory and facultative symptoms of the Alice in wonderland syndrome]". Minerva Medica. 93 (4): 287–293. ISSN 0026-4806. PMID 12207198.

- ↑ Stapinski H (2014). "I Had Alice in Wonderland Syndrome". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- 1 2 Perez-Garcia, Luis; Pacheco, Oriana; Delgado-Noguera, Lourdes; Motezuma, Jean Pilade M.; Sordillo, Emilia M.; Paniz Mondolfi, Alberto E (2021). "Infectious causes of Alice in Wonderland syndrome". Journal of NeuroVirology. 27 (4): 550–556. doi:10.1007/s13365-021-00988-8. ISSN 1355-0284. PMID 34101086. S2CID 235369619.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 O'Toole P, Modestino EJ (2017). "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: A real-life version of Lewis Carroll's novel". Brain & Development. 39 (6): 470–474. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2017.01.004. PMID 28189272. S2CID 3624078.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Farooq O, Fine EJ (2017). "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: A Historical and Medical Review". Pediatric Neurology. 77: 5–11. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.08.008. PMID 29074056.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Blom, Jan Dirk (2016). "Alice in Wonderland syndrome". Neurology: Clinical Practice. 6 (3): 259–270. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000251. ISSN 2163-0402. PMC 4909520. PMID 27347442.

- 1 2 3 4 Weissenstein, Anne; Luchter, Elisabeth; Bittmann, M.A. Stefan (2014). "Alice in Wonderland syndrome: A rare neurological manifestation with microscopy in a 6-year-old child". Journal of Pediatric Neurosciences. 9 (3): 303–304. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.147612. ISSN 1817-1745. PMC 4302569. PMID 25624952.

- ↑ Palacios-Sánchez, Leonardo; Botero-Meneses, Juan Sebastián; Mora-Muñoz, Laura; Guerrero-Naranjo, Alejandro; Moreno-Matson, María Carolina; Pachón, Natalia; Charry-Sánchez, Jesús David (2018). "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS). A reflection". Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology. 46 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1097/CJ9.0000000000000026. ISSN 2256-2087. S2CID 194848505.

- ↑ Craighead WE, Nemeroff CB, eds. (2004). "Hallucinations". The Concise Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology and Behavioral Science. Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-22036-7.

- ↑ "Alice in Wonderland syndrome". Mosby's Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing & Health Professions. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009. ISBN 978-0-323-22205-1.

- ↑ "Micropsia". Mosby's Emergency Dictionary. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences. 1998.

- ↑ "Macropsia". Collins English Dictionary. London: Collins. 2000. ISBN 978-0-00-752274-3. Archived from the original on 2018-01-07.

- ↑ Naarden, Tirza; ter Meulen, Bastiaan C.; van der Weele, Sarah I.; Blom, Jan Dirk (November 10, 2019). "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome as a Presenting Manifestation of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease". Frontiers in Neurology. 10: 473. doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00473. PMC 6521793. PMID 31143156.

- ↑ Ffytche DH (2007). "Visual hallucinatory syndromes: past, present, and future". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 9 (2): 173–89. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.2/dffytche. PMC 3181850. PMID 17726916.

- ↑ Platz WE, Oberlaender FA, Seidel ML (1995). "The phenomenology of perceptual hallucinations in alcohol-induced delirium tremens". Psychopathology. 28 (5): 247–255. doi:10.1159/000284935. PMID 8559948.

- ↑ "What Is Alice in Wonderland Syndrome?". WebMD. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- ↑ Hemsley R (2017). "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome". aiws.info. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- ↑ "The Alice In Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS) - frontida". SUPPORTS A HEALTHY LIFE. 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- ↑ Blom, Jan Dirk; Nanuashvili, Nutsa; Waters, Flavie (2021). "Time Distortions: A Systematic Review of Cases Characteristic of Alice in Wonderland Syndrome". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12: 668633. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.668633. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 8138562. PMID 34025485.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Liu, Alessandra M.; Liu, Jonathan G.; Liu, Geraldine W.; Liu, Grant T. (2014). ""Alice in Wonderland" Syndrome: Presenting and Follow-Up Characteristics". Pediatric Neurology. 51 (3): 317–320. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.04.007. ISSN 0887-8994. PMID 25160537.

- ↑ Brooks, Joseph Bruno Bidin; Prosdocimi, Fabio César; Rosa, Pedro Banho da; Fragoso, Yara Dadalti (2019). "Alice in Wonderland syndrome: "Who in the world am I?"". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 77 (9): 672–674. doi:10.1590/0004-282x20190094. ISSN 1678-4227. PMID 31553398. S2CID 202760880.

- ↑ Eshel, Lahat (1991). ""Alice in Wonderland" syndrome: a manifestation of infectious mononucleosis in children". Behavioural Neurology. 4 (3): 163–166. doi:10.3233/BEN-1991-4304. PMID 24487499. S2CID 41470230.

- ↑ "Alice in Wonderland syndrome". Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company. 2009. ISBN 978-0-8036-2325-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mastria G; Mancini V; Viganò A; Di Piero V (2016). "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: A Clinical and Pathophysiological Review". BioMed Research International. 2016: 8243145. doi:10.1155/2016/8243145. PMC 5223006. PMID 28116304.

- ↑ Paniz-Mondolfi, Alberto E.; Giraldo, José; Rodríguez-Morales, Alfonso J.; Pacheco, Oriana; Lombó-Lucero, Germán Y.; Plaza, Juan D.; Adami-Teppa, Fabio J.; Carrillo, Alejandra; Hernandez-Pereira, Carlos E.; Blohm, Gabriela M. (2018). "Alice in Wonderland syndrome: a novel neurological presentation of Zika virus infection". Journal of NeuroVirology. 24 (5): 660–663. doi:10.1007/s13365-018-0645-1. ISSN 1355-0284. PMID 30105501. S2CID 51971475.

- ↑ Kuo, Shin-Chang; Yeh, Yi-Wei; Chen, Chun-Yen; Weng, Ju-Ping; Tzeng, Nian-Sheng (2012). "Possible Association Between Alice In Wonderland Syndrome And Influenza A Infection". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 24 (3): E7–E8. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11080177. ISSN 0895-0172. PMID 23037657.

- ↑ Kubota, Kazuo; Shikano, Hiroaki; Fujii, Hidehiko; Nakashima, Yoshiki; Ohnishi, Hidenori (2020). "Alice in Wonderland syndrome associated with influenza virus infection". Pediatrics International. 62 (12): 1391–1393. doi:10.1111/ped.14341. ISSN 1328-8067. PMID 33145932. S2CID 226250633.

- ↑ Kuo YT, Chiu NC, Shen EY, Ho CS, Wu MC (1998). "Cerebral perfusion in children with Alice in Wonderland syndrome". Pediatric Neurology. 19 (2): 105–8. doi:10.1016/s0887-8994(98)00037-x. PMID 9744628.

- ↑ Dieguez, Sebastian; Lopez, Christophe (2017). "The bodily self: Insights from clinical and experimental research". Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 60 (3): 198–207. doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2016.04.007. ISSN 1877-0657. PMID 27318928. S2CID 26966204.

- ↑ Jürgens, T. P.; Ihle, K.; Stork, J.-H.; May, A. (2011). ""Alice in Wonderland syndrome" associated with topiramate for migraine prevention". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 82 (2): 228–229. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2009.187245. ISSN 0022-3050. PMID 20571045. S2CID 29359144.

- 1 2 Valença, Marcelo Hugo; de Oliveira, Daniella; André, de L. Martins (2015). "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, Burning Mouth Syndrome, Cold Stimulus Headache, and HaNDL: Narrative Review". The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 55 (9): 1233–1248. doi:10.1111/head.12688. PMID 26422755. S2CID 23693209.

- ↑ Whitfield, William (1993). "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines by World Health Organization". Book Reviews. Journal of the Royal Society of Health. 113 (2): 103. doi:10.1177/146642409311300216. ISSN 0264-0325. S2CID 221056866.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. 2011.

- ↑ Hadjikhani, Nouchine; Vincent, Maurice (2021). "Visual Perception in Migraine: A Narrative Review". Vision. 5 (2): 20. doi:10.3390/vision5020020. ISSN 2411-5150. PMC 8167726. PMID 33924855.

- ↑ O'Toole, Patrick; Modestino, Edward (2017). "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: A real-life version of Lewis Carroll's novel". Brain and Development. 39 (6): 470–474. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2017.01.004. ISSN 0387-7604. PMID 28189272. S2CID 3624078.

- ↑ Abe, Kazuhiro; Oda, Noboru; Araki, Ryuji; Igata, Masayuki (1989). "Macropsia, micropsia, and episodic illusions in Japanese adolescents". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 28 (4): 493–6. doi:10.1097/00004583-198907000-00004. PMID 2788641.

- ↑ Hossain, Mahbub (2020). "Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AIWS): a research overview". AIMS Neuroscience. 7 (4): 389–400. doi:10.3934/Neuroscience.2020024. ISSN 2373-7972. PMC 7701374. PMID 33263077.

- ↑ Todd, J (1955). "The syndrome of Alice in Wonderland". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 73 (9): 701–4. PMC 1826192. PMID 13304769.

- ↑ Lanska, John; Lanska, Douglas (2013). "Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: somesthetic vs visual perceptual disturbance". Neurology. 80 (13): 1262–4. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828970ae. PMID 23446681. S2CID 38722468.

- ↑ Cau C (1999). "La sindrome di Alice nel paese delle meraviglie" [The Alice in Wonderland syndrome]. Minerva Medica (in Italian). 90 (10): 397–401. PMID 10767914.

- 1 2 Martin R. "Through the Looking Glass, Another Look at Migraine" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ Green, Roger; Cohen, Morton (1964). "Lewis Carroll Correspondence". Notes and Queries. 11 (7): 271–e–271. doi:10.1093/nq/11-7-271e. ISSN 1471-6941.

- ↑ Carroll, Lewis (2015-12-31). Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. doi:10.1515/9781400874262. ISBN 9781400874262.

- ↑ Letcher, Andy (2006). Shroom: A Cultural History. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 123, 127. ISBN 978-0-571-22770-9.

- ↑ Hanson, Dirk (2014). ""Eye on fiction: Heavenly and hellish - writers on hallucinogens"". The Psychologist, the Monthly Publication of the British Psychological Society. 27: 680.

- ↑ Chirchiglia, D; Chirchiglia, P; Marotta, R (2018). "De Chirico and Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: When Neurology Creates Art". Frontiers in Neurology. 9 (553). doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.00553. PMC 6099085. PMID 30150967.

- ↑ Chand PK, Murthy P (2007). "Understanding a Strange Phenomenon: Lilliputian Hallucinations". German Journal of Psychiatry. Archived from the original on 2009-01-23. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ↑ Angier N (1993). "In the Temporal Lobes, Seizures and Creativity". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2017-09-13. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- ↑ Writer: Lisa McMullin; Director: Daniel Wilson; Producer: Peter Leslie Wild (7 April 2020). "Al Through the Looking Glass". Doctors. BBC. BBC One.