Ernest Hemingway House | |

Hemingway House in Key West, Florida | |

Interactive map showing the Hemingway House's location | |

| Location | 907 Whitehead Street Key West, Florida |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 24°33′04″N 81°48′02″W / 24.55119°N 81.80060°W |

| Built | 1851[1] |

| NRHP reference No. | 68000023 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 24, 1968[2] |

| Designated NHL | November 24, 1968[3] |

The Ernest Hemingway House was the residence of American writer Ernest Hemingway in the 1930s. The house is situated on the island of Key West, Florida. It is at 907 Whitehead Street, across from the Key West Lighthouse, close to the southern coast of the island. Due to its association with Hemingway, the property is the most popular tourist attraction in Key West. It is also famous for its large population of so-called Hemingway cats, many of which are polydactyl.

The residence was constructed in 1851 in a French Colonial style by a wealthy marine architect and salvager Asa Tift. From 1931 to 1939, the house was inhabited by Hemingway and his wife Pauline Pfeiffer. They restored the decaying property and made several additions. During his time at the home, Hemingway wrote some of his best-received works, including the non-fiction work Green Hills of Africa (1935), the 1936 short stories "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber", and the novels To Have and Have Not (1937) and Islands in the Stream (1970).[note 1] After the Hemingway's divorce and deaths, the house was auctioned off and subsequently converted into a private museum in 1964. On November 24, 1968, it was designated a National Historic Landmark.[3]

History

Early history

Construction on the house began in 1848 and was completed in 1851[5] by Asa Tift, a marine architect and salvage wrecker, in a French Colonial estate style.[6] The house's site, across the street from the Key West Lighthouse,[7] has an elevation of 16 feet (4.9 m) above sea level, making it the second-highest site on the island.[6][8] In addition to the elevation, the house's 18-inch thick limestone walls protect it during tropical storms and hurricanes.[9]

Hemingway

In 1928, writer Ernest Hemingway and his wife Pauline Pfeiffer moved to Key West, where they spent the next three years living in rented housing, the last being a two-story home at 1301 Whitehead Street.[10]

When Pauline had first seen 907 Whitehead Street during a house-scouting tour, she labeled it a "damned haunted house".[11] At the time, the house was in foreclosure and was in deep disrepair.[6] However, after recognizing its potential, she convinced her wealthy Uncle Gus to purchase it at $8,000 for her and Ernest as a wedding present.[12][13] Ernest appreciated the seclusion that the 1.5-acre lot would offer him while writing his works.[13] Employing out-of-work Conchs, the Hemingways restored the entire house.[14] Most of the house's inner furnishings were selected by Pauline, but Ernest insisted on the inclusion of his hunting trophies.[15] At the cost of air circulation, Pauline replaced the house's ceiling fans with chandeliers.[16] The couple also converted the second story of the carriage house into a writing studio for Ernest and transformed the basement into a wine cellar.[14]

While Hemingway was reporting in Spain in 1937, Pauline installed a large pool on the grounds.[17] The first swimming pool in the Florida Keys, the 24 x 60-foot[18] 80,000 US gal (300,000 L; 67,000 imp gal) pool was immensely expensive. At $20,000, it was two and a half times the purchase price of the entire property.[17][19] Upon his return, Hemingway was irate at the costly addition. With a melodramatic flourish, he threw a penny from his pocket onto the ground, declaring, "You might as well take my last cent," despite the fact that Pauline had paid for it herself. She kept the penny and later had it embedded in the concrete.[17] Despite his initial rage, the pool grew on Hemingway, and he later had a 6 feet (1.8 m) brick wall erected around the property so that he could swim nude.[18][20] Hemingway also kept peacocks on the property and organized boxing matches on the lawn.[21]

While living at the house, Hemingway wrote some of his best-received work, including the 1935 non-fiction work Green Hills of Africa, the 1936 short stories "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber", and his 1937 novel To Have and Have Not. After his death, a manuscript was discovered in a vault in the garage; this work was published posthumously in 1970 as Islands in the Stream.[6] After eight years of residing at the house, Hemingway moved to Cuba in 1939.[22]

Following their 1940 divorce, Pauline lived in the house until her death in 1951 and the house remained vacant afterward. The ownership of the house remained in Hemingway's name until his suicide in July 1961. Later that year, his three children auctioned off the house for $80,000.[6][23][24]

Modern museum

The new owners intended to use the Hemingway House as a private residence. However, due to persistent interest from visitors, they opened the house to the public as a museum in 1964. Although Hemingway's family had taken away much of the furnishings, the owners still possessed the bulkier furniture and many of Hemingway's possessions.[18] As a result of not all furniture being original, the authenticity of the museum has received some criticism.[12] All of the house's rooms are open to visitors, except for Hemingway's writing room, which can only be viewed through a screen.[16] The property is the most popular tourist attraction in Key West.[25]

Before Hurricane Irma struck the Keys in September 2017, the entire population of the island chain was ordered to evacuate by the federal government, but the museum's curator, general manager, and a team of employees declined to leave the house or evacuate its cats. Hemingway's granddaughter also urged them to evacuate, saying, "It's just a house." Instead, several employees chose to stay with the cats and the house. They survived the storm intact.[26][27]

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent decline in tourism, the museum laid off over 30 employees, half of their staff.[28][29]

Cats

The house and its grounds are inhabited by dozens of cats, commonly called Hemingway cats.[23] Around half are polydactyl, sporting six toes on each paw.[30] The cats bear the names of celebrities, such as Humphrey Bogart or Marilyn Monroe, and have their own cemetery in the house's garden.[23]

Legend has it that all cats on the property are descended from Snow White, a white six-toed cat[note 2] given as a gift to the Hemingways by a sea captain.[23][30] However, Hemingway's niece, Hilary, and his son, Patrick, have both contested the claim that Hemingway owned cats in Key West. A neighbor allegedly owned several polydactyl cats and some, such as Hilary, have suggested that these are the forebears of the Hemingway cats. Adding to the confusion, a photograph exists of a young Patrick and Gloria (Hemingway's daughter) playing with a white cat in Key West. When asked about the image, Patrick said he could not remember the incident.[31]

Beginning in 2003, the museum was embroiled in a nine-year legal struggle against the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) over whether the Animal Welfare Act of 1966, which typically regulates zoos and circuses with big cats, applied to the museum's six-toed feline population.[23] The USDA argued that the Hemingway House was essentially a zoo, with the cats functioning as an exhibit.[30] The USDA even sent undercover agents to monitor the cats in 2005 and 2006. The museum owners contested the USDA's claims in court. When an investigator for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) examined the cats in 2005, they concluded: "What I found was a bunch of fat, happy and relaxed cats." Ultimately, in 2012, the United States Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit ruled that the Animal Welfare Act was applicable because the museum used cats in advertisements and sold cat-themed merchandise.[23][32]

Gallery

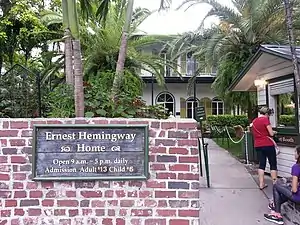

Entrance to the property

Entrance to the property A miniature house for the cats

A miniature house for the cats A cat lies on the porch

A cat lies on the porch Garden

Garden Ernest Hemingway House Historic American Buildings Survey plaque

Ernest Hemingway House Historic American Buildings Survey plaque Ernest Hemingway House National Historic Landmark plaque

Ernest Hemingway House National Historic Landmark plaque

The cat cemetery

The cat cemetery.jpg.webp) The house's veranda

The house's veranda Hemingway's pool

Hemingway's pool

See also

Notes and references

Notes

Works cited

- Brennen, Carlene Fredericka; Hemingway, Hilary (2015). Hemingway's Cats. Florida: Pineapple Press. ISBN 9781561646487.

- McIver, Stuart B. (2002). Hemingway's Key West. Florida: Pineapple Press. ISBN 9781561642410.

References

- ↑ "The House". The Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ↑ "National Register of Historical Places – Florida (FL), Monroe County". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. February 12, 2007.

- 1 2 "Hemingway, Ernest, House". National Historic Landmarks Program. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ↑ Ricks, Christopher (October 8, 1970). "At Sea with Ernest Hemingway". The New York Times. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ Chorney, Saryn (September 11, 2017). "All of Ernest Hemingway House's 54 Famous, Six-Toed Cats Accounted for After Hurricane Irma Batters the Florida Keys". People. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fogwell, Susan (December 3, 2014). "The Hemingway House in Key West". HuffPost. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ Miller, Mark (2008). Miami and the Keys. National Geographic Society. p. 225. ISBN 9781426203237.

- ↑ Alvarado, Francisco (September 6, 2017). "Home to Hemingway and lazy days, Key West girds for Hurricane Irma's wrath". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ Dangremond, Sam (September 11, 2017). "Ernest Hemingway's Key West Cats Made It Through Hurricane Irma Unscathed". Town & Country Magazine. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ McLendon, James (1990). Papa: Hemingway in Key West. Key West, Fla.: Langley Press. pp. 57, 130. ISBN 0911607072. LCCN 88081528.

- ↑ McIver (2002), p. 17.

- 1 2 Moddelmog, Debra A.; del Gizzo, Suzanne (2013). Ernest Hemingway in Context. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9781107010550.

- 1 2 McIver (2002), p. 18.

- 1 2 McIver (2002), p. 19.

- ↑ McIver (2002), p. 21.

- 1 2 "Polydactyl Cats". Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure. PBS. Archived from the original on May 7, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- 1 2 3 McIver (2002), pp. 21-22.

- 1 2 3 "Hemingway House Becomes a Museum". The New York Times. February 2, 1964. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ Gibson, Andrew (May 13, 2015). "Hemingway's legacy alive and well in Key West". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ Reynolds, Michael (1997). Hemingway: The 1930s. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. p. 268. ISBN 0393343200. OCLC 35397885.

- ↑ "Sun and Sloppy Joe's". Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure. PBS. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ↑ O'Connor, John (October 2, 2015). "Places Where Hemingway Lived or Traveled". The New York Times. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Alvarez, Lizette (December 22, 2012). "Cats at Hemingway Museum Draw Tourists, and a Legal Battle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 4, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ McIver (2002), p. 108.

- ↑ McIver (2002), p. 85.

- ↑ Astor, Maggie (September 11, 2017). "Hemingway's Six-Toed Cats Ride Out Hurricane Irma in Key West". The New York Times. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ↑ Schaub, Michael (September 11, 2017). "Hemingway's house and cats spared by Hurricane Irma". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ Miles, Mandy. "Key West's Iconic Hemingway House Lays Off 30+ Workers". Keys Weekly. Key West, Florida. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ Filosa, Gwen (August 29, 2020). "'It's sad.' Key West's Hemingway museum cuts half its staff, citing a decline in tourism". Miami Herald. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Bell, Maya (August 13, 2006). "Hemingway's cats have gone to court". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ Brennen & Hemingway (2015), Ch. 9.

- ↑ Khouri, Andrew (December 23, 2012). "Hemingway's famous cats still under government control, court says". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

External links

- Official website

- "Writings of Ernest Hemingway", broadcast from the Ernest Hemingway House from C-SPAN's American Writers

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. FL-179, "Tift-Hemingway House, 907 Whitehead Street, Key West, Monroe County, FL", 12 photos, 7 measured drawings, 9 data pages, 1 photo caption page, supplemental material