An increasing number of refugees and migrants have been entering the United Kingdom illegally by crossing the English Channel in the last decades. The Strait of Dover section between Dover in England and Calais in France represents the shortest sea crossing, and is a long-established shipping route. The shortest distance across the strait, at approximately 20 miles (32 kilometres), is from the South Foreland, northeast of Dover in the English county of Kent, to Cap Gris Nez, a cape near to Calais in the French département of Pas-de-Calais.[1]

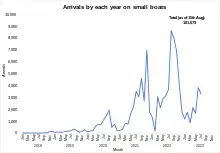

As of 1 November 2023, the Home Office has detected 111,588 migrants who have crossed the English Channel in small boats since 2018.[2][3]

Background

Seaborne crossings aboard small boats by would-be refugees and migrants were rare before 2018, however some crossings were recorded in the summer of 2016 during the European migrant crisis.[4][5][6][7] More commonly, migrants stowed away aboard trains, lorries or ferry boats, a technique that has become more difficult in recent years as British authorities have intensified searches of such vehicles and funded the construction of border fences in France.[8][6][9] Prices charged by smugglers for illegal rides across the Channel in lorries, trains and ferries have risen sharply.[9] Rumours that entering and claiming asylum in the UK would become more difficult once Brexit goes into effect circulated in migrant encampments in France, possibly fomented by people smugglers hoping to drum up business.[10][6][9]

If migrants arrive in England through illegal means, upon arrival the UK Government is unlikely to reject their claims to asylum. In 2019 at least 1,890 migrants arrived from France via small boats; the Home Office reported that only around 125 were returned to other European countries.[11]

Since November 2018, the number of migrants crossing has grown. The total number of migrants arriving by this route during 2018 was 297.[12] In 2019 and 2020 the numbers grew significantly, and by September 2020 an estimated total of 7,500 had entered Britain by this route. Many arrive in small boats, ferries and may enter the country unnoticed, whilst others are apprehended on landing or are rescued when their craft founders off shore.

Until the dispersal of the Calais Jungle in 2016, which contained an estimated 3,000 would-be immigrants to the UK, the majority of asylum seekers entering the country via the English Channel did so through the Channel Tunnel, mostly by hiding in vehicles.

With the increase in numbers crossing the channel in 2019, anti-immigration politicians attached the label "crisis" to the sudden increase in seaborne crossings.[6] Former Home Secretary Sajid Javid preferred to describe the increase in crossings as a "major incident."[13][14] Journalist and former Scottish Labour Party MP Tom Harris argued that the small boat crossings that are occurring are not a "crisis."[15]

Timeline

2018

The first migrants to have been recorded landing in the UK by small boat as recorded by the government was on 31 January 2018 when seven people crossed in a single boat.[16]

539 refugees and migrants are documented to have "tried to reach Britain on small boats" in 2018; many, however, were intercepted and returned to France.[17] 434 migrants are known to have made the crossing in small boats in October, November and December 2018,[18] 100 in November 2018,[10] 230 in December.[18][19]

Following the surge in migrant crossing incidents in November and December, on 28 December 2018 the UK Home secretary declared a major incident regarding refugees attempting to cross the channel.[14]

227 refugees and migrants were intercepted and returned to the continent by French authorities in 2018, "at least" 95 refugees and migrants in December alone.[13][18]

By way of comparison, 26,547 asylum claims were filed by would be refugees in the UK in 2017.[18]

2019

During the course of 2019, almost 1,900 had made the crossing by the end of the year.[20] From July to December 2019, an average of approximately 200 people made the crossing per month.[21]

2020

In April 2020, boat arrivals for that month was over 400 – the highest monthly total ever recorded.[21]

In July, the number of people crossing almost matched the combined total of May and June, with more migrants encouraged by good weather and calm seas.[22]

In August, it was reported that in 2020 so far almost 4,000 people had crossed the Channel illegally, using at least 300 small boats. On 6 August a record number of migrants arrived, at least 235.[23] It has also been observed that while it was originally mostly men that were arriving, young children and pregnant women and babies are now often among those arriving.[24]

The total number of migrants recorded to have crossed into the UK so far in 2020 was 3,948 as of 7 August.[25]

According to analysis by PA Media, the number of migrants reaching the UK shore has gone beyond 4,100 people in 2020. The Home Office confirmed that 151 migrants came ashore on 8 August. French authorities claimed that in the first six months of 2020, the number of migrants crossing the English Channel increased by five times, as compared to the last year.[26]

On 19 August a Sudanese boy, Abdulfatah Hamdallah, drowned in the Channel making the journey from France. He died after his and his friend's inflatable dinghy, which they were powering using shovels as oars, capsized. While his companion and British news media claimed he was 16 years old,[27][28] Boulogne-Sur-Mer's deputy public prosecutor Philippe Sabatier said a travel document provided by Mr Hamdallah gave his age as 28. The pair had previously been living in the Calais Jungle for at least two months prior.[29]

By 20 October, the total number of crossings in 2020 reached 7,294.[30]

On 27 October, a Kurdish-Iranian family of five from Sardasht died after a boat capsized outside France on way to reach the UK.[31][32] Artin Irannezhad, a 15 month old toddler from the shipwreck, washed up on Karmøy island on 1 January 2021.[33][34]

By the end of the year, about 635 boats had crossed the Channel, carrying 8,438 people.[35]

2021

Illegal crossings continued in 2021, including 103 people on 10 January and 77 people on 24 February.[35]

On 19 July 430 people crossed the channel, making it the largest crossing on record. 1,850 people had crossed in July alone, which is more than the total for the whole of 2019.[36]

On 11 November, a new record daily number of migrant crossings occurred, with around 1,000 people intercepted by border patrols. The cumulative total of 23,000 for the year was reported as far higher than previous years.[37]

On 24 November, the deadliest incident on record occurred. An inflatable dinghy carrying 30 migrants capsized while attempting to reach the UK, resulting in 27 deaths and one person missing. The victims included a pregnant woman and three children.[38]

2022

On one day in January, 271 migrants crossed the Channel.[39]

In March 2022, More than 3,000 people arrived in small boats, compared to 831 in March 2021, with 4,559 making the crossing so far this year.[40]

In the first week of August 1,886 people crossed the Channel.[41]

On 14 August, government figures showed that 20,000 people had crossed the channel in small boats since the start of the year. They stated 60,000 were expected to make the crossing in 2022.[42]

On 22 August, a total of 1,295 migrants crossed the Channel in 27 boats, setting a new record for crossings in a single day.[43]

As at 30 October, the total for the year of 2022 stood at 39,430.[44]

2023

The Home Office has predicted that the number of people arriving on small boats could reach 85,000 for the whole of 2023.[45] In the first three months of the year, 675 Indians arrived by small boats becoming the second most common nationality after Afghans (909). The number of Albanians arriving by small boats fell to 29.[46]

On 12 August, an overloaded boat sank resulting in the death of six people, all believed to be Afghan men in their 30s.[47]

In the first eight months of the year, just over 20,000 migrants have arrived using small boats. This figure is 20% fewer than at the same point of time in 2022, with the month of August seeing a 38% reduction in crossings compared to 2022 (8,631 migrants in 2022 compared to 5,369 in 2023).[48] By the middle of November 2023, the number of people arriving by small boat crossings has continued to fall with a 33% reduction recorded compared to the same point of time last year.[49] The Immigration Minister Robert Jenrick has stated the fall in numbers was achieved in spite of better weather conditions and a significant rise in irregular arrivals across Europe, with the number of people crossing the Mediterranean to Italy more than doubling compared to the previous year.[50]

Overall, 2023 saw a 36% fall in crossings compared to 2022, however the Immigration Services Union described the fall as a "glitch" with "higher numbers" expected for 2024.[51]

2024

On 14 January, five migrants trying to cross the channel were found dead in a beach off of northern France.[52]

Statistics

Total number of crossings

| Year | Arrivals (% change from prior year) |

|---|---|

| 2018 | 299 |

| 2019 | 1,843(+516.4%) |

| 2020 | 8,466(+359.3%) |

| 2021 | 28,526(+236.9%) |

| 2022 | 45,755(+60.4%) |

| 2023 | 29,437(-35.6%) |

By age and sex

The below charts are demographic breakdowns, as recorded by the Home Office, of the age and sex of small boat arrivals from January 2018 to December 2022.[53] 72,324 of small boat arrivals between 2018–2022 were male, 9,527 were female with 3,038 recorded as unknown. 63,101 of arrivals were between the ages of 18 and 39 representing the majority (74.3%) of those arriving.[53]

Small Boat Arrivals by Sex from 2018—2022.

Small Boat Arrivals by Age Group from 2018—2022.

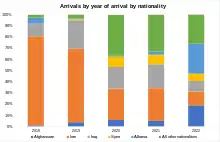

Countries of origin

In the first 10 months of 2023, there has been a change in the countries of origin of small boat arrivals. A 90% reduction in the number of Albanians crossing the Channel has been quoted by some government ministers,[54] with 947 Albanians recorded for the year until October. The top 10 nationalities for the year to date are recorded below:[55][56][57]

| Rank | Nationality | Small Boat Arrivals | Percent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,317 | 19.9% | |

| 2 | 2,962 | 11.0% | |

| 3 | 2,869 | 10.7% | |

| 4 | 2,629 | 9.8% | |

| 5 | 2,333 | 8.7% | |

| 6 | 1,976 | 7.4% | |

| 7 | 1,657 | 6.2% | |

| 8 | 1,303 | 4.9% | |

| 9 | 1,182 | 4.4% | |

| 10 | 947 | 3.5% | |

| All other nationalities | 3,524 | 13.2% | |

| Total (Jan to Oct 2023) | 26,699 | 100% | |

The top 10 nationalities by small boat arrivals to the United Kingdom, as recorded by the Home Office, are listed below for January to December 2022 and for aggregated figures from January 2018 to December 2022.[2] Albanians represented the most significant increase in small boat arrivals, from 16 arrivals in 2018 to 12,301 arrivals in 2022,[2] of whom 95% are male.[58]

| Rank | Nationality | Small Boat Arrivals | Percent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12,301 | 26.9% | |

| 2 | 8,633 | 18.9% | |

| 3 | 5,642 | 12.3% | |

| 4 | 4,377 | 9.6% | |

| 5 | 2,916 | 6.4% | |

| 6 | 1,942 | 4.2% | |

| 7 | 1,704 | 3.7% | |

| 8 | 1,160 | 2.5% | |

| 9 | 1,076 | 2.4% | |

| 10 | 683 | 1.5% | |

| All other nationalities | 3,360 | 7.3% | |

| Not currently recorded | 1,961 | 4.3% | |

| Total (2022) | 45,755 | 100% | |

| Rank | Nationality | Small Boat Arrivals | Percent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17,785 | 21.0% | |

| 2 | 13,199 | 15.6% | |

| 3 | 12,646 | 14.9% | |

| 4 | 10,636 | 12.5% | |

| 5 | 6,158 | 7.3% | |

| 6 | 5,328 | 6.3% | |

| 7 | 3,737 | 4.4% | |

| 8 | 2,005 | 2.4% | |

| 9 | 1,580 | 1.9% | |

| 10 | 1,171 | 1.4% | |

| All other nationalities | 8,101 | 9.5% | |

| Not currently recorded | 2,543 | 3.0% | |

| Total (2018—22) | 84,889 | 100% | |

In early 2019, it was reported that many of the people making the small boat crossings were from Iran.[9][59][60] In the first half of 2022, Albanians made up 18% of recorded arrivals, Afghans 18% and Iranians 15%.[61] In August 2022, it was reported that British government officials believed that Albanians now made up 50 to 60% of small boat migrant arrivals, with 1,727 Albanian arrivals recorded in May and June 2022 compared to only 898 between 2018 and 2021.[62]

Smuggling gangs

Crossings are usually arranged by smugglers who charge between £3,000 and £6,000 for a crossing attempt in a small boat.[10][59] The smugglers often use stolen boats for the crossings.[59][63][64][65]

On 2 January 2019 the National Crime Agency announced the arrest of a 33-year-old Iranian and a 24-year-old Briton in Manchester on suspicion of arranging the "illegal movement of migrants" across the English Channel.[66]

Deaths

| Year | Drowning deaths |

|---|---|

| 2018 | 1 |

| 2019 | 5 |

| 2020 | 9 |

| 2021 | 37 |

| 2022 | 5 |

| 2023 | 12 |

| Total | 69 |

According to the International Organization for Migration, 69 migrants have drowned in the English Channel trying to reach the UK between 2018 and 2023.[67]

November 2021 English Channel disaster

On 24 November 2021, 27 migrants drowned whilst trying to cross the English Channel from France to the United Kingdom in an inflatable dinghy. PM Boris Johnson called an emergency COBRA meeting in order to discuss the issue.[68]

December 2022 English Channel incident

On 14 December 2022, four migrants died and more than 40 were rescued after a small boat began sinking in ice-cold waters off the coast of Dungeness in the middle of the night.[69]

August 2023 English Channel incident

On 12 August, an overloaded boat sank resulting in the death of six people, all believed to be Afghan men in their 30s.[47]

Responses

Government response

In December 2018 Home Secretary Sajid Javid cut short a family holiday to deal with the small boat crossings.[13][14][70] On 31 December 2018 Javid reversed a previous refusal to station additional Border Force cutters in the Channel to intercept migrant small craft on the grounds that the cutters would become a "magnet" for migrants to attempt the crossing in the hope that their boats would be intercepted and enabled to apply for asylum. In agreeing to send more patrol boats, Javid promised to do "everything we can" to make sure that small boat migration "is not a success", including returning would-be migrants to France.[70] Cutters were reassigned from Gibraltar and the Mediterranean to carry out the channel mission.[70]

Javid has stated that migrants crossing the Channel from France or Belgium are not "genuine" asylum seekers, since they are already residing in a safe country.[71]

In response to the increase in arrivals due to calm seas in July and August 2020,[22] Javid's successor as Home Secretary, Priti Patel, was reportedly "furious" and responded by saying she planned to make the English Channel an "unviable" route into the UK. She sought military assistance from the Royal Navy to prevent migrant vessels from leaving France.[24][72]

On 10 August 2020, then Prime Minister Boris Johnson made a statement:

There's no doubt that it would be helpful if we could work with our French friends to stop them getting over the Channel. Be in no doubt, what's going on is the activity of cruel and criminal gangs who are risking the lives of these people taking them across the Channel, a pretty dangerous stretch of water, in potentially unseaworthy vessels. We want to stop that, working with the French, make sure that they understand that this isn't a good idea, this is a very bad and stupid and dangerous and criminal thing to do. But then there's a second thing we've got to do, and that is to look at the legal framework that we have that means that when people do get here, it is very, very difficult to then send them away again, even though blatantly they've come here illegally.[73][74]

On 7 September 2020, the UK government deployed the Thales Watchkeeper WK450, a sophisticated military unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) to patrol the English Channel. The drones will relay information to both French and British border authorities, who can then intercept the crossings.[75]

In January 2021, all counter-migration operations in the English Channel were placed under the command of the Royal Navy and Operation Isotrope was launched.

In March 2021, the Home Office published a New Plan for Immigration Policy Statement, which included proposals to reform the immigration system, including the possibility of offshore processing of undocumented immigrants.[76] In April 2021, 192 refugee, human rights, and other groups signed a letter which described these proposals as "vague, unworkable, cruel and potentially unlawful".[77]

British public

According to a poll regarding use of the military to patrol the English Channel conducted by YouGov in August 2020, 73% of Britons thought the crossings to be a serious issue. Conservative voters were most concerned, with 97% thinking it serious, whereas Labour voters were least concerned, with 49%.[78]

International responses

After Abdulfatah Hamdallah drowned and washed up on French shores near Calais in August 2020, French National Assembly MP for Calais Pierre-Henri Dumont blamed the UK government for the death because of their refusal to accept asylum claims from outside the country. He also stated that migrants in Calais "do not want to seek asylum in France" and "refuse state support", preferring to "risk their lives" in rafts.[79]

See also

References

- ↑ Crystal, David, ed. (1999). "English Channel". Cambridge Paperback Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1080. ISBN 978-0521668002.

- 1 2 3 4 "Official Statistics: Irregular migration to the UK, year ending December 2022". gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ↑ "Migrants detected crossing the English Channel in small boats". gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ↑ "Refugees are increasingly using small boats to slip into the UK undetected". The Independent. 8 June 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ↑ Ross, Alice (25 August 2016). "Six men rescued from small boat off Kent coast". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 Pérez-Peña, Pérez-Peña (31 December 2018). "As Migrants Cross English Channel, Numbers Are Small but Worry Is Big". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ Bell, Melissa; Vandoorne, Saskya (6 December 2018). "Migrants risk death at sea to reach Britain as prices spike on traditional routes". CNN. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ "Calais migrants: Work begins on UK-funded border wall". BBC News. 20 September 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 Picheta, Rob (2 January 2019). "'Deeply concerning': Why the rise in migrants crossing the English Channel?". CNN. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 Campbell, Colin (27 November 2018). "Migrants 'rush to cross Channel by boat before Brexit'". BBC News. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ McLennan, William (20 January 2020). "Are migrants who cross the Channel sent back?". BBC News. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ Philip Whiteside; Isla Glaister (7 September 2020). "How many people are crossing the Channel compared with previous years and which countries are they from?". Sky News. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Channel migrants: Minister defends handling of 'crisis'". BBC News. 29 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Channel migrants: Home secretary declares major incident". BBC News. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ Harris, Tom (1 January 2019). "Why should Britain offer asylum to people who would rather not make their home in France?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ "Migrants detected crossing the English Channel in small boats". GOV.UK. 3 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ↑ "Migrants Attempt Dangerous Trip Across the Channel". CNN. 2 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Heffer, Greg (2 January 2019). "Channel migrants: What are the numbers behind the 'major incident'?". Sky News. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ↑ Topping, Alexandra (30 December 2018). "UK migrant 'crisis' bears no comparison to EU's 2015 influx". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ Campbell, Colin (20 January 2020). "English Channel migrants boats using 'surge tactics'". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- 1 2 McLennan, William (20 August 2020). "Channel crossings: Why can't the UK stop migrants in small boats?". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- 1 2 "MPs launch inquiry into increase in Channel migrant crossings". BBC News. 7 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ↑ Casciani, Dominic (7 August 2020). "Why are migrants crossing the English Channel?". BBC News. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- 1 2 Brown, Faye (6 August 2020). "Heavily pregnant woman among 235 migrants intercepted in English Channel". Metro. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ↑ "Channel migrants: 235 people in 17 vessels stopped in one day". BBC News. 7 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ↑ Grierson, Jamie; Willsher, Kim (9 August 2020). "More than 4,000 have crossed Channel to UK in small boats this year". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ↑ Braddick, Imogen (19 August 2020). "Sudanese migrant, 16, found washed up on French beach 'after boat capsizes' while crossing Channel". Evening Standard. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ↑ Grierson, Jamie; Willsher, Kim; Taylor, Diane (19 August 2020). "Teenager found dead tried to cross Channel in dinghy with shovels for oars". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ↑ Dearden, Lizzie (20 August 2020). "Channel crossings: Sudanese migrant who drowned trying to reach UK named as Abdulfatah Hamdallah". The Independent. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ↑ "Young child among migrants crossing the English Channel". www.bbc.co.uk. 20 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ↑ "Four dead, including two children, after boat sinks off French coast". www.cnn.com. 27 October 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ "Channel migrants: Kurdish-Iranian family died after boat sank". BBC News. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ "Norwegian police identify toddler who died crossing the English Channel". www.cnn.com. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ "15 måneder gamle Artin forsvant på vei fra Iran til England. To måneder senere ble han funnet død på Karmøy" [15-month-old Artin disappeared on his way from Iran to England. Two months later he was found dead on Karmøy]. www.aftenposten.no. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- 1 2 "Channel crossings: Migrant boats with 77 people on board intercepted". www.bbc.co.uk. 24 February 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ "At least 430 migrants cross Channel in single day". ITV News. 20 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ "Number of migrants crossing Channel to UK hits new daily record". BBC News. 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "Migrants deaths in Channel: 27 people die after migrant dinghy sinks off Calais - five women and girl among victims". Sky News. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ↑ "Migrant crossings: Almost 200 people cross English Channel in one day". www.bbc.co.uk. 17 January 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ↑ "Channel migrants: Almost 400 migrants cross Channel in small boats". BBC News. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ "Channel migrants: More than 500 make crossing in single weekend". www.bbc.co.uk. 9 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ↑ "More than 20,000 people have crossed the English Channel to the UK in small boats this year government figures show". Sky News. 14 August 2022.

- ↑ "Channel migrants: Almost 1,300 migrants cross Channel in new record". BBC News. 23 August 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ↑ "Channel migrants: Nearly 1,000 people cross in single day". BBC News. 30 October 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ↑ "Number of Channel migrants could hit 85,000 this year". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ↑ Dathan, Matt (24 April 2023). "Indians now second-biggest cohort of Channel migrants". The Times. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- 1 2 "Migrant boat sinks in Channel killing six people". BBC News. 12 August 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ↑ Thompson, Flora (31 August 2023). "Migrant Channel crossings top 20,000 for the year so far". The Independent. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ↑ "New Rwanda treaty on deportations in the works if judges rule against Government". The Telegraph. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ↑ "Exit from asylum hotels shows progress on illegal migration". gov.uk. Home Office. 24 October 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ↑ "Channel migrants: Crossings fell in 2023, government figures show". BBC News. 1 January 2024.

- ↑ "At Least 5 People Die Trying to Cross Icy English Channel". The New York Times. 14 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- 1 2 "Official Statistics: Irregular migration to the UK, year ending December 2022". gov.uk. Home Office. Irr_02c: Small boat arrivals, by age and sex, 2018 to 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ↑ "Government defends immigration strategy after Channel tragedy - as Tory MPs criticise 'dysfunctional' Home Office". Sky News. 13 August 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- 1 2 "Statistics relating to the Illegal Migration Act: data tables to March 2023". gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- 1 2 "Statistics relating to the Illegal Migration Act: data tables to July 2023". gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- 1 2 "Statistics relating to the Illegal Migration Act: data tables to October 2023". gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ↑ "Factsheet: Small boat crossings since July 2022". gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- 1 2 3 Henley, John (31 December 2018). "'This is the only way now': desperate Iranians attempt Channel crossing". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ "Channel migrants: Why are people crossing the English Channel?". BBC. 2 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ↑ Syal, Rajeev (25 August 2022). "Proportion of refugees granted UK asylum hits 32-year high". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ↑ Easton, Mark; May, Callum; Burns, Judith (25 August 2022). "Only 21 foreign nationals removed from UK under post-Brexit asylum rules". BBC News. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ↑ "French police nab 14 migrants at Channel port harbour". France24. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ "Migrants reach UK in stolen French fishing boat". Al Jazeera. 13 November 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ Googan, Cara (16 November 2018). "Migrants pile into dinghies to cross Channel to Dover as 'panic setting in' before Brexit deadline hits". The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ "Two held over English Channel migrant crossings". BBC News. 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ↑ "Europe | Missing Migrants Project". missingmigrants.iom.int. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ↑ "Boris Johnson holds emergency Cobra meeting after Channel deaths". www.channel4.com. 24 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ↑ "Four people dead after migrant boat incident". BBC News. 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Jamie; Hymas, Charles (31 December 2018). "Sajid Javid backs down over migrants as two more boats redeployed to the Channel". The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ↑ Swinford, Steven (2 January 2019). "Migrants crossing English Channel are not 'genuine' asylum seekers, Sajid Javid suggests". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ↑ Johnston, John (9 August 2020). "Priti Patel calls for military help to stop migrants crossing English Channel". PoliticsHome. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ↑ Grierson, Jamie; Sabbagh, Dan (10 August 2020). "Boris Johnson accused of scapegoating migrants over Channel comments". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ↑ Dearden, Lizzie (10 August 2020). "Channel Crossings: Boris Johnson calls for legal change to 'send away' more asylum seekers amid surge in migrant boats". The Independent. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ↑ "The UK is using a military drone to monitor and stop migrants from crossing the English Channel, after a record 1,400 crossed in August". Business Insider. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ↑ "New Plan for Immigration Policy Statement" (PDF). Her Majesty's Stationery Office. March 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ↑ Silva, Chantal Da (30 April 2021). "UK Accused Of Hosting 'Sham' Consultation On Refugee Policy In Letter Signed By Nearly 200 Groups". Forbes. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021.

- ↑ "Should the military patrol the English Channel?". yougov.co.uk. 13 August 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ↑ Drewett, Zoe (20 August 2020). "UK blamed for death of Sudanese boy, 16, who tried to cross Channel". Metro. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

Further reading

- Balabanova, Ekaterina; Balch, Alex (2020). "Norm Destruction, Norm Resilience: The Media and Refugee Protection in the UK and Hungary during Europe's 'Migrant Crisis'". Journal of Language and Politics. 19 (3): 413–435. doi:10.1075/jlp.19055.bal. S2CID 216363628.

- Gatrell, Peter (2019). The Unsettling of Europe: The Great Migration, 1945 to the Present. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780241290453.

- Goodman, Simon; Sirriyeh, Ala; McMahon, Simon (2017). "The Evolving (Re)Categorisations of Refugees throughout the 'Refugee/Migrant Crisis'". Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology. 27 (2): 105–114. doi:10.1002/casp.2302.

- Fotopoulos, Stergios; Kaimaklioti, Margarita (2016). "Media Discourse on the Refugee Crisis: On What Have the Greek, German and British Press Focused?". European View. 15 (2): 265–279. doi:10.1007/s12290-016-0407-5.

- Jacobs, Emma (2020). "'Colonising the Future': Migrant Crossings on the English Channel and the Discourse of Risk". Brief Encounters. 4 (1): 37–47. doi:10.24134/be.v4i1.173.

- Maggs, Joseph (2020). "The 'Channel Crossings' and the Borders of Britain". Race and Class. 61 (3): 78–86. doi:10.1177/0306396819892467. S2CID 212982927.

- Parker, Samuel (2015). "'Unwanted Invaders': The Representation of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK and Australian Print Media" (PDF). ESharp. 23 (1): 1–21.

- Parker, Samuel; Bennett, Sophie; Cobden, Chyna Mae; Earnshaw, Deborah (2021). "'It's Time We Invested in Stronger Borders': Media Representations of Refugees Crossing the English Channel by Boat". Critical Discourse Studies. 19 (4): 348–363. doi:10.1080/17405904.2021.1920998. S2CID 235526695.