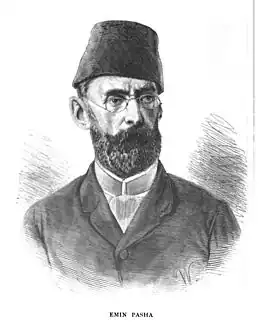

Mehmed Emin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Isaak Eduard Schnitzer March 28, 1840 |

| Died | October 23, 1892 (aged 52) Kinena Station, Nyangwe, Congo Free State |

| Awards | Vega Medal (1890) |

Mehmed Emin Pasha (born Isaak Eduard Schnitzer, baptized Eduard Carl Oscar Theodor Schnitzer; March 28, 1840 – October 23, 1892) was an Ottoman physician of German Jewish origin, naturalist, and governor of the Egyptian province of Equatoria on the upper Nile. The Ottoman Empire conferred the title "Pasha" on him in 1886, and thereafter he was referred to as "Emin Pasha".

Life and career

Emin was born in Oppeln (in present-day Poland), Silesia, into a middle-class German Jewish family, who moved to Neisse when he was two years old. After the death of his father in 1845, his mother married a Christian; she and her children were baptized Lutherans. He was a student at the Kolegium Carolinum Neisse in Nysa, Poland, at the universities at Breslau, Königsberg, and Berlin, qualifying as a physician in 1864. However, he was disqualified from practice, and left Germany for Constantinople, with the intention of entering Ottoman service.

Travelling via Vienna and Trieste, he stopped at Antivari in Montenegro, found himself welcomed by the local community, and was soon practicing medicine. He put his linguistic talent to good use, as well, adding Turkish, Albanian, and Greek to his repertoire of languages. He became the quarantine officer of the port, leaving only in 1870 to join the staff of Ismail Hakki Pasha, governor of northern Albania;[1] in the service, he travelled throughout the Ottoman Empire, although the details are little-known.

When Hakki Pasha died in 1873, Emin went back to Neisse with the pasha's widow and children, where he passed them off as his own family, but left suddenly in September 1875, reappearing in Cairo and then departing for Khartoum, where he arrived in December. At this point he took the name "Mehemet Emin" (Arabic Muhammad al-Amin), started a medical practice, and began collecting plants, animals, and birds, many of which he sent to museums in Europe. Although some regarded him as a Muslim, it is not clear if he ever actually converted.

Charles George Gordon (‘Gordon of Khartoum’), then governor of Equatoria, heard of Emin's presence and invited him to be the chief medical officer of the province; Emin assented and arrived there in May 1876. Gordon immediately sent Emin on diplomatic missions to Bunyoro and to Muteesa I of Buganda to the south, where Emin's modest style and fluency in Luganda were quite popular.

After 1876, Emin made Lado his base for collecting expeditions throughout the region. In 1878, the Khedive of Egypt appointed Emin as Gordon's successor to govern the province, giving him the title of Bey. Despite the grand title, there was little for Emin to do; his military force consisted of a few thousand soldiers who controlled no more than a mile's radius around each of their outposts, and the government in Khartoum was indifferent to his proposals for development. He showed himself to be a bitter foe of slavery.[2] In 1879 General Gordon gave Frank Lupton command of a flotilla of river steamers to relieve Emin. When Lupton reached Lado almost two years later he found that Emin did not want to be relieved. He became Emin's deputy, in charge of the Latuka district based at Tarangole.[3]

The revolt of Muhammad Ahmad that began in 1881 had cut Equatoria off from the outside world by 1883, and the following year, Karam Allah marched south to capture Equatoria and Emin. In 1885, Emin and most of his forces withdrew further south, to Wadelai near Lake Albert.[1] Cut off from communications to the north, he was still able to exchange mail with Zanzibar through Buganda. Determined to remain in Equatoria, his communiques, carried by his friend Wilhelm Junker, aroused considerable sentiment in Europe in 1886, particularly acute after the death of Gordon the previous year.

The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, led by Henry Morton Stanley, undertook to rescue Emin by going up the Congo River and then through the Ituri Forest, an extraordinarily difficult route that resulted in the loss of two-thirds of the expedition. Precise details of this trek are recorded in the published diaries of the expedition's non-African "officers" (e.g., Major Edmund Musgrave Barttelot, Captain William Grant Stairs, Mr. Arthur Jephson, and Thomas Heazle Parke, surgeon of the expedition). Stanley met Emin in April 1888, and after a year spent in argument and indecision, during which Emin and Jephson were imprisoned at Dufile by troops who mutinied from August to November 1888, Emin was convinced to leave for the coast. The bulk of his forces remained near Lake Albert until 1890, when Frederick Lugard took them with him to Kampala Hill, where they participated in the Battle of Kampala Hill. Stanley and Emin arrived in Bagamoyo in 1890. During celebrations, Emin was injured when he stepped through a window he mistook for an opening to a balcony. Emin spent two months in a hospital recovering, while Stanley left without being able to bring him back in triumph.[1]

The introduction of sleeping sickness in Uganda was attributed to the movement of Emin and his followers. Prior to the 1890s, sleeping sickness was unknown in Uganda, but the tsetse fly was probably brought by Emin from the Congo territory.[4]

Emin then entered the service of the German East Africa Company and accompanied Dr. Stuhlmann on an expedition to the lakes in the interior, but was killed by two Arab slave traders at Kinena Station in the Congo Free State,[2] near Nyangwe,[5] on 23 or 24 October 1892.[1]

Legacy

He added greatly to the anthropological knowledge of central Africa and published valuable geographical papers.[2] In 1890 he was awarded the Founder's Medal of the Royal Geographical Society.[6]

Emin Pasha is commemorated in the scientific name of an East African species of leptotyphlopid snake, Emin Pasha's worm snake Leptotyphlops emini,[7] and an East African species of Passer sparrow, the chestnut sparrow Passer eminibey.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 3 Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). . Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company.

- ↑ Macro, E. (1947), "Frank Miller Lupton", Sudan Notes and Records, University of Khartoum, 28: 50–61, JSTOR 41716507 – via JSTOR

- ↑ "50, 100 and 150 Years Ago", Scientific American, September 2010, page 12

- ↑ Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). . . Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

- ↑ "List of Past Gold Medal Winners" (PDF). Royal Geographical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Emin", p. 83).

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael (2003). Whose Bird? Men and Women Commemorated in the Common Names of Birds. London: Christopher Helm. 400 pp. ISBN 0-7136-6647-1. ("Emin Bey", p. 119).

External links

- Mohun, R. Dorsey (February 1895). "The Death of Emin Pasha". The Century. Congo Free State. Archived from the original on 2007-03-29. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Works by or about Emin Pasha at Internet Archive

- A.J. Mounteney Jephson, Diary, Edited by Dorothy Middleton, Hakluyt Society 1969

- Emin Pasha's family genealogy

- Newspaper clippings about Emin Pasha in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW