An eggshell is the outer covering of a hard-shelled egg and of some forms of eggs with soft outer coats.

Worm eggs

Nematode eggs present a two layered structure: an external vitellin layer made of chitin that confers mechanical resistance and an internal lipid-rich layer that makes the egg chamber impermeable.[1]

Insect eggs

Insects and other arthropods lay a large variety of styles and shapes of eggs. Some of them have gelatinous or skin-like coverings, others have hard eggshells. Softer shells are mostly protein. It may be fibrous or quite liquid. Some arthropod eggs do not actually have shells, rather, their outer covering is actually the outermost embryonic membrane, the choroid, which protects inner layers. This can be a complex structure, and it may have different layers, including an outermost layer called an exochorion. Eggs which must survive in dry conditions usually have hard eggshells, made mostly of dehydrated or mineralized proteins with pore systems to allow respiration. Arthropod eggs can have extensive ornamentation on their outer surfaces.

Fish, amphibian and reptile eggs

Fish and amphibians generally lay eggs which are surrounded by the extraembryonic membranes but do not develop a shell, hard or soft, around these membranes. Some fish and amphibian eggs have thick, leathery coats, especially if they must withstand physical force or desiccation. These types of eggs can also be very small and fragile.

While many reptiles lay eggs with flexible, calcified eggshells, there are some that lay hard eggs. Eggs laid by snakes generally have leathery shells which often adhere to one another. Depending on the species, turtles and tortoises lay hard or soft eggs. Several species lay eggs which are nearly indistinguishable from bird eggs.

Bird eggs

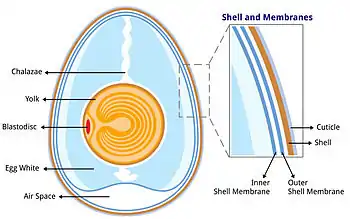

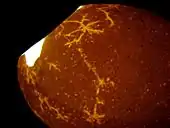

The bird egg is a fertilized gamete (or, in the case of some birds, such as chickens, possibly unfertilized) located on the yolk surface and surrounded by albumen, or egg white. The albumen in turn is surrounded by two shell membranes (inner and outer membranes) and then the eggshell. The chicken eggshell is 95-97%[2] calcium carbonate crystals, which are stabilized by a protein matrix.[3][4][2] Without the protein, the crystal structure would be too brittle to keep its form and the organic matrix is thought to have a role in deposition of calcium during the mineralization process.[5][6][7] The structure and composition of the avian eggshell protects the egg from damage and microbial contamination, prevents desiccation, regulates embryonic gas and water exchange and provides calcium for embryogenesis. Eggshell formation requires gram amounts of calcium being deposited within hours, which must be supplied via the hen's diet.[2]

The fibrous chicken shell membranes are added in the proximal (white) isthmus of the oviduct.[2] In the distal (red) isthmus mammillae or mammillary knobs are deposited on the surface of the outer membrane in a regular array pattern.[8][9] The mammillae are proteoglycan-rich and are thought to control calcification. In the shell gland (similar to a mammalian uterus), mineralization starts at the mammillae and around the outermost membrane fibers.[10] The shell gland fluid contains very high levels of calcium and bicarbonate ions. The thick calcified layer of the eggshell forms in columns from the mammillae structures, and is known as the palisade layer. Between these palisade columns are narrow pores that traverse the eggshell and allow gaseous exchange. The cuticle forms the final, outer layer of the eggshell.[11] Attachment of the soft organic fibrous membrane to the hard calcite shell is essential for proper chick embryonic development and growth (via ensuring association of the chorioallantoic membrane, and in allowing for air-sac formation at the blunt end of the egg). This attachment between dissimilar materials is facilitated by a structural interdigitation of fibers into each mammillae at the microscale, and reciprocally, at the nanoscale, mineral spiking into fibers directly at the interface [10]

While the bulk of eggshell is made of calcium carbonate, it is now thought that the protein matrix has an important role to play in eggshell strength.[12] These proteins affect crystallization, which in turn affects the eggshell structure. The concentration of eggshell proteins decreases over the life of the laying hen, as does eggshell strength.

In an average laying hen, the process of shell formation takes around 20 hours. Pigmentation is added to the shell by papillae lining the oviduct, coloring it any of a variety of colors and patterns depending on species. Since eggs are usually laid blunt end first, that end is subjected to most pressure during its passage and consequently shows the most color.

As they contain mainly calcium carbonate, bird eggshells dissolve in various acids, including the vinegar used in cooking. While dissolving, the calcium carbonate in an eggshell reacts with the acid to form carbon dioxide.[13]

Environmental issues

The US food industry generates 150,000 tons of shell waste per year.[14] The disposal methods for waste eggshells are 26.6% as fertilizer, 21.1% as animal feed ingredients, 26.3% discarded in municipal dumps, and 15.8% used in other ways.[15] Many landfills are unwilling to take the waste because the shells and the attached membrane attract vermin. When unseparated, the calcium carbonate eggshell and protein-rich membrane are useless.[16] Recent inventions have allowed for the egg cracking industry to separate the eggshell from the eggshell membrane. The eggshell is mostly made up of calcium carbonate and the membrane is valuable protein. When separated both products have an array of uses.

Mammal eggs

Monotremes, egg-laying mammals, lay soft-shelled eggs similar to those of reptiles. The shell is deposited on the egg in layers within the uterus. The egg can take up fluids and grow in size during this process, and the final, most rigid layer is not added until the egg is full-size.

Egg teeth

Hatching birds, amphibian and egg-laying reptiles have an egg-tooth used to start an exit hole in the hard eggshell.[17][18]

Uses

Eggshell waste is fundamentally composed of calcium carbonate, and has the potential to be used as raw material in the production of lime.[19]

Pharmaceuticals

The rich calcium carbonate shell has been used in the application for calcium deficiency therapies in humans and animals.[15][20] A single eggshell has a mass of six grams which yields around 2200 mg of calcium (6000 mg × 0.95 × 0.4= 2280 mg). Eggshell particles are used in toothpaste as an anti-tartar agent.[15] Powdered eggshells have been used for bone mineralization and growth.[15][21][20]

Food

Recent applications of eggshells include producing calcium lactate as a firming agent, a flavor enhancer, a leavening agent, a nutrient supplement, a stabilizer, and thickener.[15][20] Eggshells are also used as a calcium supplement in orange juice.[14]

Other

Eggshells have been incorporated into fertilizers as a soil conditioner.[15][22] They have also been used as a supplement to animal feed.[15][22] More recently the egg calcium carbonate particles have been used as coating pigments for ink-jet printing.[22] Powdered eggshells are also used in making paper pulp.[14] Recently eggshell waste has been used as a low cost catalyst for biodiesel production.[21] Chicken eggshells have been additionally incorporated as a calcium precursor into the synthesis of calcium-based metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).[23]

Recently, researchers have utilized chicken eggshells as a biofiller with a conducting polymer to enhance its sensing properties. Typically, eggshells were used as biofiller in polyaniline matrix to detect ammonia gas. The optimum ratio between eggshells and polyaniline could enhance this sensor measurement.[24]

Ostrich eggshells have been used by Sub Saharan hunter-gathers. For instance the Juǀʼhoansi have used them to carry water[25] and create beads from them.[26]

See also

- Eggshell skull rule, in tort law

- Walk on eggshells, an idiom in the English language

- Eggshell membrane, a dietary supplement

References

- ↑ Benenati G, Penkov S, Müller-Reichert T, Entchev EV, Kurzchalia TV (May–Jun 2009). "Two cytochrome P450s in Caenorhabditis elegans are essential for the organization of eggshell, correct execution of meiosis and the polarization of embryo". Mech Dev. 126 (5–6): 382–93. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2009.02.001. PMID 19368796.

- 1 2 3 4 Hunton, P (2005). "Research on eggshell structure and quality: an historical overview". Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola. 7 (2): 67–71. doi:10.1590/S1516-635X2005000200001.

- ↑ Arias, J. L.; Fernandez, M. S. (2001). "Role of extracellular matrix molecules in shell formation and structure". World's Poultry Science Journal. 57 (4): 349–357. doi:10.1079/WPS20010024. hdl:10533/197482. S2CID 86152776.

- ↑ Nys, Yves; Gautron, Joël; Garcia-Ruiz, Juan M.; Hincke, Maxwell T. (2004). "Avian eggshell mineralization: biochemical and functional characterization of matrix proteins". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 3 (6–7): 549–62. Bibcode:2004CRPal...3..549N. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2004.08.002.

- ↑ Romanoff, A.L., A.J. Romanoff (1949) The avian egg. New York, Wiley.

- ↑ Burley, R.W., D.V. Vadehra (1989) The Avian Egg: Chemistry and Biology. New York, Wiley.

- ↑ Lavelin, I; Meiri, N; Pines, M (2000). "New insight in eggshell formation". Poultry Science. 79 (7): 1014–7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.335.6360. doi:10.1093/ps/79.7.1014. PMID 10901204.

- ↑ Wyburn, GM; Johnston, HS; Draper, MH; Davidson, MF (1973). "The ultrastructure of the shell forming region of the oviduct and the development of the shell of Gallus domesticus". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology and Cognate Medical Sciences. 58 (2): 143–51. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.1973.sp002199. PMID 4487964. S2CID 40474330.

- ↑ Fernandez, MS; Araya, M; Arias, JL (1997). "Eggshells are shaped by a precise spatio-temporal arrangement of sequentially deposited macromolecules". Matrix Biology. 16 (1): 13–20. doi:10.1016/s0945-053x(97)90112-8. PMID 9181550.

- 1 2 Buss, Daniel J.; Reznikov, Natalie; McKee, Marc D. (December 2023). "Attaching organic fibers to mineral: The case of the avian eggshell". iScience. 26 (12): 108425. Bibcode:2023iSci...26j8425B. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.108425. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 10687338. PMID 38034363.

- ↑ "The Egg-Shell Microstructure Studied by Powder Diffraction". Xray.cz. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ↑ http://ict.udg.co.cu/FTPDocumentos/Literatura%20Cientifica/Maestria%20Nutricion%20Animal/6.%20EVENTOS%20RELEVANTES/XVII%20Congreso%20Avicultura/confs/hunton1.htm. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Q & A: Eggshells in Vinegar - What happened? | Department of Physics | University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign". Van.physics.illinois.edu. 2007-10-22. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- 1 2 3 Hecht J: Eggshells break into collagen market. New Scientist 1999, 161:6-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Daengprok W, Garnjanagoonchorn W, Mine Y: Fermented pork sausage fortified with commercial or hen eggshell calcium lactate. Meat Science 2002, 62:199-204.

- ↑ Wei Z; Li B; Xu C (2009). "Application of waste eggshell as low-cost solid catalyst for biodiesel production". Bioresource Technology. 100 (11): 2883–2885. Bibcode:2009BiTec.100.2883W. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2008.12.039. PMID 19201602.

- ↑ "What is Egg Shell Quality and How to Preserve It". Ag.ansc.purdue.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-12-08. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ↑ Nys, Yves; Gautron, Joël; Garcia-Ruiz, Juan M.; Hincke, Maxwell T. (2004). "Avian eggshell mineralization: biochemical and functional characterization of matrix proteins" (PDF). Comptes Rendus Palevol. 3 (6–7): 549–562. Bibcode:2004CRPal...3..549N. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2004.08.002.

- ↑ Ferraz, Eduardo; Gamelas, José A. F.; Coroado, João; Monteiro, Carlos; Rocha, Fernando (2018-09-03). "Eggshell waste to produce building lime: calcium oxide reactivity, industrial, environmental and economic implications". Materials and Structures. 51 (5). doi:10.1617/s11527-018-1243-7. ISSN 1359-5997. S2CID 139375677.

- 1 2 3 Daengprok W, Issigonis K, Mine Y, Pornsinpatip P, Garnjanagoonchorn W, Naivikul O: Chicken eggshell matrix proteins enhance calcium transport in the human intestinal epithelial cells, Caco-Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2003, 51:6056-6061.

- 1 2 Wei Z, Li B, Xu C: Application of waste eggshell as low-cost solid catalyst for biodiesel production [electronic resource]. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100:2883-2885.

- 1 2 3 Yoo S, Kokoszka J, Zou P, Hsieh JS: Utilization of calcium carbonate particles from eggshell waste as coating pigments for ink-jet printing paper [electronic resource]. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100:6416-6421.

- ↑ Crickmore, Tom S.; Sana, Haamidah Begum; Mitchell, Hannah; Clark, Molly; Bradshaw, Darren (2021-10-12). "Toward sustainable syntheses of Ca-based MOFs". Chemical Communications. 57 (81): 10592–10595. doi:10.1039/D1CC04032D. ISSN 1364-548X. PMID 34559869. S2CID 237628392.

- ↑ N A Mazlan, J M Sapari, K P Sambasevam, Synthesis and fabrication of polyaniline/eggshell composite in ammonia detection, Journal of Metals, Materials and Minerals, Vol 30, No. 2, 50-57 (2020).https://ojs.materialsconnex.com/index.php/jmmm/article/view/649

- ↑ Cummings, Vicky (2020). The Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers Key Themes for Archaeologists. Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ Stewart, Brian A.; Zhao, Yuchao; Mitchell, Peter J.; Dewar, Genevieve; Gleason, James D.; Blum, Joel D. (2020). "Ostrich eggshell bead strontium isotopes reveal persistent macroscale social networking across late Quaternary southern Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (12): 6453–6462. Bibcode:2020PNAS..117.6453S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1921037117. PMC 7104358. PMID 32152113.

Further reading

- Kilner, R. M. (2006). "The evolution of egg colour and patterning in birds". Biological Reviews. 81 (3): 383–406. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.565.8957. doi:10.1017/S1464793106007044. PMID 16740199. S2CID 21083885.