Eastern Rukum District

पूर्वी रुकुम | |

|---|---|

Mount Sisne | |

Location of the district (dark yellow) in Lumbini Province | |

| Coordinates: 28°22′N 82°22′E / 28.37°N 82.37°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Lumbini Province |

| Established | 2015 |

| Admin HQ. | Rukumkot |

| Government | |

| • Type | Coordination committee |

| • Body | DCC, Eastern Rukum |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,161.13 km2 (448.31 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 53,018 |

| • Density | 46/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+05:45 (NPT) |

| Website | dccrukumeast |

Eastern Rukum (Nepali: पूर्वी रुकुम) is a mountain district of Lumbini Province of Nepal situated along the Dhaulagiri mountain range.[1][2] It is also the only mountain district of the province with its tallest mountain Putha Hiunchuli (Dhaulagiri VII) situated in the west end of Dhaulagiri II mountain chain, at an elevation of 7,246 meters.[3] The drainage source of ancient Airavati river, one of the five sacred rivers of Buddhism, lies in the lesser Himalayas of the district.[4] With a Dhaulagiri mountain range, lakes, rich Magar culture and its political history, Eastern Rukum has been among the top travel destinations of Nepal as designated by the Government of Nepal.[5][6]

The district is known for having 52 ponds and 53 hills.[7] From 1996 to 2006, Eastern Rukum - a region with Magar majority - was one of the historical base area of the People's War of Nepal providing many foot soldiers, commanders, prominent leaders and martyrs during the war which in turn pivoted the country into a democratic Federal republic in 2008.[8] Guerilla trekking route has also been developed in the district as an adventure tourism following the past trails of the rebels in the base of Himalayas providing experiences of scenic landscapes, Dhaulagiri mountain ranges and rich Kham Magar culture.[9][10] In 2018, the district was labelled among the "fully literate" districts of the country, with a literacy rate of over 95%, showing a significant post-conflict development.[11][12] After Palpa district (53% Magar population), Eastern Rukum has the second largest Magar population in Nepal as a percentage of the total population (51% Magar population).[13]

Though successful in maintaining various levels of autonomy, independence and preservation of Kham Magar culture even during ancient and medieval Nepal, the region's structure were altered during the rule of Rana dynasty as well as during Panchayat era. Before 1975, substantial portion of Eastern Rukum was territorially merged with Palpa district during the Rana regime and with Baglung District during Panchayat.[14][15] On 20 September 2015, Eastern Rukum was created as a new district after the state's reconstruction of administrative divisions splitting Rukum District into Western Rukum and Eastern Rukum.

Etymology

The district is traditionally believed to have been named after the Hindu Goddess Rukmini, the consort of Krishna.[16]

History

Early history

Himalayas has been a melting pot of diverse tribes and cultures since antiquity. The presence of highly-rich majority Magar culture with a complex of Kham Magar language of Sino-Tibetan language family suggests its favorable growth in Eastern Rukum south of Himalayas.[17] In addition to this, being on the northern corridor of the Indian sub-continent, the region was also on the radius of the Indus valley civilization and influences of various warring tribes and empires such as Kirata Kingdom, Kushan Empire (Ancient Greek), Gupta Empire, Maurya Empire, Nanda Empire, Karkota Empire, Utpala dynasty, Tibetan Empire and Khasa Kingdom.[18] Therefore, there seems to have formed a synthesis of shamanism, Bon, Buddhism, Masto worship, and Hinduism (in the later phase) in the region over a stretch of time. After the initial Muslim conquests spanning out of Arabian lands, western and central Himalayas also served as the refuge and protection to numerous non-Muslims.[19] With east-west Dhorpatan valley south of the Himalayas, eastern Rukum was also a historic migration route and crossroad for these tribes to move eastwards.

Medieval History

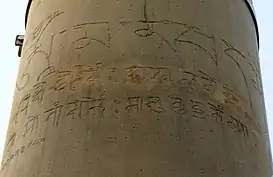

On the north of this region (present neighbour Dolpa), Buddhism hugely flourished with the arrival of a famous 8th century Buddhist master Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) and other Buddhist lamas who meditated in the region and consecrated many places.[20] Politically, after 11th century, the archeological records suggests that the region was ruled by the Khasa Kingdom (Tibetan: Ya rtse Kingdom) rulers who were predominantly oriented to shamanism and Buddhism. In their heyday, the kingdom had dominion over large portion of western Tibet and western Nepal[21] and was geographically and historically linked with Central Asia and western Tibet.[22] The initial Khasa rulers were devout Buddhists themselves, evident by a pilgrimage of King Ripumalla to Lumbini,[23] where he left an inscription on the Ashoka pillar dated around 1312 CE with six-syllable mantra of Buddhism and his wish "Om mani padme hum: May Prince Ripu Malla be long victorious". With time as contacts with the south grew stronger, Hinduism later made a stronghold among the rulers of the region. Both the western Nepalese as well as Tibetan chronicles mention same kings as their "Kings of West Tibet" as well as " Kings of Khasa Kingdom".[23]

The following list narrates the names of the Khasa kings, in Nepali and Tibetan language:

| Western Nepal Chronological list name | Tibetan Chronological list name |

|---|---|

| Nāgarāja (Nepali: नागराज), 11th century | Naga lde |

| Chaap/Cāpa (Nepali: चाप; IAST: Cāpa), son of Nāgarāja | bTsan phyug lde |

| Chapilla/Cāpilla (Nepali: चापिल्ल; IAST: Cāpilla), son of Cāpa | bKra shis lde |

| Krashichalla (Nepali: क्राशिचल्ल; IAST: Krāśicalla), son of Cāpilla | Grags btsan lde |

| Kradhichalla (Nepali: क्राधिचल्ल; IAST: Krādhicalla), son of Krāśicalla | Grags pa lde |

| Krachalla (Nepali: क्राचल्ल; IAST: Krācalla), son of Krādhicalla | - |

| Ashoka Challa (Nepali: अशोक चल्ल; IAST: Aśokacalla), son of Krācalla | A sog lde |

| Jitari Malla (Nepali: जितारी मल्ल; IAST: Jitārimalla), first son of Aśokacalla | Ji dar sMal |

| Ananda Malla (Nepali: आनन्द मल्ल; IAST: Ānandamalla), second son of Aśokacalla | A nan sMal |

| Ripu Malla (Nepali: रिपु मल्ल; IAST: Ripumalla) (1312–13), son of Ānandamalla | Ri'u sMal |

| Sangrama Malla (Nepali: संग्राम मल्ल; IAST: Saṃgrāmamalla), son of Ripumalla | San gha sMal |

| Aditya Malla (Nepali: आदित्य मल्ल; IAST: Ādityamalla), son of Jitārimalla | A jid smal |

| Kalyana Malla (Nepali: कल्याण मल्ल; IAST: Kalyāṇamalla) | Ka lan smal |

| Pratapa Malla (Nepali: प्रताप मल्ल; IAST: Pratāpamalla), son of Kalyāṇamalla | Par t'ab smal |

| Punya Malla (Nepali: पुण्य मल्ल; IAST: Puṇyamalla), | Pu ni sMal |

| Prithvi Malla (Nepali: पृथ्वी मल्ल; IAST: Pṛthvīmalla), son of Puṇyamalla | sPri ti sMal |

| Surya Malla (Nepali: सूर्य मल्ल) Son of Ripu Malla | - |

| Abhaya Malla (Nepali: अभय मल्ल), 14th century | - |

When the Khasa kingdom disintegrated, one of their descendants named Pitambar is recorded to have ruled the region after defeating the Magar King known as Bokshe Jad and the region subsequently disintegrated into further principalities in the incoming generations until their integration into modern Nepal (1777-1799) by Shah kings.[25][26]

Modern history

With the conquest of the district as a part of the national unification campaign, the region was merged with the kingdom of Nepal during the time of Bahadur Shah of Nepal and Rana Bahadur Shah (1777-1799). Before 1975, substantial eastern portion was territorially merged with Palpa district during Rana dynasty and with Baglung District or Dolpa District.[14][15]

During the centuries long Shah dynasty and Rana Dynasty rule of Nepal, numerous young women of this region were made Queens (Bada Maharani) and wives of the dynasties through royal marriages, locally known as "Dola Palne" tradition such as:[27] Queen Purna Kumari Devi,[28] the wife of a Rana Prime Minister; Queen Karma Kumari Devi, the wife of Prime Minister Dev Shumsher Jang Bahadur Rana and foster mother of Prime Minister Juddha Shumsher Jang Bahadur Rana.[27] In other cases, the marriages of royal princesses were made with the formerly ruling families of this region, for instance, the marriage of Shova Rajya Lakshmi Devi (Princess Shova Shahi of Nepal), the sister of King Birendra of Nepal and the youngest daughter of king Mahendra of Nepal. After Princess Shova Rajya Lakshmi Devi visited the birth-place of her husband in Bahunthana (Rukumkot), the name of the village was changed to "Shova."[29] These forms of royal marriages created influential feudal families in the region who were well connected with the rulers in Kathmandu by blood or marriages and the majority peasants in the districts were socially and politically sub-ordinate.

Hashish Ban of 1976

Once considered one of the most prosperous region of the western Nepalese hills, being one of the principal producers of world renowned Nepali hashish, eastern Rukum was among the heartland of legendary cannabis production providing sufficient to the outside market, even commanding premiums in India during World War II. This abundance was reflected in the dressings of local Magar women who were once wearing silver coin necklaces and gold jewelries. The plant's bark was used to make ropes, fibers to make bags and its fine threads were used in clothing and hashish was grown and collected as any other product instead of narcotics.[29]

This social affluence came to an abrupt halt in 1976 when the Government of Nepal enacted the Drug Trafficking and Abuse Act, largely from the political pressure of the United States of America and Narcotics International, lobbied by the president Richard Nixon. The Nepalese government responded with Drug Trafficking and Abuse Act banning marijuana and hashish in return for American economic aids projects (USAID) in this region - leading to numerous arrests, private land property where marijuana was grown was revoked and given back to the state and farmers were forced to eradicate their marijuana fields before the activity of USAID projects.[30] Although King Birendra made two visits in 1983 and 1988 and promised further economic aid in the region, there was a perception that the actual beneficiaries of the development aids were few elites instead of the local majority, creating further spike in inequality.[29]

Growth of Communism & Federalism

After the bitterness arising with the implications of subsequent disruptive state actions, the peasants of the districts began to resonate with the communist parties who were advocating against social and political injustice.[30][31] Researchers point out that due to lasting feudalism, aristocracy, social inequality within the district, there was a growing dissatisfaction of the larger public towards the elites.[32] As a result, eastern Rukum became one of the earliest communist stronghold of the country during the 20th century.[8] Not surprisingly, it also became the heartland of Nepalese Civil War (Maoist revolution) and the district came to be known as a Magar homeland of the war against land inequality, ethnic inequality, feudalism and aristocracy from 1996 till 2006. The region became a historical base area of the People's War of Nepal and provided many foot soldiers, commanders, prominent leaders and martyrs during the war, ultimately pivoting the country into a democratic Federal republic in 2008 with the end of 240-year-old monarchy.[8][33]

Division & Demographics

The total area of Eastern Rukum District is 1,161.13 square kilometres (448.31 sq mi) and total population of this district as of 2011 Nepal census is 53,018 individuals.[34][35] Rukumkot is the interim headquarter of the district. There was a decision of government to relocate the district headquarter from Rukumkot to Golkhada, Kol, Putha Uttarganga, albeit not finalized until now.[36]

The district is divided into three rural municipalities:

| Name | Nepali | Population (2011) | Area (km2) | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhume | भूमे | 18,589 | 273.67 | 68 |

| Putha Uttarganga | पुथा उत्तरगंगा | 17,932 | 560.34 | 32 |

| Sisne | सिस्ने | 16,497 | 327.12 | 50 |

Demographics

At the time of the 2011 Nepal census, Eastern Rukum District had a population of 53,184.

As their first language, 69.1% spoke Nepali, 19.1% Magar, 10.7% Kham, 0.7% Gurung, 0.1% Doteli and 0.2% other languages as their first language.[37]

Ethnicity/caste: 50.7% were Magar, 19.2% Chhetri, 17.3% Kami, 4.1% Thakuri, 3.2% Damai/Dholi, 1.7% Hill Brahmin, 1.3% Gurung, 0.8% Newar, 0.5% Sarki, 0.3% Badi, 0.2% Chhantyal, 0.2% Thakali, 0.1% Chamar/Harijan/Ram, 0.1% other Dalit, 0.1% Kurmi, 0.1% Sanyasi/Dasnami and 0.2% others.[38]

Religion: 91.8% were Hindu, 3.7% Christian, 2.2% Buddhist, 0.1% Prakriti and 2.1% others.[39]

Literacy: 53.9% could read and write, 3.0% could only read and 43.1% could neither read nor write.[40]

Magars make up the majority of the population in Eastern Rukum.[13] After Palpa district (53% Magar population), Eastern Rukum has the second-largest Magar population in Nepal as a percentage of the total population (51%), followed by Rolpa (43%). The table highlights the demographics of the district (National Data Profile:2020).[13]

| Demographics | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Magar | 26,860 | 50.66 |

| Chhetri | 10,200 | 19.24 |

| Kami | 9,149 | 17.26 |

| Thakuri | 2,195 | 4.14 |

| Damai | 1,684 | 3.18 |

| Hill Brahmin | 883 | 1.67 |

| Gurung | 692 | 1.31 |

| Newar | 399 | 0.75 |

| Sarki | 271 | 0.51 |

| Others | 685 | 1.28 |

Climate & Geography

Eastern Rukum district is the northernmost part of Lumbini Province, and its only mountain district. Most of the district is drained by west-flowing tributaries such as Uttar Ganga draining Dhorpatan Valley and to the north of that the Sani Bheri draining southern slopes of the western Dhaulagiri Himalaya. Elevation reaches 6,000 meters in the Dhaulagiri with a range of climates from sub-tropical to perpetual snow and ice. Agricultural use ranges from irrigated rice cultivation through upland cultivation of maize, barley, wheat, potatoes and fruit, to sub-alpine and alpine pasturage reaching about 4,500 meters.

There are six climates:

| Climate Zone | Elevation Range |

|---|---|

| Upper Tropical | 300 to 1,000 meters |

| Subtropical | 1,000 to 2,000 meters |

| Temperate | 2,000 to 3,000 meters |

| Subalpine | 3,000 to 4,000 meters |

| Alpine | 4,000 to 5,000 meters |

| Nival | above 5,000 meters |

Dhorpatan Reserve

A large reserve area named Dhorpatan Reserve in the district was declared in 1987 with subsequent objective of protection and management of high altitude ecosystem in western Nepal. The reserve extends along the Dhaulagiri Himalayan Range of eastern Rukum, Myagdi and Baglung and covers 1325 square kilometers. Putha, Churen and Gurja Himal extend over the northern boundary of the reserve.[41] Eastern Rukum itself occupies over sixty percentage territory of the reserve.

Dhaulagiri Mountains

Dhaulagiri mountain range extends from north-west to north-east of Eastern Rukum district and then continues eastward to its highest elevation, Dhaulagiri I, the 7th highest mountain in the world. The Kali Gandaki river gorge separates Dhaulagiri range and Annapurna range forming two mountain ranges in western Nepal.[42]

All along the Dhaulagiri range, the prominent mountains in the district are Mt. Putha Hiunchuli (Dhaulagiri VII) and Mount Sisne. Mount Putha is also the tallest mountain of Lumbini Province situated in the west end of Dhaulagiri II mountain chain, at an elevation of 7,246 meters. It was first climbed in 1954 by J. O. M. Roberts and Ang Nyima Sherpa.[43]

Another prominent mountain is Mount Sisne at the north. Locally known as Mount Sisne or Murkatta Himal, the mountain has an elevation of 5,849 meters. Mount Sisne was frequently featured in the literatures of civil war, as a symbol of the people's revolution and became an iconic landmark to revolutionaries during the 1996–2006 Nepal Civil War. In 2013, the mountain was first successfully ascended by a Nepalese expedition led by Man Bahadur Khatri.[44]

| S/N | Mountains | Elevation

(meters) |

Range | Additional

Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mount Putha I | 7,246 | Dhaulagiri Range | First ascent in 1954 by J.O.M

Roberts and Ang Nyima Sherpa |

| 2 | Mount Putha II (Putha shoulder) | 6,598 | Dhaulagiri Range | |

| 3 | Mount Dogari (South) | 6,315 | Dhaulagiri Range | |

| 4 | Mount Samjang | 5,924 | Dhaulagiri Range | |

| 5 | Hiunchuli Patan | 5,916 | Dhaulagiri Range | |

| 6 | Mount Nimku | 5,864 | Dhaulagiri Range | |

| 7 | Mount Sisne II | 5,854 | Dhaulagiri Range | |

| 8 | Mount Sisne I | 5,849 | Dhaulagiri Range | Date of first ascent:

26/05/2021 AD[46] |

Water System

Most of the district is drained by west-flowing tributaries such as Uttar Ganga draining Dhorpatan Valley and to the north of that the Sani Bheri draining southern slopes of the western Dhaulagiri Himalaya.

West Rapti river has its source in Eastern Rukum in the Mahabharata range of the lesser himalayas.[4] The river drains in Nepal and into Uttar Pradesh state in India before joining Ghaghara which ultimately joins the Ganges. The West Rapti river is also associated with the ethnic groups of Nepal – Kham Magar in the highlands and Tharu in the Inner Terai. The river has also been associated with the ancient river Airavati (also known as Aciravati /Achirvati) and as Eravai in Jainism.[47][48] In Buddhism, the ancient city of Sravasti was situated in the western bank of Achirvati where the Buddha spent most of his post-enlightenment life.[48]

Among many lakes, Rukmini Lake has been the centerpeice in the district. Named after Rukmini, the consort of Krishna, Rukmini Lake is also known as Lotus Lake (Nepali: Kamal Taal) because of its fullness with lotus flowers (Nelumbo nucifera). The lake holds a religious and sacred importance to the locals due to which huge gathering occurs during the festivals of Maha Shivaratri, Dashain, Maghe Sankranti and Haritalika Teej.

Culture & Language

The presence of highly-rich majority Magar culture with a complex of Kham Magar language of Sino-Tibetan language family suggests its preserved development in Eastern Rukum, on the south western flank of the Dhaulagiri massif.[17] Traditionally found living in the high valleys (2,000–2,500 m altitude), Kham Magars constitute a specific ethno-linguistic community of the Magar people within the 4 northern sub-tribes: Bhuda (Bura), Gharti, Rokha and Pun and have retained their own indigenous Kham language.[49][50] Kham Magars maintain permanent villages but are travelling extensively with their cattles. Animistic in their religious approach to life in nature, shamanism is prevalent among them with elements of earth worship, forest worship, water worship and weather worship.

Among the Kham Magars of Eastern Rukum, a peculiar form of land worship (known as Bhumi Puja) takes a form of a folk dance locally known as Bhume Naach (Earth dance) which is performed around a fire, representing Earth as a mother and protector. The dance normally takes place from mid-May to mid-June. The geometrical pattern of this dance has men dancing in the center and women dancers enveloping them - the outer circle of women symbolising the mother and protection to the community. Twenty-two steps per song are performed in harmony, conveying a message of gratitude to Earth as a source of protection.[51]

Demographically: 69.10% speak Nepali, 19.08% Magar and 10.69% Kham as their main languages at home.[13]

| Languages | Percentages |

|---|---|

| Nepali | 69.10% |

| Magar | 19.08% |

| Kham Magar | 10.69% |

Economy

Electricity

As a district with high hydro-electricity potential due to down streaming rivers and plenty of water bodies, there have been efforts to maximise energy potential in the district. With this objective, 27 small-to-medium scale hydro-power stations have been established producing 1,210 KW of electricity.[52] The district's largest hydro-power station, run-of-river type, of 5 MW is still under construction with a cost of Rs 1 Billion.[53] In addition to these stations, there are existing water mills and solar systems to garner electricity.

| Means of Production | Numbers |

|---|---|

| Small-to-medium scale hydro-power stations | 27 |

| Large scale hydropower, 5MW | 1 |

| Traditional water mills | 127 |

| Refined water mills | 9 |

| Solar systems | 7440 |

Agriculture and rare medicinal herbs

The six-climatic mixture of upper tropical, sub-tropical, alpine, sub-alpine, temperate and nival climates in the district have given way to the production of radish, potato, Pidalu, onion, rayo, garlic, turmeric, ginger, tomato, persimmon, golbheda, ramatoria, bitter gourd, brinjal, chillies, peas, carrot, cauliflower, cabbage, cucumber, squash, bananas, mango, orange, lemon, season, apple, pear, arubkhada, okhar etc. In addition to these vegetables and fruits, the medicinal herbs such as Yarsagumba, Panchaole, Kurilo, Timur, Cinnamon, Gurjo, Katuki, Pangar, Badalpate, Bojo, Harro, Amla, Padamchal, Satuwa, Halhale, Kumkum, Chiraito, Jatamasi, Bhalayo etc. are procured.[54] The most famous among them, Yarsagumba (known as Ophiocordyceps Sinensis) is classified as a medicinal mushroom with a long usage in the Himalayan region, Tibetan and Chinese medicine. In addition, the crops such as paddy, wheat, maize, millet, barley, uva, fapar etc. are grown in their season and constitute the staple food diet as well.

Minerals

A Himalayan sub-region, the region has been found conducive for the mining of copper, glass, coal, iron, chalk, shilajita and Sulphur. In addition to this, non-metallic ore such as Dolomite have been discovered.

Nepalese paper

As a paper producing district, due to the availability of Lokta plants, the fibrous inner bark of these high altitude evergreen shrubs are used to produce paper in Eastern Rukum. These papers are hand-made and produced in batches, whereby each batch processes about 12.5 kg of raw materials. As one of the rare Nepalese products, all the supply chain elements are based on local resources which are then ultimately made into paper products and exported to Europe and North America.[55]

The chief exports from the district are vegetables, seeds, Nepalese paper, blankets, threads and mineral.[26]

Education

Post federalism in Nepal, the district is now classified as one of the fully literate districts of the country, with over 95% of literacy rate.[12]

Tourism

In recent years, Eastern Rukum has become a tourist destination of the country, also reflected in the Government of Nepal's official designation.[5] The trekking agencies usually provide trekking routes with a focus on Dhaulagiri mountain range and Magar villages of Eastern Rukum.

Guerilla Trek

Nepal Tourism Board has designated official trekking route called Guerilla Trek which is an tourism adventure-track following the trails of guerillas (Maoist revolutionaries) during the ten-year war (Nepalese Civil War) against the royal government, in their rebel heartland in the majority Magars villages. Trekkers can retrace the route of the fighters in this district as well as neighbouring northern Rolpa District, Baglung District and Myagdi District and experience traditional Magar culture.[56]

Other important tracks of the route are Chunwang, the landmark meeting place of the party leadership in eastern Rukum and Thabang (6480 ft, 1975 m), the cradle of the war of Rolpa where the Maoists had almost unanimous support and which suffered some of the heaviest fighting during the war.[10]

Gateway to Dolpa

Often considered a gateway to Dolpa, the Jangla Pass at 4,538 meters is the edge of the Dhorpatan Reserve and provides a passage to Dolpa.[57] Dolpa, a district hidden from globalisation, is more oriented to Tibetan Buddhism and is full of hidden valleys and ancient Buddhist shrines some of whom are associated with 8th century master Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava). A reminiscence of ancient Tibet, Dolpo is still monitored and a pass is required for the tourists.

Kham Magar Culture

Perhaps due to relative isolation in high altitudes, Magars in eastern Rukum have been able to retain their indigenous language and cultures which have become a center point of attraction. The peculiarly designed houses and their festivals are peculiar, such as the Bhume Naach (Earth Dance) which is performed around a fire, representing Earth as a mother and protector. The dance normally takes place from mid-May to mid-June. Men dance on the center and the women dancers encircle them - the outer circle of women symbolising the mother and protection to the community as well as gratitude to mother earth.[51]

See also

References

- ↑ "DNPWC". Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ↑ "कान्छो जिल्लाको तोतेबोलीः किन टुक्रियो पूर्वी रुकुम ?". Online Khabar. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "रुकुम (पूर्वी भाग) जि.स.स". dccrukumeast.gov.np. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- 1 2 Singh, P. (2016). "Flood and its relationship to developmental activities in Rapti river basin, Gorakhpur". International Journal of Scientific & Innovative Research Studies: 26–35.

- 1 2 "Visit Nepal 2020 | Destinations for visit Nepal 2020". Nepal Guide Treks & Expedition - Hiking & Peak Climbing Agency. 5 January 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "Rukum : "Virgin land - a new tourism destination in Nepal"". Himalayan Mentor. 30 June 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ↑ "Chhipridaha lake in Rukum (East) on the verge of extinction". kathmandupost.com. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- 1 2 3 de Sales, Anne (2009). "From ancestral conflicts to local empowerment: two narratives from a Nepalese community". Dialectical Anthropology. 33 (3/4): 365–381. doi:10.1007/s10624-009-9136-3. ISSN 0304-4092. JSTOR 29790894. S2CID 145500590.

- ↑ "RAOnline Nepal: Trekkings in Nepal - New Trekking routes in Nepal - Guerrilla tourist trail launched". www.raon.ch. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- 1 2 "The Guerilla Trek". ECS NEPAL. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "Kathmandu becomes 55th fully literate district". Khabarhub. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- 1 2 "Total Literate Districts of Nepal". Gyan Park › A Genuine Resource. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "NepalMap profile: Rukum East". NepalMap. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- 1 2 RUKUM, TAKASERA EASTERN (31 January 2018). "विकटता र निकटता ……". Medium. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- 1 2 "रुकुमपूर्व जिल्लाको सदरमुकाम गोल्खाडा नै हुनुपर्ने माग". Sansar News- Online for Global Nepali. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ Bhusal, Suresh (15 April 2020). "रुकुम पूर्व East Rukum". चिनारी नेपाल. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- 1 2 de Sales, Anne (20 March 2019). "Kham Magar: Fact Sheet". Brill's Encyclopedia of the Religions of the Indigenous People of South Asia Online.

- ↑ "A". personal.carthage.edu. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Nepal - Caste and Ethnicity". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Monasteries and Gompas in Dolpo". Himalayan Companion Treks and Expedition. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ "King Ripumalla - ruler of the Khasa Malla kingdom". tibetmuseum.app. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ↑ Dhungel, Ramesh (2 July 2010). "Understanding Nepali History in the Context of Changing Political Situation". CNAS Journal. 37.

- 1 2 "Ian Alsop: The Metal Sculpture of the Khasa Mallas". www.asianart.com. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ↑ Tucci, Giuseppe (1956). Preliminary report on two scientific expeditions in Nepal.

- ↑ "रुकुमकोट. नेपालको मध्यपश्चिमाञ्चल विकास क्षेत्रको राप्ती अञ्चल,पुर्वी रुकुम मा अवस्थित एक सुन्दर उपत्यकामा अवस्थीत शहरउन्मुख गाँउ हो । नेपालको मध्य-पश्चिम क्षेत". ne.freejournal.org (in Nepali). Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- 1 2 "संक्षिप्त परिचय : रुकुम जि.स.स". dccrukumwest.gov.np. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- 1 2 "THE RANI FROM RUKUM - Think Research Expose | Think Research Expose". Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "Rukumkot- Town of ponds and hills". Nepal Travel Guide. 30 May 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 Western Nepal conflict assessment. United States Agency for International Development. 2003.

- 1 2 Paulson, Julia (16 May 2011). Education, Conflict and Development. Symposium Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-873927-46-5.

- ↑ Zharkevich, Ina (9 May 2019). Maoist People's War and the Revolution of Everyday Life in Nepal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-60038-5.

- ↑ Shah, Alpa; Pettigrew, Judith (11 December 2009). "Windows into a revolution: ethnographies of Maoism in South Asia". Dialectical Anthropology. 33 (3): 225. doi:10.1007/s10624-009-9142-5. hdl:10344/3890. ISSN 1573-0786.

- ↑ Monk, Katie (9 June 2008). "Nepal hails a new republic". the Guardian. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ↑ "स्थानीय तहहरुको विवरण" [Details of local level body]. www.mofald.gov.np (in Nepali). Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development (Nepal). Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ↑ "CITY POPULATION– statistics, maps & charts". www.citypopulation.de. 8 October 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Decision on East Rukum HQ stayed". www.thehimalayantimes.com. The Himalayan Times. 2 February 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ↑ NepalMap Language

- ↑ NepalMap Caste

- ↑ NepalMap Religion

- ↑ NepalMap Literacy

- ↑ "Dhorpatan Brochure 2019" (PDF). 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2021.

- ↑ "Dhaulagiri | mountains, Nepal". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ↑ "Putha Hiunchuli Climbing". www.asianhikingteam.com. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "Sisne Climbing | Western Nepal Treks". www.westernnepaltreks.com. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "Nepal Himal Peak Profile". nepalhimalpeakprofile.org. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ↑ "Sisne". nepalhimalpeakprofile.org. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ↑ Kapoor, Subodh (2002). Encyclopaedia of Ancient Indian Geography. Cosmo Publications. ISBN 978-81-7755-298-0.

- 1 2 "The Five Rivers of the Buddhists". ccbs.ntu.edu.tw. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ↑ de Sales, Anne (20 March 2019), "Kham Magar: Fact Sheet", Brill’s Encyclopedia of the Religions of the Indigenous People of South Asia Online, Brill, retrieved 20 October 2021

- ↑ "Siberian shamanistic traditions among the Kham Magar of Nepal | HimalDoc". lib.icimod.org. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- 1 2 Thabang Bhume (भुमे नाच)- Magar Festival in Nepal (in Russian), 20 October 2019, retrieved 20 October 2021

- ↑ "जल, जडीबुटी र पर्यटनमा धनी रुकुमपूर्व". Radio Purbi Rukum. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ↑ "Construction of Rukumgad Hydropower Commencing from mid-November". www.newbusinessage.com. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ↑ "जिल्लाको संक्षिप्त परिचय : रुकुम (पूर्वी भाग) जि.स.स". dccrukumeast.gov.np. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ↑ Handmade paper in Nepal. Deutsche Gesellschaft Fur Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH. 2007.

- ↑ Rana, Surendra (2018). Guerrilla Trail: A Tourism Product in the Maoist Rebel's Footsteps. Projects: Reintegration of ex-combatantsDark Tourism in NepalPeace building in Nepal.

- ↑ "Reminiscing Dolpa". ECS NEPAL. Retrieved 21 October 2021.