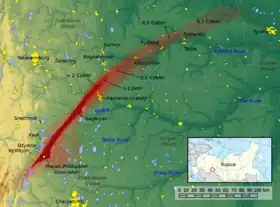

Map of the East Urals Radioactive Trace (EURT): area contaminated by the Kyshtym disaster. | |

| Native name | Кыштымская авария |

|---|---|

| Date | 29 September 1957 |

| Time | 11:22 UTC |

| Location | Mayak, Chelyabinsk-40, Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Coordinates | 55°42′45″N 60°50′53″E / 55.71250°N 60.84806°E |

| Also known as | Mayak disaster or Ozyorsk disaster |

| Type | Nuclear accident |

| Outcome | INES Level 6 (serious accident) |

| Casualties | |

| 270,000 affected. 10,000–12,000 evacuated. At least 200 people died of radiation sickness[1][2] 66 diagnosed cases of chronic radiation syndrome[3] | |

The Kyshtym disaster, sometimes referred to as the Mayak disaster or Ozyorsk disaster in newer sources, was a radioactive contamination accident that occurred on 29 September 1957 at Mayak, a plutonium production site for nuclear weapons and nuclear fuel reprocessing plant located in the closed city of Chelyabinsk-40 (now Ozyorsk) in Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union.

The disaster is the second worst nuclear incident by radioactivity released, after the Chernobyl disaster. It is the only disaster classified as Level 6 on the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES),[4] which ranks by population impact, making it the third-worst after the two Level 7 events: the Chernobyl disaster, which resulted in the evacuation of 335,000 people, and the Fukushima Daiichi disaster, which resulted in the evacuation of 154,000 people. At least 22 villages were exposed to radiation from the Kyshtym disaster, with a total population of around 10,000 people evacuated. Some were evacuated after a week, but it took almost two years for evacuations to occur at other sites.[5]

The disaster spread hot particles over more than 52,000 square kilometres (20,000 sq mi), where at least 270,000 people lived.[6] Since Chelyabinsk-40 (later renamed Chelyabinsk-65 until 1994) was not marked on maps, the disaster was named after Kyshtym, the nearest known town.

Background

After World War II, the Soviet Union lagged behind the United States in the development of nuclear weapons, so its government started a rapid research and development program to produce a sufficient amount of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium. The Mayak plant was built in haste between 1945 and 1948. Gaps in physicists’ knowledge about nuclear physics at the time made it difficult to judge the safety of many decisions.

Environmental concerns were secondary during the early development stage. Initially Mayak dumped high-level radioactive waste into a nearby river, which flowed to the river Ob, flowing farther downstream to the Arctic Ocean. All six reactors were on Lake Kyzyltash and used an open-cycle cooling system, discharging contaminated water directly back into the lake.[7] When Lake Kyzyltash quickly became contaminated, Lake Karachay was used for open-air storage, keeping the contamination a slight distance from the reactors but soon making Lake Karachay the "most-polluted spot on Earth".[8][9][10]

A storage facility for liquid nuclear waste was added around 1953. It consisted of steel tanks mounted in a concrete base, 8.2 meters (27 ft) underground. Because of the high level of radioactivity, the waste was heating itself through decay heat (though a chain reaction was not possible). For that reason, a cooler was built around each bank, containing twenty tanks. Facilities for monitoring operation of the coolers and the content of the tanks were inadequate.[11] The accident involved waste from the sodium uranyl acetate process used by the early Soviet nuclear industry to recover plutonium from irradiated fuel.[12] The acetate process was a special process never used in the West; the idea is to dissolve the fuel in nitric acid, alter the oxidation state of the plutonium, and then add acetic acid and base. This would convert the uranium and plutonium into a solid acetate salt.

Explosion

In 1957, the Mayak plant was the site of a major disaster, one of many other such accidents, releasing more radioactive contamination than the Chernobyl disaster. An improperly stored underground tank of high-level liquid nuclear waste exploded, contaminating thousands of square kilometers of land, now known as the Eastern Ural Radioactive Trace (EURT). The matter was covered up, and few either inside or outside the Soviet Union were aware of the full scope of the disaster until 1980.[13]

Before the 1957 accident, much of the waste was dumped into the Techa River, which severely contaminated it and residents of dozens of riverside villages such as Muslyumovo, who relied on the river as their sole source of drinking, washing, and bathing water. After the 1957 accident, dumping in the Techa River officially ceased, but the waste material was left in convenient shallow lakes near the plant instead, of which 7 have been officially identified. Of particular concern is Lake Karachay, the closest lake to the plant (now notorious as "the most contaminated place on Earth"[8]) where roughly 4.4 exabecquerels of high-level liquid waste (75–90% of the total radioactivity released by Chernobyl) was dumped and concentrated in the shallow 45-hectare (0.45 km2; 110-acre) lake[14] over several decades.

On September 29, 1957, Sunday, 4:22 pm, an explosion occurred within stainless steel containers located in a concrete canyon 8.2 m (27 feet) deep used to store high-level waste. The explosion completely destroyed one of the containers, out of 14 total containers ("cans") in the canyon. The explosion was caused because the cooling system in one of the tanks at Mayak, containing about 70–80 tons of liquid radioactive waste, failed and was not repaired. The temperature in it started to rise, resulting in evaporation and a chemical explosion of the dried waste, consisting mainly of ammonium nitrate and acetates (see ammonium nitrate/fuel oil). The explosion was estimated to have had a force of at least 70 tons of TNT.[15] The explosion lifted a concrete slab weighing 160 tons, and a brick wall was destroyed in a building located 200 meters (660 ft) from the explosion site. A tenth of the radioactive substances were lifted into the air. After the explosion, a column of smoke and dust rose to a kilometre high; the dust flickered with an orange-red light and settled on buildings and people. The rest of the waste discarded from the tank remained at the industrial site.

The workers at Ozyorsk and the Mayak plant did not immediately notice the contaminated streets, canteens, shops, schools, and kindergartens. In the first hours after the explosion, radioactive substances were brought into the city on the wheels of cars and buses, as well as on the clothes and shoes of industrial workers. After the blast at the facilities of the chemical plant, dosimetrists noted a sharp increase in the background radiation. Many industrial buildings, vehicles, concrete structures, and railways were contaminated. The most polluted were the central city street Lenin, especially when entering the city from the industrial site, and Shkolnaya street, where the management of the plant lived. Subsequently, the city administration imposed measures to stop the spreading of contamination. It was forbidden to enter the city from industrial sites in cars and buses. Site workers at the checkpoint got off the buses and passed the checkpoint. This requirement extended to everyone, regardless of rank and official position. Shoes were washed on flowing trays. The city was intentionally constructed to be upwind from the Mayak plant given the prevailing winds, so most of the radioactive material drifted away from, rather than towards, Ozyorsk.[16][17]

There were no immediate reported casualties as a result of the explosion, however, and the scope and nature of the disaster were covered up both internally and abroad.[18] Even as late as 1982, Los Alamos published a report investigating claims that the release was actually caused by a weapons test gone awry.[19] The disaster is estimated to have released 20 MCi (800 PBq) of radioactivity. Most of this contamination settled out near the site of the accident and contributed to the pollution of the Techa River, but a plume containing 2 MCi (80 PBq) of radionuclides spread out over hundreds of kilometers.[20] Previously contaminated areas within the affected area include the Techa river, which had previously received 2.75 MCi (100 PBq) of deliberately dumped waste, and Lake Karachay, which had received 120 MCi (4,000 PBq).[10]

In the next ten to eleven hours, the radioactive cloud moved towards the north-east, reaching 300–350 km (190–220 mi) from the accident. The fallout of the cloud resulted in long-term contamination of an area of 800 to 20,000 km2 (300 to 8,000 sq mi), depending on what contamination level is considered significant, primarily with caesium-137 and strontium-90.[10] The land area thus exposed to radioactive contamination was termed the "East Ural Radioactive Trace" (EURT). About 270,000 people inhabited this area. Fields, pastures, reservoirs, and forests in the area were polluted and rendered unsuitable for further use.

In a memo addressed to the Central Committee of the CPSU, Industry Minister E.P. Slavsky wrote: "Investigating the causes of the accident on the spot, the commission believes that the main culprits of this incident are the head of the radiochemical plant and the chief engineer of this plant, who committed a gross violation of the technological regulations for the operation of storage of radioactive solutions". In the order for the Ministry of Medium Machine Building, signed by E.P. Slavsky, it was noted that the reason for the explosion was insufficient cooling of the container, which allowed it to increase in temperature to the point its contents reacted with each other and exploded. This was later confirmed in experiments carried out by the Central Factory Laboratory (CPL). The director of the plant M. A. Demyanovich took all the blame for the accident, for which he was relieved of his duties as director.[17]

Evacuations

| Village | Population | Evacuation time (days) | Mean effective dose equivalent (mSv) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berdyanish | 421 | 7–17 | 520 |

| Satlykovo | 219 | 7–14 | 520 |

| Galikayevo | 329 | 7–14 | 520 |

| Rus. Karabolka | 458 | 250 | 440 |

| Alabuga | 486 | 255 | 120 |

| Yugo-Konevo | 2,045 | 250 | 120 |

| Gorny | 472 | 250 | 120 |

| Igish | 223 | 250 | 120 |

| Troshkovo | 81 | 250 | 120 |

| Boyovka | 573 | 330 | 40 |

| Melnikovo | 183 | 330 | 40 |

| Fadino | 266 | 330 | 40 |

| Gusevo | 331 | 330 | 40 |

| Mal. Shaburovo | 75 | 330 | 40 |

| Skorinovo | 170 | 330 | 40 |

| Bryukhanovo | 89 | 330 | 40 |

| Krivosheino | 372 | 670 | 40 |

| Metlino | 631 | 670 | 40 |

| Tygish | 441 | 670 | 40 |

| Chetyrkino | 278 | 670 | 42 |

| Klyukino | 346 | 670 | 40 |

| Kirpichiki | 160 | 7–14 | 5 |

Aftermath

Because of the secrecy surrounding Mayak, the populations of affected areas were not initially informed of the accident. A week later, on 6 October 1957, an operation for evacuating 10,000 people from the affected area started, still without giving an explanation of the reasons for evacuation.

Vague reports of a "catastrophic accident" causing "radioactive fallout over the Soviet and many neighboring states" began appearing in the Western press between 13 and 14 April 1958, and the first details emerged in the Viennese paper Die Presse on 17 March 1959.[19][21] But it was only eighteen years later, in 1976, that Soviet dissident Zhores Medvedev made the nature and extent of the disaster known to the world.[22][23] Medvedev's description of the disaster in the New Scientist was initially derided by Western nuclear industry sources, but the core of his story was soon confirmed by Professor Lev Tumerman, former head of the Biophysics Laboratory at the Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology in Moscow.[24]

The true number of fatalities remains uncertain because radiation-induced cancer is very often clinically indistinguishable from any other cancer, and its incidence rate can be measured only through epidemiological studies. Recent epidemiological studies suggest that around 49 to 55 cancer deaths among riverside residents can be associated with radiation exposure.[25] This would include the effects of all radioactive releases into the river, 98% of which happened long before the 1957 accident, but it would not include the effects of the airborne plume that was carried north-east.[26] The area closest to the accident produced 66 diagnosed cases of chronic radiation syndrome, providing the bulk of the data about this condition.[3]

To reduce the spread of radioactive contamination after the accident, contaminated soil was excavated and stockpiled in fenced enclosures that were called "graveyards of the earth".[27] The Soviet government in 1968 disguised the EURT area by creating the East Ural Nature Reserve, which prohibited any unauthorised access to the affected area.

According to Gyorgy,[28] who invoked the Freedom of Information Act to gain access to the relevant Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) files, the CIA had known of the 1957 Mayak accident since 1959, but kept it secret to prevent adverse consequences for the fledgling American nuclear industry.[29] Starting in 1989, several years after the Chernobyl disaster, the Soviet government gradually declassified documents pertaining to the incident at Mayak.[30][31]

Current situation

The level of radiation in Ozyorsk, at about 0.1 mSv a year,[32] is harmless,[33] but a 2002 study showed the Mayak nuclear workers and the Techa riverside population are still affected.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ Salkova, Alla (27 September 2017). "Кыштымская авария: катастрофа под видом северного сияния" [Kyshtym accident: a catastrophe under the guise of northern lights]. Gazeta.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ "Kyshtym Nuclear Disaster – 1957". Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- 1 2 Gusev, Guskova & Mettler 2001, pp. 15–29

- ↑ Lollino et al. 2014 p. 192

- ↑ Kostyuchenko & Krestinina 1994, pp. 119–125

- ↑ Webb, Grayson (12 November 2015). "The Kyshtym Disaster: The Largest Nuclear Disaster You've Never Heard Of". Mental Floss. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ↑ Schlager 1994

- 1 2 Lenssen, "Nuclear Waste: The Problem that Won't Go Away", Worldwatch Institute, Washington, D.C., 1991: 15.

- ↑ Andrea Pelleschi (2013). Russia. ABDO Publishing Company. ISBN 9781614808787.

- 1 2 3 "Chelyabinsk-65".

- ↑ "Conclusions of government commission" (in Russian).

- ↑ Foreman, Mark R. St J. (2018). "Reactor accident chemistry an update". Cogent Chemistry. 4 (1). doi:10.1080/23312009.2018.1450944.

- ↑ "The Kyshtym accident, 29th September 1957" (PDF), Stråleverninfo, Norwegian Radiation Protection Authority, 28 September 2007, ISSN 0806-895X

- ↑ Tabak, Faruk (2015). Allies As Rivals: The U.S., Europe and Japan in a Changing World-system. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317263968. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

Lake Karachay, a shallow pond about 45 hectares in area.

- ↑ "Kyshtym disaster | Causes, Concealment, Revelation, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ↑ Melnikova, N. V.; Artemov, N. T.; Bedel, A. E.; Voloshin, N. P.; Mikheev, M. V. (2018). The History Of Interaction Between Nuclear Energy And Society In Russia (PDF). Translated by Govorukhina, T. V. Ekaterinberg: Ural University Press. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- 1 2 "Accident at the lighthouse in 1957". IK-PTZ. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

• Volobuev, P.V.; et al. (2000). Восточно-Уральский радиоактивный след: проблемы реабилитации населения и территорий Свердловской области [East Ural radioactive trace: Problems of rehabilitation of the population and territories of the Sverdlovsk region] (in Russian). Yekaterinburg: Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 5-7691-1021-X. - ↑ Newtan 2007, pp. 237–240

- 1 2 Soran & Stillman 1982.

- ↑ Kabakchi & Putilov 1995, pp. 46–50

- ↑ Barry, John; Frankland, E. Gene (25 February 2014). International Encyclopedia of Environmental Politics. Routledge. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-135-55396-8.

- ↑ Medvedev 1976, pp. 264–267

- ↑ Medvedev 1980

- ↑ "The Nuclear Disaster They Didn't Want To Tell You About". Andrews Cockburn. Esquire Magazine. 26 April 1978.

- ↑ Standring, Dowdall & Strand 2009

- 1 2 Kellerer 2002, pp. 307–316

- ↑ Trabalka 1979

- ↑ Gyorgy 1979

- ↑ Newtan 2007, pp. 237–240

- ↑ "The decision of Nikipelov Commission" (in Russian).

- ↑ Smith 1989

- ↑ Suslova, KG; Romanov, SA; Efimov, AV; Sokolova, AB; Sneve, M; Smith, G (2015). "Journal of Radiological Protection, December 2015, pp. 789–818". Journal of Radiological Protection. 35 (4): 789–818. doi:10.1088/0952-4746/35/4/789. PMID 26485118. S2CID 26682900.

- ↑ "Natural Radioactivity". radioactivity.eu.com.

In France, the exposure dose is 2.4 millisieverts per person per year, ...

Bibliography

- Lollino, Giorgio; Arattano, Massimo; Giardino, Marco; Oliveira, Ricardo; Silvia, Peppoloni, eds. (2014). Engineering Geology for Society and Territory: Education, professional ethics and public recognition of engineering geology, Volume 7. International Association for Engineering Geology and the Environment (IAEG). International Congress. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-09303-1.

- Schlager, Neil (1994). When Technology Fails. Detroit: Gale Research. ISBN 978-0-8103-8908-3.

- Kabakchi, S. A.; Putilov, A. V. (January 1995). "Data Analysis and Physicochemical Modeling of the Radiation Accident in the Southern Urals in 1957". Atomnaya Energiya. Moscow (1). doi:10.1007/BF02408278. S2CID 93225060. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015.

- Dicus, Greta Joy (16 January 1997). "Joint American-Russian Radiation Health Effects Research". United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- Kostyuchenko, V.A.; Krestinina, L.Yu. (1994). "Long-term irradiation effects in the population evacuated from the East-Urals radioactive trace area". Science of the Total Environment. 142 (1–2): 119–25. Bibcode:1994ScTEn.142..119K. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(94)90080-9. PMID 8178130.

- Medvedev, Zhores A. (4 November 1976). "Two Decades of Dissidence". New Scientist.

- Medvedev, Zhores A. (1980). Nuclear disaster in the Urals translated by George Saunders. 1st Vintage Books ed. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-394-74445-2. (c1979)

- Pollock, Richard (1978). "Soviets Experience Nuclear Accident". Critical Mass Journal.

- Soran, Diane M.; Stillman, Danny B. (January 1982). An Analysis of the Alleged Kyshtym Disaster (Technical report). Los Alamos National Laboratory. doi:10.2172/5254763. OSTI 5254763. LA–9217–MS – via UNT Digital Library.

- Standring, William J.F.; Dowdall, Mark; Strand, Per (2009). "Overview of Dose Assessment Developments and the Health of Riverside Residents Close to the "Mayak" PA Facilities, Russia". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (1): 174–199. doi:10.3390/ijerph6010174. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 2672329. PMID 19440276.

- Kellerer, AM. (2002). "The Southern Urals radiation studies. A reappraisal of the current status". Radiation and Environmental Biophysics. 41 (4): 307–16. doi:10.1007/s00411-002-0168-1. ISSN 0301-634X. PMID 12541078. S2CID 20154520.

- Gusev, Igor A.; Guskova, Angelina Konstantinovna; Mettler, Fred Albert (28 March 2001). Medical Management of Radiation Accidents. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-7004-5. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- Trabalka, John R. (1979). "Russian Experience". Environmental Decontamination: Proceedings of the Workshop, 4–5 December 1979, Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. pp. 3–8. CONF-791234.

- Gyorgy, A. (1979). No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power. ISBN 978-0-919618-95-4.

- Newtan, Samuel Upton (2007). Nuclear War I and Other Major Nuclear Disasters of the 20th century. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781425985127.

- Smith, R. Jeffrey (10 July 1989). "Soviets Tell About Nuclear Plant Disaster; 1957 Reactor Mishap May Be Worst Ever". The Washington Post. p. A1. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Rabl, Thomas (2012). "The Nuclear Disaster of Kyshtym 1957 and the Politics of the Cold War". Environment and Society Portal. Arcadia: Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society (20).

External links

- Focus on the 60th anniversary of the Kyshtym Accident and the Windscale Fire

- An Analysis of the alleged Kyshtym Disaster

- Der nukleare Archipel (in German)

- Official documents pertaining to the disaster (in Russian)