Edward Howland Robinson Green | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Green in 1923 | |

| Born | August 22, 1868 London, England |

| Died | June 8, 1936 (aged 67) Lake Placid, New York |

| Education | Fordham College |

| Occupation(s) | Businessman, politician |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Mabel E. Harlow |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Harriet Sylvia Ann Howland Green Wilks (sister) |

| Signature | |

.png.webp) | |

Edward Howland Robinson "Ned" Green (August 22, 1868 – June 8, 1936), also known as Colonel Green, was an American businessman, the only son of financier Hetty Green (the "Witch of Wall Street"). In the late 19th century, he became a political ally in the Republican Party of William Madison McDonald, a prominent African-American politician.

After his mother's death in 1916 and his inheritance of half her fortune, Green built a mansion in Round Hill, Massachusetts. He was noted for his stamp and coin collections.

Youth

Edward Green was born at the Langham Hotel, London, on August 22, 1868, the first of two children of Hetty and Edward Henry Green.[1] His sister Harriet Sylvia Ann Howland Green Wilks, called Sylvia, was born in 1871. Their mother amassed a fortune through her business dealings and was known as a miser.[2]

Ned broke his leg as a child, and Hetty first tried to have him admitted to a free clinic for the poor.[2] Charles Slack, her biographer, said that she was recognized; she was unwilling to pay for the medical services and treated him herself. The boy's leg did not heal properly and had to be amputated due to gangrene. Ned used a cork prosthesis.[3][4] He grew to 6'4" (1.93 m) and 300 lb. (136 kg) as an adult.[3]

Green attended private schools and graduated from Fordham College in 1888.[5] He later studied real estate law.[6][7]

Career

In 1893, Green was assigned by his mother to manage the Texas Midland Railroad,[5][8][9] which she had acquired by foreclosure.[6] He went to Terrell, Texas, and turned the ailing enterprise into "a model railroad boasting the first electrically-lighted coaches in the State."[6][9] This was only one of many business ventures in which Green succeeded.[6]

Green was also active in state politics. In 1896, he began a long-lasting political partnership with William Madison McDonald, an African-American leader of the Black and Tan faction of the Republican Party from Fort Worth.[5] In 1910, though a Republican, Green was made "a Colonel on the staff of a Democratic Governor of Texas".[5][6]

Social life

In contrast to his mother, Green spent lavishly and partied. He surrounded himself with attractive young women,[5] who were well paid for their services.[6]

In 1911, Green was interviewed and sketched by Marguerite Martyn of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. She said that he was a "fine, stalwart, upstanding millionaire, middle-aged . . . wholesome and hearty, with a most ingratiating, breezy Western way with him." He told her that he received "thousands of letters" from women offering to marry him and that "a secretary had been appointed to take charge of this class of mail." Green told Martyn: "Why, it isn't my money they want to marry me for. It's alimony."[10]

As Hetty strongly opposed his marrying, he waited until after her death in 1916 to wed his longtime companion, Mabel E. Harlow, a former prostitute.[5][6]

Inheritance

He and his sister Sylvia each inherited half of their mother's fortune, estimated at between $100 million to $200 million (equivalent to $2.7 billion to $5.4 billion in 2024). In addition to the various other homes he already owned, after his mother's death, Green built a mansion in Massachusetts, Round Hill,[6][11] and another on Star Island, Florida.[3] The Round Hill mansion was designed by the Anglo-American architect Alfred C. Bossom and completed in 1921 at a cost of $1.5 million.[11]

Interests

Green is known to philatelists for forming one of the great collections of postage stamps of the early 20th century, exceeded in size and value only by that of King George V. In 1918, he purchased the sheet of Inverted Jenny stamps from the dealer Eugene Klein for $20,000. On Klein's advice, he broke the sheet up into blocks. He put one stamp in a locket he gave to his wife.

To numismatists, Green is known for his extensive coin collection.[12] Most notably, he was one of the original owners of all five of the 1913 Liberty Head nickels known to exist.[13]

He brought one of the first automobiles into Texas, "a two-cylinder St. Louis Gas Car surrey, designed by George Norris [sic - the correct name is Dorris]",[14] and is reputed to have been involved in the first car accident in the state, when the car was forced off the road into a ditch by a farm wagon in October 1899 in Forney, Texas.[15][16] He eventually owned a large fleet of cars, many modified with special transmissions on account of his prosthetic leg.[17]

In 1924, Green rescued the last American wooden whaling vessel of the 19th century, the bark Charles W. Morgan, and exhibited her, embedded in sand, at Round Hill. Green was the grandson of Edward Mott Robinson, one of the ship's earlier owners. The Marine Historical Association bought her in 1941, when she became a showpiece of Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, Connecticut.[18]

In 1927, he opened an airfield on his property, and kept the field well-maintained according to people who flew there. Following his son's kidnapping, Charles Lindbergh landed on the property in order to investigate a lead about his whereabouts.[19]

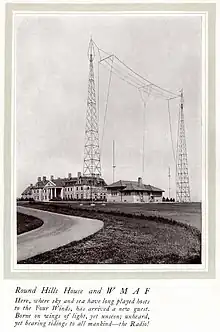

Radio research and WMAF

Colonel Green had an early fascination with radio technology, dating back to the 1890s. In June 1922, the Round Hills Radio Corporation was incorporated under a commercial charter, with Colonel Green the company president. Under the initial charter, the company's function, in addition to engaging in radio broadcasting, was to sell radio, telephone and similar equipment. However, because the company did not actually engage in commercial activities, in August of the next year it was rechartered under the state's charitable and educational statutes, with its mission now described as "for radio experimentation, improving the uses of wireless and scientific experimentation in new devices to further the use of radio, and to broadcast, free of charge, concerts, weather reports, etc."[20]

To support the radio operations, a building containing a broadcast studio plus laboratory rooms was constructed adjacent to the estate's main building. MIT's President, Samuel W. Stratton and the Department of Electrical Engineering's new Communications Division were invited to experiment with the new technology, and the department was initially financed by Green.

In September 1922, the Round Hills Radio Corporation received licenses for a broadcasting station, WMAF, in addition to one for experimental work, with the call sign 1XV. The broadcasting station, which was operated only during the summer months of 1923–1928, adopted the slogan The Voice from Way Down East. For the summer of 1923, Green arranged for the American Telephone & Telegraph Company (AT&T) to install a telephone line connection to rebroadcast the programs originating from WEAF (now WFAN) in New York City, which was the first permanent radio network link.[21]

Professor Edward L. Bowles set out to determine the signal strength and radiation patterns of different antenna arrays in 1926. Round Hill's radio station (which included an early radio telescope, built atop a water tower designed to look like the foundation of a lighthouse) followed Donald B. MacMillan's and Admiral Richard E. Byrd's polar expeditions, tracked the Graf Zeppelin dirigible during its maiden transatlantic flight, and was the sole communication link for areas devastated by the Vermont floods in 1927.

Van de Graaff

In 1933, Round Hill was the site of Robert J. Van de Graaff's electrical experiments. Van de Graaff had been brought to MIT from Princeton in 1931 to develop a high voltage research facility. He built a 40-foot (12 m) tall Van de Graaff generator in an abandoned airship hangar on Round Hill. The purpose was to provide the energy to accelerate subatomic particles to bombard atomic nuclei. The machine became operational in December 1933. It was capable of operating at 5,000,000 volts. After it became obsolete, the generator was donated in 1956 to the Museum of Science, Boston, and circa 2019 the generator continues to function as a major exhibit.[22]

Death

He died of heart disease at Lake Placid, New York, in 1936.[5] In accordance with Green's last request, his widow had his amputated leg exhumed and reunited with the rest of his body.[5]

His widow and his sister fought over his estate, estimated at the time as $44,384,500[6] or "more than $40 million".[5] Green had persuaded Mabel to sign a prenuptial agreement, which limited her to a $1,500 monthly stipend, but she challenged it in court. She eventually settled for $500,000.[17]

Four states, Texas, Massachusetts, Florida and New York, fought over who would collect $6 million in inheritance taxes. The United States Supreme Court awarded the money to Massachusetts.[5][23]

References

- ↑ Hall, Henry (1895). America's Successful Men of Affairs. An Encyclopedia of Contemporaneous Biography. New York: New York Tribune. pp. 277–279.

- 1 2 Slack, Charles, Hetty: The Genius And Madness Of America's First Female Tycoon, New York: Ecco (2004) ISBN 0-06-054256-X.

- 1 2 3 Zimmerman, Paul (1982). "The Star of Star Island". Sports Illustrated. No. December 13, 1982.

- ↑ Wicklund, Doug (June 12, 2017). "A Sea-Going Arsenal: Guns of the Yacht United States".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Debbie Mauldin Cottrell. "Green, Edward Howland Robinson (1868–1936)". Handbook of Texas. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Green Grist". Time magazine. May 3, 1937. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ↑ Hall, Henry (1895). America's Successful Men of Affairs. An Encyclopedia of Contemporaneous Biography. New York: New York Tribune. pp. 277–279.

He then studied law, paying especial attention to the statutes pertaining to real estate and railroads.

- ↑ "McDonald, William Madison (1866-1950)". BlackPast.org. October 13, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- 1 2 S. G. Reed. "Texas Midland Railroad". Handbook of Texas. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Hetty Green's Son Tells Marguerite Martyn Why He has Never Married; What His Ideal Wife Is Like: The Barrels of Proposals He Gets: His Own Shattered Romance". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. May 7, 1911. Retrieved December 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Round Hill Lab Site, Massachusetts". Center for Land Use Interpretation.

- ↑ Heritage Numismatic Auctions Presents the Gold Rush Collection Catalog #360. Dallas, Texas: Heritage Capital Corporation. 2004. p. 19. ISBN 1-932899-44-8.

- ↑ Montgomery, Paul; Borckardt, Mark; Knight, Ray (2005). Million Dollar Nickels. Irvine, California: Zyrus Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-9742371-8-3.

- ↑ Clay Coppedge (December 24, 2009). "Ned Green". Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ↑ "History". Terrell Chamber of Commerce Convention & Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ↑ "Automobile Trip, 1899". Forney Historic Preservation League. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- 1 2 "Ned Liked to Spend Money". Life. No. February 19, 1951. 1951. p. 46.

- ↑ National Register of Historic Places, Inventory and Nomination

- ↑ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Southeastern Massachusetts". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields. December 6, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ↑ The Greens as I Knew Them by John Morgan Bullard, 1964, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ "Early History of Network Broadcasting (1923-1926)", Report on Chain Broadcasting, Federal Communications Commission, May 1941, p. 6.

- ↑ "The Van de Graaff Generator, 1933". MIT Institute Archives & Special Collections. January 2005.

- ↑ Texas v. Florida, 306 U.S. 398 (U.S. March 13, 1939).

Further reading

- Bedell, Barbara Fortin, Colonel Edward Howland Robinson Green and the World He Created at Round Hill 2003 ISBN 0-9743731-0-9

- Lewis, Arthur H., The Day They Shook the Plum Tree. New York: Harcourt Brace. (1963); Buccaneer Books, Cutchogue, New York (1990) ISBN 0-89966-600-0

- "Hetty Green's Railroad". by Arthur H. Lewis, Railroad Magazine, October 1963, pp. 17–23