Enamelled glass or painted glass is glass which has been decorated with vitreous enamel (powdered glass, usually mixed with a binder) and then fired to fuse the glasses. It can produce brilliant and long-lasting colours, and be translucent or opaque. Unlike most methods of decorating glass, it allows painting using several colours, and along with glass engraving, has historically been the main technique used to create the full range of image types on glass.

All proper uses of the term "enamel" refer to glass made into some flexible form, put into place on an object in another material, and then melted by heat to fuse them with the object. It is called vitreous enamel or just "enamel" when used on metal surfaces, and "enamelled" overglaze decoration when on pottery, especially on porcelain. Here the supporting surface is glass. All three versions of the technique have been used to make brush-painted images, which on glass and pottery are the normal use of the technique.

Enamelled glass is only one of the techniques used in luxury glass, and at least until the Early Modern period it appears in each of the leading centres of this extravagant branch of the decorative arts, although it has tended to fall from fashion after two centuries or so. After a brief appearance in ancient Egypt, it was first made in any quantity in various Greco-Roman centres under the Roman Empire, then medieval Egypt and Syria, followed by medieval Venice, from where it spread across Europe, but especially to the Holy Roman Empire. After a decline from the mid-18th century, in the late 19th century it was revived in newer styles, led by French glassmakers. Enamel on metal remained a constant in goldsmithing and jewellery, and though enamelled glass seems to virtually disappear at some points, this perhaps helped the technique to revive quickly when a suitable environment arrived.

It has also been a technique used in stained glass windows, in most periods supplementary to other techniques, and has sometimes been used for portrait miniatures and other paintings on flat glass.

Techniques

Glass is enamelled by mixing powdered glass, either already coloured (more usual) or clear glass mixed with the pigments,[1] with a binder such as gum arabic that gives a thick liquid texture allowing it to be painted with brushes. Generally the desired colours only appear when the piece is fired, adding to the artist's difficulties. As with enamel on metal, gum tragacanth may be used to make sharp boundaries to the painted areas. The paint is applied to the vessel, which has already been fully formed; this is called the "blank" . Once painted, the enamelled glass vessel needs to be fired at a temperature high enough to melt the applied powder, but low enough that the vessel itself is only "softened" sufficiently to fuse the enamel with the glass surface, but not enough to deform or melt the original shape (unless this is desired, as it may be). The binding and demarcating substances burn away.[2]

Until recent centuries the enamel firing was done holding the vessel in a furnace on a pontil (long iron rod), with the glassmaker paying careful attention to any changes in the shape. Many pieces show two pontil marks on the base, where the pontil intruded on the glass, showing it had been on the furnace twice, before and after the enamels were applied. Modern techniques, in use since the 19th century, use enamels with a lower melting point, enabling the second firing to be done more conveniently in a kiln.[3]

.jpg.webp)

In fact some glassmakers allowed for a deforming effect in the second firing, which lowered and widened the shape of the vessel, sometimes very greatly, by making blanks that were taller and more narrow than the shape they actually wanted.[4] The enamels leave a layer of glass projecting very slightly over the original surface, the edges of which can be felt by running a finger over the surface. Enamelled glass is often used in combination with gilding, but lustreware, which often produces a "gold" metallic coating is a different process. Sometimes elements of the "blank", such as handles, may only be added after the enamel paints, during the second firing.[5]

Glass is sometimes "cold painted" with enamel paints that are not fired; often this was done on the underside of a bowl, to minimize wear on the painted surface. This was used for some elaborate Venetian pieces in the early 16th century, but the technique is "famously impermanent", and pieces have usually suffered badly from the paint falling off the glass.[6]

Some modern techniques are much simpler than historic ones.[7] For instance, there now exist glass enamel pens.[8] Mica may also be added for sparkle.[9]

History

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Ancient

The history of enamelled glass begins in ancient Egypt not long after the start of making glass vessels (as opposed to objects such as beads) around 1500 BC, and some 1400 years before the invention of glassblowing. A vase or jug, probably for perfumed oil, found in the tomb of the pharaoh Tutmose III and now in the British Museum dates to about 1425 BC. The base glass is blue, and it has geometrical decoration in yellow and white enamels; it is 8.7 cm high.[10] However, and rather "incredibly", this is the only known enamelled glass piece from before (about) the first century AD.[11]

Enamel was used to decorate glass vessels during the Roman period, and there is evidence of this as early as the late Republican and early Imperial periods in the Levant, Egypt, Britain and around the Black Sea.[12][13] Designs were either painted freehand or over the top of outline incisions, and the technique probably originated in metalworking.[12] Production is thought to have come to a peak in the Claudian period and persisted for some three hundred years,[12] though archaeological evidence for this technique is limited to some forty vessels or vessel fragments.[12]

Among a variety of pieces, many perhaps fall into two broad groups: tall, clear drinking glasses painted with scenes of sex (from mythology) or violence (hunting, gladiators), and then low bowls, some of coloured glass, painted with birds and flowers. This latter group appear to date to about 20–70 AD, and findspots are widely distributed across the empire, indeed many are found beyond its borders; they may have been made in north Italy or Syria.[14]

The largest group of survivals comes from the Begram Hoard, found in Afghanistan, a deposit of various luxury items in storerooms, probably dating to the 1st century AD, or perhaps later. In the past they have been dated to the 3rd century. The group has several goblets and other pieces with figures. It is thought these pieces were made in a Roman centre around the Mediterranean, perhaps Alexandria.[15]

.jpg.webp) Roman bowl with bird, found outside the empire, in modern Denmark

Roman bowl with bird, found outside the empire, in modern Denmark Goblet with Abduction of Europa, Begram Hoard

Goblet with Abduction of Europa, Begram Hoard Goblet with date harvesting, Begram Hoard

Goblet with date harvesting, Begram Hoard.jpg.webp)

Byzantine

After about the 3rd century Greco-Roman enamelled glass disappears, and there is another long gap in the history of the technique. This is ended in spectacular fashion by a 10th or 11th-century Byzantine bowl in the Treasury of Saint Mark's, Venice. This is of very high quality and shows great confidence in using the technique, which had no doubt been reborrowed from enamel on metal, although Byzantine enamel uses brush painting very little.[16] Some other, technically similar works, one possibly from the same workshop, are also extant.[17]

Islamic

.jpg.webp)

There is little surviving Byzantine enamelled glass, but enamel was much used for jewellery and religious objects, and appears again on glass in the Islamic Mamluk Empire from the 13th century onwards,[20] used for mosque lamps in particular, but also various types of bowls and drinking glasses. Gilding is often combined with enamels. The painted decoration was generally abstract, or inscriptions, but sometimes included figures. The places of manufacture are generally assumed to have been in Egypt or Syria, with any more precise locating tentative and somewhat controversial.[21] Enamels used oil-based medium and a brush or reed pen, and the physical properties of the medium encouraged inscriptions, which are useful for determining dates and authorship.[22]

According to Carl Johan Lamm, whose two-volume book on Islamic glass (Mittelalterliche Glaser und Steinschnittarbeiten aus dem Nahen Osten, Berlin, 1929/30) has long been the standard work, the main centres, each with its own style, were in turn Raqqa (1170–1270), Aleppo (13th century), Damascus (1250–1310) and Fustat (Cairo, 1270–1340). However this chronology has been disputed in recent years, tending to push dates later, and rearranging the locations. In particular there is disagreement as to whether elaborate pieces with figural decoration are early or late, effectively 13th or 14th century, with Rachel Ward arguing for the later dates.[23]

The shape of mosque lamps in this period is very standard; despite being suspended in the air through their lugs when in use, they have a broad foot, a rounded central body, and a wide flaring mouth. Filled with oil, they lit not only mosques, but also similar spaces such as madrassas and mausoleums. Mosque lamps typically have the Quranic verse of light written on them, and very frequently record the name and title of the donor, an important thing as far as he was concerned, as well as the name of the reigning sultan; they are thus easy to date reasonably precisely. As Muslim rulers came to have quasi-heraldic blazons, these are often painted.[24]

Enamelled glass became more rare, and of rather poorer quality, in the 15th century. This decline may have been partly due to the sack of Damascus by Tamerlane in 1401, as has often been claimed, though by then Cairo was the main centre.[25]

Some secular vessels have painted decoration including figures; some of this may have been intended for non-Islamic export markets, or Christian customers, which is clearly the case with a few pieces, including a bottle elaborately painted with clearly Christian scenes that may commemorate the election for a new abbot at a Syrian monastery.[26] Other pieces show the courtly scenes of princes, riders hawking or fighting, that is found in other media in contemporary Islamic art, and sometimes inscriptions make it clear these were intended for Muslim patrons.[27]

After mosque lamps, the most common shape is a tall beaker, flaring towards the top. This was made somewhat differently from the mosque lamps, the flaring apparently done in the course of the second firing.[28] These often have figural decoration, although the Luck of Edenhall, perhaps the finest of the group, does not. Some have decoration of fishes or birds,[29] and other humans, often on horseback.[30] The Palmer Cup in the Waddesdon Bequest (British Museum) shows an enthroned ruler flanked by attendants,[31] a scene often found in overglaze enamels on Persian pottery mina'i ware in the decades around 1200.[32] Two beakers in Baltimore (one illustrated below), have Christian scenes.[33]

Beaker with polo-players, 1250–1300

Beaker with polo-players, 1250–1300.jpg.webp)

13th-century bottle, Syria, likely used for perfume

13th-century bottle, Syria, likely used for perfume Egyptian mosque lamp, 14th century

Egyptian mosque lamp, 14th century.jpg.webp) Bucket, Syria, 14th century

Bucket, Syria, 14th century 14th-century plate

14th-century plate

Western Europe

.jpg.webp)

It is now known that the technique was being used in Venetian glass from the late 13th century, mostly to make beakers.[34] Until about 1970 it was thought it did not appear in Venice until around 1460,[35] and surviving early Venetian pieces were attributed elsewhere. The Aldrevandin(i) Beaker in the British Museum is now regarded as a work of about 1330, having once been thought to be much later. It is an armorial beaker that is, unusually, inscribed with the name of its maker: "“magister aldrevandin me feci(t)” – probably the decorator.[36] It is "the iconic head of a group of more or less similar objects" and arguably "the most widely known and published medieval European glass vessel". It is large and "has considerable visual “gravity.” When it is held, however, it is shockingly lightweight" with in most parts, the glass sides "scarcely more than a millimeter thick".[37]

Angelo Barovier's workshop was the most important in Venice in the mid-15th century – in the past his family was credited with introducing the technique. Much Venetian glass was exported, especially to the Holy Roman Empire, and copied increasingly expertly by local makers, especially in Germany and Bohemia.[38] By the 16th century the place of manufacture of pieces described as "facon de Venise" ("Venetian style") is often hard to discern.

Armorial glass, with a painted coat of arms or other heraldic insignia, was extremely popular with the wealthy. The painting was often not done at the same time or place as the main vessel was made; it might even be in a different country. This remains an aspect of enamelled glass; by the 19th century some British-made glass was even being sent to India to be painted. The Reichsadlerhumpen or "Imperial Eagle beaker" was a large beaker, holding as much as three litres, presumably for beer, showing the double-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire, with the arms of the imperial various territories on its wings. This was a popular showpiece that did not need customised designs. It was probably first made in Venice, but was soon mainly made in Germany and Bohemia.[39]

By the 17th century, "German enamelling became stereotyped within a limited range of subjects", most often using the humpen beaker shape.[35] The earliest dated enamelled humpen is from 1571, in the British Museum;[40] a late example, dated 1743, is illustrated above. Another standard design was the Kurfürstenhumpen or "Elector's beaker", showing the Electors of the Holy Roman Emperor, often in procession on horseback, in two registers, or alternatively seated around the emperor. Drinking glasses with royal arms are often called hofkellereihumpen (court cellar beaker). Other subjects are seen, including religious ones such as the Apostelhumpen, with the twelve apostles, hunting scenes, standard groups of personifications such as the Four Seasons, Ages of Man and the like, and pairs of lovers.[41] In Renaissance Venice, "betrothal" pieces were made to celebrate engagements or weddings, with the coats of arms or idealized portraits of the couple.[42]

Enamelled glass ceased to be fashionable in Italy by around 1550, but the broadly Venetian style remained popular in Germany and Bohemia until the mid-18th century, after which the remaining production was of much lower quality, though often bright and cheerful in a folk art way. It is sometimes called "peasant glass", though neither the makers nor customers fitted that description.[43] Enamelled glass was now relatively cheap, and the more basic styles were no longer a luxury preserve of the rich. By this time a new style using opaque white milk glass had become popular in Italy, England and elsewhere. The glass was hard to distinguish visually from porcelain, but much cheaper to make, and the enamel painting technique was very similar to the overglaze enamel painting by then the standard for expensive porcelain. The English makers specialized in small vases, typically up to seven inches tall, usually with a couple of chinoiserie figures; London, Bristol and south Staffordshire were centres.[44] Even smaller perfume or snuff bottles with stoppers were also being made in China itself, where they represented a cheaper alternative to materials such as jade.[45]

A distinct style that originated with the glassmaker Johann Schaper of Nuremberg in Germany around 1650 was the schwarzlot style, using only black enamel on clear or sometimes white milk glass. This was a relatively linear style, with images often drawing on contemporary printmaking. Schaper himself was the best artist to use it, specializing in landscapes and architectural subjects. The style was practiced in Germany and Bohemia until about 1750, and indeed is sometimes used on a large scale on German windows much later.[46]

In the 19th century there was increasing technical quality in many parts of Europe, initially with revivalist or over-elaborate Victorian styles; the Prague firm of Moser was a leading producer. In the later part of the century fresher and more innovative designs, often anticipating Art Nouveau, were led by French makers such as Daum and Émile Gallé.[47] It was for the first time possible to kiln-fire pieces, greatly simplifying the process and making it more reliable, reducing the risk of having to reject pieces and so allowing more investment in elaborate decorative work.[48]

Most pieces were now relatively large vases or bowls for display; the style related to design movements in other media such as art pottery, the Arts and Crafts movement, but was often especially well suited to glass. This style, culminating in Art Nouveau glass, was normally extremely well made, and often used a variety of techniques, including enamel. The best known American firm, making Tiffany glass, was not especially associated with the use of enamel, but it frequently appears, often as a minor element in designs.[49]

On flat glass

Enamelled glass is mostly associated with glass vessels, but the same technique has often been used on flat glass. It has often been used as a supplementary technique in stained glass windows, to provide black linear detail, and colours for areas where great detail and a number of colours are required, such as the coats of arms of donors. Some windows were also painted in grisaille. The black material is usually called "glass paint" or "grisaille paint". It was powdered glass mixed with iron filings for colour and binders, which was applied to glass pieces before the window was made up, and then fired.[50] It therefore is essentially a form of enamel, but is not usually so called when talking about stained glass, where "enamel" refers to other colours, often applied over the whole surface of one of the many pieces making up a design .

Enamel on metal was used for portrait miniatures in 16th-century France, and enjoyed something of a revival after about 1750. Some artists, including Henry Bone, sometimes painted in enamels on glass rather than the usual copper plate, without the change in base material making much difference to their style. Jean-Étienne Liotard, who usually worked in pastel, made at least one genre painting in enamels on glass.[51]

Gallery

Aldrevandini beaker, a Venetian glass with enamel decoration derived from Islamic technique and style. c. 1330.[36]

Aldrevandini beaker, a Venetian glass with enamel decoration derived from Islamic technique and style. c. 1330.[36] Goblet, Venice, 1475–1510

Goblet, Venice, 1475–1510_LACMA_48.24.214a-b.jpg.webp) German Apostelhumpen, 1600–50

German Apostelhumpen, 1600–50_LACMA_M.76.2.13_(cropped).jpg.webp) Base for a Water Pipe (huqqa), Lucknow, India, 1700–1750

Base for a Water Pipe (huqqa), Lucknow, India, 1700–1750.jpg.webp) Bohemian mug, 18th century, typical of so-called "peasant glass"

Bohemian mug, 18th century, typical of so-called "peasant glass".jpg.webp) English vase with chinoiserie shape and decoration, 5 inches tall, 1755–65, probably Bristol

English vase with chinoiserie shape and decoration, 5 inches tall, 1755–65, probably Bristol.jpg.webp) Chinese snuff bottle, 18th-century, 3 inches high

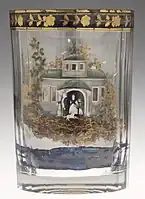

Chinese snuff bottle, 18th-century, 3 inches high Novelty Russian tumbler; the glass has two layers, and the gap has the landscape image built up with moss, straw, paper, sand, stone, clay and mica, as well as painted enamel, 1800–10

Novelty Russian tumbler; the glass has two layers, and the gap has the landscape image built up with moss, straw, paper, sand, stone, clay and mica, as well as painted enamel, 1800–10 Italian goblet, 19th century

Italian goblet, 19th century

%252C_late_19th_century_(CH_18470945)_(cropped).jpg.webp) Daum vase with forest scene, French, late 19th century

Daum vase with forest scene, French, late 19th century Vase Herbes et Papillons ("Grass and Butterflies"), Émile Gallé, c. 1879

Vase Herbes et Papillons ("Grass and Butterflies"), Émile Gallé, c. 1879 Japanese enamel made using the musen shippō (無線七宝) technique; wire is used to locate the glass, but then removed before firing.

Japanese enamel made using the musen shippō (無線七宝) technique; wire is used to locate the glass, but then removed before firing.

Notes

- ↑ Gudenrath, 23–24

- ↑ Ward, 57–59; Carboni, 203; Gudenrath, 23–27, and throughout, has very full details of manufacturing processes.

- ↑ Gudenrath, 23–27, and throughout, has very full details of manufacturing processes. Gudenrath is emphatic that kiln firing of enamels is not found before the 19th century, and criticises Carboni and many others for propagating this "misunderstanding" – see 69–70.

- ↑ Gudenrath, 50–58

- ↑ Gudenrath, 35–36, 52

- ↑ Gudenrath, 23

- ↑ "All About Glass – Corning Museum of Glass". www.cmog.org. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ↑ Enameling ebook Archived 2020-08-04 at the Wayback Machine, Delphi Glass

- ↑ "How to Enamel". glass-fusing-made-easy.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ↑ Gudenrath, 28

- ↑ Gudenrath, 30; British Museum page Archived 2020-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 Rutti, B., Early Enamelled Glass, in Roman Glass: two centuries of art and invention, M. Newby and K. Painter, Editors. 1991, Society of Antiquaries of London: London.

- ↑ So Rutti; Gudenrath, 33 has Roman examples "beginning in the early decades of the empire".

- ↑ Gudenrath, 33

- ↑ Whitehouse, 441–445, these are his "Group 10".

- ↑ Gudenrath, 40–42; also Gudenrath, William, et al. “Notes on the Byzantine Painted Bowl in the Treasury of San Marco, Venice.” Journal of Glass Studies, vol. 49, 2007, pp. 57–62. JSTOR Archived 2020-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "The Treasury of San Marco, Venice". www.metmuseum.org. MET Museum. 1984. Section on pages 180–183 (including illustrations)

- ↑ "Mosque Lamp of Amir Qawsun" Archived 2020-06-02 at the Wayback Machine, Metropolitan Museum

- ↑ Carboni, 254–256; the whole bottle

- ↑ Osborne, 335, though individual dates, especially of pieces with figural decoration, have been controversial in recent years – see Ward, 55–57

- ↑ Carboni, 199–207, and entries following; Ward, 55; Gudenrath, 42

- ↑ Carboni, Stefano. "Enameled and Gilded Glass from Islamic Lands". www.metmuseum.org. Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Ward, 55–57; Carboni, 204

- ↑ Ward, 57; Carboni, 203, 207; Doha, Museum of Islamic Art. "Mosque Lamp". www.mia.org.qa. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ↑ Carboni, 207; Ward, 70–71

- ↑ Carboni, 242–245 (# 121). He is aware only of this bottle and the two beakers in Baltimore, mentioned below.

- ↑ Carboni, 226–227, 241–242, 247–252

- ↑ Gudenrath, 43–46

- ↑ Fish; birds

- ↑ Example in Louvre, and Freer Sackler

- ↑ Contadini, Anna (1998), "Poetry on Enamelled Glass: The Palmer Cup in the British Museum", in: Ward, R, (ed.), Gilded and Enamelled Glass from the Middle East. London: British Museum Press, pp. 56–60.; "Palmer Cup", Waddesdon Bequest Archived 2020-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, "Palmer Cup" Archived 2020-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, British Museum; Carboni, 242; it has been given a metal mount in France, turning it into a goblet.

- ↑ Carboni, 205

- 1 2 Carboni, 244

- ↑ "Aldrevandini Beaker, British Museum". Archived from the original on 2020-06-25. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- 1 2 Osborne, 335

- 1 2 Gudenrath, 47–50; Aldrevandini beaker Archived 2020-06-26 at the Wayback Machine, British Museum

- ↑ Gudenrath, 48

- ↑ Gudenrath, 62–63

- ↑ Osborne, 335; Gudenrath, 62–65

- ↑ Gudenrath, 62

- ↑ Osborne, 335, 401

- ↑ "Venetian betrothal goblet, Victoria and Albert Museum". Archived from the original on 2020-06-10. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- ↑ Osborne, 335; Gudenrath, 64–65

- ↑ Gudenrath, 65–66; Osborne, 401

- ↑ Osborne, 335–336

- ↑ Osborne, 335–336, 693–694; Gudenrath, 64

- ↑ Osborne, 336, 401–403

- ↑ Gudenrath, 66–68

- ↑ "Objects of Beauty- Art Nouveau glass and jewellery". Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ↑ Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Materials, Methods, and Expressions, xvii, eds., Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz, Elizabeth Pastan, 2019, BRILL, ISBN 9004395717, 9789004395718, google books Archived 2022-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Swoboda, Gudrun, "Point of View #2: Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789), Painter of Extremes", 7–10, 14, in KHM Ansichtssache #2, Vienna, online Archived 2020-06-28 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Carboni, Stephen, and others, Glass of the Sultans: Twelve Centuries of Masterworks from the Islamic World, Corning Museum of Glass / Metropolitan Museum of Art / Yale UP, 2001, ISBN 0870999877 ISBN 9780870999871, online

- Gudenrath, William, "Enameled Glass Vessels, 1425 BCE – 1800: The Decorating Process", Journal of Glass Studies, vol. 48, pp. 23–70, 2006, JSTOR, Online at the Corning Museum of Glass (no page numbers)

- Osborne, Harold (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, 1975, OUP, ISBN 0198661134

- Ward, Rachel, "Mosque lamps and enamelled glass: Getting the dates right", in The Arts of the Mamluks in Egypt and Syria: Evolution and Impact, ed. Doris Behrens-Abouseif, 2012, V&R unipress GmbH, ISBN 3899719158, 9783899719154, google books

- Whitehouse, David, "Begram: The Glass", Topoi' Orient-Occident, 2001 11-1, pp. 437–449, online

.jpg.webp)