Elizabeth City, North Carolina | |

|---|---|

Elizabeth City facing the Pasquotank River | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Harbor of Hospitality,[1] Best City in the 252, Betsy City, E.C., Queen of the Albemarle, River City | |

Location in Pasquotank County in the state of North Carolina | |

| Coordinates: 36°17′39″N 76°14′16″W / 36.29417°N 76.23778°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | North Carolina |

| Counties | Pasquotank, Camden |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Edward Kirk Rivers |

| Area | |

| • City | 11.71 sq mi (30.32 km2) |

| • Land | 11.71 sq mi (30.32 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 18,631 |

| • Density | 1,591.58/sq mi (614.50/km2) |

| • Metro | 63,270 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 27906, 27907, 27909 |

| Area code | 252 |

| FIPS code | 37-20580[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2403551[3] |

| Website | www |

Elizabeth City is a city in Pasquotank and Camden counties, North Carolina, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 18,629.[5] Elizabeth City is the county seat and most populous city of Pasquotank County.[6] It is the cultural, economic and educational hub of the sixteen-county Historic Albemarle region of northeastern North Carolina.[7]

Elizabeth City is the center of the Elizabeth City Micropolitan Statistical Area, with a population of 64,094 as of 2010. It is part of the larger Virginia Beach-Norfolk, VA-NC Combined Statistical Area.[8] The city is the economic center of the region, as well as home to many historic sites and cultural traditions.

Marketed as the "Harbor of Hospitality", Elizabeth City has had a long history of shipping due to its location at a narrowed bend of the Pasquotank River.[9] Founded in 1794, Elizabeth City prospered early on from the Dismal Swamp Canal as a mercantile city. Later it developed industry and other commercial focus. While Elizabeth City still retains extensive waterfront property, it is linked to neighboring counties and cities by contemporary highways and bridges to support other transportation. It hosts one of the largest United States Coast Guard bases in the nation.

History

Located at the narrows of the Pasquotank River, colonists used the area that developed as Elizabeth City as a trading site. As early as the mid 18th century, they established inspection stations and ferries. With the addition of minor roads, a schoolhouse, and soon a church, a small community developed at these narrows.[10]

In 1793, businessmen supported construction of the Dismal Swamp Canal; it was integral to the success of Elizabeth City's commerce. The North Carolina Assembly incorporated the town as "Redding", renaming it in 1794 as "Elizabethtown". Due to resulting confusion with another town of the same name, in 1801, the city was renamed as "Elizabeth City".[11] The name "Elizabeth" has been attributed to Elizabeth "Betsy" Tooley, a local tavern proprietress who donated much of the land for the new town.[12]

With improvements to the Dismal Swamp Canal, commerce flourished and Elizabeth City became a financial center of trade and commercially successful in the early 19th century. In 1826, the federal government purchased 600 stocks in the canal and, in 1829, additional funds for improvements were raised by the Norfolk lottery. With these funds, the Dismal Swamp Canal was widened and deepened, allowing for larger boats to ship their goods to and from the city.

Further bolstering Elizabeth City's financial success, the US customs house was relocated in 1827 from Camden County to Elizabeth City. From 1829 to 1832, Elizabeth City's tolls tripled for commercial shipping.

During the American Civil War, the Confederate States had a small fleet stationed at Elizabeth City. After the Battle of Roanoke Island, Union forces sent a fleet to take the city. A small skirmish resulted in a Union victory. Elizabeth City was under Union control for the remainder of the war, as was most of coastal North Carolina. Confederate irregulars engaged in guerrilla warfare with Union forces in the area for the remainder of the war.

.jpg.webp)

Meanwhile, overland travel slowly improved, enabling greater trade between neighboring counties. The ferry continued to provide transport between Elizabeth City and Camden County. But the completion of competing canals and railroads around Elizabeth City meant that neighboring cities began to draw off some of the traffic. The Portsmouth and Weldon Railroad, completed in the 1830s, allowed for goods to be transported from the Roanoke River directly to Weldon. The Albemarle–Chesapeake Canal, completed in 1859, created a deeper channel for merchants shipping goods from the eastern Albemarle Sound to Norfolk.

Such new opportunities established Elizabeth City as a thriving deep-water port and powerful regional economic center. It was based on such industries as lumbering, shipbuilding, grain export, and fish and oyster processing; it rivaled other ports such as Norfolk, Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland. But the establishment in 1881 of the Elizabeth City and Norfolk Railroad, later renamed the Norfolk Southern Railway, encouraged a shift of industries from waterfront in Elizabeth City to the growing cities of North Carolina's Upper Coastal Plain and Piedmont.[13]

The declaration of World War II reinvigorated Elizabeth City's industries, particularly in shipbuilding, textiles, and aeronautics. Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City was established in 1940 and Navy Air Station Weeksville in 1941 to provide valuable surveillance by seaplane and dirigible of German U-boats that were targeting American merchant shipping in East Coast waters.

Additionally from 1942 to 1944, the Elizabeth City Shipyard supported the war effort with much of its production: thirty 111-foot SC-class submarine chasers,[14][15][16] four YT-class yard tugboats, and six 104-foot QS-class quick supply boats.[14][17] The Elizabeth City Shipyard built the most subchasers for the war effort (30 out of 438 total nationally), and set the record construction time for the SC-class, with SC-740 laid down in only thirty days.[15] As of June 2013, the Elizabeth City Shipyard is still in operation.

For two years, 1950 and 1951, Elizabeth City was home to a professional minor league baseball team. The Elizabeth City Albemarles played in the Class D level Virginia League. Previously, the town had fielded a team for several seasons in the semipro Albemarle League.[18]

The conclusion of the war led to a levelled economy. Industry restructuring here and in other areas changed the economy. Since the late 20th century, the service, government, and agriculture sectors have become dominant in the current economy. Starting in the late 1990s, revival efforts in tourism and civic revitalization centered on downtown and the city's five historic districts have led to increasing economic stability.

The Elizabeth City Historic District, Elizabeth City State Teachers College Historic District, Elizabeth City Water Plant, Episcopal Cemetery, Norfolk Southern Passenger Station, Northside Historic District, Old Brick House, Riverside Historic District, and Shepard Street-South Road Street Historic District are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[19] They are protected to encourage heritage tourism that stresses the city's unique qualities.

Geography

Elizabeth City is located alongside the Pasquotank River, which connects to Albemarle Sound. Directly across the river lies Camden County.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Elizabeth City has a total area of 12.2 square miles (31.7 km2), of which 11.6 square miles (30.1 km2) is land and 0.62 square miles (1.6 km2), or 5.09%, is water.[20] Located in the "Inner Banks" region of North Carolina, Elizabeth City is largely flat and marshy with an elevation of only 12 feet (3.7 m) above sea level.[21] The city's semi-coastal geography has played an important role in its history—Elizabeth City once hosted thriving oyster and timber industries.

Climate

Elizabeth City has a humid subtropical climate, experiencing only modest seasonal variation in temperature and precipitation. Because it is relatively close to the Albemarle Sound and the Atlantic Ocean, the temperature variations in the area are somewhat softened. On average, Elizabeth City has its highest temperature and accumulation of precipitation in July. Elizabeth City commonly experiences thunderstorms during the summer months and has endured many tropical storms and hurricanes due to its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. This city experiences very little snowfall, however, receiving on average a total of 3.5 inches (89 mm) of snow annually.[22]

| Climate data for Elizabeth City, North Carolina (1991–2020 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1911–2022) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

82 (28) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

101 (38) |

104 (40) |

107 (42) |

104 (40) |

99 (37) |

95 (35) |

90 (32) |

82 (28) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 71.9 (22.2) |

73.3 (22.9) |

80.0 (26.7) |

85.2 (29.6) |

90.9 (32.7) |

95.0 (35.0) |

96.1 (35.6) |

94.5 (34.7) |

90.8 (32.7) |

85.8 (29.9) |

78.7 (25.9) |

72.9 (22.7) |

97.3 (36.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 53.2 (11.8) |

56.2 (13.4) |

63.2 (17.3) |

72.2 (22.3) |

78.9 (26.1) |

85.8 (29.9) |

88.9 (31.6) |

87.3 (30.7) |

82.2 (27.9) |

74.1 (23.4) |

64.0 (17.8) |

56.4 (13.6) |

71.9 (22.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 43.4 (6.3) |

45.4 (7.4) |

52.1 (11.2) |

61.3 (16.3) |

68.9 (20.5) |

77.1 (25.1) |

80.7 (27.1) |

79.1 (26.2) |

74.1 (23.4) |

64.4 (18.0) |

53.8 (12.1) |

47.0 (8.3) |

62.3 (16.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.6 (0.9) |

34.7 (1.5) |

41.1 (5.1) |

50.4 (10.2) |

58.9 (14.9) |

68.4 (20.2) |

72.5 (22.5) |

70.9 (21.6) |

66.0 (18.9) |

54.7 (12.6) |

43.7 (6.5) |

37.6 (3.1) |

52.7 (11.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 15.5 (−9.2) |

19.3 (−7.1) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

32.7 (0.4) |

42.6 (5.9) |

52.9 (11.6) |

61.8 (16.6) |

60.0 (15.6) |

51.8 (11.0) |

38.0 (3.3) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

13.1 (−10.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

5 (−15) |

11 (−12) |

17 (−8) |

22 (−6) |

39 (4) |

49 (9) |

47 (8) |

39 (4) |

24 (−4) |

17 (−8) |

−3 (−19) |

−3 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.64 (92) |

3.29 (84) |

4.17 (106) |

3.47 (88) |

4.07 (103) |

4.49 (114) |

5.93 (151) |

5.91 (150) |

5.32 (135) |

3.70 (94) |

3.39 (86) |

3.88 (99) |

51.26 (1,302) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.1 (0.25) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.5 | 10.2 | 11.1 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 9.2 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 9.6 | 7.8 | 8.7 | 11.4 | 120.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Source: NOAA[23][24] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Elizabeth City (Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City), North Carolina (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1948–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

85 (29) |

93 (34) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

104 (40) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

96 (36) |

85 (29) |

81 (27) |

104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 72.9 (22.7) |

74.4 (23.6) |

81.0 (27.2) |

85.8 (29.9) |

90.1 (32.3) |

94.9 (34.9) |

95.6 (35.3) |

94.4 (34.7) |

90.7 (32.6) |

86.5 (30.3) |

79.0 (26.1) |

73.9 (23.3) |

96.8 (36.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 52.3 (11.3) |

55.0 (12.8) |

61.3 (16.3) |

70.8 (21.6) |

78.0 (25.6) |

85.4 (29.7) |

88.2 (31.2) |

86.8 (30.4) |

81.8 (27.7) |

73.4 (23.0) |

63.1 (17.3) |

55.6 (13.1) |

71.0 (21.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 42.7 (5.9) |

45.0 (7.2) |

50.9 (10.5) |

60.1 (15.6) |

68.2 (20.1) |

76.2 (24.6) |

79.6 (26.4) |

78.4 (25.8) |

73.4 (23.0) |

63.1 (17.3) |

52.7 (11.5) |

46.0 (7.8) |

61.4 (16.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.1 (0.6) |

35.0 (1.7) |

40.5 (4.7) |

49.4 (9.7) |

58.4 (14.7) |

67.1 (19.5) |

71.0 (21.7) |

70.0 (21.1) |

64.9 (18.3) |

52.8 (11.6) |

42.4 (5.8) |

36.5 (2.5) |

51.8 (11.0) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 16.1 (−8.8) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

33.8 (1.0) |

44.7 (7.1) |

54.5 (12.5) |

61.5 (16.4) |

60.0 (15.6) |

52.1 (11.2) |

36.9 (2.7) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

14.5 (−9.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 2 (−17) |

8 (−13) |

18 (−8) |

27 (−3) |

35 (2) |

45 (7) |

51 (11) |

49 (9) |

41 (5) |

26 (−3) |

19 (−7) |

9 (−13) |

2 (−17) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.30 (84) |

2.87 (73) |

3.59 (91) |

3.16 (80) |

3.68 (93) |

4.71 (120) |

5.65 (144) |

5.32 (135) |

4.52 (115) |

3.63 (92) |

2.97 (75) |

3.11 (79) |

46.51 (1,181) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.0 | 9.9 | 10.5 | 9.3 | 11.0 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 11.8 | 9.8 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 9.9 | 120.1 |

| Source: NOAA[23][25] | |||||||||||||

- Notes

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said thread from 1991 to 2020

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 930 | — | |

| 1880 | 2,315 | 148.9% | |

| 1890 | 3,251 | 40.4% | |

| 1900 | 6,348 | 95.3% | |

| 1910 | 8,412 | 32.5% | |

| 1920 | 8,925 | 6.1% | |

| 1930 | 10,037 | 12.5% | |

| 1940 | 11,564 | 15.2% | |

| 1950 | 12,685 | 9.7% | |

| 1960 | 14,062 | 10.9% | |

| 1970 | 14,381 | 2.3% | |

| 1980 | 14,004 | −2.6% | |

| 1990 | 14,292 | 2.1% | |

| 2000 | 17,188 | 20.3% | |

| 2010 | 18,683 | 8.7% | |

| 2020 | 18,629 | −0.3% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 18,703 | [5] | 0.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26][27] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 6,852 | 36.78% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 9,332 | 50.09% |

| Native American | 71 | 0.38% |

| Asian | 220 | 1.18% |

| Pacific Islander | 11 | 0.06% |

| Other/Mixed | 845 | 4.54% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,300 | 6.98% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 18,631 people, 6,526 households, and 3,839 families residing in the city.

2010 census

According to the 2010 U.S. Census,[4] there were 18,683 people, 7,487 households, and 4,689 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,607.0 inhabitants per square mile (620.5/km2). There were 8,167 housing units at an average density of 702.24 per square mile (271.14/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 54.00% African American, 39.50% White, 0.40% Native American, 1.20% Asian, 0.10% Pacific Islander, 0.62% from other races, and 2.30% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.00% of the population.

There were 6,577 households, out of which 32.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.0% were married couples living together, 22.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.6% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 27.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.7% under the age of 19, 12.1% from 20 to 24, 23.1% from 25 to 44, 22.1% from 45 to 64, and 13.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 81.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 68.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $34,582, and the median income for a family was $41,071. Males had a median income of $31,307 versus $25,683 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,592. About 21.6% of families and 28.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 42.5% of those under age 18 and 12.1% of those age 65 or over. [29]

Government

Elizabeth City serves as the county seat of Pasquotank County. The city has a council–manager style of government. The city council is composed of eight council members and the city manager, elected by the council members. The city manager serves a largely executive function, overseeing the city's administrative departments, appointing department heads and city employees, and informing the rest of the council of relevant municipal conditions. Currently, the city manager is Rich Olsen.[30] The eight council members, on the other hand, act in a legislative regard, adopting city policies, holding the city manager responsible, and choosing a mayor pro-tempore from its council members. This council is elected every two years by each of the four wards composing the city electing two members.[9]

The mayor, elected by the whole voter body every two years, also serves an executive function, serving as the head of a council meeting and casting a tie-breaking vote for the council. As of 2016, the mayor is Betty Parker. Previous mayors include Joseph Peel, Charles L. Foster, who served from 2005 to 2007, and John Bell, who served from 1971 to 1981 and again from 2001 to 2005.[31]

The council holds its meetings every second and fourth Monday of the month; the meetings are rebroadcast on a public service channel.[9]

Elizabeth City has an office for the United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, headed by Terrence W. Boyle as the resident judge. This court presides over cases in the northern region of this district.[32]

Elizabeth City also occupies North Carolina's 3rd congressional district, served by U.S. Representative Greg Murphy.[33]

U.S. Coast Guard

Established in 1940 and located southeast of Elizabeth City's corporate limits, Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City is one of the largest United States Coast Guard Air Stations in the nation at over 800 acres,[34] and is home to six commands - Air Station Elizabeth City, Aviation Logistics Center, Aviation Technical Training Center, Base Elizabeth City,[35] C-27J Asset Project Office (APO), and Small Boat Station Elizabeth City - as well as the off-base National Strike Force Coordination Center located in northern Elizabeth City. As a component of the United States Department of Homeland Security, the base, along with a host of defense contractors anchored by DRS Technologies, provide a host of local jobs and maintains an influx of Coast Guard and industry employees from all around the country.

The USCG Air Station and the Aviation Technical Training Center (ATTC) in Elizabeth City were featured in numerous scenes of the 2006 Disney movie The Guardian, standing in for Kodiak, Alaska.

Elizabeth City is also home to one of the United States' few airship factories.[36] Many of the nation's commercial blimps are made and serviced here. The current airship facilities evolved from what had previously been Naval Air Station Weeksville, operational from 1941 to 1957. NAS Weeksville's LTA craft played a vital role in German U-boat spotting during World War II, helping to minimize losses to East Coast shipping.[37] NAS Weeksville was home to two hangars, one still existing as corrugated steel, and a slightly larger one constructed out of Southern Yellow Pine, to conserve metal for the WWII war effort. This latter hangar was the largest wooden structure in the world until its demise by fire in 1995.

A joint public-private airpark adjacent to the Coast Guard base is in the planning stages. Intended to make Elizabeth City a premier hub of the aviation industry, the airpark hopes to attract major tenants as well as the Aviation Science programs of Elizabeth City State University and related programs by the College of the Albemarle.

Arts and culture

Elizabeth City is home to the Museum of the Albemarle, the northeastern regional branch of the North Carolina Museum of History. The museum occupies a prominent location adjacent to the city's waterfront and contains many permanent and revolving exhibits on the history and culture of the historic Albemarle region. The history of European colonization dates back to 1668, making the Albemarle the country's oldest colonial inhabited area, second only to Jamestown and adjacent settlements in neighboring Virginia.

Downtown Elizabeth City is also home to Arts of the Albemarle, a regional arts council located in the Lowery-Chesson Building. Once home to the Chesson Department Store on the ground floor and a turn-of-the-century opera house on the second and third floors, the once-dilapidated building undertook a $3.4 million renovation, and "The Center" became AOA's permanent home in 2005. The three-story building houses three art galleries, the state-of-the-art McGuire Theater for the performing arts, and multiple conference and meeting rooms. The Center has been an economic driver for downtown Elizabeth City since its opening.

Among these are the most striking architectural feature of the greater Albemarle region, the Virginia Dare Hotel, and Arcade, which has dominated the skyline of Elizabeth City since its completion in 1927. Designed by William Lee Stoddart of New York City, one of the nation's leading hotel architects, the nine-story building was billed as the Albemarle's first “skyscraper” when it opened in 1927. It remains the tallest building in the region.

The hotel contained 100 rooms and a heated garage (now the rear parking lot) with an interior filling station and lubricating stand. It remained the premier hotel and center of Elizabeth City's social activities for over 40 years. Architecturally, its restrained Colonial Revival finish follows the typical division of such tall buildings into the three parts of a classical pillar: a sturdy two-story base; a simply detailed six-story shaft; and a one-story capital, which displays an abundance of decoration. Today it serves as an elderly apartment complex.[38]

Elizabeth City has been the birthplace of a few government officials in its history. Judge John Warren Davis, a justice of the Federal Court of Appeals, was born in Elizabeth City, as was John C. B. Ehringhaus, governor of North Carolina from 1933 to 1937 and for whom Ehringhaus Street, a major thoroughfare, is named.[13]

During the same era, nine-ball legend Luther Lassiter was born in Elizabeth City, and developed much of his skill at pool in the City Billiards pool hall.[39]

Elizabeth City was the 1929 birthplace of the American Moth Boat, a class of recreational sailboats invented by Dr. Joel Van Sant. The city hosts a Moth Boat Regatta annually in late February.[40][41] The Moth Boat features prominently on the city's seal.

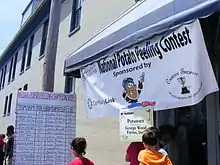

North Carolina Potato Festival

Elizabeth City hosts the North Carolina Potato Festival, an annual celebration of the potato, one of the region's most important crops. The festival has steadily become one of the most popular draws in northeastern North Carolina, and is usually held in mid-May in downtown Elizabeth City.[42]

Albemarle Craftsman's Fair

This annual Christmastime fair is sponsored by the Albemarle Craftsman's Guild and features artisans, many of whom wear period costumes, selling and demonstrating traditional crafts. Crafts include quilting and fiber arts, pottery, jewelry and woodwork.[43][44]

Juneteenth Celebration

This annual celebration is sponsored by River City Community Development Corporation and celebrates the freeing of African Slaves in America. It has evolved into a multi-racial, multi-cultural celebration of American Freedom. The festival features vendors and informational booths, speakers, entertainment, and good food.[45]

Elizabeth City is mentioned in the novel The Scarlet Thread by Rachel L. Vaughan.

Media

The Daily Advance has served as Elizabeth City's sole daily newspaper since its founding by Herbert Peele in 1911.[46] In mid-2009, the Daily Advance was bought by Cooke Communications.[47]

The Independent was a weekly newspaper serving Elizabeth City and the surrounding Albemarle area from 1908 to 1939. The Independent was published by William Oscar "W.O." Saunders (1884-1940).[48]

Elizabeth City is part of the Hampton Roads television market. The majority of the stations received in the area come from southeastern Virginia, including WTKR (CBS), WAVY (NBC), WVEC (ABC), WVBT (FOX), and WHRO (PBS).

The only exceptions are WUND (PBS), a repeater transmitter of UNC-TV licensed to broadcast from Edenton, North Carolina, and WSKY (independent) transmitting from Camden. The only station based in Elizabeth City is W18BB-D, broadcasting from a tower on the Elizabeth City State University campus.

Education

All public education is overseen by the Elizabeth City-Pasquotank County School Board of Education under the Elizabeth City-Pasquotank Public School system (ECPPS) which operates seven elementary schools, two middle schools, two high schools, one Early College program, one alternative high school and one public charter STEM school[49]

Elementary schools

- Central Elementary

- J.C. Sawyer Elementary

- Northside Elementary

- Pasquotank Elementary

- P.W. Moore Elementary

- Sheep-Harney Elementary

- Weeksville Elementary

Middle schools

- Elizabeth City Middle

- River Road Middle

High schools

- Northeastern High

- Pasquotank County High

- Elizabeth City-Pasquotank Early College

Alternative school

- H.L. Trigg Alternative

Public Charter STEM School

- Northeast Academy for Aerospace and Advanced Technologies (NEAAAT)

Private schools

- Albemarle School

- Cathedral Christian Academy

- Foreshadow Academy

- Grace Montessori Academy

- New Life Academy

- Victory Christian School

Higher education

Elizabeth City is home to one private and two public institutions of higher education.

Elizabeth City State University, the smallest constituent member of the 16-campus University of North Carolina System, is a historically African-American institution, enrolling 2,930 students as of fall 2011[50] on a compact 200-acre (0.81 km2) campus along the city's southern edge. Founded as a normal school in 1891, it now serves the higher educational needs of northeastern North Carolina's sixteen counties, offering 28 undergraduate and four master's degrees.[51]

ECSU offers Aviation Science programs at their training facility at Elizabeth City Regional Airport,[52] as well as a Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) program in collaboration with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH), flagship school of the UNC system.[53]

Also located here is the main campus of the College of the Albemarle (COA), positioned on the city's northern edge adjacent to Albemarle Hospital. It is known as the first community college to be established under the (North Carolina) Community College Act of 1960. COA has satellite campuses in Barco, Edenton and Manteo.[54]

Mid-Atlantic Christian University, a private Christian institution founded in 1948, is located along the Pasquotank River north of downtown Elizabeth City.

All three schools have agreements allowing students to dual-enroll in one of the other two institutions.

Healthcare

The primary healthcare provider in Elizabeth City is Sentara Albemarle Medical Center, a 182-bed regional medical center and part of the Sentara Healthcare system. Owned and formally operated by Pasquotank County, Albemarle Hospital has been in operation since 1914,[55] relocating to its current location in 1960. In 2008, the Albemarle Health system came under the day-to-day management of Greenville-based Vidant Health, although ownership and most executive decisions remained with the county.

Starting in October 2012, the county began soliciting offers for affiliation with neighboring healthcare systems in order to cement Albemarle Hospital's position as the region's major medical facility. Limitations in some services and specialty providers had caused many prospective patients to seek services in the Hampton Roads or Greenville metro areas, leading to steady erosion of operating margins. Affiliation with a larger health organization would also provide increased buying power, improvements in equipment and facility investment as well as entice additional physicians to the area.[56]

By January 2013 the board had received strong offers from then-current manager Vidant Health as well as Norfolk-based Sentara Healthcare and Brentwood, Tennessee-based Duke-LifePoint Health, itself a partnership between Durham-based Duke University Health System and Brentwood-based LifePoint Hospitals.[57]

A 100-year management agreement for operation of the Albemarle Health system was reached with Sentara Healthcare, becoming effective on March 1, 2014, with Sentara committing to streamline patient care as well as make substantial investments in the physical building itself.

Services and utilities

As part of its municipal mandate, Elizabeth City operates full-service police (ECPD), fire (ECFD) and public housing departments as well as water, sewer, sanitation and electric divisions which operate several deep wells, a water purification plant, three water towers, and a combined sewage/wastewater treatment plant.[58] The city cooperates with Pasquotank County in joint operation of the Elizabeth City-Pasquotank Parks and Recreational Department (ECPPRD), Department of Social Services (ECPDSS), and the Witherspoon Memorial Library, the largest facility and head office of the four-county East Albemarle Regional Library System.[59]

As with other Albemarle-area municipalities, Elizabeth City purchases wholesale electricity from Dominion North Carolina Power, operating 230kV transmission lines through the Albemarle area.[60] Electricity is generated from natural gas-fired and nuclear power plants in nearby Chesapeake and Surry, Virginia, respectively.[61]

Electricity is also locally generated for export by solar and wind facilities in Pasquotank County by Dominion Energy's Morgan's Corner 110 acre, 20MW solar farm, and Avangrid Renewables' Amazon Wind Farm East 22,000 acre (200 acre footprint), 208MW wind farm. Other renewable energy production facilities, chiefly solar, also exist in neighboring counties.[62][61]

Local telephone service is currently provided by CenturyLink, operating out of the former headquarters and switchboard exchange building of early Elizabeth City-based provider Norfolk and Carolina Telephone and Telegraph.[63] N&CT&T was later succeeded by Carolina Telephone & Telegraph, United Telecom, Sprint and Embarq.

Cable television and Internet is provided by Time Warner, previously Adelphia Communications.

Pipeline natural gas is provided by Piedmont Natural Gas. Tank and bottled gas are also available through several local suppliers.

Transportation

Highways

Elizabeth City is linked to neighboring counties and cities through a network of highways.

Most unusual are the four branches of U.S. Route 17 that pass through the city - rarely are there more than two or three variants of the same route in any given community.

Mainline ![]() US 17 crosses the Little River, entering Pasquotank County from the southwest. Bypass US 17 immediately splits off to the northwest as mainline US 17 continues to the northeast toward Elizabeth City. Shortly after entering the city limits, US 17 Business splits off to the east towards the downtown waterfront. Mainline US 17 continues through Elizabeth City as Hughes Boulevard (the former US 17 Bypass from 1969 to 2002).

US 17 crosses the Little River, entering Pasquotank County from the southwest. Bypass US 17 immediately splits off to the northwest as mainline US 17 continues to the northeast toward Elizabeth City. Shortly after entering the city limits, US 17 Business splits off to the east towards the downtown waterfront. Mainline US 17 continues through Elizabeth City as Hughes Boulevard (the former US 17 Bypass from 1969 to 2002).

The route encounters major intersections with the commercial corridor of NC 344 (Halstead Boulevard), Church Street, Main Street and midway by Elizabeth Street, where it is joined by US 158 and Truck Business US 17. This tri-route combination continues northeastward to Business 17 and Truck Business 17's northern termini at the intersection with North Road Street. From here, mainline US 17 and 158 make a curve to the northwest, departing Elizabeth City as a continuance of North Road Street.

Bypass US 17 rejoins the highway several miles outside of town, while US 158 splits off to the west at Morgan's Corner just before crossing the Pasquotank River into Camden County. Running parallel to the Dismal Swamp Canal and the eastern boundary of the Great Dismal Swamp, US 17 continues to the Virginia border.

![]()

![]() US 17 Bus. (1969–present) branches off Hughes Boulevard and travels east as Ehringhaus Street, named for Governor John C. B. Ehringhaus (1933-1937), the only governor native to Elizabeth City. The route turns north through Downtown as North Road Street, ending with its intersection with US 17/Hughes Boulevard. Mainline US 17 continues north on North Road Street.

US 17 Bus. (1969–present) branches off Hughes Boulevard and travels east as Ehringhaus Street, named for Governor John C. B. Ehringhaus (1933-1937), the only governor native to Elizabeth City. The route turns north through Downtown as North Road Street, ending with its intersection with US 17/Hughes Boulevard. Mainline US 17 continues north on North Road Street.

![]()

![]() US 17 Bus. Truck is a double-designation almost unique among U.S. routes, traveling from the Camden Causeway west along Elizabeth Street and north along Hughes Boulevard to double-terminate with US 17 Business. The northern segment of US 17 Business from Elizabeth Street to its termination at Hughes Boulevard runs through a residential district and additionally has weight restrictions, thus requiring an alternate business routing.

US 17 Bus. Truck is a double-designation almost unique among U.S. routes, traveling from the Camden Causeway west along Elizabeth Street and north along Hughes Boulevard to double-terminate with US 17 Business. The northern segment of US 17 Business from Elizabeth Street to its termination at Hughes Boulevard runs through a residential district and additionally has weight restrictions, thus requiring an alternate business routing.

![]()

![]() US 17 Byp. (2002–present) is a fully access-controlled and Interstate-grade freeway. Completed in 2002, US 17 Bypass stretches 9.3 miles to the immediate west of the city, eliminating one of the last remaining inner-city stretches of US 17 in North Carolina. In combination with other bypasses on U.S. 17 from the Virginia border to Williamston, the Elizabeth City bypass forms an integral component in the future I-87.

US 17 Byp. (2002–present) is a fully access-controlled and Interstate-grade freeway. Completed in 2002, US 17 Bypass stretches 9.3 miles to the immediate west of the city, eliminating one of the last remaining inner-city stretches of US 17 in North Carolina. In combination with other bypasses on U.S. 17 from the Virginia border to Williamston, the Elizabeth City bypass forms an integral component in the future I-87.

![]() US 158 enters Elizabeth City from points east, including the Outer Banks, as well as Dare, Currituck, and Camden counties. Traveling westward through town as Elizabeth Street, US 158 temporarily merges with mainline and Truck Business US 17 along the Hughes Boulevard and North Road Street corridors. It continues traveling northwestward leaving the city limits, turning left at Morgan's Corner and continuing westward across the Great Dismal Swamp into Gates County.

US 158 enters Elizabeth City from points east, including the Outer Banks, as well as Dare, Currituck, and Camden counties. Traveling westward through town as Elizabeth Street, US 158 temporarily merges with mainline and Truck Business US 17 along the Hughes Boulevard and North Road Street corridors. It continues traveling northwestward leaving the city limits, turning left at Morgan's Corner and continuing westward across the Great Dismal Swamp into Gates County.

![]() NC 344 forms a minor connection southeastward from the US 17 Bypass to southern Pasquotank County. NC 344 serves as a major commercial and industrial corridor along Elizabeth City's southern edge, providing access to Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City, Elizabeth City State University, and the rural unincorporated community of Weeksville.

NC 344 forms a minor connection southeastward from the US 17 Bypass to southern Pasquotank County. NC 344 serves as a major commercial and industrial corridor along Elizabeth City's southern edge, providing access to Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City, Elizabeth City State University, and the rural unincorporated community of Weeksville.

Future

![]()

![]() Future I-87 is planned to connect Elizabeth City to the Interstate Highway System; when completed, it will run from Raleigh to Norfolk, Virginia, utilizing existing segments of US 64, US 13 and US 17, upgrading them to fully controlled access Interstate highway standards.

Future I-87 is planned to connect Elizabeth City to the Interstate Highway System; when completed, it will run from Raleigh to Norfolk, Virginia, utilizing existing segments of US 64, US 13 and US 17, upgrading them to fully controlled access Interstate highway standards.

Air

Elizabeth City has a joint civil-military airport, shared with U.S. Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City, and located 4 miles (6 km) southeast of the city limits, named the Elizabeth City Regional Airport (IATA: ECG, ICAO: KECG, FAA LID: ECG).

Scheduled domestic and international passenger services are available at Norfolk International Airport (IATA: ORF, ICAO: KORF, FAA LID: ORF), located about an hour north in Norfolk, Virginia.

Bus

Local public bus transportation is provided by the Inter-County Public Transportation Authority, with service to Pasquotank, Perquimans, Camden, Chowan, and Currituck counties.[64]

Elizabeth City has regularly scheduled inter-city bus service through Greyhound.

Rail

The Chesapeake and Albemarle Railroad, a short line operated by the North Carolina and Virginia Railroad, extends 82 miles (132 km) between Edenton, North Carolina, and Chesapeake, Virginia. This line had first been established in 1881 as the Elizabeth City and Norfolk Railroad, later renamed the Norfolk Southern Railway. Once one of Norfolk Southern's principal lines, the decline of the region's industry and the demolition of tracks across the Albemarle Sound from Edenton to Mackey's Ferry marginalized the route, forcing the line's lease to the Chesapeake and Albemarle in 1990.[65] The railroad still serves the region, primarily carrying grain, sand, gravel and other raw materials to and from the Norfolk Southern and CSX mainlines in Chesapeake.

Passenger service to Elizabeth City ended in 1947. Today, the closest passenger service is provided by Amtrak in Newport News, Virginia, approximately one hour to the north. Though an Amtrak station exists in Norfolk, Virginia, most outbound passengers from Norfolk are bussed via Amtrak Connect to Newport News instead.

Notable people

Academia

- Joseph C. Price (1854–1893), founder and first president of Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina[66]

- Lorenzo Dow Turner (1890–1972), an African-American academic and linguist who pioneered research on the Gullah language

Politics

- Herbert Harvell Bateman (1928–2000), Virginia State Senator (Newport News, VA) and U.S. Congressman (Virginia 1st Congressional District)

- Lee Jin Carter (born 1987), initially joined the US Marines as IT specialist and later became elected as a political delegate for Virginia's 50th House of Delegates district, well known for being a self-proclaimed socialist[67][68]

- John Warren Davis (1867–1945), federal judge and a New Jersey politician

- John C. B. Ehringhaus (1882–1949), was the first and only Elizabeth City citizen to serve as North Carolina governor from 1933 to 1937

- Gerald Lamb (1924–2014), Connecticut State Treasurer (1963–1970) and the first African American to be elected to that office in the US

Business

- James W. Owens (born 1946), former chairman and CEO of Caterpillar Inc. 2004-2010

Sports

- Luther "Wimpy" Lassiter (1918–1988), world-renowned nine-ball pool player

- Cecil Rouson (born 1962), former NFL running back for the New York Giants and the Cleveland Browns

- Sha'Keela Saunders (born 1993), track and field athlete who competes in the long jump[69]

- Anthony Smith (born 1967), former NFL defensive end[70]

- John Walton (born 1947), former NFL quarterback[71]

- Kenny Williams (born 1969), former professional basketball player, most notably with the NBA's Indiana Pacers

Entertainment

- Max Roach (1924–2007), nationally known jazz percussionist, drummer and composer. Roach was born in the northern Pasquotank County township of Newland north of Elizabeth City.

- Scott Sanders (born 1968), screenwriter and director known for Black Dynamite

Other

- Franklin D. Miller (1945–2000), United States Army staff sergeant during the Vietnam War and recipient of the Medal of Honor[72]

- Edward Snowden (born 1983), was revealed in June 2013 as an NSA whistleblower, leaking classified government documents to The Guardian newspaper of Britain[73][74]

See also

References

- ↑ "Harbor of Hospitality". USPTO. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ↑ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Elizabeth City, North Carolina

- 1 2 "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- 1 2 "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". Census.gov. US Census Bureau. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "City Data". City Data. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Elizabeth City, NC Micro Area; North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Elizabeth City website

- ↑ "historicelizabethcity.org". Archived from the original on August 2, 2012.

- ↑ "historicelizabethcity.org". Archived from the original on August 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Elizabeth City, One of America's Best Small Towns". Archived from the original on December 3, 2009. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- 1 2 "historicelizabethcity.org". Archived from the original on January 12, 2013.

- 1 2 "Elizabeth City Shipyard". Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- 1 2 "Splinter Fleet - Subchaser Facts and Specifications". Archived from the original on November 8, 2004.

- ↑ "Submarine Chaser Photo Index". Archived from the original on January 12, 2008.

- ↑ "US Army Quick-Supply Boats QS". Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ Holaday, Chris (1998). Professional Baseball in North Carolina: An Illustrated City-by-city History, 1901-1996. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786425532.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Elizabeth City city, North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ↑ Elizabeth City website

- ↑ "Elizabeth City, North Carolina Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)". Archived from the original on March 22, 2012.

- 1 2 "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Station: Elizabeth City, NC". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Station: Elizabeth City CGAS, NC". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ↑ "American FactFinder - Results". Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ↑ Elizabeth City website

- ↑ Bob Montgomery (December 10, 2005). "Departing EC mayor proud of city's growth". Daily Advance. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Eastern District of North Carolina". Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Congressman G.K. Butterfield : Town and City Websites". Archived from the original on March 20, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ↑ "United States Coast Guard Complex". Visit NC. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ "USCG Base Elizabeth City, NC". Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ "TCOM - Leader in Affordable Persistent Surveillance Solutions - Design, Manufacture of Tethered Aerostat Systems - For over 40 years, TCOM innovations have defined the industry, and our pioneering achievements continue to revolutionize the design, manufacture and deployment of LTA systems. With corporate headquarters in Columbia, MD and manufacturing and testing facilities in Elizabeth City, NC, TCOM is the world's only company solely devoted to the design, fabrication, installation and operation of persistent surveillance aerostat systems". Archived from the original on March 6, 2005.

- ↑ "U. S. Naval Air Station (LTA) Weeksville, North Carolina...............................................................................................................................................ICW-NET Elizabeth City NC". Archived from the original on March 23, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Shooting Out The Lights With Wimpy". CNN. October 16, 1967. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Classic Moth Boats - Classic Moth Boat Association". Archived from the original on May 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Classic Moth Boat Association". Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ↑ "Irish Potato Festival, NC Potato Festival | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- ↑ Winslow, Lisa. "Home". Archived from the original on June 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Albemarle Craftsmans Fair" (PDF). Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ "Juneteenth 2022". River City Community Development Corporation. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ↑ "An old friend comes to you in a new way | the Daily Advance". Archived from the original on February 8, 2010. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Daily Advance Sold to Cooke Communications". Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ↑ Saunders, Keith. The Independent Man. Edwards and Broughton; [S.I.] : Saunders Press, 1962, p. 1.

- ↑ "Home - Elizabeth City-Pasquotank Public Schools". www.ecpps.k12.nc.us. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "ECSU :: University Relations & Marketing". Archived from the original on April 27, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Elizabeth City State University, Elizabeth City NC". Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "ECSU :: Department of Pharmacy & Health Professions". Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ↑ "College of the Albemarle - Welcome to COA > Campus History > 1960?s". Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Sentara Albemarle Medical Center - Sentara Healthcare". Archived from the original on October 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Sentara Healthcare - Your Community Not-For-Profit Health Provider - Sentara Healthcare". Archived from the original on May 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Sentara Healthcare - Your Community Not-For-Profit Health Provider - Sentara Healthcare" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 17, 2013.

- ↑ Elizabeth City website

- ↑ "East Albemarle Reqional Library Directory". Archived from the original on November 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 "List of Power Stations" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 31, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ↑ "Amazon Wind Farm US East". Archived from the original on December 31, 2017.

- ↑ "The Norfolk & Carolina Telephone & Telegraph Companies". Archived from the original on June 14, 2013.

- ↑ "About ICPTA". Archived from the original on February 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Norfolk & Southern Railway Historical Society". Archived from the original on November 27, 2010.

- ↑ Noted Educator, Prohibitionist and Civil Rights Leader Joseph C. Price. ncdcr.gov. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Lee Carter". Facebook. Archived from the original on May 1, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Lee J. Carter". www.facebook.com. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ Sha'Keela Saunders | USA Track and Field. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ↑ Anthony Smith Stats. Pro-Football-Reference. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ↑ John Booker Walton Stats. Pro-Football-Reference. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ↑ SSG Franklin D. Miller. ARSOF History. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Edward Snowden: the whistleblower behind the NSA surveillance revelations". The Guardian. June 10, 2013. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013.

- ↑ "'I will be made to suffer for my actions': Self-identified source for NSA leaks comes forward". Archived from the original on June 13, 2013.