The ecliptic or ecliptic plane is the orbital plane of Earth around the Sun.[1][2][lower-alpha 1] From the perspective of an observer on Earth, the Sun's movement around the celestial sphere over the course of a year traces out a path along the ecliptic against the background of stars.[3] The ecliptic is an important reference plane and is the basis of the ecliptic coordinate system.

Sun's apparent motion

The ecliptic is the apparent path of the Sun throughout the course of a year.[4]

Because Earth takes one year to orbit the Sun, the apparent position of the Sun takes one year to make a complete circuit of the ecliptic. With slightly more than 365 days in one year, the Sun moves a little less than 1° eastward[5] every day. This small difference in the Sun's position against the stars causes any particular spot on Earth's surface to catch up with (and stand directly north or south of) the Sun about four minutes later each day than it would if Earth did not orbit; a day on Earth is therefore 24 hours long rather than the approximately 23-hour 56-minute sidereal day. Again, this is a simplification, based on a hypothetical Earth that orbits at uniform speed around the Sun. The actual speed with which Earth orbits the Sun varies slightly during the year, so the speed with which the Sun seems to move along the ecliptic also varies. For example, the Sun is north of the celestial equator for about 185 days of each year, and south of it for about 180 days.[6] The variation of orbital speed accounts for part of the equation of time.[7]

Because of the movement of Earth around the Earth–Moon center of mass, the apparent path of the Sun wobbles slightly, with a period of about one month. Because of further perturbations by the other planets of the Solar System, the Earth–Moon barycenter wobbles slightly around a mean position in a complex fashion.

Relationship to the celestial equator

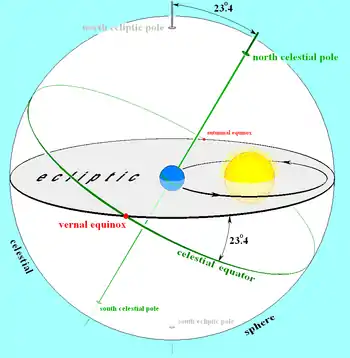

Because Earth's rotational axis is not perpendicular to its orbital plane, Earth's equatorial plane is not coplanar with the ecliptic plane, but is inclined to it by an angle of about 23.4°, which is known as the obliquity of the ecliptic.[8] If the equator is projected outward to the celestial sphere, forming the celestial equator, it crosses the ecliptic at two points known as the equinoxes. The Sun, in its apparent motion along the ecliptic, crosses the celestial equator at these points, one from south to north, the other from north to south.[5] The crossing from south to north is known as the vernal equinox, also known as the first point of Aries and the ascending node of the ecliptic on the celestial equator.[9] The crossing from north to south is the autumnal equinox or descending node.

The orientation of Earth's axis and equator are not fixed in space, but rotate about the poles of the ecliptic with a period of about 26,000 years, a process known as lunisolar precession, as it is due mostly to the gravitational effect of the Moon and Sun on Earth's equatorial bulge. Likewise, the ecliptic itself is not fixed. The gravitational perturbations of the other bodies of the Solar System cause a much smaller motion of the plane of Earth's orbit, and hence of the ecliptic, known as planetary precession. The combined action of these two motions is called general precession, and changes the position of the equinoxes by about 50 arc seconds (about 0.014°) per year.[10]

Once again, this is a simplification. Periodic motions of the Moon and apparent periodic motions of the Sun (actually of Earth in its orbit) cause short-term small-amplitude periodic oscillations of Earth's axis, and hence the celestial equator, known as nutation.[11] This adds a periodic component to the position of the equinoxes; the positions of the celestial equator and (vernal) equinox with fully updated precession and nutation are called the true equator and equinox; the positions without nutation are the mean equator and equinox.[12]

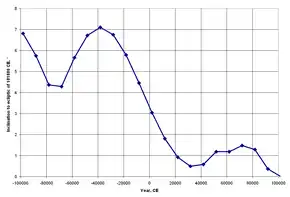

Obliquity of the ecliptic

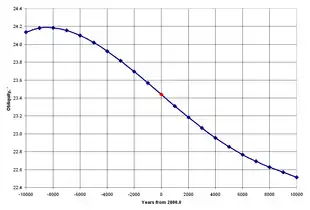

Obliquity of the ecliptic is the term used by astronomers for the inclination of Earth's equator with respect to the ecliptic, or of Earth's rotation axis to a perpendicular to the ecliptic. It is about 23.4° and is currently decreasing 0.013 degrees (47 arcseconds) per hundred years because of planetary perturbations.[13]

The angular value of the obliquity is found by observation of the motions of Earth and other planets over many years. Astronomers produce new fundamental ephemerides as the accuracy of observation improves and as the understanding of the dynamics increases, and from these ephemerides various astronomical values, including the obliquity, are derived.

Until 1983 the obliquity for any date was calculated from work of Newcomb, who analyzed positions of the planets until about 1895:

ε = 23°27′08.26″ − 46.845″ T − 0.0059″ T2 + 0.00181″ T3

where ε is the obliquity and T is tropical centuries from B1900.0 to the date in question.[15]

From 1984, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's DE series of computer-generated ephemerides took over as the fundamental ephemeris of the Astronomical Almanac. Obliquity based on DE200, which analyzed observations from 1911 to 1979, was calculated:

ε = 23°26′21.45″ − 46.815″ T − 0.0006″ T2 + 0.00181″ T3

where hereafter T is Julian centuries from J2000.0.[16]

JPL's fundamental ephemerides have been continually updated. The Astronomical Almanac for 2010 specifies:[17]

ε = 23°26′21.406″ − 46.836769″ T − 0.0001831″ T2 + 0.00200340″ T3 − 0.576×10−6″ T4 − 4.34×10−8″ T5

These expressions for the obliquity are intended for high precision over a relatively short time span, perhaps several centuries.[18] J. Laskar computed an expression to order T10 good to 0.04″/1000 years over 10,000 years.[14]

All of these expressions are for the mean obliquity, that is, without the nutation of the equator included. The true or instantaneous obliquity includes the nutation.[19]

Plane of the Solar System

|

|

|

| Top and side views of the plane of the ecliptic, showing planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. Most of the planets orbit the Sun very nearly in the same plane in which Earth orbits, the ecliptic. | Five planets (Earth included) lined up along the ecliptic in July 2010, illustrating how the planets orbit the Sun in nearly the same plane. Photo taken at sunset, looking west over Surakarta, Java, Indonesia. | |

Most of the major bodies of the Solar System orbit the Sun in nearly the same plane. This is likely due to the way in which the Solar System formed from a protoplanetary disk. Probably the closest current representation of the disk is known as the invariable plane of the Solar System. Earth's orbit, and hence, the ecliptic, is inclined a little more than 1° to the invariable plane, Jupiter's orbit is within a little more than ½° of it, and the other major planets are all within about 6°. Because of this, most Solar System bodies appear very close to the ecliptic in the sky.

The invariable plane is defined by the angular momentum of the entire Solar System, essentially the vector sum of all of the orbital and rotational angular momenta of all the bodies of the system; more than 60% of the total comes from the orbit of Jupiter.[20] That sum requires precise knowledge of every object in the system, making it a somewhat uncertain value. Because of the uncertainty regarding the exact location of the invariable plane, and because the ecliptic is well defined by the apparent motion of the Sun, the ecliptic is used as the reference plane of the Solar System both for precision and convenience. The only drawback of using the ecliptic instead of the invariable plane is that over geologic time scales, it will move against fixed reference points in the sky's distant background.[21][22]

Celestial reference plane

The ecliptic forms one of the two fundamental planes used as reference for positions on the celestial sphere, the other being the celestial equator. Perpendicular to the ecliptic are the ecliptic poles, the north ecliptic pole being the pole north of the equator. Of the two fundamental planes, the ecliptic is closer to unmoving against the background stars, its motion due to planetary precession being roughly 1/100 that of the celestial equator.[23]

Spherical coordinates, known as ecliptic longitude and latitude or celestial longitude and latitude, are used to specify positions of bodies on the celestial sphere with respect to the ecliptic. Longitude is measured positively eastward[5] 0° to 360° along the ecliptic from the vernal equinox, the same direction in which the Sun appears to move. Latitude is measured perpendicular to the ecliptic, to +90° northward or −90° southward to the poles of the ecliptic, the ecliptic itself being 0° latitude. For a complete spherical position, a distance parameter is also necessary. Different distance units are used for different objects. Within the Solar System, astronomical units are used, and for objects near Earth, Earth radii or kilometers are used. A corresponding right-handed rectangular coordinate system is also used occasionally; the x-axis is directed toward the vernal equinox, the y-axis 90° to the east, and the z-axis toward the north ecliptic pole; the astronomical unit is the unit of measure. Symbols for ecliptic coordinates are somewhat standardized; see the table.[24]

| Spherical | Rectangular | |||

| Longitude | Latitude | Distance | ||

| Geocentric | λ | β | Δ | |

| Heliocentric | l | b | r | x, y, z[note 1] |

| ||||

Ecliptic coordinates are convenient for specifying positions of Solar System objects, as most of the planets' orbits have small inclinations to the ecliptic, and therefore always appear relatively close to it on the sky. Because Earth's orbit, and hence the ecliptic, moves very little, it is a relatively fixed reference with respect to the stars.

Because of the precessional motion of the equinox, the ecliptic coordinates of objects on the celestial sphere are continuously changing. Specifying a position in ecliptic coordinates requires specifying a particular equinox, that is, the equinox of a particular date, known as an epoch; the coordinates are referred to the direction of the equinox at that date. For instance, the Astronomical Almanac[27] lists the heliocentric position of Mars at 0h Terrestrial Time, 4 January 2010 as: longitude 118°09′15.8″, latitude +1°43′16.7″, true heliocentric distance 1.6302454 AU, mean equinox and ecliptic of date. This specifies the mean equinox of 4 January 2010 0h TT as above, without the addition of nutation.

Eclipses

Because the orbit of the Moon is inclined only about 5.145° to the ecliptic and the Sun is always very near the ecliptic, eclipses always occur on or near it. Because of the inclination of the Moon's orbit, eclipses do not occur at every conjunction and opposition of the Sun and Moon, but only when the Moon is near an ascending or descending node at the same time it is at conjunction (new) or opposition (full). The ecliptic is so named because the ancients noted that eclipses only occur when the Moon is crossing it.[28]

Equinoxes and solstices

| ecliptic | equatorial | |

| longitude | right ascension | |

| March equinox | 0° | 0h |

| June solstice | 90° | 6h |

| September equinox | 180° | 12h |

| December solstice | 270° | 18h |

The exact instants of equinoxes and solstices are the times when the apparent ecliptic longitude (including the effects of aberration and nutation) of the Sun is 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°. Because of perturbations of Earth's orbit and anomalies of the calendar, the dates of these are not fixed.[29]

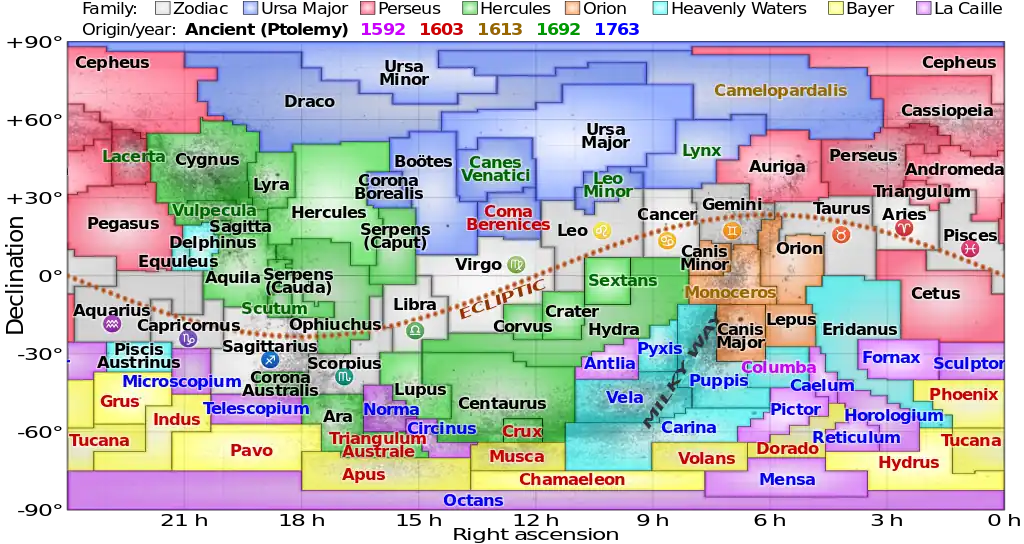

In the constellations

The ecliptic currently passes through the following constellations:

The constellations Cetus and Orion are not on the ecliptic, but are close enough that the Moon and planets can occasionally appear in them.[31]

Astrology

The ecliptic forms the center of the zodiac, a celestial belt about 20° wide in latitude through which the Sun, Moon, and planets always appear to move.[32] Traditionally, this region is divided into 12 signs of 30° longitude, each of which approximates the Sun's motion in one month.[33] In ancient times, the signs corresponded roughly to 12 of the constellations that straddle the ecliptic.[34] These signs are sometimes still used in modern terminology. The "First Point of Aries" was named when the March equinox Sun was actually in the constellation Aries; it has since moved into Pisces because of precession of the equinoxes.[35]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Strictly, the plane of the mean orbit, with minor variations averaged out.

- ↑ USNO Nautical Almanac Office; UK Hydrographic Office, HM Nautical Almanac Office (2008). The Astronomical Almanac for the Year 2010. GPO. p. M5. ISBN 978-0-7077-4082-9.

- ↑ "LEVEL 5 Lexicon and Glossary of Terms".

- ↑ "The Ecliptic: the Sun's Annual Path on the Celestial Sphere".

- ↑ U.S. Naval Observatory Nautical Almanac Office (1992). P. Kenneth Seidelmann (ed.). Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac. University Science Books, Mill Valley, CA. ISBN 0-935702-68-7., p. 11

- 1 2 3 The directions north and south on the celestial sphere are in the sense toward the north celestial pole and toward the south celestial pole. East is the direction toward which Earth rotates, west is opposite that.

- ↑ Astronomical Almanac 2010, sec. C

- ↑ Explanatory Supplement (1992), sec. 1.233

- ↑ Explanatory Supplement (1992), p. 733

- ↑ Astronomical Almanac 2010, p. M2 and M6

- ↑ Explanatory Supplement (1992), sec. 1.322 and 3.21

- ↑ U.S. Naval Observatory Nautical Almanac Office; H.M. Nautical Almanac Office (1961). Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Ephemeris and the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac. H.M. Stationery Office, London. , sec. 2C

- ↑ Explanatory Supplement (1992), p. 731 and 737

- ↑ Chauvenet, William (1906). A Manual of Spherical and Practical Astronomy. Vol. I. J.B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia., art. 365–367, p. 694–695, at Google books

- 1 2 Laskar, J. (1986). "Secular Terms of Classical Planetary Theories Using the Results of General Relativity". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 157 (1): 59. Bibcode:1986A&A...157...59L., table 8, at SAO/NASA ADS

- ↑ Explanatory Supplement (1961), sec. 2B

- ↑ U.S. Naval Observatory, Nautical Almanac Office; H.M. Nautical Almanac Office (1989). The Astronomical Almanac for the Year 1990. U.S. Govt. Printing Office. ISBN 0-11-886934-5., p. B18

- ↑ Astronomical Almanac 2010, p. B52

- ↑ Newcomb, Simon (1906). A Compendium of Spherical Astronomy. MacMillan Co., New York., p. 226-227, at Google books

- ↑ Meeus, Jean (1991). Astronomical Algorithms. Willmann-Bell, Inc., Richmond, VA. ISBN 0-943396-35-2., chap. 21

- ↑ "The Mean Plane (Invariable Plane) of the Solar System passing through the barycenter". 3 April 2009. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2009. produced with Vitagliano, Aldo. "Solex 10". Archived from the original (computer program) on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ↑ Danby, J.M.A. (1988). Fundamentals of Celestial Mechanics. Willmann-Bell, Inc., Richmond, VA. section 9.1. ISBN 0-943396-20-4.

- ↑ Roy, A.E. (1988). Orbital Motion (third ed.). Institute of Physics Publishing. section 5.3. ISBN 0-85274-229-0.

- ↑ Montenbruck, Oliver (1989). Practical Ephemeris Calculations. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-50704-3., sec 1.4

- ↑ Explanatory Supplement (1961), sec. 2A

- ↑ Explanatory Supplement (1961), sec. 1G

- ↑ Dziobek, Otto (1892). Mathematical Theories of Planetary Motions. Register Publishing Co., Ann Arbor, Michigan., p. 294, at Google books

- ↑ Astronomical Almanac 2010, p. E14

- ↑ Ball, Robert S. (1908). A Treatise on Spherical Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. p. 83.

- ↑ Meeus (1991), chap. 26

- ↑ Serviss, Garrett P. (1908). Astronomy With the Naked Eye. Harper & Brothers, New York and London. pp. 105, 106.

- ↑ Kidger, Mark (2005). Astronomical Enigmas: Life on Mars, the Star of Bethlehem, and Other Milky Way Mysteries. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9780801880261.

- ↑ Bryant, Walter W. (1907). A History of Astronomy. p. 3. ISBN 9781440057922.

- ↑ Bryant (1907), p. 4.

- ↑ See, for instance, Leo, Alan (1899). Astrology for All. L.N. Fowler & Company. p. 8.

astrology.

- ↑ Vallado, David A. (2001). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications (2nd ed.). El Segundo, CA: Microcosm Press. p. 153. ISBN 1-881883-12-4.

External links

- The Ecliptic: the Sun's Annual Path on the Celestial Sphere Durham University Department of Physics

- Seasons and Ecliptic Simulator University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- MEASURING THE SKY A Quick Guide to the Celestial Sphere James B. Kaler, University of Illinois

- Earth's Seasons Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Naval Observatory

- The Basics - the Ecliptic, the Equator, and Coordinate Systems AstrologyClub.Org

- Kinoshita, H.; Aoki, S. (1983). "The definition of the ecliptic". Celestial Mechanics. 31 (4): 329–338. Bibcode:1983CeMec..31..329K. doi:10.1007/BF01230290. S2CID 122913096.; comparison of the definitions of LeVerrier, Newcomb, and Standish.