Sir Edward Henry | |

|---|---|

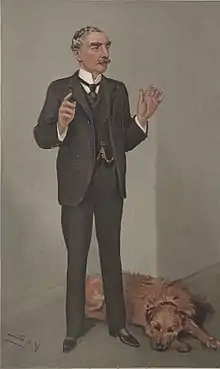

Edward Henry by Spy, 1905 | |

| Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis | |

| In office 1903 – 31 August 1918 | |

| Assistant Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (Crime) | |

| In office 1901–1903 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Edward Richard Henry 26 July 1850 Shadwell, London, England |

| Died | 19 February 1931 (aged 80) Cissbury, Ascot, Berkshire, England |

Sir Edward Richard Henry, 1st Baronet, GCVO, KCB, CSI, KPM (26 July 1850 – 19 February 1931) was the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (head of the Metropolitan Police of London) from 1903 to 1918. His time in the post saw the first discussions on the introduction of police dogs to the force, but he is best remembered today for his championship of the method of fingerprinting to identify criminals.

Early life

Henry was born in Shadwell, London to Irish parents;[1] his father was a doctor. He studied at St Edmund's College, Ware, Hertfordshire, and at sixteen he joined Lloyd's of London as a clerk. He meanwhile took evening classes at University College, London, to prepare for the entrance examination of the Indian Civil Service, which he then passed on 9 July 1873. As a result he was 'appointed by the (Her Majesty's) said [Principal] Secretary of State (Secretary of State for India) to be a member of the Civil Service at the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal' and on 28 July the same year he married Mary Lister at St Mary Abbots, the Parish Church of Kensington, London. Mary's father, Tom Lister, was the Estate Manager for the Earl of Stamford.

In September 1873 Edward Henry set sail for India. He arrived in Bombay and travelled across India arriving at Allahabad on 22 October 1873 to take up the position of Assistant Magistrate Collector within the Bengal Taxation Service. He became fluent in Urdu and Hindi. In 1888, he was promoted to Magistrate-Collector. In 1890, he became aide-de-camp and secretary to the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal and Joint Secretary to the Board of Revenue of Bengal. On 24 November 1890, as a widower, he remarried, by marrying Louisa Langrishe Moore.

Inspector-General of Police

On 2 April 1891, Henry was appointed Inspector-General of Police of Bengal. He had already been exchanging letters with Francis Galton regarding the use of fingerprinting to identify criminals, either instead of or in addition to the anthropometric method of Alphonse Bertillon, which Henry introduced into the Bengal police department.

The taking of fingerprints and palm prints had been common among officialdom in Bengal as a means of identification for forty years, having been introduced by Sir William Herschel, but it was not used by the police and there was no system of simple sorting to allow rapid identification of an individual print (although classification of types was already used).

Between July 1896 and February 1897, with the assistance of Sub-Inspectors Azizul Haque and Hemchandra Bose, Henry developed a system of fingerprint classification enabling fingerprint records to be organised and searched with relative ease. It was Haque who was primarily responsible for developing a mathematical formula to supplement Henry's idea of sorting in 1,024 pigeon holes based on fingerprint patterns. Years later, both Haque and Bose, on Henry's recommendation, received recognition by the British Government for their contribution to the development of fingerprint classification.[2][3][4]

In 1897, the Government of India published Henry's monograph, Classification and Uses of Fingerprints. The Henry Classification System quickly caught on with other police forces, and in July 1897 Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, the Governor-General of India, decreed that fingerprinting should be made an official policy of the British Raj. This classification system was developed to facilitate orderly storage and faster search of fingerprint cards, called ten print cards. It was used when the ten print cards were catalogued and searched manually and not digitally. Each ten print card was tagged with attributes that can vary from 1/1 to 32/32. In 1899, the use of fingerprint experts in court was recognised by the Indian Evidence Act.

In 1900, Henry was seconded to South Africa to organise the civil police in Pretoria and Johannesburg. In the same year, while on leave in London, Henry spoke before the Home Office Belper Committee on the identification of criminals on the merits of Bertillonage and fingerprinting.

Metropolitan Police

Assistant Commissioner (Crime)

In 1901, Henry was recalled to Britain to take up the office of Assistant Commissioner (Crime) at Scotland Yard, in charge of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). On 1 July 1901, Henry established the Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Bureau, Britain's first. Its primary purpose was originally not to assist in identifying criminals, but to prevent criminals from concealing previous convictions from the police, courts and prisons. However, it was used to ensure the conviction of burglar Harry Jackson in 1902 and soon caught on with CID. This usage was later cemented when fingerprint evidence was used to secure the convictions of Alfred and Albert Stratton for murder in 1905.

Henry introduced other innovations as well. He bought the first typewriters to be used in Scotland Yard outside the Registry, replacing the laborious hand copying of the clerks. In 1902, he ran a private telegraph line from Paddington Green Police Station to his home, and later replaced it with a telephone in 1904.

Appointment as Commissioner

On Sir Edward Bradford's retirement in 1903, Henry was appointed Commissioner, which had always been the Home Office's plan. Henry is generally regarded as one of the great Commissioners. He was responsible for dragging the Metropolitan Police into the modern day, and away from the class-ridden Victorian era. However, as Commissioner, he began to lose touch with his men, as others before him had done.

He continued with his technological innovations, installing telephones in all divisional stations and standardising the use of police boxes, which Bradford had introduced as an experiment but never expanded upon. He also soon increased the strength of the force by 1,600 men and introduced the first proper training for new constables.

Attempted assassination

On Wednesday 27 November 1912, while at his home in Kensington, Henry survived an assassination attempt by one Alfred (also reported as "Albert") Bowes, a disgruntled cab driver whose licence application had been refused. Bowes fired three shots with a revolver when Sir Edward opened his front door: two missed, and the third pierced Sir Edward's abdomen, missing all the vital organs. Sir Edward's chauffeur then tackled his assailant. Bowes faced a life sentence for attempted murder.

Sir Edward appeared at court and followed a humane tradition of pleading for leniency for his attacker, stating that Bowes had wanted to better himself and earn a living to improve the lot of his widowed mother. Bowes was sentenced to 15 years' penal servitude, but Sir Edward maintained an interest in his fate, and eventually paid for his passage to Canada for a fresh start when Bowes was released from prison in 1922. Sir Edward never really recovered from the ordeal, and the pain of the bullet wound recurred for the rest of his life.

Final years

Henry would have retired in 1914, but the outbreak of the First World War convinced him to remain in office, as his designated successor, General Sir Nevil Macready, was required by the War Office, where he was Adjutant-General. He remained in office throughout the war. His time as Commissioner finally ended due to the police strike of 1918. Police pay had not kept up with wartime inflation, and their conditions of service and pension arrangements were also poor. On 30 August 1918, 11,000 officers of the Metropolitan Police and City of London Police went on strike while Henry was on leave. The frightened government gave in to almost all their demands. Feeling let down both by his men and by the government, whom he saw as encouraging trade unionism within the police (something he vehemently disagreed with), Henry immediately resigned on 31 August. He was widely seen as a scapegoat for political failures.

Later life

In 1920 he and his family retired to Cissbury, near Ascot, Berkshire. He continued to be involved in fingerprinting advances and was on the committee of the Athenaeum Club and the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, as well as serving as a Justice of the Peace for Berkshire. His only son Edward John Grey Henry (he also had two daughters) died in 1930 aged 22 and Henry himself died at his home of a heart attack the following year, aged 80.

His grave lay unattended for many years. In April 1992, it was located in the cemetery adjoining All Souls Church, South Ascot by Metropolitan Police fingerprint expert Maurice Garvie & his wife Janis. After a presentation by Garvie to the Fingerprint Society on Henry's life and times, the Society agreed to the funding and restoration of the grave, a project completed in 1994. At Garvie's suggestion, a green plaque was unveiled on Sir Edward's retirement home 'Cissbury' by Berkshire County Council in 2000 and a blue plaque on his former London home, 19 Sheffield Terrace, Kensington, W.8 by English Heritage in 2001, the latter marking the centenary of the Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Bureau.

Honours

In 1898, he was made a Companion of the Star of India (CSI).[5] In 1905, Henry was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (CVO)[6] and the following year was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO).[7] In 1910 he was made Knight Commander of the Bath (KCB).[8]

In 1911, he was created a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO)[9] after attending the King and Queen at the Delhi Durbar. He was also a Grand Cross of the Dannebrog of Denmark, a Commander of the Légion d'honneur of France, and a member of the Order of Vila Viçosa of Portugal and the Order of St. Sava of Yugoslavia, as well as an Extra Equerry to the King. Henry was awarded the King's Police Medal (KPM) in the 1909 Birthday Honours.[10] On 25 November 1918, Henry was created a baronet,[11] though Edward John's death meant that that baronetcy went extinct on Edward's death.

Footnotes

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ↑ RK Tewari, KV Ravikumar (1 October 2000). ""History and development of forensic science in India", by R. K. Tewari and K. V. Ravikumar, Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 2000,46:303–308". Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. Jpgmonline.com. 46 (4): 303–308. PMID 11435664. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ "The forgotten Indian pioneers of fingerprint science", by J. S. Sodhi and Jasjeed Kaur, Current Science 2005, 88(1):185–191

- ↑ Beavan, Colin (2001). Fingerprints: The Origins of Crime Detection and Murder Case that Launched Forensic Science, by Colin Beavan, Hyperion, New York City, 2001. ISBN 0786885289.

- ↑ "No. 26969". The London Gazette (Supplement). 21 May 1898. p. 3230.

- ↑ "No. 27811". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 June 1905. p. 4550.

- ↑ "No. 27926". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 June 1906. p. 4462.

- ↑ "No. 28388". The London Gazette (Supplement to the London Gazette Extraordinary). 24 June 1910. p. 4476.

- ↑ "No. 28505". The London Gazette (Supplement). 19 June 1911. p. 4595.

- ↑ "No. 28306". The London Gazette. 9 November 1909. p. 8243.

- ↑ "No. 31032". The London Gazette. 26 November 1918. p. 13916.

References

- The Times Digital Archive

- Biography, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Martin Fido & Keith Skinner, The Official Encyclopedia of Scotland Yard (Virgin Books, London:1999)