| Part of a series on |

| Geography |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

Economic geography is the subfield of human geography that studies economic activity and factors affecting it. It can also be considered a subfield or method in economics.[1] There are four branches of economic geography.

Economic geography takes a variety of approaches to many different topics, including the location of industries, economies of agglomeration (also known as "linkages"), transportation, international trade, development, real estate, gentrification, ethnic economies, gendered economies, core-periphery theory, the economics of urban form, the relationship between the environment and the economy (tying into a long history of geographers studying culture-environment interaction), and globalization.

Theoretical background and influences

There are varied methodological approaches. Neoclassical location theorists, following in the tradition of Alfred Weber, tend to focus on industrial location and use quantitative methods. Since the 1970s, two broad reactions against neoclassical approaches have significantly changed the discipline: Marxist political economy, growing out of the work of David Harvey; and the new economic geography which takes into account social, cultural, and institutional factors in the spatial economy.

Economists such as Paul Krugman and Jeffrey Sachs have also analyzed many traits related to economic geography. Krugman called his application of spatial thinking to international trade theory the "new economic geography", which directly competes with an approach within the discipline of geography that is also called "new economic geography".[2] The name geographical economics has been suggested as an alternative.[3]

History

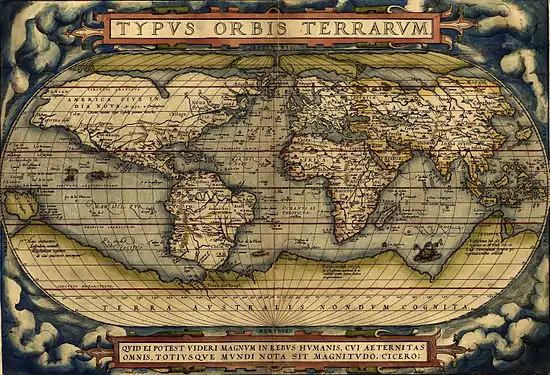

Early approaches to economic geography are found in the seven Chinese maps of the State of Qin, which date to the 4th century BC and in the Greek geographer Strabo's Geographika, compiled almost 2000 years ago. As cartography developed, geographers illuminated many aspects used today in the field; maps created by different European powers described the resources likely to be found in American, African, and Asian territories. The earliest travel journals included descriptions of the native people, the climate, the landscape, and the productivity of various locations. These early accounts encouraged the development of transcontinental trade patterns and ushered in the era of mercantilism.

Lindley M. Keasbey wrote in 1901 that no discipline of economic geography existed, with scholars either doing geography or economics.[4] Keasbey argued for a discipline of economic geography, writing,[4]

On the one hand, the economic activities of man are determined from the first by the phenomena of nature; and, on the other hand, the phenomena of nature are subsequently modified by the economic activities of man. Since this is the case, to start the deductions of economics, the inductions of geography are necessary; and to continue the inductions of geography, the deductions of economics are required. Logically, therefore, economics is impossible without geography, and geography is incomplete without economics.

World War II contributed to the popularization of geographical knowledge generally, and post-war economic recovery and development contributed to the growth of economic geography as a discipline. During environmental determinism's time of popularity, Ellsworth Huntington and his theory of climatic determinism, while later greatly criticized, notably influenced the field. Valuable contributions also came from location theorists such as Johann Heinrich von Thünen or Alfred Weber. Other influential theories include Walter Christaller's Central place theory, the theory of core and periphery.

Fred K. Schaefer's article "Exceptionalism in geography: A Methodological Examination", published in the American journal Annals of the Association of American Geographers, and his critique of regionalism, made a large impact on the field: the article became a rallying point for the younger generation of economic geographers who were intent on reinventing the discipline as a science, and quantitative methods began to prevail in research. Well-known economic geographers of this period include William Garrison, Brian Berry, Waldo Tobler, Peter Haggett and William Bunge.

Contemporary economic geographers tend to specialize in areas such as location theory and spatial analysis (with the help of geographic information systems), market research, geography of transportation, real estate price evaluation, regional and global development, planning, Internet geography, innovation, social networks.[5]

Approaches to study

As economic geography is a very broad discipline, with economic geographers using many different methodologies in the study of economic phenomena in the world some distinct approaches to study have evolved over time:

- Theoretical economic geography focuses on building theories about spatial arrangement and distribution of economic activities.

- Regional economic geography examines the economic conditions of particular regions or countries of the world. It deals with economic regionalization as well as local economic development.

- Historical economic geography examines the history and development of spatial economic structure. Using historical data, it examines how centers of population and economic activity shift, what patterns of regional specialization and localization evolve over time and what factors explain these changes.

- Evolutionary economic geography adopts an evolutionary approach to economic geography. More specifically, Evolutionary Economic Geography uses concepts and ideas from evolutionary economics to understand the evolution of cities, regions, and other economic systems.[6]

- Critical economic geography is an approach taken from the point of view of contemporary critical geography and its philosophy.

- Behavioral economic geography examines the cognitive processes underlying spatial reasoning, locational decision making, and behavior of firms[7] and individuals.

Economic geography is sometimes approached as a branch of anthropogeography that focuses on regional systems of human economic activity. An alternative description of different approaches to the study of human economic activity can be organized around spatiotemporal analysis, analysis of production/consumption of economic items, and analysis of economic flow. Spatiotemporal systems of analysis include economic activities of region, mixed social spaces, and development.

Alternatively, analysis may focus on production, exchange, distribution, and consumption of items of economic activity. Allowing parameters of space-time and item to vary, a geographer may also examine material flow, commodity flow, population flow and information flow from different parts of the economic activity system. Through analysis of flow and production, industrial areas, rural and urban residential areas, transportation site, commercial service facilities and finance and other economic centers are linked together in an economic activity system.

Branches

Thematically, economic geography can be divided into these subdisciplines:

It is traditionally considered the branch of economic geography that investigates those parts of the Earth's surface that are transformed by humans through primary sector activities. It thus focuses on structures of agricultural landscapes and asks for the processes that lead to these spatial patterns. While most research in this area concentrates rather on production than on consumption,[1] a distinction can be made between nomothetic (e.g. distribution of spatial agricultural patterns and processes) and idiographic research (e.g. human-environment interaction and the shaping of agricultural landscapes). The latter approach of agricultural geography is often applied within regional geography.

- Geography of industry

- Geography of international trade

- Geography of resources

- Geography of transport and communication

- Geography of finance

These areas of study may overlap with other geographical sciences.

Economists and economic geographers

Generally, spatially interested economists study the effects of space on the economy. Geographers, on the other hand, are interested in the economic processes' impact on spatial structures.

Moreover, economists and economic geographers differ in their methods in approaching spatial-economic problems in several ways. An economic geographer will often take a more holistic approach to the analysis of economic phenomena, which is to conceptualize a problem in terms of space, place, and scale as well as the overt economic problem that is being examined. The economist approach, according to some economic geographers, has the main drawback of homogenizing the economic world in ways economic geographers try to avoid.[8]

Variation by industry

Industries have different patterns of economic geography. Extractive industries tend to be concentrated around their specific natural resources. In Norway, for example, most oil industry jobs occur within a single electoral district. Industries are geographically concentrated if they do not need to be close to their end customers, such as the automotive industry concentration in Detroit, US. Agriculture also tends to be concentrated. Industries are geographically diffuse if they need to be close to their end customers, such as hairdressers, restaurants, and the hospitality industry.[9]

New economic geography

With the rise of the New Economy, economic inequalities are increasing spatially. The New Economy, generally characterized by globalization, increasing use of information and communications technology, the growth of knowledge goods, and feminization, has enabled economic geographers to study social and spatial divisions caused by the rising New Economy, including the emerging digital divide.

The new economic geographies consist of primarily service-based sectors of the economy that use innovative technology, such as industries where people rely on computers and the internet. Within these is a switch from manufacturing-based economies to the digital economy. In these sectors, competition makes technological changes robust. These high technology sectors rely heavily on interpersonal relationships and trust, as developing things like software is very different from other kinds of industrial manufacturing—it requires intense levels of cooperation between many different people, as well as the use of tacit knowledge. As a result of cooperation becoming a necessity, there is a clustering in the high-tech new economy of many firms.

Social and spatial divisions

As characterized through the work of Diane Perrons,[10] in Anglo-American literature, the New Economy consists of two distinct types. New Economic Geography 1 (NEG1) is characterized by sophisticated spatial modelling. It seeks to explain uneven development and the emergence of industrial clusters. It does so through the exploration of linkages between centripetal and centrifugal forces, especially those of economies of scale.

New Economic Geography 2 (NEG2) also seeks to explain the apparently paradoxical emergence of industrial clusters in a contemporary context, however, it emphasizes relational, social, and contextual aspects of economic behaviour, particularly the importance of tacit knowledge. The main difference between these two types is NEG2's emphasis on aspects of economic behaviour that NEG1 considers intangible.

Both New Economic Geographies acknowledge transport costs, the importance of knowledge in a new economy, possible effects of externalities, and endogenous processes that generate increases in productivity. The two also share a focus on the firm as the most important unit and on growth rather than development of regions. As a result, the actual impact of clusters on a region is given far less attention, relative to the focus on clustering of related activities in a region.

However, the focus on the firm as the main entity of significance hinders the discussion of New Economic Geography. It limits the discussion in a national and global context and confines it to a smaller scale context. It also places limits on the nature of the firm's activities and their position within the global value chain. Further work done by Bjorn Asheim (2001) and Gernot Grabher (2002) challenges the idea of the firm through action-research approaches and mapping organizational forms and their linkages. In short, the focus on the firm in new economic geographies is undertheorized in NEG1 and undercontextualized in NEG2, which limits the discussion of its impact on spatial economic development.

Spatial divisions within these arising New Economic geographies are apparent in the form of the digital divide, as a result of regions attracting talented workers instead of developing skills at a local level (see Creative Class for further reading). Despite increasing inter-connectivity through developing information communication technologies, the contemporary world is still defined through its widening social and spatial divisions, most of which are increasingly gendered. Danny Quah explains these spatial divisions through the characteristics of knowledge goods in the New Economy: goods defined by their infinite expansibility, weightlessness, and nonrivalry. Social divisions are expressed through new spatial segregation that illustrates spatial sorting by income, ethnicity, abilities, needs, and lifestyle preferences. Employment segregation is evidence by the overrepresentation of women and ethnic minorities in lower-paid service sector jobs. These divisions in the new economy are much more difficult to overcome as a result of few clear pathways of progression to higher-skilled work.

See also

- Business cluster

- Creative class

- Cultural geography

- Cultural geography

- Cultural economics

- Cultural psychology

- Environmental determinism

- Development geography

- Gravity model of trade

- Geography and wealth

- Location theory

- Land (economics)

- New Economy

- Regional science

- Retail geography

- Rural economics

- Spatial analysis

- Tobler's first law of geography

- Tobler's second law of geography

- Urban economics

- Weber problem

- Economic Geography (journal) - founded and published quarterly at Clark University since 1925

- Journal of Economic Geography - published by Oxford University Press since 2001[11]

References

- ↑ Clark, Gordon L.; Feldman, Maryann P.; Gertler, Meric S.; Williams, Kate (2003-07-10). The Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-925083-7.

- ↑ From S.N. Durlauf and L.E. Blume, ed. (2008). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition:

- "new economic geography" by Anthony J. Venables. Abstract.

- "regional development, geography of" by Jeffrey D. Sachs and Gordon McCord. Abstract.

- "gravity models" by Pierre-Philippe Combes. Abstract.

- "location theory" by Jacques-François Thisse. Abstract.

- "spatial economics" by Gilles Duranton. Abstract.

- "urban agglomeration" by William C. Strange. Abstract.

- "systems of cities" by J. Vernon Henderson. Abstract.

- "urban growth" by Yannis M. Ioannides and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg. Abstract.

- ↑ Steven Brakman; Harry Garretsen; Charles van Marrewijk. An Introduction to Geographical Economics.

- 1 2 Keasbey, Lindley M. (1901). "The Study of Economic Geography". Political Science Quarterly. 16 (1): 79–95. doi:10.2307/2140442. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2140442.

- ↑ Braha, Dan; Stacey, Blake; Bar-Yam, Yaneer (2011). "Corporate competition: A self-organized network" (PDF). Social Networks. 33 (3): 219–230. arXiv:1107.0539. Bibcode:2011arXiv1107.0539B. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2011.05.004. S2CID 1249348. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-13. Retrieved 2014-02-16.

- ↑ Boschma, Ron; Frenken, Koen (2006). "Why is economic geography not an evolutionary science? Towards an evolutionary economic geography". Journal of Economic Geography. 6 (3): 273–302. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbi022.

- ↑ Schoenberger, E (2001). "Corporate autobiographies: the narrative strategies of corporate strategists". Journal of Economic Geography. 1 (3): 277–98. doi:10.1093/jeg/1.3.277.

- ↑ Yeung, Henry W. C.; Kelly, Phillip (2007). Economic Geography: A Contemporary Introduction. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Rickard, Stephanie J. (2020). "Economic Geography, Politics, and Policy" (PDF). Annual Review of Political Science. 23: 187–202. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-033649.

- ↑ Perrons, Diane (2004). "Understanding Social and Spatial Divisions in the New Economy: New Media Clusters and the Digital Divide". Economic Geography. 80 (1): 45–61. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2004.tb00228.x. S2CID 144632958.

- ↑ Journal of Economic Geography

Further reading

- Barnes, T. J., Peck, J., Sheppard, E., and Adam Tickell (eds). (2003). Reading Economic Geography. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Combes, P. P., Mayer, T., Thisse, J.T. (2008). Economic Geography: The Integration of Regions and Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Description. Scroll down to chapter-preview links.

- Dicken, P. (2003). Global Shift: Reshaping the Global Economic Map in the 21st Century. New York: Guilford.

- Lee, R. and Wills, J. (1997). Geographies of Economies. London: Arnold.

- Massey, D. (1984). Spatial Divisions of Labour, Social Structures and the Structure of Production, MacMillan, London.

- Peck, J. (1996). Work-place: The Social Regulation of Labor Markets. New York: Guilford.

- Peck, J. (2001). Workfare States. New York: Guilford.

- Tóth, G., Kincses, Á., Nagy, Z. (2014). European Spatial Structure. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, ISBN 978-3-659-64559-4, doi:10.13140/2.1.1560.2247

External links

- Scientific journals

- Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie (TESG) - Published by The Royal Dutch Geographical Society (KNAG) since 1948.

- Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie - The German Journal of Economic Geography, published since 1956.

- Other