An Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) is defined by International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 14025 as a Type III declaration that "quantifies environmental information on the life cycle of a product to enable comparisons between products fulfilling the same function."[1] The EPD methodology is based on the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)[2] tool that follows ISO series 14040.[3][4][5]

EPDs are primarily intended to facilitate business-to-business transactions, although they may also be of benefit to consumers who are environmentally focused when choosing goods or services.[3][4][5][6] Companies implement EPDs in order to improve their sustainability goals, and to demonstrate a commitment to the environment to customers.[6]

Content of EPDs

EPD reports are available from The International EPD System[7] database. Specific content will vary according to the category of the product, but most summarize environmental information on the product in fewer than 50 pages. The text and illustrations are designed to be easily understood by consumers and retailers.

As an example, a 38-page EPD for a pasta product contains sections on the brand and product, environmental performance calculations, information on sustainable wheat cultivation, milling, packaging production, pasta production, distribution, cooking, packaging end-of-life, and summary tables for environmental results in different markets.[8]

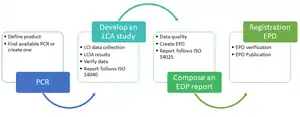

Framework for creating an EPD

The first step in creating an EPD is defining the product, using the appropriate Product Category Rules (PCR). PCRs are specific rules and requirements verified by an independent, third-party panel. A Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) for the LCA must be verified and from reliable sources (for example, from a manufacturing facility). A Life Cycle Environmental Impact Analysis (LCIA) is performed by an LCA expert using software and a variety of assessment tools.[9] The EPD is delivered as a document or report following a series of verification reviews; it is then ready for registration and publication.[10][3][4][5][6] [11]

Product category rules

Environmental Product Declarations follow Life Cycle Assessment methodology. However, LCA studies can vary in terms of assumptions and information included. Consequently, the results for products that fulfill the same function may not be consistent with one another.[12][13]

Product Category Rules (PCRs) provide guidance that enables fair comparison among products of the same category. PCRs include the description of the product category, the goal of the LCA, functional units, system boundaries, cut-off criteria, allocation rules, impact categories, information on the use phase, units, calculation procedures, requirements for data quality, and other information.[14] The goal of PCRs is to help develop EPDs for products that are comparable to others within a product category.[15] ISO 14025 establishes the procedure for developing PCRs and the required content of a PCR, as well as requirements for comparability.[16]

Duplication in PCRs for similar products in different countries arises from the different purposes of the PCRs, the varying standards they were based on, or the use of different product categorization systems.[17] Different interpretations of PCR's can cause variances in data reporting within a product category.

However, EPDs that are effective require the use of standard factors in their formulation. Global harmonization of PCR and EPD standards remains a challenge.[18]

Challenges in Creating EPDs

- Diverse range of PCR's: The presence and adaptation of non-uniform PCR's for the same product lead to fluctuating and varying EPD's, which leads to a fallacious comparison between the products. PCRs vary according to the geographical scope of the product, lack of specific standards of data and lack of coordination between program operators.[19]

- Complex and inconsistent database: Due to the complex and time-consuming nature of data collection procedures, the Life Cycle Assessment requirement for an EPD becomes prolonged.[20] Due to lack of precise site-specific data and the use of generic data over specific data can leads to inaccurate declarations. Report CEN 15941 states, "generic data should never replace specific data when specific data are available".[21][22]

- Lack of satisfactory and acceptable third-party critical review: Inconsistency in sharing a common view on specific aspects and reviewing of only general aspects, leaving out more specific aspects, leads to varying interpretations of EPDs for similar products.[23]

- Financial Constraints: Due to financial constraints in small scale companies and industries, publishing an EPD after performing an LCA becomes very cost-intensive.[24][25]

- Incomplete formation and interpretation of results: Due to the unavailability of EPD's and PCR's for many products, it becomes very difficult to publish a complete and elaborate EPD for a product which involves the previous products in their life cycle. Lack of transparency in declaration procedure and uniform interpretation leads to an inconsistent comparison between products.[26]

EPDs in Europe

In Europe, the European Committee for Standardization has published EN 15804, a common Product Category Rules (PCR) for EPD development in the construction sector. Other complementary standards, for example for environmental building assessment (EN 15978) were also published by this Technical Committee.

In order to enhance harmonization, the main Programme Operators for EPD verification in the construction sector created the Association ECO Platform, with members from different European countries. The Programme Operators approved to issue EPD with the ECO Platform verified logo[27] are:

- 2014:

- Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR) - GlobalEPD Program (Spain)

- Bau EPD GmbH (Austria)

- EPD International AB - International EPD System (Sweden)

- Institut Bauen und Umwelt e.V. (IBU) (Germany)

- 2015:

- Building Research Establishment Limited (BRE) (United Kingdom)

- EPD Danmark (Danmark)

- Instytut Techniki Budowlanej (Poland)

- 2016:

- Association HQE tio - FDES INIES (France)

- ICMQ S.p.a. - EPDItaly (Italy)

- DAPHabitat - DAPHabitat System (Portugal)

- 2018:

The ECO Platform also includes Associations:

- Construction Products Europe

- Ceramie Unie ASBL

- Eurima AiSBL

Some of these Programme Operators are under bilateral mutual recognition agreements:[28] IBU (Germany), EPD International (Sweden) and AENOR GlobalEPD (Spain).

EPDs in North America and Asia

Although the European-based EPD programs constitute a large portion of EPD programs all over the world, there are a number of North America and Asia EPD schemes:[5][3][29]

- North America

- FP Innovations - EPD Program on Wood Products (Canada)[30]

- NSF International (U.S.)[31]

- The Institute for Environmental Research & Education - Earthsure EPD (U.S.)[32]

- The Sustainability Consortium (U.S.)[33]

- UL Environment (U.S.)[34]

- ASTM International (U.S.)[35]

- Carbon Leadership Forum (U.S.)[36]

- ICC Evaluation Services (U.S.)[37]

- National Ready Mixed Concrete Association (U.S.)[38]

- SCS Global Services (U.S.)[39]

- Asia

See also

References

- ↑ "Environmental labels and declarations - Type III environmental declarations - Principles and procedures". Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ↑ Matthews, H. Scott; Hendrickson, Chris T.; Deanna H., Matthews (2015). "4". Life Cycle Assessment: quantitative approaches for Decisions that Matter. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike. pp. 88–95.

- 1 2 3 4 Del Borghi, Adriana (10 October 2012). "LCA and communication: Environmental Product Declaration". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 18 (2): 293–295. doi:10.1007/s11367-012-0513-9. ISSN 0948-3349.

- 1 2 3 Manzini, Raffaella; Noci, Giuliano; Ostinelli, Massimiliano; Pizzurno, Emanuele (2006). "Assessing environmental product declaration opportunities: a reference framework". Business Strategy and the Environment. 15 (2): 118–134. doi:10.1002/bse.453. ISSN 0964-4733.

- 1 2 3 4 Minkov, Nikolay; Schneider, Laura; Lehmann, Annekatrin; Finkbeiner, Matthias (May 2015). "Type III Environmental Declaration Programmes and harmonisation of product category rules: status quo and practical challenges". Journal of Cleaner Production. 94: 235–246. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.012. ISSN 0959-6526.

- 1 2 3 Allander, A (July 2001). "Successful Certification of an Environmental Product Declaration for an ABB Product". Corporate Environmental Strategy. 8 (2): 133–141. doi:10.1016/s1066-7938(01)00094-x. ISSN 1066-7938.

- ↑ "International EPD System".

- ↑ Barilla. 26 Sep 2013. Durum wheat semolina pasta in paperboard box: Environmental Product Declaration. Revision 8 of 7 November 2019.

- ↑ WBSCD (29 September 2014). "Life Cycle Metrics for Chemical Products". Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ↑ Stahel, Walter R. (24 March 2016). "Circular Economy". Nature. 531 (2016): 435–8. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..435S. doi:10.1038/531435a. PMID 27008952. ProQuest 1776790666.

- ↑ "How to get an EPD". Building Transparency. 19 April 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ↑ Teehan, Paul; Kandlikar, Milind (20 March 2012). "Sources of Variation in Life Cycle Assessments of Desktop Computers". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 16: S182–S194. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2011.00431.x. ISSN 1088-1980.

- ↑ Säynäjoki, Antti; Heinonen, Jukka; Junnila, Seppo; Horvath, Arpad (5 January 2017). "Can life-cycle assessment produce reliable policy guidelines in the building sector?". Environmental Research Letters. 12 (1): 013001. Bibcode:2017ERL....12a3001S. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa54ee. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ↑ Almeida, Marisa Isabel; Dias, Ana Cláudia; Demertzi, Martha; Arroja, Luís (2015). "Contribution to the Development of Product Category Rules for Ceramic Bricks". Journal of Cleaner Production. 92: 206–215. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.073. hdl:10773/16706 – via Elsevier ScienceDirect.

- ↑ Ingwersen, Wesley W.; Stevenson, Martha J. (2012). "Can we compare the environmental performance of this product to that one? An update on the development of product category rules and future challenges toward alignment". Journal of Cleaner Production. 24: 102–108. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.10.040. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ↑ Environmental labels and declarations. Type III environmental declarations. Principles and procedures, International Organization for Standardization, retrieved 26 April 2019

- ↑ Subramanian, Vairavan; Ingwersen, Wesley; Hensler, Connie; Collie, Heather (20 April 2012). "Comparing product category rules from different programs: learned outcomes towards global alignment". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 17 (7): 892–903. doi:10.1007/s11367-012-0419-6. ISSN 0948-3349.

- ↑ "Global PCR harmonization - The International EPD® System". www.environdec.com. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ↑ Ingwersen, Wesley & Subramanian, Vairavan & Scarinci, Carolina & Mlsna, Alexander & Koffler, Christoph & Assefa Wondimagegnehu, Getachew & Imbeault-Tétreault, Hugues & Mahalle, Lal & Sertich, Maureen & Costello, Mindy & Firth, Paul. (2013). Guidance for Product Category Rule Development. 10.13140/2.1.3007.1844.

- ↑ Fet, A. M., Skaar, C., & Michelsen, O. (2008). Product category rules and environmental product declarations as tools to promote sustainable products: experiences from a case study of furniture production. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 11(2), 201–207. doi:10.1007/s10098- 008-0163-6

- ↑ Modahl, I. S., Askham, C., Lyng, K.-A., Skjerve-Nielssen, C., & Nereng, G. (2012). Comparison of two versions of an EPD, using generic and specific data for the foreground system, and some methodological implications. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 18(1), 241– 251.doi:10.1007/s11367-012-0449-0

- ↑ PD CEN/TR 15941 (2010) Sustainability of construction works. Environmental product declarations. Methodology for selection and use of generic data. BSI (British Standards Institution).

- ↑ Sébastien Lasvaux, Yann Leroy, Capucine Briquet, Jacques Chevalier. International Survey on Critical Review and Verification Practices in LCA with a Focus in the Construction Sector. 6th International Conference on Life Cycle Management - LCM 2013, Aug 2013, Gothenburg, Sweden. hal-01790869

- ↑ Fet, A. M., & Skaar, C. (2006). Eco-labelling, Product Category Rules and Certification Procedures Based on ISO 14025 Requirements (6 pp). The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 11(1), 49–54. doi:10.1065/lca2006.01.237

- ↑ Tasaki, T., Shobatake, K., Nakajima, K., & Dalhammar, C. (2017). International Survey of the Costs of Assessment for Environmental Product Declarations. Procedia CIRP, 61, 727– 731.doi:10.1016/j.procir.2016.11.158

- ↑ Gelowitz, M. D. C., & McArthur, J. J. (2016). Investigating the Effect of Environmental Product Declaration Adoption in LEED® on the Construction Industry: A Case Study. Procedia Engineering, 145, 58–65. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.04.014

- ↑ "Programme Operators in ECO Platform". ECO Platform.

- ↑ "Bilateral agreements and international recognitions". AENOR. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Hunsager, Einar Aalen; Bach, Martin; Breuer, Lutz (2014). "An institutional analysis of EPD programs and a globaal PCR registry". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 19 (4): 786–795. doi:10.1007/s11367-014-0711-8. ISSN 1614-7502.

- ↑ "FP Innovations EPD Programs". Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ↑ "NSF International EPD Programs".

- ↑ "The Institute for Environmental Research & Education". Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ↑ "The Sustainability Consortium".

- ↑ "UL Environment EPD".

- ↑ "ASTM Internation EPD".

- ↑ "Carbon Leadership Forum Projects".

- ↑ "ICC Evaluation Services EPD".

- ↑ "NRMCA EPD Program".

- ↑ "SGS Global Services EPD".

- ↑ "JEMAI CPF Program".

- ↑ "Korean Environmental Industry & Technology Institute".

- ↑ "Environment and Development Foundation".