Ellen Glasgow | |

|---|---|

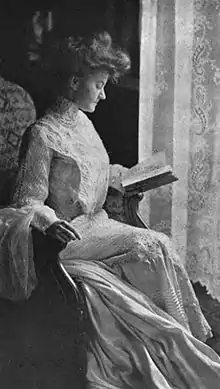

Portrait of Ellen Glasgow, by Aimé Dupont | |

| Born | Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow April 22, 1873 Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | November 21, 1945 (aged 72) Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Notable awards | Pulitzer Prize for the Novel (1942) |

| Signature | |

Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow (April 22, 1873 – November 21, 1945) was an American novelist who won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1942 for her novel In This Our Life.[1] She published 20 novels, as well as short stories, to critical acclaim. A lifelong Virginian, Glasgow portrayed the changing world of the contemporary South in a realistic manner, differing from the idealistic escapism that characterized Southern literature after Reconstruction.[2]

Early and family life

Born in Richmond, Virginia, on April 22, 1873, to Anne Jane Gholson (1831-1893) and her husband, Francis Thomas Glasgow, the young Glasgow developed differently from other women of her aristocratic class.[3] Due to poor health (later diagnosed as chronic heart disease), Glasgow was educated at home in Richmond, receiving the equivalent of a high school degree, although she read deeply in philosophy, social and political theory, as well as European and British literature.[4]

Her parents married on July 14, 1853, survived the American Civil War, and would have ten children together, of whom Ellen would be the next to youngest. Her mother, Anne Gholson, was inclined to what was then called "nervous invalidism"; which some attributed to her having borne and cared for ten children.[5] Glasgow also dealt with "nervous invalidism" throughout her life.[6] Ellen Glasgow thought her father self-righteous and unfeeling.[7] However, some of her more admirable characters reflect a Scots-Calvinist background like his and a similar "iron vein of Presbyterianism".[8]

.jpg.webp)

Ellen Glasgow spent many summers at her family's Louisa County, Virginia, estate, the historic Jerdone Castle plantation, which her father bought in 1879, and would later use that setting in her writings.[9]

Her paternal great-grandfather, Arthur Glasgow, had emigrated with his brothers in 1776 from Scotland to the then-large and frontier Augusta County, Virginia. Her father, Francis Thomas Glasgow, was raised in what had become Rockbridge County, Virginia, graduated from Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in 1847, and would eventually manage the Tredegar Iron Works.[10] Those had been bought in 1848 by Glasgow's maternal uncle, Joseph Reid Anderson, who had graduated fourth in his class of 49 from West Point in 1836 and would introduce the labor of skilled and enslaved Africans at the ironworks to accompany skilled white workers. Anderson was a major business and political figure in Richmond, who supported the Confederate States of America, joined the Army of Northern Virginia, and attained the rank of general.[11] However, because the Tredegar Ironworks produced munitions crucial to the Confederate cause, General Robert E. Lee asked General Anderson to return and manage the ironworks rather than lead armies in the field.[12]

Her mother was Anne Jane Gholson (1831-1893), born to William Yates Gholson and Martha Anne Jane Taylor at Needham plantation in Cumberland County, Virginia. Her grandparents were Congressman Thomas Gholson, Jr. and Anne Yates, who descended from Rev. William Yates, the College of William & Mary's fifth president (1761–1764).[13] Gholson was descended from William Randolph, a prominent colonist and land owner in the Commonwealth of Virginia. He and his wife, Mary Isham, were sometimes referred to as the "Adam and Eve" of Virginia.[13]

Career

During more than four decades of literary work, Glasgow published 20 novels, a collection of poems, a book of short stories, and a book of literary criticism. Her first novel, The Descendant (1897) was written in secret and published anonymously when she was 24 years old. She destroyed part of the manuscript after her mother died in 1893. Publication was further delayed because her brother-in-law and intellectual mentor, George McCormack, died the following year. Thus Glasgow completed her novel in 1895.[14] It features an emancipated heroine who seeks passion rather than marriage. Although it was published anonymously, her authorship became well known the following year, when her second novel, Phases of an Inferior Planet (1898), announced on its title page, "by Ellen Glasgow, author of The Descendant".

By the time The Descendant was in print, Glasgow had finished Phases of an Inferior Planet.[15] The novel portrays the demise of a marriage and focuses on "the spirituality of female friendship".[16] Critics found the story to be "sodden with hopelessness all the way though",[17] but "excellently told".[18] Glasgow stated that her third novel, The Voice of People (1900) was an objective view of the poor-white farmer in politics.[19] The hero is a young Southerner who, having a genius for politics, rises above the masses and falls in love with a higher class girl. Her next novel, The Battle-Ground (1902), sold over 21,000 copies in the first two weeks after publication.[20] It depicts the South before and during the Civil War and was hailed as "the first and best realistic treatment of the war from the southern point of view."[21]

.png.webp)

Much of her work was influenced by the romantic interests and human relationships that Glasgow developed throughout her life. The Deliverance (1904) and her previous novel, The Battle-Ground, were written during her affair with "Gerald B.", her long-time secret lover. They "are the only early books in which Glasgow's heroine and hero are united" by the novels' ends.[22] The Deliverance, published in 1904, was the first Glasgow book to garner popular success.[23] The novel portrays a romance built on the dramatic relationship between the hero and the heroine due to traditional class constraints. The hero is an aristocrat turned into a common laborer after the events of the Civil War, and the heroine lacks the aristocratic lineage but obtains aristocratic qualities such as education and refinement.[24] The genuine affection and reconciliation of the romance of the two were attempts by Glasgow to prove that "traditional class consciousness should be inconsequential to love affairs."[24] The Deliverance criticizes the institution of marriage because Glasgow herself faced social barriers that prevented her from marrying at that time. The Deliverance is notable for offering "a naturalistic treatment of class conflicts" that emerge after Reconstruction, providing realistic views of social changes in Southern literature.[2]

Glasgow's next four novels were written in what she considered her "earlier manner"[25] and received mixed reviews. The Wheel of Life (1906) sold moderately well based on the success of The Descendant. Despite its commercial success, however, reviewers found the book disappointing.[26] Set in New York (the only novel not set in Virginia), the story tells of domestic unhappiness and tangled love affairs.[27] It was unfavorably compared to Edith Wharton's House of Mirth, which was published that same year. Most critics recommended that Glasgow "stick to the South".[28] Glasgow regarded the novel as a failure.[29]

The Ancient Law (1908) portrayed white factory workers in the Virginia textile industry,[30] and analyzes the rise of industrial capitalism and its corresponding social ills.[31] Critics considered the book overly melodramatic.[32] With The Romance of a Plain Man (1909) and The Miller of Old Church (1911) Glasgow began concentrating on gender traditions; she contrasted the conventions of the Southern woman with the feminist viewpoint,[33] a direction which she continued in Virginia (1913).

As the United States women's suffrage movement was developing in the early 1900s, Glasgow marched in the English suffrage parades in the spring of 1909. Later she spoke at the first suffrage meeting in Virginia and was an early member of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia.[34][35] Glasgow felt that the movement came "at the wrong moment" for her, and her participation and interest waned.[36] Glasgow did not at first make women's roles her major theme, and she was slow to place heroines rather than heroes at the centers of her stories.[37] Some called her Virginia (1913; about a southern lady whose husband abandons her when he achieves success), Life and Gabriella (1916; about a woman abandoned by a weak-willed husband, but who becomes a self-sufficient, single mother who remarries well), and Barren Ground (1925); discussed below, her "women's trilogy". Her later works have heroines who display many of the attributes of women involved in the political movement.

Glasgow published two more novels, The Builders (1919) and One Man in His Time (1922), as well as a set of short stories (The Shadowy Third and Other Stories (1923)), before producing her novel of greatest personal importance, Barren Ground (1925).

Written in response to her waning romantic relationship with Henry W. Anderson, Barren Ground is a story that chronicles the life events of the main heroine.[38] Due to a troubled childhood, the heroine looks for escape in the form of companionship with the opposite sex. She meets a man and gets engaged, only for him to leave for New York and desert her. The heroine concludes that physical relationships with the opposite sex are meaningless and devotes herself to running her farm. Though she triumphs over the man who abandoned her, the victory is as bare and empty as the barren ground in the description of the introduction.[39] Glasgow wrote Barren Ground in retrospect to her own life, and the heroine's life mirrors hers almost exactly. Glasgow reverses the traditional seduction plot by producing a heroine completely freed from the southern patriarchal influence and pits women against their own biological natures.[2] Though she created an unnatural and melodramatic story that did not sell well with the public, it was hailed as a literary accomplishment by critics of the time. The imagery, descriptive power, and length of the book conveys the "unconquerable vastness" of the world. What endures in the novel is not the ideals of a cynical woman, but rather the landscape that is farmed by generations of humans who spend their brief time on earth on the land.[40] Glasgow portrays the insignificance of human relationships and romance by contrasting it directly to the vastness of nature itself.

By writing Barren Ground, a "tragedy", she believed that she freed herself for her comedies of manners The Romantic Comedians (1926), They Stooped to Folly (1929), and The Sheltered Life (1932). These late works are considered the most artful criticism of romantic illusion in her career.[41]

In 1923 a reviewer in Time characterized Glasgow:

She is of the South; but she is not by any manner of means provincial. She was educated, being a delicate child, at home and at private schools. Yet she is by no means a woman secluded from life. She has wide contacts and interests. ... Here is a really important figure in the history of American letters; for she has preserved for us the quality and the beauty of her real South.[42]

Artistic recognition of her work may have climaxed in 1931 when Glasgow presided over the Southern Writers Conference at the University of Virginia.[43]

Glasgow produced two more "novels of character",[44] The Sheltered Life (1932) and Vein of Iron (1935), in which she continued to explore female independence. The latter and Barren Ground of the previous decade remain in print.

In 1941 Glasgow published In This Our Life, the first of her writings to take a bold and progressive attitude towards black people.[45] Glasgow incorporated African Americans into the story as main characters of the narrative, and these characters become a theme within the novel itself. By portraying the blatant injustices that black people face in society, Glasgow provides a sense of realism in race relations that she had never done before.[45] Due to the ambiguity of the ending, the novel received a mixed and confused response from the public.[46] There is also a distinct discontinuity between critics of the time and the reading public, as the critics, notably her friends, hailed the novel as a "masterpiece", and the novel won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1942.[47] The novel was quickly bought by Warner Brothers and adapted as a movie by the same name, directed by John Huston and released in 1942.

Her autobiography, The Woman Within, published in 1954, years after her death, details her progression as an author and the influences essential for her becoming an acclaimed Southern woman writer. Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was gathering information for her commissioned biography of Ellen Glasgow prior to her death.[48]

Death and legacy

Glasgow died in her sleep at home on November 21, 1945,[49] and is buried in Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia. The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia maintains Glasgow's papers. Copies of Glasgow's correspondence may be found in the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings papers at the George A. Smathers Libraries Special Collections at the University of Florida. The Library of Virginia honored Glasgow in 2000 as she became a member of the inaugural class of Virginia Women in History.[50]

By basing her novels on her own life, Glasgow accurately portrayed the changing nature of Southern society. She was the founder of the realism movement in Southern literature that was previously made up by writers such as William Faulkner, who considered Reconstruction as "the greatest humiliation in Southern history."[51]

Personal life and relationships

Glasgow had several love interests during her life. In The Woman Within (1954), an autobiography written for posthumous publication, Glasgow tells of a long, secret affair with a married man she had met in New York City in 1900, whom she called Gerald B.[52] Ellen believed that he was the "one great love of her life", noting one particular visit with him in Switzerland:

A summer morning in the Alps. We were walking together over an emerald path. I remember the moss, the ferny greenness. I remember the Alpine blue of the sky. I remember, on my lips, the flushed air tasting like honey. The way was through a thick wood, in a park, and the path wound on and upward, higher and higher. We walked slowly, scarcely breathing in the brilliant light. On and upward, higher, and still higher. Then, suddenly, the trees parted, the woods thinned and disappeared. Earth and sky met and mingled. We stood, hand in hand, alone in the solitude, alone with the radiant whiteness of the Jungfrau. From the mountain we turned our eyes to each other. We were silent, because it seemed to us that all had been said. But the thought flashed through my mind, and was gone, "Never in all my life can I be happier than I am, now, here at this moment!"[53]

Since Gerald B.'s wife would not agree to a divorce, Ellen was unable to marry. In the end, nothing occurred but the short-lived meetings in New York and Switzerland; Glasgow wrote in her autobiography that Gerald B. died in 1905.[54]

Ellen also maintained a close lifelong friendship with James Branch Cabell, another notable Richmond writer. She was engaged twice but did not marry. In 1916, Glasgow met Henry W. Anderson, a prominent attorney and Republican Party leader, who collaborated with Glasgow and provided copies of his speeches for her novel The Builders.[55] He eventually became her fiance in 1917. However, the engagement occurred during the First World War, and Anderson, placed in charge of the Red Cross Commission in order to keep Romania on the side of the Allies, left for the country. There he met Queen Marie of Romania, and Anderson became infatuated with her. These developments, paired with a lack of communication between the two, strained the relationship between Glasgow and Anderson, and the planned marriage fell through.[56] Based on her experiences, Glasgow felt her best work was done when love was over.[57] By the end of her life, Glasgow lived with her secretary, Anne V. Bennett, 10 years her junior, at her home at 1 West Main Street in Richmond.[58]

Bibliography

| Library resources about Ellen Glasgow |

| By Ellen Glasgow |

|---|

Novels

- The Descendant (1897)

- Phases of an Inferior Planet (1898)

- The Voice of the People (1900)

- The Battle-Ground (1902)

- The Deliverance (1904)

- The Wheel of Life (1906)

- The Ancient Law (1908)[59]

- The Romance of a Plain Man (1909)

- The Miller of Old Church (1911)

- Virginia (1913)

- Life and Gabriella (1916)

- The Builders (1919)

- One Man in His Time (1922)

- Barren Ground (1925)

- The Romantic Comedians (1926)

- They Stooped to Folly (1929)

- The Sheltered Life (1932)

- Vein of Iron (1935)

- In This Our Life (1941) Pulitzer Prize for the Novel 1942, filmed in 1942 by John Huston with Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland.

Story Collections

- The Shadowy Third and Other Stories (1923)[60]

- The Collected Stories of Ellen Glasgow (1963) (12 stories, with an introduction by editor Richard Meeker)[61]

Verse

- The Freeman and Other Poems (1902)

Autobiography

- The Woman Within (published posthumously in 1954)[62]

Non-fiction

- A Certain Measure: An Interpretation of Prose Fiction (October 1943)

References

- Notes

- ↑ "Ellen Glasgow | American author | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Inge, Tonette Bond (1989). "Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow, 1873-1945". Charles Reagan Wilson & William R. Ferris, eds., Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. University of North Carolina Press.

- ↑ Inge, 883

- ↑ Heath

- ↑ Goodman, 19

- ↑ Domínguez-Rué, Emma (2011). Of lovely tyrants and invisible women the female invalid as metaphor in the fiction of Ellen Glasgow. Berlin. ISBN 978-3-8325-2813-3. OCLC 748702750.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Glasgow 12-3

- ↑ Glasgow 14

- ↑ Goodman, Susan (1998). Ellen Glasgow : a biography. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-8018-5728-7. OCLC 37579348.

- ↑ Glasgow, Ellen (1994). The woman within : an autobiography. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. p. 300. ISBN 0-8139-1563-5. OCLC 30739475.

- ↑ Bromberg, Alan B. "Anderson, Joseph R. (1813–1892)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ↑ Knight, Charles R. (2021). From Arlington to Appomattox : Robert E. Lee's Civil War, day by day, 1861-1865. El Dorado Hills. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-61121-503-8. OCLC 1257420359.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Roberts, Gary Boyd (2007). "Descendants of William Randolph and Henry Isham of Virginia". Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ↑ Publishers' Online, May 17, 2009

- ↑ Glasgow 129

- ↑ Matthews 33, 36

- ↑ Scura 21

- ↑ Scura 31

- ↑ Glasgow 181

- ↑ Goodman 89

- ↑ Raper 150

- ↑ Wagner 31

- ↑ Auchinloss 13

- 1 2 Godbold 64

- ↑ Raper 237

- ↑ Raper 227

- ↑ Scura 102

- ↑ Raper 228

- ↑ Wagner 37

- ↑ Raper 231

- ↑ Goodman 107

- ↑ Scura 129, Wagner 36

- ↑ Wagner 38

- ↑ Glasgow 185-6

- ↑ Graham, Sarah Hunter (April 1993). "Woman Suffrage in Virginia: The Equal Suffrage League and Pressure-Group Politics, 1909-1920". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 101: 230 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Glasgow 186

- ↑ Pannill 686

- ↑ Auchinloss 7

- ↑ Godbold 143

- ↑ Godbold 145

- ↑ Pannill

- ↑ Time. November 26 1923.

- ↑ Inge bio

- ↑ Wagner 119

- 1 2 Godbold 250

- ↑ Godbold 279

- ↑ Godbold 286

- ↑ Silverthorne, Elizabeth. Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings: Sojourner at Cross Creek. Woodstock, New York: Overlook Press. p. 3.

- ↑ Inge 884

- ↑ "Virginia Women in History". Lva.virginia.gov. June 30, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ↑ Holman 19

- ↑ Glasgow, 156

- ↑ Glasgow 164

- ↑ Godbold 62

- ↑ John T. Kneebone et al., eds., Dictionary of Virginia Biography (Richmond: The Library of Virginia, 1998- ), 1:136-137.

- ↑ Godbold 120

- ↑ Glasgow, 243-244

- ↑ 1940 U.S. Federal census for Richmond City.

- ↑ Buckingham, James Silk; Sterling, John; Maurice, Frederick Denison; Stebbing, Henry; Dilke, Charles Wentworth; Hervey, Thomas Kibble; Dixon, William Hepworth; MacColl, Norman; Rendall, Vernon Horace; Murry, John Middleton (March 28, 1908). "Review: The Ancient Law by Ellen Glasgow". The Athenaeum (4196): 380.

- ↑ Bleiler, Everett (1948). The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. Chicago: Shasta Publishers. p. 127.

- ↑ Meeker, Richard (1963). The Collected Stories of Ellen Glasgow. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- ↑ Yardley, Jonathan (November 29, 2003). "'Woman Within': An Unlikely Rebel of the Privileged South". The Washington Post.

- Bibliography

- Auchincloss, Louis. Ellen Glasgow. Vol. 33. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1964.

- Becker, Allen Wilkins. Ellen Glasgow: Her Novels and Their Place in the Development of Southern Fiction. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Master's Thesis, 1956.

- Cooper, Frederic Taber. Some American Story Tellers. New York: H. Holt and Company, 1911.

- Donovan, Josephine. After the fall the Demeter-Persephone Myth in Wharton, Cather, and Glasgow, University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1989.

- Glasgow, Ellen. "The Woman Within". University Press of Virginia, 1994.

- Godbold, Jr., E. Stanley. Ellen Glasgow and the Woman Within, 1972.

- Goodman, Susan. Ellen Glasgow: A Biography. Baltimore:Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

- Holman, C. Hugh. Three Modes of Modern Southern Fiction: Ellen Glasgow, William Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe. Vol. 9. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1966.

- Inge, M. Thomas, and Mary Baldwin College. Ellen Glasgow: Centennial Essays. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976.

- Inge, Tonette Bond. Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, ed. Charles Reagan Wilson and William R. Ferris. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

- Jessup, Josephine Lurie. The Faith of our Feminists. New York: R. R. Smith, 1950.

- Jones, Anne Goodwyn. Tomorrow Is Another Day: The Woman Writer in the South, 1859-1936, 1981.

- MacDonald, Edgar and Tonette Blond Inge. Ellen Glasgow: A Reference Guide (1897–1981), 1986.

- Mathews, Pamela R. Ellen Glasgow and a Woman's Traditions, 1994.

- McDowell, Frederick P. W. Ellen Glasgow and the Ironic Art of Fiction. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1960.

- Pannill, Linda in The Heath Anthology of American Literature, Vol. D. eds

- Patterson, Martha H. Beyond the Gibson Girl: Reimagining the American New Woman, 1895-1915. Urbana: U of Illinois Press, 2005.

- Publishers' Bindings Online. Accessed May 17, 2009

- Raper, Julius R. From the Sunken Garden: The Fiction of Ellen Glasgow, 1916-1945. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1980.

- Raper, Julius Rowan, and Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow. Without Shelter;the Early Career of Ellen Glasgow. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971.

- Reuben, Paul P. "Chapter 7: Ellen Glasgow". PAL: Perspectives in American Literature-A Research and Reference Guide. Accessed April 4, 2009.

- Richards, Marion K. Ellen Glasgow's Development as a Novelist. Vol. 24. The Hague: Mouton, 1971.

- Rouse, Blair. Ellen Glasgow. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1962.

- Rubin, Louis Decimus. No Place on Earth; Ellen Glasgow, James Branch Cabell, and Richmond-in-Virginia. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1959.

- Santas, Joan Foster. Ellen Glasgow's American Dream. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1965.

- Saunders, Catherine E. Writing the Margins: Edith Wharton, Ellen Glasgow, and the Literary Tradition of the Ruined Woman. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1987.

- Scura, Dorothy M. ed. Ellen Glasgow: The Contemporary Reviews. Knoxville: U of Tennessee Press, 1992.

- Thiebaux, Marcelle. Ellen Glasgow. NY: Ungar, 1982.

- Tutwiler, Carringon C., and University of Virginia Bibliographical Society. Ellen Glasgow's Library. Charlottesville, VA: Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, 1967.

- Time, November 26, 1923.

- Wagner, Linda W. Ellen Glasgow: Beyond Convention. Austin U of Texas Press, 1982.

Further reading

- Lang, Harry G.; Meath-Lang, Bonnie (1995). Deaf Persons in the Arts and Sciences: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313291708.

External links

- Ellen Glasgow at Library of Congress, with 18 library catalog records

- Works by Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Ellen Glasgow at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about Ellen Glasgow at Internet Archive

- Ellen Glasgow Society Archived October 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Photos of the first edition of In This Our Life

- Friends and Rivals: James Branch Cabell and Ellen Glasgow, Online exhibition, Virginia Commonwealth University

- "Ellen Glasgow". Encyclopedia.com.

- Ellen Glasgow letters to Bessie Judith Zaban Jones at the Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Special Collections

- Ellen Glasgow at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database