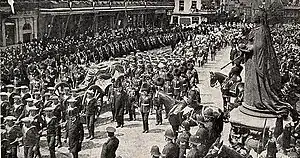

The funeral procession of King Edward VII, passing through Windsor | |

| Date |

|

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Participants | British royal family |

Edward VII, King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, died on Friday, 6 May 1910 at the age of 68. His state funeral occurred two weeks later, on 20 May 1910. He was succeeded by his eldest living son, George V.

The funeral was the largest gathering of European royalty ever to take place, and the last before many royal families were deposed in the First World War and its aftermath.[1]

Death

On 27 April 1910 the King returned to Buckingham Palace from France, suffering from severe bronchitis. Queen Alexandra returned from visiting her brother, George I of Greece, in Corfu a week later on 5 May.

On 6 May, Edward suffered several heart attacks, but refused to go to bed, saying, "No, I shall not give in; I shall go on; I shall work to the end."[2] Between moments of faintness, his son the Prince of Wales (shortly to be King George V) told him that his horse, Witch of the Air, had won at Kempton Park that afternoon. The King replied, "Yes, I have heard of it. I am very glad": his final words.[3] At 11:30 p.m. he lost consciousness for the last time and was put to bed. He died 15 minutes later.[2]

Alexandra refused to allow Edward's body to be moved for eight days afterwards, though she allowed small groups of visitors to enter his room.[4]

Lying-in-state

On 11 May, the King was dressed in his uniform and placed in a massive oak coffin, which was moved on 14 May to the throne room, where it was sealed and lay in state. Following that private lying in state,[5] on 17 May the coffin was taken in procession to Westminster Hall, where there was a public lying in state.[6] This was the first to be held in the hall for a member of the royal family and was inspired by the lying in state of William Gladstone there in 1898. A short service was held at the arrival of the coffin, with the combined choirs of Westminster Abbey and the Chapel Royal singing the hymn Praise, my soul, the King of heaven at the request of Queen Mary, although it was noted that their voices were drowned by the accompanying military band.[5]

.jpg.webp)

On the first day, thousands of members of the public queued patiently in the rain to pay their respects; some 25,000 people were turned away when the gates were closed at 10 pm. On 19 May, Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, wanted to have the hall closed while he laid a wreath; however, the police advised that there might be disorder if that happened, so the emperor was taken in through another entrance while the public continued to file past.[7] An estimated half a million people visited the hall during the three days that it was open.[8]

It was expected that theatres and the like would close, but King George issued a notice "to the effect that he wished things to go on as usual except on the actual day of the funeral, in view of the loss that would be inflicted on many persons ill able to bear it".[9]

State funeral

"So gorgeous was the spectacle on the May morning of 1910 when nine kings rode in the funeral of Edward VII of England that the crowd, waiting in hushed and black-clad awe, could not keep back gasps of admiration. In scarlet and blue and green and purple, three by three the sovereigns rode through the palace gates, with plumed helmets, gold braid, crimson sashes, and jeweled orders flashing in the sun. After them came five heirs apparent, forty more imperial or royal highnesses, seven queens—four dowager and three regnant—and a scattering of special ambassadors from uncrowned countries. Together they represented seventy nations in the greatest assemblage of royalty and rank ever gathered in one place and, of its kind, the last. The muffled tongue of Big Ben tolled nine by the clock as the cortege left the palace, but on history's clock it was sunset, and the sun of the old world was setting in a dying blaze of splendor never to be seen again."

The funeral was held two weeks after the King's death on 20 May. Huge crowds, estimated at between three and five million, gathered to watch the procession, the route of which was lined by 35,000 soldiers.[11] It passed from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Hall, where a small ceremony was conducted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson, before a small group of official mourners – the late King's widow Queen Alexandra, his son King George V, his daughter Princess Victoria, his brother the Duke of Connaught, and his nephew the German Emperor. The remainder of the funeral party waited outside the Hall, consisting of thousands of people. Big Ben, the bell in the nearby clock tower, was rung 68 times, one for each year of Edward VII's life. This was the first time it was used in this way at a monarch's funeral.[12]

The whole procession then proceeded from Westminster Hall, via Whitehall and the Mall, from Hyde Park Corner up to the Marble Arch, and thence to Paddington Station. Including other participants, 70 states were represented. The funeral procession saw a horseback procession, followed by 11 carriages. Caesar, the late King's dogs led the funeral procession with a highlander walking behind the carriage that carried the King's coffin. From Paddington Station, a funeral train conveyed the mourners to Windsor.[5] The mourners used the Royal Train, which together with the funeral car built for Queen Victoria, was hauled by the GWR 4000 Class locomotive King Edward.[13] From the station, the procession then continued on to Windsor Castle, and a full funeral ceremony was held in St George's Chapel.

The funeral service followed the format used for Queen Victoria, except that it included the interment within the chapel, whereas Victoria had been interred at Royal Mausoleum, Frogmore. The liturgy was closely based on the Order for The Burial of the Dead from the Book of Common Prayer. Queen Alexandra had specifically requested an anthem by Sir Arthur Sullivan, Brother, thou art gone before us, however Archbishop Davidson and other senior clerics thought that the piece lacked sufficient gravitas and Alexandra was persuaded to accept instead His Body Is Buried In Peace, the chorus from George Frideric Handel's Funeral Anthem For Queen Caroline.[5] Alexandra also requested two hymns that were sung by the congregation, My God, my Father, while I stray and Now the labourer's task is o'er; this was an innovation at royal state funerals.[14]

The funeral directors to the Royal Household appointed to assist during this occasion were the family business of William Banting of St James's Street, London. The Banting family also conducted the funerals of King George III in 1820, King George IV in 1830, the Duke of Gloucester in 1834, the Duke of Wellington in 1852, Prince Albert in 1861, Prince Leopold in 1884, and Queen Victoria in 1901. The royal undertaking warrant for the Banting family ended in 1928 with the retirement of William Westport Banting.[15]

Burial

Edward's body was temporarily interred in the Royal Vault at Windsor under the Albert Memorial Chapel.[16] On the instructions of Queen Alexandra in 1919, a monument in the South Aisle was designed and executed by Bertram Mackennal, featuring tomb effigies of the King and Queen in white marble mounted on a black and green marble sarcophagus, where both bodies were interred two years after the Queen Mother's death on 22 April 1927.[16] Their caskets had been placed in front of the altar in the Albert Memorial Chapel after Alexandra's death in November 1925.[16] The monument includes a depiction of Edward's favourite dog, Caesar, lying at his feet.[17]

Guests

As per report in London Gazette.[18]

British royal family

- Queen Alexandra, the late King's widow

- The King and Queen, the late King's son and daughter-in-law

- The Duke of Cornwall, the late King's grandson

- The Prince Albert, the late King's grandson

- The Princess Mary, the late King's granddaughter

- The Prince Henry, the late King's grandson

- The Princess Royal and the Duke of Fife, the late King's daughter and son-in-law

- Princess Alexandra, the late King's granddaughter

- Princess Maud, the late King's granddaughter

- The Princess Victoria, the late King's daughter

The Queen and King of Norway, the late King's daughter and son-in-law (also nephew)

The Queen and King of Norway, the late King's daughter and son-in-law (also nephew)

- The King and Queen, the late King's son and daughter-in-law

- Princess and Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, the late King's sister and brother-in-law

- Prince Albert of Schleswig-Holstein, the late King's nephew

- Princess Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, the late King's niece

- Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein, the late King's niece

- The Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll and the Duke of Argyll, the late King's sister and brother-in-law

- The Duke and Duchess of Connaught and Strathearn, the late King's brother and sister-in-law

- Prince Arthur of Connaught, the late King's nephew

- Princess Patricia of Connaught, the late King's niece

- Princess Henry of Battenberg, the late King's sister

- Prince Alexander of Battenberg, the late King's nephew

- Prince Maurice of Battenberg, the late King's nephew

- The Duchess of Albany, the late King's sister-in-law

.svg.png.webp) The Duke and Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Duke and Duchess of Albany), the late King's nephew and niece-in-law (also half-first cousin twice removed)

The Duke and Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Duke and Duchess of Albany), the late King's nephew and niece-in-law (also half-first cousin twice removed)

- Princess and Prince Louis of Battenberg, the late King's niece and nephew-in-law

- Princess Louise of Battenberg, the late King's great-niece

- Prince George of Battenberg, the late King's great-nephew

- Princess Victor of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, widow of the late King's half-first cousin

- Countess Feodora Gleichen, the late King's half-first cousin once removed

- Count Edward Gleichen, the late King's half-first cousin once removed

- The Duke and Duchess of Teck, the late King's second cousin and his wife

- Prince Francis of Teck, the late King's second cousin

- Prince Alexander of Teck, the late King's second cousin (also nephew-in-law)

Foreign royalty

.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp) The German Emperor, the late King's nephew

The German Emperor, the late King's nephew.svg.png.webp) Prince Henry of Prussia, the late King's nephew

Prince Henry of Prussia, the late King's nephew The Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, the late King's nephew

The Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, the late King's nephew.svg.png.webp) The King of Spain, the late King's nephew-in-law

The King of Spain, the late King's nephew-in-law The Crown Prince of Romania, the late King's nephew-in-law (representing the King of the Romanians)

The Crown Prince of Romania, the late King's nephew-in-law (representing the King of the Romanians) The King of Denmark, the late King's brother-in-law

The King of Denmark, the late King's brother-in-law The Duke of Västergötland, the late King's nephew-in-law (representing the King of Sweden)

The Duke of Västergötland, the late King's nephew-in-law (representing the King of Sweden).svg.png.webp) The King of the Hellenes, the late King's brother-in-law

The King of the Hellenes, the late King's brother-in-law

.svg.png.webp) The Duke of Sparta, the late King's nephew

The Duke of Sparta, the late King's nephew.svg.png.webp) Prince and Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark, the late King's nephew and great-niece

Prince and Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark, the late King's nephew and great-niece.svg.png.webp) Prince Christopher of Greece and Denmark, the late King's nephew

Prince Christopher of Greece and Denmark, the late King's nephew

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia, the late King's sister-in-law

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia, the late King's sister-in-law

Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia, the late King's nephew (representing the Russian Emperor)

Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia, the late King's nephew (representing the Russian Emperor)

- Prince George William of Hanover and Cumberland, the late King's nephew

.svg.png.webp) Prince Maximilian of Baden, the late King's nephew-in-law (representing the Grand Duke of Baden)

Prince Maximilian of Baden, the late King's nephew-in-law (representing the Grand Duke of Baden) The Tsar of the Bulgarians, the late King's second cousin

The Tsar of the Bulgarians, the late King's second cousin.svg.png.webp) The King of the Belgians, the late King's second cousin

The King of the Belgians, the late King's second cousin The Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the late King's second cousin

The Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the late King's second cousin

The Hereditary Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the late King's second cousin once removed

The Hereditary Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the late King's second cousin once removed The Crown Prince of Montenegro, husband of the late King's second cousin once removed (representing the Prince of Montenegro)

The Crown Prince of Montenegro, husband of the late King's second cousin once removed (representing the Prince of Montenegro)

.svg.png.webp) Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the late King's second cousin

Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the late King's second cousin

.svg.png.webp) Prince Leopold Clement of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the late King's second cousin once removed

Prince Leopold Clement of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the late King's second cousin once removed

- The Count of Eu, the late King's second cousin

- The Prince Imperial of Brazil, the late King's second cousin once removed

- The Duke of Alençon, the late King's second cousin

- The Duke of Vendôme, the late King's second cousin once removed

Duke Albrecht of Württemberg, the late King's second cousin once removed (representing the King of Württemberg)[19]

Duke Albrecht of Württemberg, the late King's second cousin once removed (representing the King of Württemberg)[19].svg.png.webp) The King of Portugal, the late King's second cousin twice removed

The King of Portugal, the late King's second cousin twice removed.svg.png.webp) The Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, brother of the late King's sister-in-law

The Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, brother of the late King's sister-in-law.svg.png.webp) Prince Wolrad of Waldeck and Pyrmont, half-brother of the late King's sister-in-law

Prince Wolrad of Waldeck and Pyrmont, half-brother of the late King's sister-in-law.svg.png.webp) Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria (representing the Emperor of Austria)

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria (representing the Emperor of Austria) The Crown Prince of the Ottoman Empire (representing the Ottoman Sultan)

The Crown Prince of the Ottoman Empire (representing the Ottoman Sultan)_crowned.svg.png.webp) The Duke of Aosta (representing the King of Italy)

The Duke of Aosta (representing the King of Italy).svg.png.webp) Prince Fushimi Sadanaru (representing the Emperor of Japan)

Prince Fushimi Sadanaru (representing the Emperor of Japan).svg.png.webp) Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria (representing the Prince Regent of Bavaria)

Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria (representing the Prince Regent of Bavaria).svg.png.webp) The Crown Prince of Serbia (representing the King of Serbia)

The Crown Prince of Serbia (representing the King of Serbia) Prince Henry of the Netherlands (representing the Queen of the Netherlands)

Prince Henry of the Netherlands (representing the Queen of the Netherlands).svg.png.webp) Prince Johann Georg of Saxony (representing the King of Saxony)

Prince Johann Georg of Saxony (representing the King of Saxony).svg.png.webp) Prince Mohammed Ali of Egypt (representing the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan)

Prince Mohammed Ali of Egypt (representing the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan).svg.png.webp) Prince Bovaradej of Siam (representing the King of Siam)

Prince Bovaradej of Siam (representing the King of Siam).svg.png.webp) Prince Zaitao of China (representing the Emperor of China)

Prince Zaitao of China (representing the Emperor of China) Grand Duke Michael Mikhailovich of Russia

Grand Duke Michael Mikhailovich of Russia- The Duke of Penthièvre

- The Landgrave of Hesse

- The Prince Kinsky of Wchinitz and Tettau

Other dignitaries

Former President Theodore Roosevelt, representing the United States

Former President Theodore Roosevelt, representing the United States.svg.png.webp) Foreign Affairs Minister Stephen Pichon, representing the French Republic

Foreign Affairs Minister Stephen Pichon, representing the French Republic.svg.png.webp) Samad Khan Momtaz os-Saltaneh, representing Persia

Samad Khan Momtaz os-Saltaneh, representing Persia- Sir George Reid, High Commissioner of Australia to the United Kingdom and former Prime Minister of Australia

- William Hall-Jones, High Commissioner of New Zealand to the United Kingdom and former Prime Minister of New Zealand

Nobility

- The Duke of Norfolk

- The Duke of Beaufort

- The Duke of Bedford

- The Duke of Montrose

- The Duke of Northumberland

- The Duke of Richmond and Gordon

- The Duchess of Buccleuch

- The Marquess of Cholmondeley

- The Marquess of Ripon

- The Marquess of Breadalbane

- The Marquess of Hertford

- The Marquess of Londonderry

- The Marquess of Salisbury

- The Earl of Granard

- The Earl Beauchamp

- The Earl of Dundonald

- The Earl Granville

- The Earl of Liverpool

- The Earl Howe

- The Earl of Gosford

- The Earl of Shaftesbury

- The Earl Roberts

- The Earl of Albemarle

- The Earl of Harrington

- The Earl of Stradbroke

- The Earl Fortescue

- The Earl of Scarbrough

- The Earl of Kilmorey

- The Earl Brownlow

- The Earl of Harewood

- The Earl of Clarendon

- The Earl of Haddington

- The Earl of Kintore

- The Earl of Leicester

- The Earl Cawdor

- The Earl of Rosebery

- The Earl of Denbigh

- The Viscount Althorp

- The Viscount Esher

- The Viscount Kitchener

- The Viscount Galway

- The Viscount Churchill

- The Lord Grenfell

- The Lord Acton

- The Lord Suffield

- The Lord Farquhar

- The Lord Colebrooke

- The Lord Herschell

- The Lord Allendale

- The Lord Denman

- The Lord Knollys

- The Lord Wenlock

- The Lord Lovat

- The Lord Harris

- The Lord Belper

- The Lord Fisher

- The Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal

- The Lord Hamilton of Dalzell

- The Lord Tweedmouth

- Lord Marcus Beresford

- Lord Charles Fitzmaurice

- Lord Walter Kerr

- Lord Algernon Percy

- The Hon. Seymour Fortescue

- The Hon. Henry Legge

- The Hon. Edmund Fremantle

- The Hon. Arthur Walsh

- The Hon. Sir Hedworth Lambton

- The Hon. Derek Keppel

- The Hon. Charles Wentworth-FitzWilliam

- The Hon. Sir Assheton Curzon-Howe

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Tuchman 2014, p. 1.

- 1 2 Bentley-Cranch, p. 151

- ↑ Matthew, H. C. G. (September 2004; online edition May 2006) "Edward VII (1841–1910)" Archived 2 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32975, retrieved 24 June 2009 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ Ridley, p. 558

- 1 2 3 4 Range, Matthias (2016). British Royal and State Funerals: Music and Ceremonial since Elizabeth I. Boydell Press. pp. 277–278. ISBN 978-1783270927.

- ↑ "Plaque: Westminster Hall - Edward VII". www.londonremembers.com. London Remembers. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ↑ Hibbert, Christopher (2007). Edward VII: The Last Victorian King. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 318. ISBN 978-1-4039-8377-0.

- ↑ Quigley, Christine (2005). The Corpse: A History. Jefferson NC: McFarland & Co. p. 67. ISBN 978-0786424498.

- ↑ "Our London Letter, 16 May 1910". Musical Canada. 5 (1): 43. May 1910.

- ↑ Tuchman, Barbara W. (1962). "A Funeral". The Guns of August. Penguin Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-2419-6822-2.

- ↑ Hopkins, John Castell (1910). The Life of King Edward VII. Palala Press (2016 reprint). p. 342. ISBN 978-1356057740.

- ↑ Weinreb & Hibbert 1992, p. 66

- ↑ Maggs, Colin (2011). The Branch Lines of Berkshire. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-1848683471.

- ↑ Range 2016, p. 281

- ↑ Todd Van Beck, "The Death and State Funeral of Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill", part II, in Canadian Funeral News (October 2012), Vol. 40 Issue 10, p. 10 (online Archived 2014-03-16 at the Wayback Machine)

- 1 2 3 Rainbird, Stephen Geoffrey (October 2015). "Expatriatism: A New Platform for Shaping Australian Artistic Practice in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries – A Case Study of Six Artists Working in Paris and London" (PDF). University of Tasmania. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ↑ Dodson, Aidan (2004). The Royal Tombs of Great Britain: An Illustrated History. Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd. p. 145. ISBN 978-0715633106.

- ↑ "No. 28401". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 July 1910.

- ↑ Tuchman 2014, p. 6.

Sources

- Bentley-Cranch, Dana (1992). Edward VII: Image of an Era 1841–1910. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-290508-0.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (2014). The Guns of August. Random House Trade. ISBN 978-0-345-38623-6.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher (1992). The London Encyclopaedia (reprint ed.). Macmillan.

- The Times, May 21, 1910

![]() Media related to Funeral of Edward VII of the United Kingdom at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Funeral of Edward VII of the United Kingdom at Wikimedia Commons