| Endothiodon Temporal range: Wuchiapingian, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of specimen AMNH 5618 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia |

| Family: | †Endothiodontidae |

| Genus: | †Endothiodon |

| Type species | |

| †Endothiodon bathystoma Owen, 1876 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

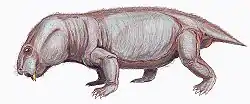

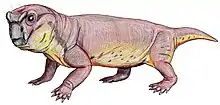

Endothiodon (/ɛndoʊθiːoʊdɔːn/ "inner tooth" from Greek endothi (ἔνδοθῐ), "within", and odon (ὀδών), "tooth", most likely named for the characteristic of the teeth being placed internally to the maxilla[1]) is an extinct genus of large dicynodont from the Late Permian. Like other dicynodonts, Endothiodon was an herbivore, but it lacked the two tusks that characterized most other dicynodonts. The anterior portion of the upper and lower jaw are curved upward, creating a distinct beak that is thought to have allowed them to be specialized grazers.[2]

Endothiodon was widespread and is found across the southern region of what was then a single large continent known as Pangea. It was originally only found in southern Africa but has now also been found in India and Brazil, which were both close to Africa at the time. The finding in Brazil marks the first dicynodont to be reported for the Permian of South America.[1] This finding also shows that part of the Rio do Rasto Formation in Brazil can now be correlated with deposits in India, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.[1]

Originally there were thought to be nine species, but this was reduced down to just 3 species.[3] A fourth species was later discovered. The four currently known species of Endothiodon are E. bathystoma, E. uniseries, E. whaitsi, and E. mahalanobsi. However, the basic distinction among the four species is size, which leads some to believe that E. uniseries, E. bathystoma, and E. whaitsi may actually represent an ontogenetic series rather than three distinct taxa.[1] E. mahalanobsi, on the other hand, is most likely a separate, truly smaller species based on the size of both juvenile and adult forms that have been found. Apart from size, E. mahalanobsi also has a single longitudinal ridge on the snout (compared to three on the other species), a lower position of the pineal boss, and a swollen prefrontal bone.[1]

Description

Skull

The skull of Endothiodon is most quickly recognized by the prominent upturned beak. The premaxilla and palate of the upper jaw are vaulted and allows for the upturned and pointed lower jaw to fit into this region.[3] On the lower jaw, lateral to the teeth, is a broad groove. Endothiodon lacks a lateral dentary shelf but has a bulbous swelling of the dentary. The function of this swelling is not yet known. The pineal foramen is situated on a boss, which is high in three of the species and low in one of them (E. mahalanobsi). There is also a boss situated on the ventral margin of the jugal.[1] The anteroventral process is an anteroposteriorly short triangular bone, while in most other dicynodonts it is long and pointed.[4]

Teeth

The teeth in the upper and lower jaw differ both in morphology as well as in tooth replacement.[2] The teeth of the upper jaw tend to be larger (5–9 millimetres (0.20–0.35 in)) than those of the lower jaw (<5 millimetres (0.20 in)) and are serrated on the anterior edge while the lower jaw has serrations on the posterior edge.[3] Although it was originally thought that E. bathystoma had several rows of teeth on the upper jaw, it was later discovered that the tips of the teeth from the lower jaw had been left behind in the upper jaw. Now it is known that the upper teeth are roughly positioned into a single row.[3] The entire row is moved posteriorly so that the anterior portion of the premaxilla contains no teeth but the most posterior portion still holds two teeth. The teeth are also situated internally to the edge of the maxilla.[3]

It was first thought that the dentary contained three parallel rows of teeth. Instead of arranging the teeth in longitudinal rows, they are now known to fall into obliquely arranged Zahnreihen.[2] In each Zahnreihe, the anteriormost tooth is the oldest and the posterior most tooth is the youngest. There is active ongoing replacement of these tooth rows. The distal portion of each tooth is compressed from side to side and is somewhat pear shaped in cross section.[3]

The palate shows two distinct regions that are covered in minute foramina. These areas probably had a horny covering in life. The broad groove running along the tooth row on the dentary was probably also covered by a horny layer.[2] It is possible that these regions allowed for occlusion where the upper teeth met the groove lateral to the lower teeth and the lower teeth met one of the regions of the palatine.[3] This is still under scrutiny as the palatine region is short in comparison to the lower tooth row and the second horn covered area on the palatine does not oppose any structure in the lower jaw.[3] Because the palatine region is shortened, effective occlusion for shearing would only be possible when the lower jaw was in a retracted position.[5]

History of discovery

)_(18161883181).jpg.webp)

Endothiodon was first discovered by Richard Owen in 1876 in the Karoo region of Beaufort Group, South Africa based on a skull and mandible. The genus was described based on the anterior portion of a snout and the corresponding part of the dentary, creating an upturned beak.[6] Several more specimens have since been collected, many of them in the Beaufort Group in South Africa, it is here that the first partial skeleton was discovered by Broom in 1915.[3] In the 1970s a skull and lower jaw was discovered in Brazil. The specimen was originally assigned to the genus Endothiodon. Boos later reexamined the specimen and confirmed this assignment which marked Endothiodon as the first Permian dicynodont to be found in South America.[1]

Four main endothiodont genera, Endothiodon, Esoterodon, Endogomphodon, and Emydochampsa, were originally separated under the subfamily Endothiodontinae. When E. uniseries was first discovered it was thought to be the type species of the genus Esoterodon.[7] In 1964 Cox sorted out all of the taxa of endothiodonts and found that the characters originally separating the four genera were not valid. The four genera were grouped into the one genus Endothiodon.[3] With originally nine species of Endothiodon, Cox was able to narrow it down to just three species based on skull size and robustness of the lower jaw.[3] A fourth species of Endothiodon was found in India that was unique compared to the other three species. It had a small size, a single longitudinal ridge on the snout, an elongated pineal foramen situated on a low boss located midway on the intertemporal bar, and a slender dentary symphysis. Some of these characteristics such as the shape of the pineal foramen and the presence of three longitudinal ridges were thought to be distinguishing characteristics of the genera as a whole, but are now only valid at specific level.[5] Another new species was collected in Tanzania in 1963 and is under description. It is distinguished from all other specimens based on the lack of a pineal boss and the presence of a pair of tusks lateral to the tooth row.[1]

Phylogeny

The phylogenetic relationships of Endothiodon in a cladogram after Angielczyk & Rubidge (2010):[8]

| Dicynodontia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palaeobiology

Diet

In adult Endothiodons the lower jaw teeth are pear shaped in cross section, compressed distolaterally, and has posterior serrated edges while the upper jaw teeth have anterior serrated edges. In the juveniles, the lower jaw is a lot smaller and more slender. The lower jaw contains one functional tooth row with 5-6 teeth. The teeth are small, conical, and pointed. The distal edge contains serrations that are just starting to appear. The juvenile teeth are much simpler and are more similar to that of a carnivore than an herbivore. It is possible that the different tooth morphology might be due to a change in diet from insectivorous or omnivorous as a juvenile to herbivorous as an adult. This would be achieved as size increases and it is more able to adapt to being herbivorous.[5]

Palaeoecology

Endothiodon was first discovered in the Karoo region of Beaufort West, South Africa.[6] The Karoo region is characteristic of siltstones that are fine-to medium- or coarse-grained, dark or greenish grey, and very finely crossbedded.[9] Since then several more specimens have been found in African countries including the Usili, Ruhuhu and lower part of the Kawinga Formations of Tanzania, the basal beds of Madumabisa Mudstone of Zambia, and Chiweta Beds, Malawi.[10] Endothiodon has been placed in the Endothiodon[11] and/or Cistecephalus Assemblage Zones and dates back to a Late Permian (Tatarian) age.[10] In 1997 the first specimen of E. mahalanobsi was found in the Kundaram Formation in the north-western part of Pranhita-Godavari valley near Golet in Adilabad district, Andhra Pradesh, India.[5] The Kundaram Formation is characterized by mudstone, sandstone, and ferruginous shale.[5] In addition to Africa and India, Endothiodon is also known from the Morro Pelado Member of Rio do Rasto Formation in the Paraná Basin, Brazil.[1]

A taphonomic reconstruction of the Late Permian showed that there were well established, dense, riverine vegetation.[12] It was originally thought that Endothiodon would grub matter out of the ground using its beak.[3] This is now seen as implausible because of the position of the external nares on the snout being placed so far anteriorly. Instead, it is now thought that Endothiodon inhabited the dense riverine vegetation and would crop foliage with its beak before processing it with its specialized and extensive oral cavity.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Boos A. S., Schultz C. L., Vega C. S., Aumond J. J. (July 2013). "On the presence of the Late Permian dicynodont Endothiodon in Brazil". Palaeontology. 56 (4). doi:10.1111/pala.12020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Latimer E. M., Gow C. E., Rubidge B. S. "Dentition and feeding niche of Endothiodon (Synapsida;Anomodontia)" Palaeontologia Africana 32, 75-82 (1995)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Cox Barry C. "On the palate, dentition, and classification of the fossil reptile Endothiodon and related genera" American Museum of Natural History 2171 (1964)

- ↑ Modesto Sean P., Rubidge B. S., Welman J. "A new dicynodont therapsid from the lowermost Beaufort Group, Upper Permian of South Africa" Canadian Journal of earth Sciences 30: 1755-1765 (2002)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ray Sanghamitra "Endothiodont dicynodont from the Late Permian Kundaram formation, India" Paleontology 42:2, 375-404 (2000)

- 1 2 Owen R. "Descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the fossil reptilia of South Africa in the collections of the British Museum" Taylor and Francis (1876)

- ↑ Seeley H. G. "Researches on the structure, organisation, and classification of the fossil reptilia. Part IX. Section 1. On the therosuchia. (Abstract)" The Royal Society 55, 224-226 (1894)

- ↑ Kenneth D. Angielczyk; Bruce S. Rubidge (2010). "A new pylaecephalid dicynodont (Therapsida, Anomodontia) from the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone, Karoo Basin, Middle Permian of South Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (5): 1396–1409. Bibcode:2010JVPal..30.1396A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.501447. S2CID 129846697.

- ↑ Verniers J., Jourdan P. P., Paulis R. V., Frasca-Spada L., De Bock F. R. "The Karroo Graben of Metangula Northern Mozambique" Journal of African Earth Sciences 9:1, 137-158 (1989)

- 1 2 Ray Sanghamitra "Permian reptilian fauna from the Kundaram Formation, Pranhita-Godavari Valley, India" Journal of African earth Sciences 29:1, 211-218 (1999)

- ↑ M.O. Day, R.M.H. Smith (June 2020). "Biostratigraphy of the Endothiodon Assemblage Zone (Beaufort Group, Karoo Supergroup), South Africa". South African Journal of Geology. 123 (2): 165-180. doi:10.25131/sajg.123.0011.

- ↑ Smith Roger M. H. "Vertebrate taphonomy of Later Permian floodplain deposits in the southwestern Karoo basin of South Africa" South African Museum 8, 45-67 (1993)