| |

| Halakhic texts relating to this article | |

|---|---|

| Torah: | Exodus 20:7–10, Deut 5:12–14, numerous others.[1] |

| Mishnah: | Shabbat, Eruvin |

| Babylonian Talmud: | Shabbat, Eruvin |

| Jerusalem Talmud: | Shabbat, Eruvin |

| Mishneh Torah: | Sefer Zmanim, Shabbat 1–30; Eruvin 1–8 |

| Shulchan Aruch: | Orach Chayim, Shabbat 244–344; Eruvin 345–395; Techumin 396–416 |

| Other rabbinic codes: | Kitzur Shulchan Aruch ch. 72–96 |

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

Shabbat (UK: /ʃəˈbæt/, US: /ʃəˈbɑːt/, or /ʃəˈbʌt/; Hebrew: שַׁבָּת, romanized: Šabbāṯ, [ʃa'bat], lit. 'rest' or 'cessation') or the Sabbath (/ˈsæbəθ/), also called Shabbos (UK: /ˈʃæbəs/, US: /ˈʃɑːbəs/) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical stories describing the creation of the heaven and earth in six days and the redemption from slavery and the Exodus from Egypt, and look forward to a future Messianic Age. Since the Jewish religious calendar counts days from sunset to sunset, Shabbat begins in the evening of what on the civil calendar is Friday.

Shabbat observance entails refraining from work activities, often with great rigor, and engaging in restful activities to honor the day. Judaism's traditional position is that the unbroken seventh-day Shabbat originated among the Jewish people, as their first and most sacred institution. Variations upon Shabbat are widespread in Judaism and, with adaptations, throughout the Abrahamic and many other religions.

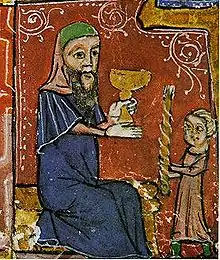

According to halakha (Jewish religious law), Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before the sun sets on Friday evening until the appearance of three stars in the sky on Saturday night, or an hour after sundown.[2] Shabbat is ushered in by lighting candles and reciting blessings over wine and bread. Traditionally, three festive meals are eaten: The first one is held on Friday evening, the second is traditionally a lunch meal on Saturday, and the third is held later Saturday afternoon. The evening meal and the early afternoon meal typically begin with a blessing called kiddush (sanctification), said over a cup of wine.

At the third meal a kiddush is not performed, but the hamotzi blessing is recited and challah (braided bread) is eaten. In many communities, this meal is often eaten in the period after the afternoon prayers (Minchah) are recited and shortly before Shabbat is formally ended with a Havdalah ritual.

Shabbat is a festive day when Jews exercise their freedom from the regular labours of everyday life. It offers an opportunity to contemplate the spiritual aspects of life and to spend time with family. The end of Shabbat is traditionally marked by a ritual called Havdalah, during which blessings are said over wine (or grape juice), aromatic spices, and light, separating Shabbat from the rest of the week.[3]

Etymology

The word Shabbat derives from the Hebrew root ש־ב־ת. Although frequently translated as "rest" (noun or verb), another accurate translation is "ceasing [from work]."[4] The notion of active cessation from labour is also regarded as more consistent with an omnipotent God's activity on the seventh day of creation according to Genesis.

Origins

Babylon

A cognate Babylonian Sapattum or Sabattum is reconstructed from the lost fifth Enūma Eliš creation account, which is read as: "[Sa]bbatu shalt thou then encounter, mid[month]ly". It is regarded as a form of Sumerian sa-bat ("mid-rest"), rendered in Akkadian as um nuh libbi ("day of mid-repose").[5]

Connection to Sabbath observance has been suggested in the designation of the seventh, fourteenth, nineteenth, twenty-first and twenty-eight days of a lunar month in an Assyrian religious calendar as a 'holy day', also called 'evil days' (meaning "unsuitable" for prohibited activities). The prohibitions on these days, spaced seven days apart (except the nineteenth), include abstaining from chariot riding, and the avoidance of eating meat by the King. On these days officials were prohibited from various activities and common men were forbidden to "make a wish", and at least the 28th was known as a "rest-day".[6][7]

The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia advanced a theory of Assyriologists like Friedrich Delitzsch[8] (and of Marcello Craveri)[9] that Shabbat originally arose from the lunar cycle in the Babylonian calendar[10][11] containing four weeks ending in a Sabbath, plus one or two additional unreckoned days per month.[12] The difficulties of this theory include reconciling the differences between an unbroken week and a lunar week, and explaining the absence of texts naming the lunar week as Sabbath in any language.[13]

Egypt

Seventh-day Shabbat did not originate with the Egyptians, to whom it was unknown;[14] and other origin theories based on the day of Saturn, or on the planets generally, have also been abandoned.[13]

Hebrew Bible

Sabbath is given special status as a holy day at the very beginning of the Torah in Genesis 2:1-3.[15] It is first commanded after The Exodus from Egypt, in Exodus 16:26[16] (relating to the cessation of manna) and in Exodus 16:29[17] (relating to the distance one may travel by foot on the Sabbath), as also in Exodus 20:8-11[18] (as one of the Ten Commandments). Sabbath is commanded and commended many more times in the Torah and Tanakh; double the normal number of animal sacrifices are to be offered on the day.[19] Sabbath is also described by the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Hosea, Amos, and Nehemiah.

The longstanding Jewish position is that unbroken seventh-day Shabbat originated among the Jewish people, as their first and most sacred institution.[8] The origins of Shabbat and a seven-day week are not clear to scholars; the Mosaic tradition claims an origin from the Genesis creation narrative.[20][21]

The first non-Biblical reference to Sabbath is in an ostracon found in excavations at Mesad Hashavyahu, which has been dated to approximately 630 BCE.[22]

Status as a Jewish holy day

_-_%D7%9B%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%95%D7%99_%D7%94%D7%97%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%AA_-_Challah_cover.JPG.webp)

The Tanakh and siddur describe Shabbat as having three purposes:

- To commemorate God's creation of the universe, on the seventh day of which God rested from (or ceased) his work;

- To commemorate the Israelites' Exodus and redemption from slavery in ancient Egypt;

- As a "taste" of Olam Haba (the Messianic Age).

Judaism accords Shabbat the status of a joyous holy day. In many ways, Jewish law gives Shabbat the status of being the most important holy day in the Hebrew calendar:[23]

- It is the first holy day mentioned in the Bible, and God was the first to observe it with the cessation of creation (Genesis 2:1–3).

- Jewish liturgy treats Shabbat as a "bride" and "queen" (see Shekhinah); some sources described it as a "king".[24]

- The Sefer Torah is read during the Torah reading which is part of the Shabbat morning services, with a longer reading than during the week. The Torah is read over a yearly cycle of 54 parashioth, one for each Shabbat (sometimes they are doubled). On Shabbat, the reading is divided into seven sections, more than on any other holy day, including Yom Kippur. Then, the Haftarah reading from the Hebrew prophets is read.

- A tradition states that the Jewish Messiah will come if every Jew properly observes two consecutive Shabbatoth.[25]

- The punishment in ancient times for desecrating Shabbat (stoning) is the most severe punishment in Jewish law.[26] In addition, the divine punishment for desecrating Shabbat, kareth (spiritual excommunication), is the most severe of divine punishments in Judaism.[27]

- On Shabbat an offering of two lambs was brought in the temple in Jerusalem.[28]

Rituals

Welcoming Shabbat

Honoring Shabbat (kavod Shabbat) on Preparation Day (Friday) includes bathing, having a haircut and cleaning and beautifying the home (with flowers, for example). Days in the Jewish calendar start at nightfall, therefore many Jewish holidays begin at such time.[29] According to Jewish law, Shabbat starts a few minutes before sunset. Candles are lit at this time. It is customary in many communities to light the candles 18 minutes before sundown (tosefet Shabbat, although sometimes 36 minutes), and most printed Jewish calendars adhere to this custom.

The Kabbalat Shabbat service is a prayer service welcoming the arrival of Shabbat. Before Friday night dinner, it is customary to sing two songs, one "greeting" two Shabbat angels into the house[30] ("Shalom Aleichem" -"Peace Be Upon You") and the other praising the woman of the house for all the work she has done over the past week ("Eshet Ḥayil" -"Women Of Valour").[31] After blessings over the wine and challah, a festive meal is served. Singing is traditional at Sabbath meals.[32] In modern times, many composers have written sacred music for use during the Kabbalat Shabbat observance, including Robert Strassburg[33] and Samuel Adler.[34]

According to rabbinic literature, God via the Torah commands Jews to observe (refrain from forbidden activity) and remember (with words, thoughts, and actions) Shabbat, and these two actions are symbolized by the customary two Shabbat candles. Candles are lit usually by the woman of the house (or else by a man who lives alone). Some families light more candles, sometimes in accordance with the number of children.[35]

Other rituals

Shabbat is a day of celebration as well as prayer. It is customary to eat three festive meals: Dinner on Shabbat eve (Friday night), lunch on Shabbat day (Saturday), and a third meal (a Seudah shlishit[36]) in the late afternoon (Saturday). It is also customary to wear nice clothing (different from during the week) on Shabbat to honor the day.

Many Jews attend synagogue services on Shabbat even if they do not do so during the week. Services are held on Shabbat eve (Friday night), Shabbat morning (Saturday morning), and late Shabbat afternoon (Saturday afternoon).

With the exception of Yom Kippur, days of public fasting are postponed or advanced if they coincide with Shabbat. Mourners sitting shivah (week of mourning subsequent to the death of a spouse or first-degree relative) outwardly conduct themselves normally for the duration of the day and are forbidden to display public signs of mourning.

Although most Shabbat laws are restrictive, the fourth of the Ten Commandments in Exodus is taken by the Talmud and Maimonides to allude to the positive commandments of Shabbat. These include:

- Honoring Shabbat (kavod Shabbat): on Shabbat, wearing festive clothing and refraining from unpleasant conversation. It is customary to avoid talking on Shabbat about money, business matters, or secular things that one might discuss during the week.[37][38]

- Recitation of kiddush over a cup of wine at the beginning of Shabbat meals, or at a reception after the conclusion of morning prayers (see the list of Jewish prayers and blessings).

- Eating three festive meals. Meals begin with a blessing over two loaves of bread (lechem mishneh, "double bread"), usually of braided challah, which is symbolic of the double portion of manna that fell for the Jewish people on the day before Sabbath during their 40 years in the desert after the Exodus from Ancient Egypt. It is customary to serve meat or fish, and sometimes both, for Shabbat evening and morning meals. Seudah Shlishit (literally, "third meal"), generally a light meal that may be pareve or dairy, is eaten late Shabbat afternoon.

- Enjoying Shabbat (oneg Shabbat): Engaging in pleasurable activities such as eating, singing, sleeping, spending time with the family, and marital relations. Sometimes referred to as "Shabbating".

- Recitation of havdalah.

Bidding farewell

Havdalah (Hebrew: הַבְדָּלָה, "separation") is a Jewish religious ceremony that marks the symbolic end of Shabbat, and ushers in the new week. At the conclusion of Shabbat at nightfall, after the appearance of three stars in the sky, the havdalah blessings are recited over a cup of wine, and with the use of fragrant spices and a candle, usually braided. Some communities delay havdalah later into the night in order to prolong Shabbat. There are different customs regarding how much time one should wait after the stars have surfaced until the sabbath technically ends. Some people hold by 72 minutes later and other hold longer and shorter than that.

Prohibited activities

Jewish law (halakha) prohibits doing any form of melakhah (מְלָאכָה, plural melakhoth) on Shabbat, unless an urgent human or medical need is life-threatening. Though melakhah is commonly translated as "work" in English, a better definition is "deliberate activity" or "skill and craftmanship". There are 39 categories of melakhah:[39]

- plowing earth

- sowing

- reaping

- binding sheaves

- threshing

- winnowing

- selecting

- grinding

- sifting

- kneading

- baking

- shearing wool

- washing wool

- beating wool

- dyeing wool

- spinning

- weaving

- making two loops

- weaving two threads

- separating two threads

- tying

- untying

- sewing stitches

- tearing

- trapping

- slaughtering

- flaying

- tanning

- scraping hide

- marking hide

- cutting hide to shape

- writing two or more letters

- erasing two or more letters

- building

- demolishing

- extinguishing a fire

- kindling a fire

- putting the finishing touch on an object, and

- transporting an object (between private and public domains, or over 4 cubits within public domain)

The 39 melakhoth are not so much activities as "categories of activity". For example, while "winnowing" usually refers exclusively to the separation of chaff from grain, and "selecting" refers exclusively to the separation of debris from grain, they refer in the Talmudic sense to any separation of intermixed materials which renders edible that which was inedible. Thus, filtering undrinkable water to make it drinkable falls under this category, as does picking small bones from fish (gefilte fish is one solution to this problem).

The categories of labors prohibited on Shabbat are exegetically derived – on account of Biblical passages juxtaposing Shabbat observance (Exodus 35:1–3) to making the Tabernacle (Exodus 35:4 etc.) – that they are the kinds of work that were necessary for the construction of the Tabernacle. They are not explicitly listed in the Torah; the Mishnah observes that "the laws of Shabbat ... are like mountains hanging by a hair, for they are little Scripture but many laws".[40] Many rabbinic scholars have pointed out that these labors have in common activity that is "creative", or that exercises control or dominion over one's environment.[41]

In addition to the 39 melakhot, additional activities were prohibited by the rabbis for various reasons.

The term shomer Shabbat is used for a person (or organization) who adheres to Shabbat laws consistently. The (strict) observance of the Sabbath is often seen as a benchmark for orthodoxy and indeed has legal bearing on the way a Jew is seen by an orthodox religious court regarding their affiliation to Judaism.[42]

Specific applications

Electricity

Orthodox and some Conservative authorities rule that turning electric devices on or off is prohibited as a melakhah; however, authorities are not in agreement about exactly which one(s). One view is that tiny sparks are created in a switch when the circuit is closed, and this would constitute lighting a fire (category 37). If the appliance is purposed for light or heat (such as an incandescent bulb or electric oven), then the lighting or heating elements may be considered as a type of fire that falls under both lighting a fire (category 37) and cooking (i.e., baking, category 11). Turning lights off would be extinguishing a fire (category 36). Another view is that completing an electrical circuit constitutes building (category 35) and turning off the circuit would be demolishing (category 34). Some schools of thought consider the use of electricity to be forbidden only by rabbinic injunction, rather than a melakhah.

A common solution to the problem of electricity involves preset timers (Shabbat clocks) for electric appliances, to turn them on and off automatically, with no human intervention on Shabbat itself. Some Conservative authorities[44][45][46] reject altogether the arguments for prohibiting the use of electricity. Some Orthodox also hire a "Shabbos goy", a Gentile to perform prohibited tasks (like operating light switches) on Shabbat.

Automobiles

Orthodox and many Conservative authorities completely prohibit the use of automobiles on Shabbat as a violation of multiple categories, including lighting a fire, extinguishing a fire, and transferring between domains (category 39). However, the Conservative movement's Committee on Jewish Law and Standards permits driving to a synagogue on Shabbat, as an emergency measure, on the grounds that if Jews lost contact with synagogue life, they would become lost to the Jewish people.

A halakhically authorized Shabbat mode added to a power-operated mobility scooter may be used on the observance of Shabbat for those with walking limitations, often referred to as a Shabbat scooter. It is intended only for individuals whose limited mobility is dependent on a scooter or automobile consistently throughout the week.

Modifications

Seemingly "forbidden" acts may be performed by modifying technology such that no law is actually violated. In Sabbath mode, a "Sabbath elevator" will stop automatically at every floor, allowing people to step on and off without anyone having to press any buttons, which would normally be needed to work. (Dynamic braking is also disabled if it is normally used, i.e., shunting energy collected from downward travel, and thus the gravitational potential energy of passengers, into a resistor network.) However, many rabbinical authorities consider the use of such elevators by those who are otherwise capable as a violation of Shabbat, with such workarounds being for the benefit of the frail and handicapped and not being in the spirit of the day.

Many observant Jews avoid the prohibition of carrying by use of an eruv. Others make their keys into a tie bar, part of a belt buckle, or a brooch, because a legitimate article of clothing or jewelry may be worn rather than carried. An elastic band with clips on both ends, and with keys placed between them as integral links, may be considered a belt.

Shabbat lamps have been developed to allow a light in a room to be turned on or off at will while the electricity remains on. A special mechanism blocks out the light when the off position is desired without violating Shabbat.

The Shabbos App is a proposed Android app claimed by its creators to enable Orthodox Jews, and all Jewish Sabbath-observers, to use a smartphone to text on the Jewish Sabbath. It has met with resistance from some authorities.[47][48][49][50]

Permissions

If a human life is in danger (pikuach nefesh), then a Jew is not only allowed, but required,[51][52] to violate any halakhic law that stands in the way of saving that person (excluding murder, idolatry, and forbidden sexual acts). The concept of life being in danger is interpreted broadly: for example, it is mandated that one violate Shabbat to bring a woman in active labor to a hospital. Lesser rabbinic restrictions are often violated under much less urgent circumstances (a patient who is ill but not critically so).

We did everything to save lives, despite Shabbat. People asked: "Why are you here? There are no Jews here," but we are here because the Torah orders us to save lives .... We are desecrating Shabbat with pride.

Various other legal principles closely delineate which activities constitute desecration of Shabbat. Examples of these include the principle of shinui ("change" or "deviation"): A violation is not regarded as severe if the prohibited act was performed in a way that would be considered abnormal on a weekday. Examples include writing with one's nondominant hand, according to many rabbinic authorities. This legal principle operates bedi'avad (ex post facto) and does not cause a forbidden activity to be permitted barring extenuating circumstances.

Reform and Reconstructionist views

Generally, adherents of Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism believe that the individual Jew determines whether to follow Shabbat prohibitions or not. For example, some Jews might find activities, such as writing or cooking for leisure, to be enjoyable enhancements to Shabbat and its holiness, and therefore may encourage such practices. Many Reform Jews believe that what constitutes "work" is different for each person, and that only what the person considers "work" is forbidden.[54] The radical Reform rabbi Samuel Holdheim advocated moving Sabbath to Sunday for many no longer observed it, a step taken by dozens of congregations in the United States in late 19th century.[55]

More rabbinically traditional Reform and Reconstructionist Jews believe that these halakhoth in general may be valid, but that it is up to each individual to decide how and when to apply them. A small fraction of Jews in the Progressive Jewish community accept these laws in much the same way as Orthodox Jews.

Encouraged activities

The Talmud, especially in tractate Shabbat, defines rituals and activities to both "remember" and "keep" the Sabbath and to sanctify it at home and in the synagogue. In addition to refraining from creative work, the sanctification of the day through blessings over wine, the preparation of special Sabbath meals, and engaging in prayer and Torah study were required as an active part of Shabbat observance to promote intellectual activity and spiritual regeneration on the day of rest from physical creation. The Talmud states that the best food should be prepared for the Sabbath, for "one who delights in the Sabbath is granted their heart's desires" (BT, Shabbat 118a-b).[56][57]

All Jewish denominations encourage the following activities on Shabbat:

- Reading, studying, and discussing Torah and commentary, Mishnah and Talmud, and learning some halakha and midrash.

- Synagogue attendance for prayers.

- Spending time with other Jews and socializing with family, friends, and guests at Shabbat meals (hachnasat orchim, "hospitality").

- Singing zemiroth or niggunim, special songs for Shabbat meals (commonly sung during or after a meal).

- Sex between husband and wife.[58]

- Sleeping.

Special Shabbat

Special Shabbatot are the Shabbatot that precede important Jewish holidays: e.g., Shabbat HaGadol (Shabbat preceding Pesach), Shabbat Zachor (Shabbat preceding Purim), and Shabbat Shuvah (Shabbat between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur).

In other religions

Christianity

Most Christians do not observe Saturday Sabbath, but instead observe a weekly day of worship on Sunday, which is often called the "Lord's Day". Several Christian denominations, such as the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Church of God (7th Day), the Seventh Day Baptists, and others, observe seventh-day Sabbath. This observance is celebrated from Friday sunset to Saturday sunset.

Samaritans

Samaritans also observe Shabbat.[59][60]

Lunar Sabbath

Some hold the biblical sabbath was not connected to a 7-day week like the Gregorian calendar.[61] Instead the New Moon marks the starting point for counting and the shabbat falls consistently on the 8th, 15th, 22nd, 29th of each month. Biblical text to support using the moon, a light in the heavens, to determine days include Genesis 1:14, Psalm 104:19, and Sirach 43:6–8 See references: [62][63][64]

Rabbinic Jewish tradition and practice does not hold of this, holding the sabbath to be based of the days of creation, and hence a wholly separate cycle from the monthly cycle, which does not occur automatically and must be rededicated each month.[65] See kiddush hachodesh.

See also

References

- ↑ Other Biblical sources include: Exodus 16:22–30, Exodus 23:12, Exodus 31:12–17, Exodus 34:21, and Exodus 35: 12–17; Leviticus 19:3, Leviticus 23:3, Leviticus 26:2 and Numbers 15:32–26

- ↑ Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chayim 293:2

- ↑ "The Ultimate Guide to Jewish Holidays". 8 January 2020.

- ↑ "Sabbath | Judaism". Britannica. April 18, 2023.

- ↑ Pinches, T.G. (2003). "Sabbath (Babylonian)". In Hastings, James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. 20. Selbie, John A., contrib. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 889–891. ISBN 978-0-7661-3698-4. Retrieved 2009-03-17. It has been argued that the association of the number seven with creation itself derives from the circumstance that the Enuma Elish was recorded on seven tablets. "emphasized by Professor Barton, who says: 'Each account is arranged in a series of sevens, the Babylonian in seven tablets, the Hebrew in seven days. Each of them places the creation of man in the sixth division of its series." Albert T. Clay, The Origin of Biblical Traditions: Hebrew Legends in Babylonia and Israel, 1923, p. 74.

- ↑ "Histoire du peuple hébreu". André Lemaire. Presses Universitaires de France 2009 (8e édition), p. 66

- ↑ Zerubavel, Eviatar (1985). The Seven Day Circle: The History and Meaning of the Week. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-98165-7.

- 1 2 Landau, Judah Leo. The Sabbath. Johannesburg, South Africa: Ivri Publishing Society, Ltd. pp. 2, 12. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ Craveri, Marcello (1967). The Life of Jesus. Grove Press. p. 134.

- ↑ Joseph, Max (1943). "Holidays". In Landman, Isaac (ed.). The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: An authoritative and popular presentation of Jews and Judaism since the earliest times. Vol. 5. Cohen, Simon, compiler. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc. p. 410.

- ↑ Joseph, Max (1943). "Sabbath". In Landman, Isaac (ed.). The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: An authoritative and popular presentation of Jews and Judaism since the earliest times. Vol. 9. Cohen, Simon, compiler. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Incv. p. 295.

- ↑ Cohen, Simon (1943). "Week". In Landman, Isaac (ed.). The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: An authoritative and popular presentation of Jews and Judaism since the earliest times. Vol. 10. Cohen, Simon, compiler. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc. p. 482.

- 1 2 Sampey, John Richard (1915). "Sabbath: Critical Theories". In Orr, James (ed.). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Howard-Severance Company. p. 2630. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ↑ Bechtel, Florentine (1912). "Sabbath". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York City: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ Genesis 2:1–3

- ↑ Exodus 16:26

- ↑ Exodus 16:29

- ↑ Exodus 20:8–11

- ↑ Every Person's Guide to Shabbat, by Ronald H. Isaacs, Jason Aronson, 1998, p. 6

- ↑ Graham, I. L. (2009). "The Origin of the Sabbath". Presbyterian Church of Eastern Australia. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ "Jewish religious year: The Sabbath". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

According to biblical tradition, it commemorates the original seventh day on which God rested after completing the creation. Scholars have not succeeded in tracing the origin of the seven-day week, nor can they account for the origin of the Sabbath.

- ↑ "Mezad Hashavyahu Ostracon, c. 630 BCE". Archived from the original on 2013-01-30. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ One measure is the number of people called up to Torah readings at the Shachrit/morning service. Three is the smallest number, e.g. Mondays and Thursdays. Five on the Holy days of Passover, Shavuoth, Succoth. Yom Kippur: Six. Shabbat: Seven.

- ↑ The Talmud (Shabbat 119a) describes rabbis going out to greet the Shabbat Queen, and the Lekhah Dodi poem describes Shabbat as a "bride" and "queen". However, Maimonides (Mishneh Torah Hilchot Shabbat 30:2) speaks of greeting the "Shabbat King", and two independent commentaries on Mishneh Torah (Maggid Mishneh and R' Zechariah haRofeh) quote the Talmud as speaking of the "Shabbat King". The words "King" and "Queen" in Aramaic differ by just one letter, and it seems that these understandings result from different traditions regarding spelling the Talmudic word. See full discussion.

- ↑ Shabbat 118

- ↑ See e.g. Numbers 15:32–36.

- ↑ Rambam's commentary on the Mishna, tractate of Avot, Chapter 2 a. (he)

- ↑ Numbers 28:9.

- ↑ Moss, Aron. "Why do Jewish holidays begin at nightfall?". Chabad.org. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ↑ Shabbat 119b

- ↑ Proverbs 31:10–31

- ↑ Ferguson, Joey (May 20, 2011). "Jewish lecture series focuses on Sabbath Course at Chabad center focuses on secrets of sabbath's serenity". Deseret News.

The more we are able to invest in it, the more we are able to derive pleasure from the Sabbath." Jewish belief is based on understanding that observance of the Sabbath is the source of all blessing, said Rabbi Zippel in an interview. He referred to the Jewish Sabbath as a time where individuals disconnect themselves from all endeavors that enslave them throughout the week and compared the day to pressing a reset button on a machine. A welcome prayer over wine or grape juice from the men and candle lighting from the women invokes the Jewish Sabbath on Friday at sundown.

- ↑ "Strassburg, Robert". Milken Archive of Jewish Music. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Milken Archive of Jewish Music – People – Samuel Adler". Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 261.

- ↑ Since it is this meal that changes the other two from meals of a two-per-day nature to two of a trio

- ↑ Ein Yaakov: The Ethical and Inspirational Teachings of the Talmud. 1999. ISBN 1461628245.

- ↑ Derived from Isaiah 58:13–14.

- ↑ Mishnah Tractate Shabbat 7:2

- ↑ Chagigah 1:8.

- ↑ Klein, Miriam (April 27, 2011). "Sabbath Offers Serenity in a Fast-Paced World". Triblocal. Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ See Yosef Dov Soloveitchik's "Beis HaLevi" commentary on parasha Ki Tissa for further elaboration regarding the legal ramifications.

- ↑ Lubrich, Battegay, Naomi, Caspar (2018). Jewish Switzerland: 50 Objects Tell Their Stories. Basel: Christoph Merian. pp. 202–205. ISBN 978-3856168476.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Neulander, Arthur (1950). "The Use of Electricity on the Sabbath". Proceedings of the Rabbinical Assembly. 14: 165–171.

- ↑ Adler, Morris; Agus, Jacob; Friedman, Theodore (1950). "Responsum on the Sabbath". Proceedings of the Rabbinical Assembly. 14: 112–137.

- ↑ Klein, Isaac. A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice. The Jewish Theological Seminary of America: New York, 1979.

- ↑ Hannah Dreyfus (October 2, 2014). "New Shabbos App Creates Uproar Among Orthodox Circles". The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ↑ David Shamah (October 2, 2014). "App lets Jewish kids text on Sabbath – and stay in the fold; The 'Shabbos App' is generating controversy in the Jewish community – and a monumental on-line discussion of Jewish law". The Times of Israel. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ↑ Daniel Koren (October 2, 2014). "Finally, Now You Can Text on Saturdays Thanks to New 'Shabbos App'". Shalom Life. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Will the Shabbos App Change Jewish Life, Raise Rabbinic Ire, or Both?". Jewish Business News. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ↑ 8 saved during "Shabbat from hell" Archived 2010-01-19 at the Wayback Machine (January 17, 2010) in Israel 21c Innovation News Service Retrieved 2010–01–18

- ↑ ZAKA rescue mission to Haiti 'proudly desecrating Shabbat' Religious rescue team holds Shabbat prayer with members of international missions in Port au-Prince. Retrieved 2010–01–22

- ↑ Levy, Amit (17 January 2010). "ZAKA mission to Haiti 'proudly desecrating Shabbat'". Ynetnews. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Faigin, Daniel P. (2003-09-04). "Soc.Culture.Jewish Newsgroups Frequently Asked Questions and Answers". Usenet. p. 18.4.7. Archived from the original on 2006-02-22. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- ↑ "The Sunday-Sabbath Movement in American Reform Judaism: Strategy or Evolution" (PDF). AmericanJewishArchives.org. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Birnbaum, Philip (1975). "Sabbath". A Book of Jewish Concepts. New York, New York: Hebrew Publishing Company. pp. 579–581. ISBN 088482876X.

- ↑ "Judaism - The Sabbath". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ↑ Shulkhan Arukh, Orach Chaim 280:1

- ↑ "Sabbat Observance". AB Institute for Samaritan Studies, supported by the Israeli Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ↑ "Dying Out: The Last Of The Samaritan Tribe – Full Documentary". Little Dot Studios. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ↑ The Seven-Day Week.

- ↑ "Sabbath's Consistent Lunar Month Dates". 4 February 2015. Retrieved Dec 27, 2021.

the sacred seventh-day Sabbaths are forever fixed to the count from one New Moon to the next, causing them to consistently fall upon the 8th, 15th, 22nd, and 29th lunar calendar dates.

- ↑ Keyser, John D. "Biblical Proof for the Lunar Sabbath" (PDF).

- ↑ Cipriani, Roshan (Oct 1, 2015). Lunar Sabbath: The Seventy-Two Lunar Sabbaths: Sabbath Observance By The Phases Of The Moon. Scotts Valley, California: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1517080372.

- ↑ "tefilla – No Mekadesh Yisrael on Shabbat". Mi Yodeya. Retrieved 2022-06-22.