| Einiosaurus Temporal range: Upper Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skull, Los Angeles Natural History Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ceratopsia |

| Family: | †Ceratopsidae |

| Subfamily: | †Centrosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Pachyrhinosaurini |

| Genus: | †Einiosaurus Sampson, 1994 |

| Species: | †E. procurvicornis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Einiosaurus procurvicornis Sampson, 1994 | |

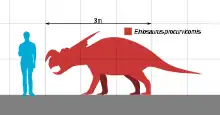

Einiosaurus is a genus of herbivorous centrosaurine ceratopsian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian stage) of northwestern Montana. The name means 'bison lizard', in a combination of Blackfeet Indian eini and Latinized Ancient Greek sauros; the specific name (procurvicornis) means 'with a forward-curving horn' in Latin. Einiosaurus is medium-sized with an estimated body length at 4.5 metres (15 ft).

History of discovery

The Landslide Butte expeditions

Einiosaurus is an exclusively Montanan dinosaur, and all of its known remains are currently held at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana. At least fifteen individuals of varying ages are represented by three adult skulls and hundreds of other bones from two low-diversity, monospecific (one species) bonebeds, which were discovered by Jack Horner in 1985 and excavated from 1985 to 1989 by Museum of the Rockies field crews.

Horner had not been searching for horned dinosaurs. In the spring of 1985 he had been informed by landowner Jim Peebles that he would no longer be allowed access to the Willow Creek "Egg Mountain" site where during six years a nesting colony of Maiasaura had been excavated.[1] This forced Horner to find an alternative site because supplies had already been bought for a new summer season and fourteen volunteers and students expected to be employed by him.[1] He investigated two sites, Devil's Pocket and Red Rocks, that however proved to contain too few fossils.[2] For some years, since 1982, Horner had requested from the Blackfeet Indian Tribal Council access to the Landslide Butte site. The field notes of Charles Whitney Gilmore from the 1920s indicated that dinosaur eggs could be found there. The council had consistently turned down his requests because they feared widespread disturbance of the reservation. However, one of its members, Marvin Weatherwax, had earlier in 1985 observed that an excavation by Horner of a mosasaurid in the Four Horns Lake had caused only limited damage to the landscape. In early July, the council granted Horner access to the entire reservation.[3]

Early in August, Horner's associate Bob Makela discovered the Dino Ridge Quarry, containing extensive ceratopsid remains, on the land of farmer Ricky Reagan.[4] Continual rainfall hampered operations that year.[5] On 20 June 1986, a crew of sixteen returned to reopen the quarry.[5] A large and dense concentration of bones, a bonebed, was excavated, with up to forty bones per square metre being present. This was interpreted as representing an entire herd that had perished.[6] In late August 1986, Horner and preparator Carrie Ancell on the land of Gloria Sundquist discovered a second horned dinosaur site, at one mile distance from the first, called the Canyon Bone Bed, in which two relatively complete skulls were dug up.[7] The skulls had to be removed from a rather steep cliff and weighed about half a tonne when plastered. They were airlifted by a Bell UH-1 Iroquois of the United States Army National Guard into trucks to be transported.[8] The aberrant build of these skulls first suggested to Horner that they might represent an unknown taxon.[9] Unexpectedly benefiting from a grant of $204,000 by the MacArthur Fellows Program,[10] Horner was able to reopen the two bonebed quarries in 1987.[11] That year almost all fossils were removed that could be accessed without using mechanised earth-moving equipment.[12] Also, an additional horned dinosaur skull was excavated from a somewhat younger layer.[13] In 1988, more ceratopsid material was found in a more southern site, the Blacktail Creek North.[14] In the second week of June 1989, student Scott Donald Sampson in the context of his doctoral research with a small crew reopened the Canyon Bone Bed, while Patrick Leiggi that summer with a limited number of workers restarted excavating the Dino Ridge Quarry.[15] The same year, Horner himself found more horned dinosaur fossils at the Blacktail Creek North.[16] In 1990, the expeditions were ended because the reservation allowed access to commercial fossil hunters who quickly strip-mined sites with bulldozers, through a lack of proper documentation greatly diminishing the scientific value of the discoveries.[17]

Identification problems

At the time of the expeditions, it was assumed that all horned dinosaur fossils found in the reservation belonged to a single species, especially as they came from a limited geological time period, its duration estimated at about half a million years.[18] In the 1920s, George Freyer Sternberg had already found ceratopsid bones there, that were named as a second species of Styracosaurus: Styracosaurus ovatus.[18] The material had been rather limited and the validity of this species had been doubted, some considering it a nomen dubium.[19] The abundant new remains seemed to prove that the species was real, also because it clearly differed from the type species of Styracosaurus, Styracosaurus albertensis.[18] The comprehensive taphonomic study by Raymond Robert Rogers from 1990 however, did not commit itself fully to this identification, merely mentioning a Styracosaurus sp.[20] Rogers had joined the expedition in 1987.[21] This reflected the fact that the expedition members had started to take the possibility into account that the species was completely new to science, informally referring to it as "Styracosaurus makeli" in honour of Bob Makela, who had died in a traffic accident in June 1987.[22] In 1990, this name, as an invalid nomen nudum because it lacked a description, appeared in a photo caption in a book by Stephen Czerkas.[23]

Horner was an expert on the Hadrosauridae, several sites of which had also been discovered in Landslide Butte, including the juveniles and eggs that were the focus of his research. He had less affinity for other kinds of dinosaurs.[18] In 1987 and 1989, to resolve the Styracosaurus question, horned dinosaur specialist Peter Dodson was invited to investigate the new ceratopsian finds.[18] In 1990, the fossil material was seen by Dodson as strengthening the case for the validity of a separate Styracosaurus ovatus, to be distinguished from Styracosaurus albertensis.[24]

Horner had gradually changed his mind on the subject. While still thinking that a single population of horned dinosaurs had been present, he began to see it as a chronospecies, an evolutionary series of taxa. In 1992, he described them in an article as three "transitional taxa" that had spanned the gap between the older Styracosaurus and the later Pachyrhinosaurus. He deliberately declined to name these three taxa. The oldest form was indicated as "Transitional Taxon A", mainly represented by skull MOR 492. Then came "Taxon B" – the many skeletons of the Dinosaur Ridge Quarry and the Canyon Bone Bed. The youngest was "Taxon C", represented by skull MOR 485 found in 1987 and the horned dinosaur fossils of the Blacktail Creek North.[25]

Sampson names Einiosaurus

In 1994, Sampson, in a talk during the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, named Horner's "Taxon B" as a new genus and species, Einiosaurus procurvicornis. Although an abstract was published containing a sufficient description, making the name valid, it did not yet identify by inventory number a holotype, a name-bearing specimen. The same abstract named Type C as Achelousaurus horneri.[26] In 1995, Sampson published a larger article, indicating the holotype. The generic name Einiosaurus is derived from the Blackfeet eini, "American bison", and Latinised Greek saurus, "lizard". The name was chosen to honour the Blackfeet tribe but also to reflect the fact that ceratopsids were, in Sampson's words, "the buffalo of the Cretaceous", living in herds and having a complex life. According to Sampson, the name should be pronounced as "eye-knee-o-saurus". The specific name is derived from Latin procurvus, "bent forwards", and cornu, "horn", referring to the forwards curving nasal horn.[27]

The holotype, MOR 456-8-9-6-1, was found in a layer of the Two Medicine Formation dating from the late Campanian. It consists of a partial skull, including the nasal horn, the supraorbital area and part of the parietal bone of the skull frill. The skull represents an adult individual. Sampson referred many other specimens to the species. He indicated that additional fossil material from the Canyon Bone Bed had been subsumed under the inventory number MOR 456. This included two further adult skulls and single cranial and postcranial bones from individuals of varying age classes. Furthermore, the fossils from the Dino Ridge Quarry were referred. They had been catalogued within number MOR 373. They consisted of about two hundred non-articulated bones, again from animals of different ages.[27]

In 2010, Paul renamed E. procurvicornis into Centrosaurus procurvicornis,[28] but this has found no acceptance, subsequent research invariably referring to the taxon as Einiosaurus.

Description

Size and distinguishing traits

Einiosaurus was a herbivorous dinosaur. It is generally as large as Achelousaurus, though far less robust.[27] In 2010, Gregory S. Paul estimated the body length of Einiosaurus at 4.5 metres (15 ft), its weight at 1.3 tonnes (1.3 long tons; 1.4 short tons).[28] Both taxa fall within the typical size range of the Centrosaurinae.[27]

In 1995, Sampson indicated several distinguishing traits. The nasal horn has a base that is long from front to rear, is transversely flattened, and is strongly curved forwards in some adult specimens. The supraorbital "brow" horns as far as they are present are low and rounded with a convex surface on the inner side. The parietal parts of the rear edge of the skull frill together bear a single pair of large curved spikes sticking out to behind.[27]

Einiosaurus differs from all other known Centrosaurinae by a longer-based and more procurved nasal horn and by a supraorbital horn that is longer-based and more rounded in side view. It differs from Achelousaurus in particular in having large parietal spikes that are not directed sideways to some extent.[27]

As a centrosaurine, Einiosaurus walked on all fours, had a large head with a beak, a moderately large skull frill, a short powerful neck, heavily muscled forelimbs, a high torso, powerful hindlimbs and a relatively short tail.

Skeleton

In 1995, Sampson only described the skull, not the postcrania, the parts behind the skull. This was motivated by the fact that in centrosaurines the postcranial skeleton is "conservative", i.e. differs only slightly among species. Sampson could not find traits in which Einiosaurus differed from a generalised centrosaurine.[27]

The holotype skull is the largest known and has a total length of 1.56 metres (5.1 ft). The snout is relatively narrow and pointed. The top of the snout is formed by the paired nasal bones. Their top surfaces together bear the core of the nasal horn. In 1995, apart from the skulls eight nasal horns from both bonebeds were referred to Einiosaurus. Two of these were from subadults. These show how the horn developed during the growth of the animal. The initially separated core halves fused from the tip downwards and joined into a single structure on the midline. In the subadult stage, the core still showed a suture, however. The subadult cores were transversely flattened and relatively small, not higher than 12 centimetres (4.7 in). Six cores were of adults. They showed two distinctive types. Two cores were small and erect, i.e. vertically directed. The four others were large and procurved, strongly curving to the front. The adult horns resembled the subadult ones in being transversely compressed and having a long base from front to rear. To behind they nearly reached the frontal bones.[27]

Sampson compared the nasal horn of Einiosaurus with the horns of two related species, Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus. From large bonebeds, numerous nasal horns of Centrosaurus are known, presenting a considerable range of morphologies. Despite all this variation, Einiosaurus horns can be clearly distinguished from them. They are more laterally compressed, unlike the more oval cross-section of Centrosaurus horns. The adult horns are also much more procurved than any nasal horn found in Centrosaurus beds. Styracosaurus horncores are much longer than those of Einiosaurus, up to half a metre in length, and erect or slightly recurved to the rear.[27]

Apart from a horn on the snout, centrosaurines also had horns above the eye sockets, supraorbital horncores. These cores were formed by a fusion of the postorbital bone with the much smaller palpebral bone in front of it. Nine subadult or adult "brow horns" were found. They all shared the same build in being low, long and rounded. This differs from the usual pointed horns with an oval base seen in typical centrosaurines. It is also unlike the supraorbital bosses seen in Achelousaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus. Nevertheless, some Einiosaurus horns seemed to approach bosses. Three older individuals featured a total of five instances in which the horn as such was replaced by a low rounded mass, sometimes with a large pit in the usual location of the horn point. The large holotype has a rounded mass above the left eye socket but a pit, eighty-five millimetres long and sixty-four millimetres wide, on the right side. According to Sampson, this reflects a general trend with centrosaurines to re-absorb the brow horns in later life. All known specimens of Styracosaurus e.g. have a pitted region instead of true horns. The Einiosaurus holotype additionally has a rough bone mass at the rear postorbital region on the left side.[27] In all centrosaurines, the frontal bones re folded in such a way that a "double" roof is formed with a "supracranial cavity" in between. A fontanelle pierces the upper layer. In Einiosaurus, this cavity runs sideways, continuing to below into the brow horn. With Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus these passages are more narrow and do not reach the horns but Pachyrhinosaurus shows a comparable extension. Sampson in 1995 also expounded his general views on such skull roofs, which are not easy to interpret due to fusion. According to him, the frontal bones always extended to the parietals, so that the paired postorbitals never contacted. The parietal bone made only a small contribution to the fontanelle. The floor of the cavity is, at the frontal-parietal suture, pierced by a large foramen into the braincase, the function of this "pineal opening" being unknown.[27]

Its snout is narrow and very pointed. It is typically portrayed with a low, strongly forward and downward curving nasal horn that resembles a bottle opener, though this may only occur in some adults. The supraorbital (over-the-eye) horns are low, short and triangular in top view if present at all, as opposed to the chasmosaurines, such as Triceratops, which have prominent supraorbital horns. A pair of large spikes, the third epiparietals, projects backwards from the relatively small frill. Smaller osteoderms adorn the frill edge. The first epiparietals are largely absent.

Classification

The placement of Einiosaurus within Centrosaurinae is problematic due to the transitional nature of several of its skull characters, and its closest relatives are either Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus or Achelousaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus. The latter hypothesis is supported by Horner and colleagues, where Einiosaurus is the earliest of an evolutionary series in which the nasal horns gradually change to rough bosses, as in Achelousaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus which are the second and third in this series. The frills also grow in complexity.[29]

Regardless of which hypothesis is correct, Einiosaurus appears to occupy an intermediate position with respect to the evolution of the centrosaurines.

The cladogram presented below follows a phylogenetic analysis by Chiba et al. (2017):[30]

| Centrosaurinae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Low-diversity and single-species bonebeds are thought to represent herds that may have died in catastrophic events, such as during a drought or flood. This is evidence that Einiosaurus, as well as other centrosaurine ceratopsians such as Pachyrhinosaurus and Centrosaurus, were herding animals similar in behavior to modern-day bison or wildebeest. In contrast, ceratopsine ceratopsids, such as Triceratops and Torosaurus, are typically found singly, implying that they may have been somewhat solitary in life, though fossilized footprints may provide evidence to the contrary.[20] In 2010, a study by Julie Reizner of the individuals excavated at the Dino Ridge site concluded that Einiosaurus grew quickly until its third to fifth year of life after which growth slowed, probably at the onset of sexual maturity.[31]

Like all ceratopsids, Einiosaurus had a complex dental battery capable of processing even the toughest plants.[32] Einiosaurus lived in an inland habitat.[33]

Paleoecology

Einiosaurus fossils are found in the upper part of the Two Medicine Formation of Montana, dating to the mid-late Campanian stage of the late Cretaceous Period, about 74.5 million years ago.[34][35] Dinosaurs that lived alongside Einiosaurus include the basal ornithopod Orodromeus, hadrosaurids (such as Hypacrosaurus, Maiasaura, and Prosaurolophus), the centrosaurines Brachyceratops and Stellasaurus, the leptoceratopsid Cerasinops, the ankylosaurs Edmontonia and Euoplocephalus, the tyrannosaurid Daspletosaurus (which appears to have been a specialist of preying on ceratopsians), as well as the smaller theropods Bambiraptor, Chirostenotes, Troodon, and Avisaurus. Einiosaurus lived in a climate that was seasonal, warm, and semi-arid. Other fossils found with the Einiosaurus material include freshwater bivalves and gastropods, which imply that these bones were deposited in a shallow lake environment.

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 57.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 61.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 64.

- 1 2 Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 65.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 75.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 74.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 79.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 80.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 84.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 82.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 103.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 104.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, pp. 110–111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dodson, P. (1996). The Horned Dinosaurs: a Natural History. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 193–197. ISBN 978-0691628950.

- ↑ Dodson, P.; Forster, C.A.; Sampson, S.D., 2004, "Ceratopsidae", in: Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H., The Dinosauria, Second Edition, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 494–513

- 1 2 Rogers (1990).

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, p. 85.

- ↑ Horner & Dobb 1997, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Czerkas, S. J.; Czerkas, S. A. (1990). Dinosaurs: a Global View. Limpsfield: Dragons’ World. p. 208. ISBN 978-0792456063.

- ↑ Dodson, P.; Currie, P. J. (1990). "Neoceratopsia". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2 ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 593–618. ISBN 978-0520254084.

- ↑ Horner, J. R.; Varricchio, D. J.; Goodwin, M. B. (1992). "Marine transgressions and the evolution of Cretaceous dinosaurs". Nature. 358 (6381): 59–61. Bibcode:1992Natur.358...59H. doi:10.1038/358059a0. S2CID 4283438.

- ↑ Sampson, S. D. 1994. "Two new horned dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation, Montana, USA". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14(3, supplement): 44A

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sampson (1995).

- 1 2 Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 262

- ↑ Horner, et al. (1992).

- ↑ Kentaro Chiba; Michael J. Ryan; Federico Fanti; Mark A. Loewen; David C. Evans (2018). "New material and systematic re-evaluation of Medusaceratops lokii (Dinosauria, Ceratopsidae) from the Judith River Formation (Campanian, Montana)". Journal of Paleontology. 92 (2): 272–288. doi:10.1017/jpa.2017.62. S2CID 134031275.

- ↑ Reizner, J., 2010, An ontogenetic series and population histology of the ceratopsid dinosaur Einiosaurus procurvicornis. Montana State University master's thesis, pp 97

- ↑ Dodson, et al. (2004).

- ↑ "Judithian Climax," Lehman (2001); page 315.

- ↑ Andrew T. McDonald & John R. Horner, (2010). "New Material of "Styracosaurus" ovatus from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana". Pages 156–168 in: Michael J. Ryan, Brenda J. Chinnery-Allgeier, and David A. Eberth (eds), New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN.

- ↑ Fiorillo, A.R. and Tykoski, R.S.T. (in press). "A new species of the centrosaurine ceratopsid Pachyrhinosaurus from the North Slope (Prince Creek Formation: Maastrichtian) of Alaska." Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, available online 26 Aug 2011. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0033

References

- Dodson, P., Forster, C.A. and Sampson, S.D. (2004). "Ceratopsidae." In, Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., and Osmolska, H. (eds.), The Dinosauria. 2nd Edition, University of California Press.

- Horner, J.R.; Varricchio, D.J.; Goodwin, M.J. (1992). "Marine transgressions and the evolution of Cretaceous dinosaurs". Nature. 358 (6381): 59–61. Bibcode:1992Natur.358...59H. doi:10.1038/358059a0. S2CID 4283438.

- Lehman, T. M., 2001, Late Cretaceous dinosaur provinciality: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 310–328.

- Rogers, R.R. (1990). "Taphonomy of three dinosaur bone beds in the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of northwestern Montana: evidence for drought-related mortality". PALAIOS. 5 (5): 394–413. Bibcode:1990Palai...5..394R. doi:10.2307/3514834. JSTOR 3514834.

- Sampson, S.D. (1995). "Two new horned dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana; with a phylogenetic analysis of the Centrosaurinae (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 15 (4): 743–760. doi:10.1080/02724634.1995.10011259.

- Horner, J. R.; Dobb, E. (1997), Dinosaur Lives: Unearthing an Evolutionary Saga, San Diego, New York, London: Hartcourt Brace & Company

External links

- Einiosaurus at The Dinosaur Picture Database

.png.webp)