| Long-tailed paradise whydah | |

|---|---|

_male.jpg.webp) | |

| Male, Chobe National Park, Botswana | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Viduidae |

| Genus: | Vidua |

| Species: | V. paradisaea |

| Binomial name | |

| Vidua paradisaea | |

| |

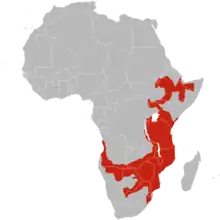

| resident range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Emberiza paradisaea Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The long-tailed paradise whydah or eastern paradise whydah (Vidua paradisaea) is from the family Viduidae of the order Passeriformes. They are small passerines with short, stubby bills found across Sub-Saharan Africa. They are mostly granivorous and feed on seeds that have ripen and fall on the ground. The ability to distinguish between males and females is quite difficult unless it is breeding season. During this time, the males molt into breeding plumage where they have one distinctive feature which is their long tail. It can grow up to three times longer than its own body or even more. Usually, the whydahs look like ordinary sparrows with short tails during the non-breeding season. In addition, hybridization can occur with these paradise whydahs. Males are able to mimic songs where females can use that to discover their mate. However, there are some cases where females don't use songs to choose their mate but they use either male characteristics like plumages or they can have a shortage of options with song mimicry. Paradise whydahs are brood parasites. They won't destroy the eggs that are originally there but will lay their own eggs in other songbirds nest. Overall, these whydahs are considered least concerned based on the IUCN Red List of threatened species.

Taxonomy and systematics

The long-tailed paradise whydah was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Emberiza paradisaea.[2] It is now placed in the genus Vidua that was introduced by the French naturalist Georges Cuvier in 1816.[3]

The long-tailed paradise whydahs are brood-parasitic birds along with the rest of the species in the family Viduidae. Primary host species include the Viduidae and the Estrildidae, also known as the waxbills. They diverged about 20 million years ago.[4] Most have included Viduidae within Estrilididae or Ploceidae (weavers) in a subfamily of its own.[5] Similarly, Anomalospiza have been switched around between the two families and have not been linked with Vidua.[5] However, studies has shown that the skull, the bony palate, the horny palate and the pterylosis are some of the morphological characters that support a close relationship between Anomalospiza and Vidua which are different from the weavers.[4] Indigobirds are also part of the family Viduidae. The long-tailed whydah's relationship with the indigobirds are not very well-known. The indigobirds are more closely related to the straw-tailed whydah based on their phylogenetic relationship where researchers analyzed mitochondrial restriction sites and nucleotide sequences.[4]

Description

Viduidae species differ from one another in size, in breeding plumage and color, and in the songs used for mating.[4] These long-tailed paradise whydahs are hard to distinguish between males and females. Usually these paradise whydah finches grow to about 13 centimeters in length and weigh about 21 grams.[4] Female whydahs tend to have a grey bill and feathers that are greyish-brown with blackish streaks along with their under tail feather being more white.[4] Similarly, males during the non-breeding season tend to have mostly browner plumage with black stripes on the crown, black parts along the face, and deeper brown color for the chest and creamer color for the abdomen[4] However, breeding males have black heads and back, the rusty colored breast, a bright yellow nape, and white abdomen with broad, elongated black tail feathers that can grow up to 36 centimeters or more.[4]

_(17329851342).jpg.webp) Male in breeding plumage

Male in breeding plumage Male going into breeding

Male going into breeding Female

Female

Distribution and habitat

The long-tailed paradise whydahs are found in grassland, savanna and open woodland where they live in bushed grassland around cultivation.[4] Majority of the time, these whydahs stay away from surface waters.[4]

Behavior and ecology

The long-tailed paradise whydah are known to be brood parasites where they would lay their eggs in nests of other songbirds.[4][6] Furthermore, they usually roost together in flocks during both breeding and non-breeding seasons.[4] Males develop the ability to mimic songs of their host.[7][8] Studies showed that female whydahs respond more strongly to songs mimicked by males of their own species than they do to closely related species.[9][10][11] Females use this mimicry to eliminate among potential mates and prefer those raised by the same host species.[8][12] Researchers discovered that hybridization can occur when female whydahs do not choose mates based on their song mimicry but instead on male traits such as plumage and flight displays if it is more important to them than song, or is restricted by the availability of males singing the appropriate host songs or if males is involved with unsolicited copulation with females of other parasitic species.[8][13][14] Researchers discovered that these paradise whydahs mimic the songs of Melba Finch.[8][7]

_and_Cut-throat_Finches_(Amadina_fasciata)_(6046350546).jpg.webp)

Additionally, these paradise whydahs are granivorous where they feed on small seed that ripen and fall on the ground.[4] For foraging, these finches use something called “double scratch” where they utilize both of their feet almost simultaneously scratching the ground to find seeds in dust and hop backwards to pick up the seed.[4] Another technique they use is their tongue. They would dehusks grass seeds with their bill rolling the seeds with their tongue one at a time back and forth against the ridge of the palate.[4]

Relationship to humans

Whydahs in general are known to be kept as cage birds for their song and colorful breeding plumage for many years.[4] In 1581, a renaissance scholar named Michel de Montaigne visited Florence where he was able to see these paradise whydahs in the Medici aviaries.[4] He described them with la cue deus longues plumes comme celles d’un chapon which in translation meant “a tail of two long plumes like those of a rooster”.[4] Ligozzi, a chief botanical painter of the Medici aviaries, illustrated a painting of the common fig where people later identified that the two birds in the painting were actually the paradise whydah and the indigobird.[4] Other than the beauty, the paradise whydahs can be a nuisance especially for farmers. For instance, in the highlands of Guinea and Sierra Leone, these paradise whydahs feed on small seeds of cultivated fonio which is known as “acha” or “hungry rice” before they can be harvested and that also happens to be the first food source available to the human inhabitants after the season of rains.[4]

Status

Widespread throughout its large range, the long-tailed paradise whydah is evaluated as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2018). "Vidua paradisaea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22720012A132135621. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22720012A132135621.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 178.

- ↑ Cuvier, Georges (1816). Le Règne animal distribué d'après son organisation : pour servir de base a l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction a l'anatomie comparée (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Déterville. pp. 388–389.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 John, Roy (2011-01-01). ""Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 15. Weavers to New World Warblers" edited by Josep del Hoyo et al. 2008. [book review]". The Canadian Field-Naturalist. 125 (1): 83. doi:10.22621/cfn.v125i1.1139. ISSN 0008-3550.

- 1 2 Chapin, James P. (October 1929). "Nomenclature and Systematic Position of the Paradise Whydahs". The Auk. 46 (4): 474–484. doi:10.2307/4076183. ISSN 0004-8038. JSTOR 4076183.

- ↑ Payne, Robert B.; Payne, Laura L.; Woods, Jean L.; Sorenson, Michael D. (January 2000). "Imprinting and the origin of parasite–host species associations in brood-parasitic indigobirds, Vidua chalybeata". Animal Behaviour. 59 (1): 69–81. doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1283. ISSN 0003-3472. PMID 10640368. S2CID 22363915.

- 1 2 PAYNE, ROBERT B; PAYNE, LAURA L; WOODS, JEAN L (June 1998). "Song learning in brood-parasitic indigobirdsVidua chalybeata: song mimicry of the host species". Animal Behaviour. 55 (6): 1537–1553. doi:10.1006/anbe.1997.0701. ISSN 0003-3472. PMID 9641999. S2CID 17693319.

- 1 2 3 4 Payne, Robert B.; Sorenson, Michael D. (2004). "Behavioral and Genetic Identification of a Hybrid Vidua: Maternal Origin and Mate Choice in a Brood-Parasitic Finch". The Auk. 121 (1): 156. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2004)121[0156:bagioa]2.0.co;2. ISSN 0004-8038.

- ↑ Payne, Robert B. (1980). Behavior and Songs of Hybrid Parasitic Finches. OCLC 869799441.

- ↑ Payne, Robert B. (January 1973). "Behavior, Mimetic Songs and Song Dialects, and Relationships of the Parasitic Indigobirds (Vidua) of Africa". Ornithological Monographs (11): ii–333. doi:10.2307/40166751. ISSN 0078-6594. JSTOR 40166751. S2CID 84118406.

- ↑ Payne, R.B. (November 1973). "Vocal mimicry of the paraside whydahs (Vidua) and response of female whydahs to the songs of their hosts (Pytilia) and their mimics". Animal Behaviour. 21 (4): 762–771. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(73)80102-2. ISSN 0003-3472.

- ↑ Oakes, Edward J.; Barnard, Phoebe (October 1994). "Fluctuating asymmetry and mate choice in paradise whydahs, Vidua paradisaea: an experimental manipulation". Animal Behaviour. 48 (4): 937–943. doi:10.1006/anbe.1994.1319. ISSN 0003-3472. S2CID 53195903.

- ↑ Grant, Peter R.; Grant, B. Rosemary (January 1997). "Hybridization, Sexual Imprinting, and Mate Choice". The American Naturalist. 149 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1086/285976. ISSN 0003-0147. S2CID 83665115.

- ↑ Barnard, Phoebe (April 1990). "Male tail length, sexual display intensity and female sexual response in a parasitic African finch". Animal Behaviour. 39 (4): 652–656. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(05)80376-8. ISSN 0003-3472. S2CID 54339389.